By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, August 28, 2017)

{ Feel free to send any comments about this essay to: kkroeger@nuqum.com or kentkroeger3@gmail.com}

The Washington Post’s Ed Rogers just declared that “the Democratic candidates appear to be coalescing around a core set of issues that constitute a dangerous lurch to the left.”

Why?

According to Rogers, “Any Democrat who wants to be taken seriously must support a single payer health care system, a $15 minimum wage, free college tuition, affirmative support for sanctuary cities along with minimal immigration controls and, finally, a contender must completely embrace Black Lives Matter.”

While the surface evidence supporting Rogers’ argument is strong, the exact opposite process may be underway within the Democratic Party.

Democrats may someday look back at the last week of August 2017 as the start of their party’s neutering of its Bernie Sanders-wing.

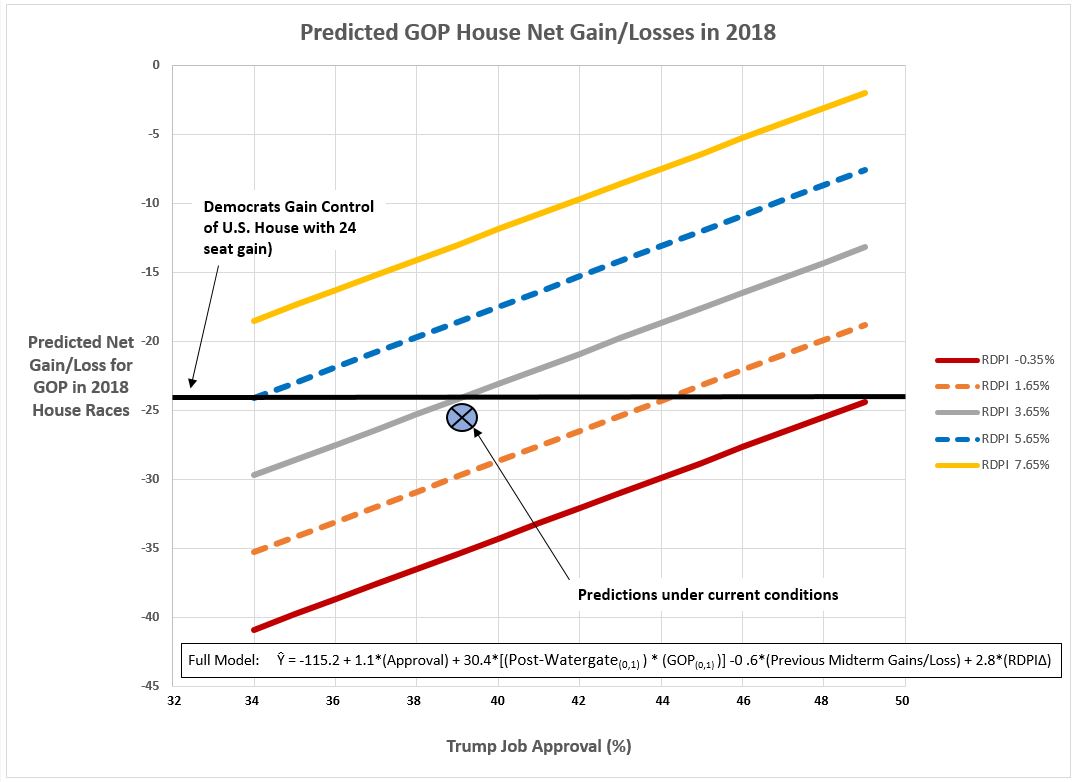

OK, that’s a bit of hyperbole, but there were two recent events that hint at some complex strategic thinking occurring within the Democratic Party’s leadership. After months of being little more than the “anti-Trump”-party, the Democrats recognize that the far left elements of their party must be exorcised now or risk losing an opportunity in 2018 and 2020 to take back the U.S. House and presidency, respectively.

The first strategic move was a simple and obvious one to take.

On August 29th, House minority leader Nancy Pelosi issued a statement condemning Antifa , a radical leftist, loosely organized political movement that tolerates violence (if necessary) against “fascist” opponents they target.

