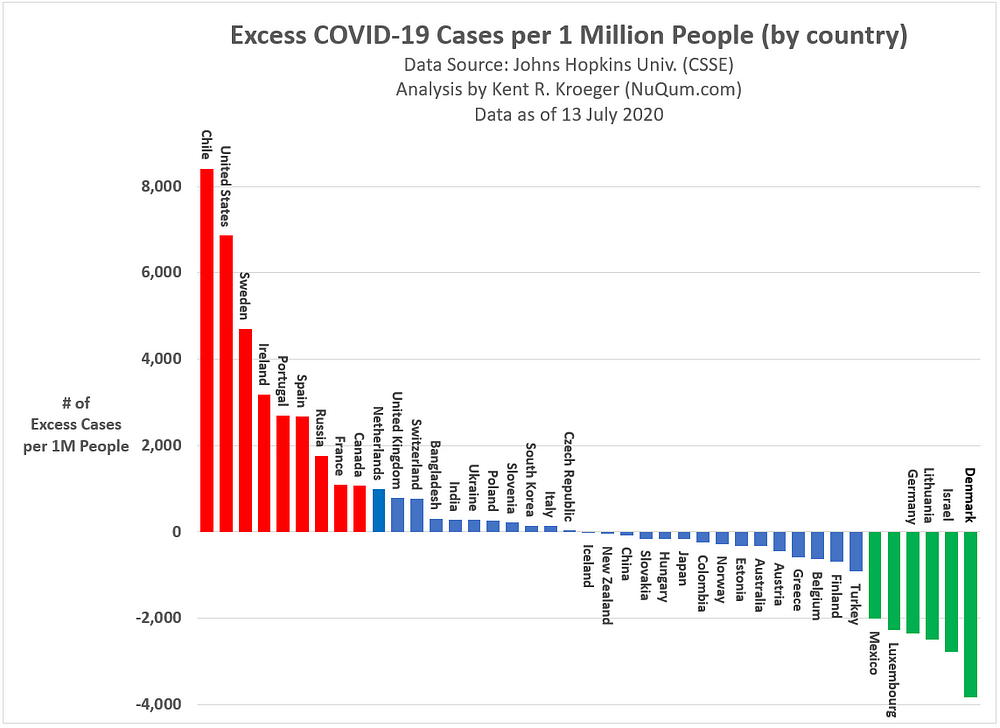

By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; July 30, 2020)

OK, British actor Henry Cavill, star of Netflix’s The Witcher, didn’t actually break the internet–an overused and lazy description for digital content that spreads rapidly and organically through various social media platforms.

Examples of such content include music videos (Who can purge Rebecca Black’s “Friday” from their memory bank?–a YouTube video with over 144 million views), social commentary videos (My favorite being an ad agency-produced video titled “10 Hours of Walking in NYC as a Woman” that has garnered over 49 million views since being posted in 2014–more impressively, it has attracted over 270 response videos, generating over 147 million additional views ), and plain quirky videos–one of the most famous being “Star Wars Kid” which has enjoyed a modest 35 million views since its posting in 2006 and has inspired dozens of imitator and parody videos.

In Cavill’s case, a July 16th Instagram video of him building a gaming PC has already attracted over 4.7 million views in under two weeks.

And the original Cavill-produced video has inspired dozens (by now, maybe hundreds) of reaction videos–more aptly described as videos of people watching Cavill building a PC, the most popular of which are each closing in on one million views.

Cavill, by his own multiple admissions, is a serious PC-gamer and was a fan of the PC-game version of The Witcher well before getting the lead role in its TV incarnation. However, he is not the first celebrity to self-produce a gaming PC build video. Actor Terry Crews regularly receives one million plus YouTube views for his videos regarding his PC-gaming obsession and his own gaming PC build.

According to a few serious PC-gamers I know through my teenage son, Crews and Cavill are the authentic deal. Just watch Cavill’s PC-build video, particularly when he gently locks the CPU into place with a thin metal lever (at the 0:44 mark in the original video)–he’s clearly done this before.

But Cavill’s PC-build video takes the genre to an additional level through its synergy with Cavill’s professional life.

If you don’t know who Henry Cavill is, here is a quick recap: He’s the best movie Superman since Christopher Reeve and might be the best had he been given decent scripts and directing (though Batman V Superman: Dawn of Justice is grossly underrated).

More recently, Cavill has taken on another superhero-ish character in Geralt of Rivia, a product of sorcery who becomes a monster-hunter known as a “witcher.” Set in a medieval-inspired fantasy world called “The Continent.” The Witcher was created by Polish writer Andrzej Sapkowski, but its story is best known through its PC-gaming spin-off (now in its third version).

My teenage son says the role-playing, PC-version of The Witcher is for gaming “hardcores,” but as for the TV version–which, given its contextual similarities, receives frequent comparisons to HBO’s Game of Thrones (GOT)–it is a different beast entirely from GOT or other fantasy epics.