“Our democracy has no room for inciting violence or endangering the public, no matter the ideology of those who commit such acts,” read her statement. “The violent actions of people calling themselves Antifa in Berkeley this weekend deserve unequivocal condemnation, and the perpetrators should be arrested and prosecuted.”

While the condemnation came a little late for some, the statement was evidence that the Democratic Party’s leadership finally understands the blow back risk posed by Antifa’s violent actions at protest rallies across the nation.

When President Trump made his now infamous “many sides” comment regarding the violence at the Charlottesville “Unite the Right” march, the justifiable effort of Democratic leaders to stake out the high ground would have been much easier had Antifa counter-protesters not bashed in the heads of a few neo-nazis and white supremacists, thereby making it easier for the conservative media to suggest the propensities for violence were equivalent on both sides.

Speaking to the Denver Posts’ editorial board, Pelosi said, “You’re not talking about the far left of the Democratic Party — they’re not even Democrats. A lot of them are socialists or anarchists or whatever.”

As political tactics go, Pelosi’s harsh statements regarding Antifa carry little risk. Nonetheless, as one of the party’s most senior leaders, her rebuke carries significant weight among other Democratic elites.

Time will tell if the Democratic leadership can effectively separate themselves from the violent elements in their ranks that have been energized by the often over-heated, hyperbolic rhetoric coming from congressional Democrats such as Maxine Waters, Adam Schiff and Nancy Pelosi herself.

Will Single Payer Health Care Finally See Its Day in the U.S.?

The more significant and complex strategic move by the establishment Democrats occurred in Oakland, California later in the week.

During a town hall meeting on August 30th, California Senator Kamala Harris endorsed Senator Bernie Sanders’ proposal to expand the federal Medicare program to all Americans. Sanders intends to introduce the single payer health care bill (often called “Medicare for All”) sometime in September.

“I intend to co-sponsor the ‘Medicare for All’ bill because it’s just the right thing to do,” Harris said during the town hall. “It’s not just about what is morally and ethically right, it also makes sense just from a fiscal standpoint.”

The last sentence is a textbook Clintonian tactical move. Blunt criticism from your left flank by endorsing their holy grail issue — universal health care — but leaving the door open to ultimately reject any specific plan to convert the American health care to a “Medicare-for-All” (MFA) or other type of universal heath care system.

That’s a pretty cynical interpretation of what sounded like a genuine endorsement of the MFA idea by Harris, isn’t it?

Yes, it is — but not without cause.

First, congressional observers do not expect the bill to become law — at least not anytime soon — which makes any support for it now a relatively empty gesture. Three years is an eternity in politics and policy stands taken today can easily be shifted (and even reversed) should events warrant, particularly for a candidate relatively new in the public eye.

Hillary Clinton was too well-known in 2008 and 2016 to be allowed the policy latitude required of a successful presidential candidate. Harris will not have that problem.

Second, while Harris has spoken favorably about MFA in the past, it was always in very general terms and she was never a leader in California’s own effort to implement MFA at the state-level.

This underscores what has been one of the key features of Harris’ young political career, first as a district attorney and later as the state’s Attorney-General: She is a pragmatist more inclined to negotiate deals with vested interests and stakeholders surrounding an issue than to take a strong ideological stand.

The best example of this Harris characteristic is found in how she addressed foreclosure fraud in California at the beginning of this decade. As she likes to reminds us, Harris took California out of the nationwide mortgage settlement talks in 2011 on the grounds that they were too generous to the banks. Instead, she had California negotiate its own deal — partly in response to her biggest political competitor, lieutenant governor Gavin Newsom, calling for such a move.

When the left speaks, Harris listens. That’s not a criticism. It’s often a smart move.

In the end, however, while getting banks to pay over $20 billion in debt relief and financial assistance, the California deal was still criticized by advocacy groups that noted banks themselves would pay only around $5 billion which amounted to between $1,500 and $2,000 of direct debt relief to individual homeowners.

In other words, banks felt little pain from the California deal even as the Democratic Party’s establishment immediately promoted Harris as someone tough on banks and a champion of hard-working families.

“Harris’s actions on the issue in many ways serve as a microcosm of her broader political agenda,” wrote Branko Marcetic for Jacobin Magazine. ” The foreclosure deal, while an impressive and landmark settlement, was also a half-measure that delivered far less to the public than it seems at first glance, ultimately failing to properly take the banks to task for their criminality.

The third reason we should be skeptical of Harris’ endorsement of MFA is also her most distinctive feature since emerging on the national stage. She is the Democratic Party’s best fundraiser not named Bernie. Moreover, she has received formal introductions to and received substantial donations from the crown jewels of the Obama and (Bill and Hillary) Clinton donor base.

Harris’ headliner appearance in the Hamptons for a July 2017 fundraiser hosted by Michael Kempner, a top donor and bundler in the past for Obama, Hillary Clinton, and the Democratic Party, proved to be a hit among some of the Democratic Party’s most important kingmakers. Kempner called her a “star” and Kendall Glazer, granddaughter of billionaire Malcolm Glazer, the late owner of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers football team and the Manchester United soccer team, offered equally effusive praise for the junior California senator.

Why should her ability to raise money among the Democratic Party’s wealthiest donors prove she won’t be faithful in her endorsement of Sander’s universal coverage bill?

It doesn’t — but recent experience suggests healthcare and insurance money matters a lot. When a quarter of this nation’s most prominent healthcare executives, such as Independence Blue Cross CEO Daniel Hilferty, threw their support behind Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump in 2016, it surprised few political observers when Hillary declared at a 2016 Iowa caucus event that a single payer system “will never, ever come to pass.”

In fairness, Hillary was more about defending Obamacare at the time than disparaging the single payer concept, but it nonetheless suggested her corer belief — and that of the Democratic establishment — was that the vested interests arrayed against a single payer system were too strong.

An MFA, single payer system will, for all practical purposes, put the private health insurance industry, with over $480 billion dollars in 2015 revenues , out of business. If you think the 859 health insurance companies in the U.S. will let that happen without a major fight, you would be wrong. Furthermore, i don’t see any indication in Harris’ history that she has the inclination or stomach to take on that industry.

In the “Not News” Category: The Democratic Party Remains Deeply Divided

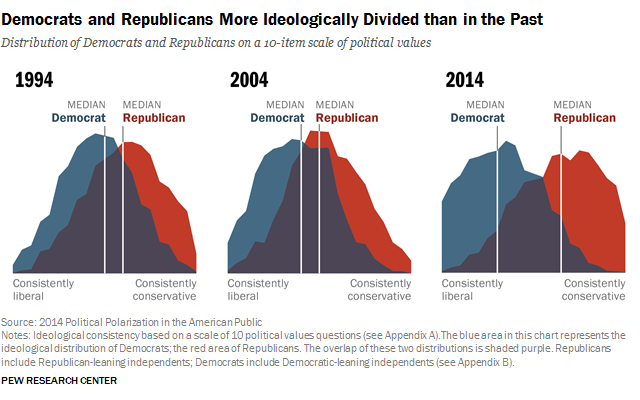

The health care debate within the Democratic Party is driven by its two major leadership factions — the “establishment wing” and the “progressive wing.”

Now, almost a year removed from the 2016 election, these two factions are still not getting along, despite a common belief between them that — at some level — the two sides must reach a truce of some sort. A divided Democratic Party puts at risk the party’s likely gains in the 2018 and 2020 elections.

A Short History of the Democratic Party since 1985

The Democratic Party’s establishment wing, still dominated by associates of the Clintons and Obama, traces its modern origins to the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC), founded in the wake of Walter Mondale’s landslide defeat to Ronald Reagan in 1984. The DLC and its affiliated think tank, the Progressive Policy Institute (PPI), mapped an electoral strategy in the mid-1980s that would lead to the election of two two-term Democratic presidents.

The DLC and PPI’s central premise was that, since the 1960s, the Democratic Party had moved too far to the left and had become viewed by average Americans as anti-business and out-of-touch with average American’s economic concerns. Recognizing the joint interests of average Americans, the public sector and corporate America was, in part, the DLC’s co-opting of the Republican brand that Reagan had employed so successfully (less government, deregulation, free markets). By moving corporate interests back into the Democratic Party mainstream, the major issue differentiator between the two parties would become social and identify issues.