For one, The Witcher‘s narrative is reducible to a simple dramatic arc as it focuses on its lead character–Geralt–and the two most important women in his life: a young woman linked to his destiny (Ciri) and a rather fetching sorceress (Yennefer) who regularly appears and reappears in Geralt’s life.

The Witcher is less complex than GOT and not as Homeric in its ambitions. Equating the two shows is like saying Rawhide and Gunsmoke were essentially the same TV show (I just dated myself).

I am not a fan of high fantasy literature, having only read in my lifetime a handful of books from series like J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire [a.k.a. Game of Thrones], and Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea. As such, this essay does not intend to sell anyone on (or against) The Witcher TV series or its literary source material.

For what it is worth, after binge-watching all eight of The Witcher‘s Netflix episodes, I found the blizzard of unfamiliar proper nouns along with the dense intricacy of the show’s many plot threads to be a touch overwhelming—only coming together in the last three episodes when the background stories for Geralt, Ciri and Yennefer finally converge. Season 2 appears well-positioned to benefit from the groundwork laid in Season 1.

My purpose here is not to do a TV review; but, instead, bring attention to the The Witcher‘s unlikely success story and how Cavill—playing the show’s central protagonist—has perhaps revealed the template for how sci-fi/fantasy franchises (not named Marvel) can still thrive in an entertainment industry seemingly determined to kill the genre.

While The Witcher thrives with viewers, other sci-fi franchises are suffering

By industry standards, one season alone cannot establish The Witcher as an unqualified success. But the show has much to be proud of in its short history. For example, according to Parrot Analytics, a media demand measurement company, The Witcher‘s US debut on December 20, 2019 was the third most-in-demand streaming series ever measured–behind Stranger Things and The Mandalorian. In just a week after its debut, The Witcher was the most-in-demand streaming series in the world, dethroning Disney’s The Mandalorian.

In January, 2020, Netflix announced that The Witcher‘s audience in the first season, and after only one month of availability, exceeded 76 million viewers. With eyeball-popping numbers like that, Netflix didn’t require any verbal gymnastics to trumpet The Witcher‘s initial audience success.

Compare that to how the mainstream entertainment media covered the ratings for the September 2017 debut of CBS All-Access streaming series, Star Trek: Discovery.

From Variety’s Janko Roettgers “exclusive” report on the Star Trek: Discovery’s ratings debut:

CBS was able to almost double the mobile subscription revenue for its CBS All Access service with the premiere of “Star Trek: Discovery,” according to new data that app analytics specialist App Annie exclusively shared with Variety this week. Additionally, the number of downloads of the CBS mobile app grew by 2.5x following the premiere of the show.

CBS premiered “Star Trek: Discovery” both on broadcast TV as well as on its subscription streaming service CBS All Access on September 24. The first episode was free to watch for everyone; episode number two, which premiered on the same day, has only been available to CBS All Access subscribers.

To sweeten the deal, CBS has been giving All Access subscribers a 7-day free trial period. This means that anyone who signed up on September 24, and decided to stick around, saw their credit card charged on October 1. That day, the CBS app on iOS and Android did indeed see a revenue hike of 1.8x, compared to the average in-app revenue during the previous 30 days.

This is how an audience ratings story is written when the real numbers are disappointing and the entertainment reporter is little more than a propaganda mouthpiece for large media corporations.

A more useful number for Star Trek: Discovery—particularly if comparing it to The Witcher—came from Nielsen Media Research, who reported that Discovery‘s first episode was watched by 9.5 million viewers. Rick Porter, a well-known TV ratings reporter, described Discovery‘s debut ratings as “decent.” He was being kind.

There is no reason to pick on Star Trek: Discovery, however. The number of sci-fi/fantasy franchises that have died (or are dying fast) grows with each new ratings period:

- HBO cancelled its critically-acclaimed “Watchmen” series (26 Emmy nominations) after just one season (9 episodes) due to less-than-great audience numbers.

- DC Comics’ 2020 “Birds of Prey” movie, an intended launchpad for Margot Robbie’s Harley Quinn character, died a quick box office death.

- Warner Brothers’ Supergirl TV series has seen its average season viewership over five seasons drop from 9.81 million (Season 1) to 1.58 million (Season 5).

- And in case you thought this is just a rant against female-led sci-fi/fantasy shows, Fox’s Seth McFarland-led The Orville has seen its viewership decline from 8.56 million in its first episode (Sept. 2017) to 2.97 million in its most recent episode (April 2019).

The audience problem for the sci-fi/fantasy genre is bigger than partisan politics.