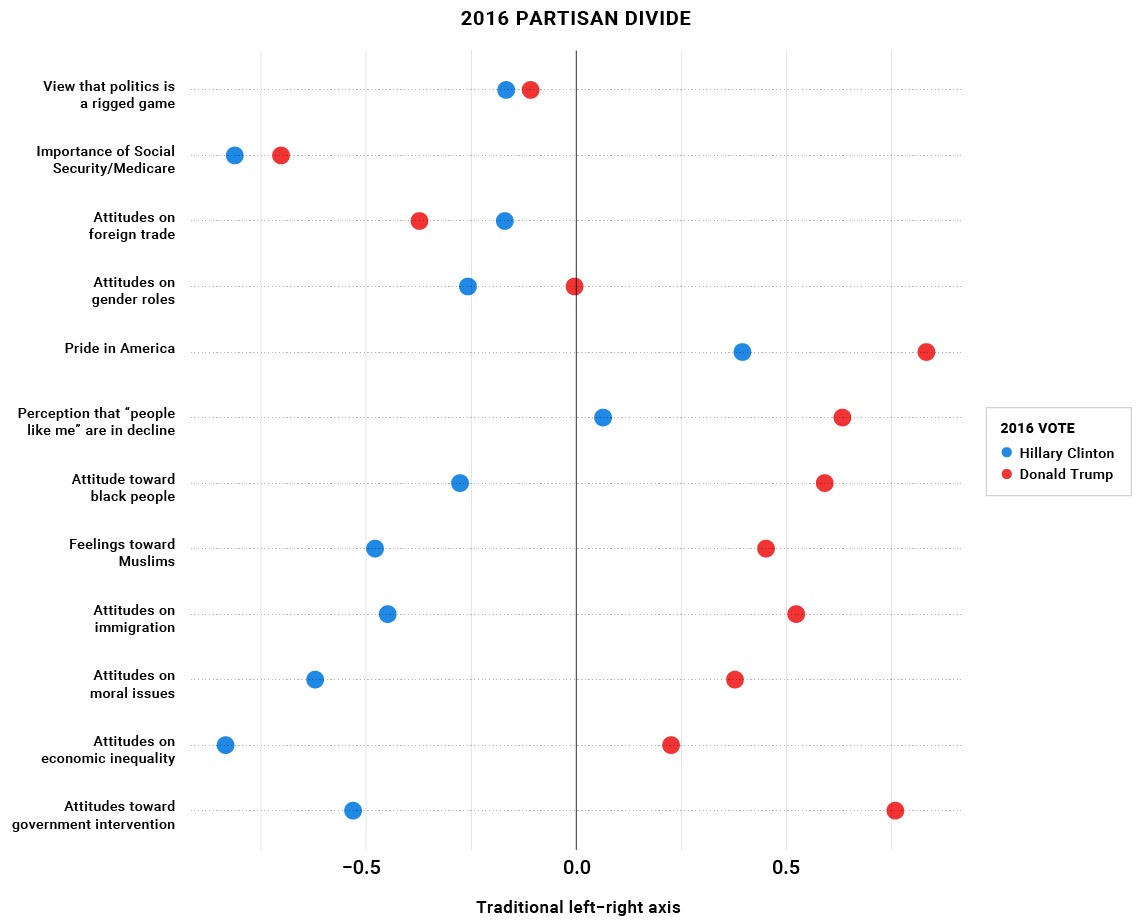

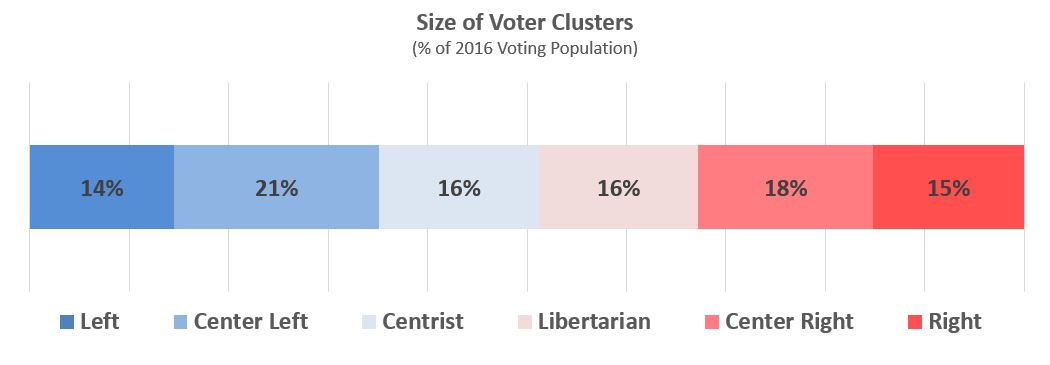

Lee Drutman, from the Democracy Fund’s Voter Study Group, provides a nice graphical visualization of how the DLC project still defines how American voters divided themselves up in the 2016 election.

The Clintonian-vision of free markets and liberal social ideals had been the Democrats’ whyfor through the Obama administration.

And then came Bernie Sanders — the progressive left’s cranky uncle that has never been welcomed in the Democratic family (by his own choosing) but around whom a large, frustrated and disenfranchised segment of the Democratic rank-and-file quickly embraced.

The Clinton project and its Obama modification (which shed the post-911 neocon foreign policy creep increasingly exhibited by the party’s professorate class) brought prosperity for one-quarter of Americans, left half treading water, and the rest as a persistent underclass. That this underclass, over-represented by racial and ethnic minorities, would always be a reliable Democratic voter bloc was assumed.

The 2016 Election Marks the End of the Clintonian Dominance of the Democratic Party — or is it?

As the 2016 general election drew to a close, many political observers were sounding the alarm that the Democratic Party was repelling white, working-class voters in droves. It didn’t help that the most influential book behind the Obama 2008, 2012 and Clinton 2016 campaign strategies, John B. Judis and Ruy Teixeira’s, The Emerging Democratic Majority, all but concluded that the white, working-class Philistines still hanging around the party’s electoral margins would not be necessary to elect Democrats in the not-so-far future.

A perfectly fine strategy if the Democrats have no interest in winning elections between the Cascade and Appalachian mountains. Winning back control of the U.S. House with mostly coastal congressional seats leaves the Democratic Party with little margin of error. Electoral competitiveness in middle America gives the Democrats some breathing room but requires their winning a healthy share of white, working-class voters.

Yet, even after the Clinton 2016 debacle, many on the intellectual left continue their call for the permanent excommunication of white, working-class whites from the Democratic coalition. Instead, they return to the emerging Democratic majority thesis and say the Democrat’s growing demographic advantage requires only that the party turns out its core voters to win elections.

“Turnout isn’t everything; it is the only thing.” exhorts essayist Dan McGee. “If every Democrat who votes will vote Democrat, then the easy way for Democrats to win is to ensure that many Democrats vote.”

Before putting on her eye creme, Kellyanne Conway prays each night that the Democrats continue to follow McGee’s advice.

Will Public Opinion Determine if Single Payer Actually Happens?

In an August 2017 Quinnipiac Poll of 1,125 registered voters, 51 percent of respondents supported replacing the current health care system with a single payer system in which Medicare covers every American citizen. Only 38 percent opposed such a change.

That is a big gap, but big enough to warrant mainstream Democrats embracing a single payer system?

While encouraging for single payer supporters, public opinion-level support for universal health care is not sufficient to judge the wisdom of Harris’ decision to support Sanders’ single payer plan.

This country has never fought a presidential election with universal health care as its central issue. As political scientists will tell you, elections shape public opinion as much as their results are driven by public opinion.

The relationship between public opinion and election outcomes is non-recursive — causation flows in both directions. For example, elections shape public opinion when they educate voters about the parties’ relative issue stances and help voters align their own stances with their preferred party or candidate. That is why using survey results from the 2016 election to make strategic decisions about the 2018 and 2020 elections can be misleading. New candidates and issues can fundamentally change the electoral dynamics in the next election.