My favorite sci-fi franchise, the BBC’s Doctor Who, has hit a ratings low since its reboot in 2005. According to Doctor Who TV, the premiere episode under current showrunner Chris Chibnall and “Doctor” (Jodi Whitaker) in 2018 attracted 10.96 viewers. Two complete seasons later, their most recent episode reached 4.69 viewers. Subsequently, what would be only the second time in the show’s history, there is a real chance the iconic BBC franchise will be cancelled after next season.

But not even the decline of Star Trek and Doctor Who can equal the heartbreak of watching the demise of modern science fiction’s most celebrated franchise, Star Wars, under Disney’s ownership.

Following the critical disaster of last year’s The Rise of Skywalker, unverified rumors have emerged that Disney is considering the creative cop-out of declaring the Disney trilogy movies (The Force Awakens, The Last Jedi, and The Rise of Skywalker) as part of an alternative universe distinct from the original trilogy—which is little more than the last words of a dying patient. Its J. J. Abrams’ Kelvin timeline for Star Trek all over again, only with cuter droids. Should the alternative universe angle be pursued by Disney, it will fail to save Star Wars, just like Abrams killed the lucrative Star Trek movie franchise.

Apart from the Marvel superhero movie franchise, the end of science fiction and fantasy in mainstream entertainment today is nearly complete.

But I don’t blame Marvel for this decline (though its enormous popularity has probably sucked some of oxygen away from other sci-fi franchises).

I don’t blame video games (though my anecdotal experience with my teenage son and his friends supports the hypothesis that fantasy-based video games are far more stimulating and rewarding than TV shows or movies).

I don’t blame the soul-grinding negativity of today’s science fiction writers either (though I dare anyone to watch two consecutive episodes of Star Trek: Picard without needing to pop a couple Xanax tablets).

And I don’t even blame Hollywood’s “wokeness” or political correctness (though it has encouraged a tsunami of IQ-draining, political message scripts that read more like bad middle school history lectures than thought-provoking drama—I’m talking to you Chris Chibnall).

Nothing better highlights Hollywood’s self-important, imperious tendency than the recent words of CBS Star Trek‘s executive producer Alex Kurtzman during 2020’s virtual Comic-Con as he promoted the #StarTrekUnited hashtag on Twitter:

“Star Trek, really since its inception, has always endeavored to speak to the vision where everybody really is united and a lot of the differences dividing us these days are gone,” said Kurtzman during CBS’s virtual Star Trek panel. “It’s unfortunately not the vision that the rest of the world is living in (today). #StarTrekUnited is is an effort to bring awareness to many of the organizations that are critical right now such as Black Lives Matter and the NAACP.”

Apparently, Alex Kurtzman’s has the authority to speak for the conditions in the “rest of the world.” Kurtzman’s co-executive produce, Heather Kadin, isn’t humble either:

“We are proud to be working on a show that has a message that really matters,” added Kadin, executive producer of CBS’s upcoming animated show, Star Trek: Prodigy. “I think anyone on this side of the camera (or) on the other side of the camera is hoping to say something. What’s great is you often get to say things about current events and mask them so they don’t feel like medicine or that you’re being taught something; in the case of Star Trek, thematically, it’s been baked into what Star Trek is about: a better hope about equality, gender equality, racial equality, and sexual equality.”

That is one way to describe CBS’s treatment of the Star Trek franchise. Actual Star Trek fans offer a different take:

“They are using Star Trek to push their own personal (f-ing) political views,” responds Tom Connors, a lifelong Star Trek fan and producer of the Midnight’s Edge podcast on YouTube.

As if we don’t get enough politics in our daily lives already, Hollywood routinely now forces overt political agendas into their movies and TV shows. I call it Hollywood’s anti-entertainment strategy. Most of it is mind-numbingly unpleasant to consume—watch 15-minutes of any Star Trek: Picard episode and you will think the Alpha Quadrant in the 24th century is dominated by Donald Trump’s offspring.

In particular, CBS’ Picard is unsparingly dark and depressing–and never play a drinking game where you take a straight whisky shot after every murder during an episode. By the end, you will be floor-crawling drunk.

As any fan of the original Star Trek will tell you, part of the show’s attraction was the intrinsic nature of its progressive, anti-bigotry principles (though a few of its episodes in the last season fell a bit short in that regard).

In the episode, The Ultimate Computer, from the original Star Trek’s second season, the character Dr. Richard Daystrom (played by William Marshall), considered one of the most brilliants minds in the Federation, designs and tests a supercomputer called the M-5 Multitronic System, a revolutionary tactical and control computer engineered to do the work of hundreds of Enterprise crew members. Through the entire episode, there is no mention that Dr. Daystrom is a Black man as it was irrelevant to the plot.

When Captain Kirk’s court martial in Season 1’s 20th episode is presided over by Commodore Stone, a flag officer to Kirk’s line officer status, the character is played by Canadian actor Percy Rodriguez—who is of African-Portuguese descent.