However, sometimes shit happens and exogenous shocks to the system (e.g., 2008 financial crisis, hurricanes, terrorist attacks, Comey letters, etc.) force politicians to react to real changes in public opinion and mood.

As of today, we don’t know if health care will be a prominent issue in 2020 — and, if it is, in what context does it attain this importance?

The Republicans are Prepared to Fight a Single Payer System

The health sector accounts for 18 percent of the American economy, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Before Congress hands it over to the public sector, here are just a few of the arguments we can expect to hear from the Republicans:

- It will lead to health care rationing (of course, the Democratic reply is that we already have health care rationing)

- It will empower an already bloated federal government

- It will restrict patients’ freedom of choice

- It will deliver inferior health care services

- The burden of financing a single payer system will fall on the middle class

- And, ultimately, will cost more than the current system

Whether there are strong counter arguments to the Republicans is not the only consideration for Democrats. The Republican 40-year project of cultivating the federal government as oppressive and incompetent-narrative has never been effectively countered by the Democrats. At least not on a consistent basis.

Bill Clinton tacitly accepted the Reagan argument as he deregulated the economy and turned the federal government into an enabler of the private sector’s best and worst instincts. Still, the federal government never shrank in real terms as much as it did during the Clinton presidency (thanks largely to the post-Soviet peace dividend).

Elected on the heals of the country’s worst economic recession since the Great Depression, Obama tried to re-energize the concept of government-centered problem solving, but ultimately failed under a well-coordinated barrage of Republican propaganda and a wall of congressional intransigence.

It doesn’t help Democrats’ government-centered proposals that much of the public’s real-life contacts with the government tend to end up as negative experiences (DMV, IRS, etc.). Yes, the military generally gets high marks from the public, but the Republicans have always been shrewd in keeping the military separate from their criticisms of the federal government.

So, if this country is going to move to a single payer health care system, the barriers will be enormous. Hillary was cynical but right about Bernie’s single payer proposal. Under current conditions, it will never pass even a Republican-controlled Congress.

A universal health care system in the U.S. is, at a minimum, 5 to 10 years away.

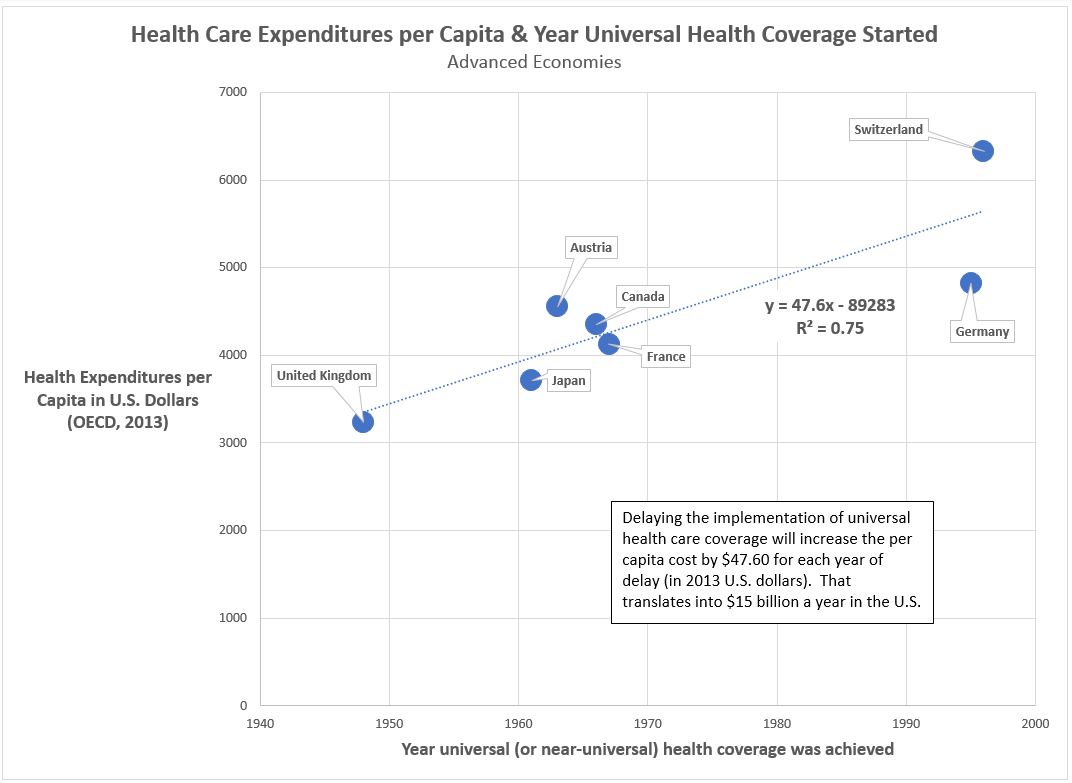

NuQum.com’s analysis of universal health care systems in seven other advanced economies shows that there is a potential cost in delaying the adoption of a universal health care system (see chart below) — perhaps as much as a $15 billion-a-year additional increase in health care expenditures for every year the U.S. delays in adopting a universal health care system.

The earliest adopters of a universal health care system — United Kingdom and Japan — have the lowest health expenditures per capita. In contrast, late-adopters like Germany and Switzerland have higher per capita expenditures.

This relationship could be the result of late-adopting countries having inherently more expensive health care systems, thereby making the conversion to a universal health care system more difficult (Germany and Switzerland both have federal political systems — as does the U.S., of course). On the other hand, the higher per capita costs for late-adopters could be a function of vested interests (insurance companies, physicians, pharmaceutical companies, etc.) having had more time to solidify their power over the country’s health care system.

Either way, if the U.S. is to join the above chart, it will start in the upper-right-hand corner (late adopter / high per capita expenditures) as the most costly health care system in the world ($8,713 per capita health care expenditures in 2013 dollars). Sadly, the high cost of the U.S. health care system translates into only average health care outcomes and lifespans for its citizens.

You would think that fact alone would inspire our politicians to seriously consider a single payer / universal health care system, and perhaps it is this fact that explains Harris’ conversion to the idea. But, I believe otherwise.

Harris’ Endorsement of Medicare-for-All More Likely a Tactical Chess Move

Harris’ endorsement of the Sanders health care plan is most likely a shrewd move to blunt the threat of a Sanders candidacy in 2020 (or the candidacy of a similar Democratic progressive).

Three years removed from the 2020 elections, now is the time for the Democratic establishment to dampen the progressive wing’s energy sources. They don’t need to sap all of its energy, just enough to avoid the party division seen in 2016. Harris needs to win the 2020 Iowa Caucus by 5 percentage points, not Clinton’s 2016 margin of 0.1 percentage points.

Expect over the next few months more and more establishment Democrats endorsing, conceptually, ideas such as free public college tuition, a minimum wage hike, student debt forgiveness, support for sanctuary cities, amnesty, and Medicare-for-All.

There is little cost in taking these positions now, particularly among Democratic candidates that are relatively new on the scene (Harris, Gillibrand. Opinion shifts are more likely to be forgiven coming from Harris than a more established politician such as Elizabeth Warren or Joe Biden.

As Harris said when endorsing Sanders’ plan, MFA makes sense from a “fiscal standpoint.” But when the details of the Sanders plan become apparent, so will the associated costs. That event will offer Harris (and the Democratic establishment) the cover to say, “We didn’t sign up for that — and neither will the American people.”

Politics is a strategic game with many players and many possible moves. In Harris announcing her support for the Sanders health care plan, we are seeing just the first moves in a very long and complicated political game leading up the 2020 election.

About the author: Kent Kroeger is a writer and statistical consultant with over 30 -years experience measuring and analyzing public opinion for public and private sector clients. He also spent ten years working for the U.S. Department of Defense’s Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness and the Defense Intelligence Agency. He holds a B.S. degree in Journalism/Political Science from The University of Iowa, and an M.A. in Quantitative Methods from Columbia University (New York, NY). He lives in Ewing, New Jersey with his wife and son.