In Season 1’s 16th episode–The Galileo Seven–Spock commands an expedition party that gets stuck on an uncharted planet populated by giants, only to lose two crew members as they try to escape. The most interesting dramatic element in that episode is the interaction between Spock, the Enterprises’ senior science officer and second-in-command, and astrophysicist Lieutenant Boma, played by Don Marshall, an African-American actor. As Spock made a series of “rational” but unpopular decisions during their ordeal, it was Lt. Boma (along with Doctor McCoy) who dared to challenge Spock’s strict logical governance style.

Marshall would say many years later about Star Trek, “if you look at Star Trek you have every nationality in the book on the show. That’s opening the door to saying ‘the only reason the world is surviving is because we pull together.'” As for his one-episode role as Lt. Boma, Marshall was grateful to the episode’s scriptwriters—Oliver Crawford and

S. Bar-David—for not making his ethnicity a relevant part of the story.

The matter-of-factness of diversity on the original Star Trek was one of its enduring strengths.

So why is The Witcher succeeding where others are failing?

Its hard to say sci-fi/fantasy franchises are failing when, in 2019 worldwide movie grosses alone, the genre took in over 8 billion dollars. But take out Marvel superhero and Star Wars movies and the numbers become more modest.

In fact, despite their box office prowess, there are many reasons to worry about the future of the Marvel and Star Wars franchises too. Both have likely experienced the crest of their creative high points. That The Mandalorian is the best thing LucasFilm and Disney Star Wars has in production right now is evidence of this problem. At some point Buck Rogers (the biggest sci-fi property of its time) had to hang up his jet pack, and so too will The Force have to fade into the past.

It is going to be new franchises, such as The Witcher, that are going to carry the sci-fi/fantasy torch into the future–which is why Cavill’s gaming PC build video is far more important than just its ability to garner a few million YouTube views.

Knowingly or not, Cavill is giving Hollywood free lessons on how to build a lucrative new sci-fi/fantasy franchise. He gave his first lesson last year while promoting The Witcher premiere.

When baited by a media reporter to give his opinion about the negative impact “toxic fans” on well-established franchises such as Star Wars and Star Trek, Cavill’s answer shut the reporter down as easily as Superman stops bullets.

“When it comes to fans, it is a fan’s right to have whatever opinion they want to have, and people are going to be upset… I don’t necessarily consider that toxic. I just consider that passion,” said Cavill.

In this simple statement, Cavill establishes that genre or franchise fans are not the problem–and, quite the opposite, they are the safety net for franchises that may need time to build a stable, lucrative audience.

Cavill’s First Lesson for Hollywood: ‘Toxic fans’ is another term for ‘core audience.’

Hollywood may think they gain their progressive bona fides by shunning these fans, but they are actually turning away the core audience who would otherwise show up at theaters in the first week of release and watch the TV show premieres and buy the board games.

The corporate suits running the current sci-fi/fantasy franchises are cutting their audiences in half under the false pretense that they are building new audiences.

But Cavill’s next lesson for Hollywood may be more important.

Franchise spin-offs have a potential ‘core audience,’ but that doesn’t mean these fans will show up anytime that franchise has a new movie or TV show. The core audience needs to trust the creative forces behind any spin-off.

In The Witcher’s case, it had a passionate fan base before the Netflix series ever premiered. In book sales alone, The Witcher series has sold over 50 million copies worldwide. Add to that over 28 million copies of the PC game, The Witcher 3, and it is not hard to understand why a media company might want to create a TV series around it.

Which is where Cavill’s gamer PC build video establishes his second and most important lesson.

Cavill’s Second Lesson for Hollywood: By respecting the ‘core audience,’ you have a better chance of adding new audiences

Social media is an ugly, mean place. And when you start navigating within its subgroups, such as the sci-fi and gaming communities, it can get even uglier. Phonies are easily spotted and quickly mocked (and then shunned).

After watching a dozen or so serious PC experts on YouTube critique Cavill’s PC building skills–he was generally praised for his hardware selections and widely commended for

What has been fascinating are the number of my family and friends who know Cavill as Superman, but have never read The Witcher books, don’t care about fantasy literature in general, and never play PC games, but had to tell me about Cavill’s PC build video. And it wouldn’t surprise me if half of them at least sample The Witcher on Netflix in the near future.

Anecdotal evidence it may be, but consistent with everything I’ve seen and read about audience building: the importance of word-of-mouth and trusted opinion leaders, which can lead to sampling, which can lead to a loyal customer (viewer). A company’s core customers are often their best salespeople.

But when a studio alienates its core audience? Well, you get ratings declines like those seen for Doctor Who and other science fiction franchises.

Henry Cavill and Netflix’s The Witcher prove it doesn’t have to be that way.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: kroeger98@yahoo.com or tweet me at: @KRobertKroeger1