By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; July 26, 2022)

Regardless of what we hear today in the national news media, the potential for voter fraud has been and remains a critical issue in U.S. elections, even though past U.S. elections have not experienced widespread voter fraud (including the 2020 presidential election).

One reason for this is that leaders in both the Republican and Democratic parties, at least before 2020, generally agree that protecting the integrity of the voting process is vital to election legitimacy. And efforts to ensure that legitimacy identify absentee voting as one of the weakest links in the voting process.

To illustrate, during a North Carolina voting commission meeting in 2018, the state’s Attorney General, Josh Stein, a Democrat, said “the bulk of voter fraud is by absentee.”

At the time, that was not a controversial statement. Academic research and investigative journalism on vote fraud has frequently found absentee voting is vulnerable to fraud (examples here, here, here, here and here). A North Carolina congressional race would have been stolen by the Republicans in 2018 through ballot harvesting fraud had not one of their operatives, the recently deceased McCrae Dowless, been particularly careless in paying campaigns workers to collect absentee ballots (a crime in North Carolina) and, in some cases, filling out incomplete ballots (also a crime).

Before the toxic partisanship of today’s political environment, a 2005 bipartisan study on the health of the U.S. electoral system, chaired by former President Jimmy Carter and former Secretary of State James Baker, concluded:

“Absentee balloting is vulnerable to abuse in several ways: Blank ballots mailed to the wrong address or to large residential buildings might get intercepted. Citizens who vote at home, at nursing homes, at the workplace, or in church are more susceptible to pressure, overt and subtle, or to intimidation. Voting buying schemes are far more difficult to detect when citizens vote by mail. States therefore should reduce the risks of fraud and abuse in absentee voting by prohibiting “third-party” organizations, candidates, and political party activists from handling absentee ballots.”

The Commission on Federal Election Reform (CFER) concluded that “absentee ballots remain the largest source of potential voter fraud,” and proposed mitigating the risks of absentee balloting — which the Commission considered a necessary component of an electoral system designed to maximize voter participation — by limiting those who can handle a voter’s ballot to:

- the voter,

- a family member,

- the U.S. Postal Service (or legitimate shipper of U.S. mail),

- and election officials.

As of May 2022, 25 states allow some form of “ballot harvesting” where a third-party, approved by the voter, can deliver a completed ballot to election officials. Within those 25 states, laws vary on who qualifies to vote absentee, on who may not deliver completed ballots, and on the number of ballots that designated third-parties can deliver.

Sadly, on the issue of absentee voting and third-party ballot handling, the recommendations of the CFER have gone largely ignored.

And here we persist, today, in the shadow of a 2020 election that was unique in many ways, not the least of which was the percentage of votes cast through absentee ballots due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Why do some people remain convinced there was widespread voter fraud in the 2020 election?

I have not seen any proof of systemic vote fraud in the 2020 election, but some people believe it did exist — often citing very sketchy evidence.

Case in point: Dinesh D’Souza’s documentary film, 2000 Mules. While provocative and worth viewing, the film was only a first step in what should have been a more thorough and scientific investigation. Instead, the film’s most important conclusions were almost entirely predicated on odd coincidences, not irrefutable proof.

Can we conclude that there was election fraud if people who delivered absentee ballots at drop-off boxes are known — through geolocation data from cellphones — to have passed by those drop-off boxes multiple times over the course of the election? No, we cannot.

Coincidence, while it can prompt more thorough scientific investigations into important questions about reality, cannot be offered as final proof of anything. If there is one thing statistics has taught me, it is that life is full of coincidences that provide no substantive information for explaining the world.

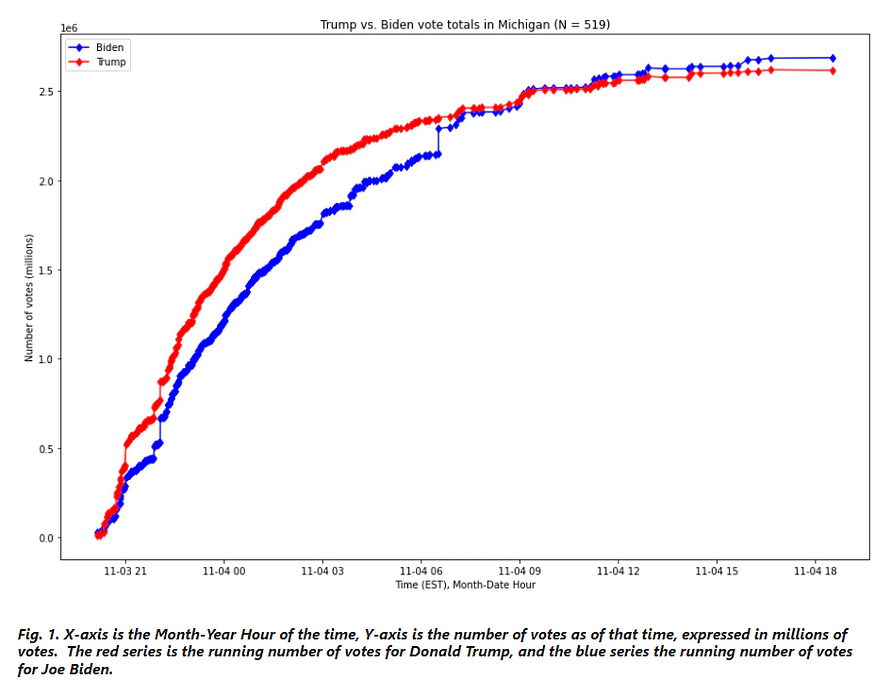

Yet, if I were a Donald Trump partisan, the coincidences from the 2020 election as portrayed in the graphics in Figures 1 and 2 below — generated from New York Times public-access voting data — would launch me into low-Earth orbit.

Figure 1: Cumulative 2020 Presidential vote results by day and time (Michigan)

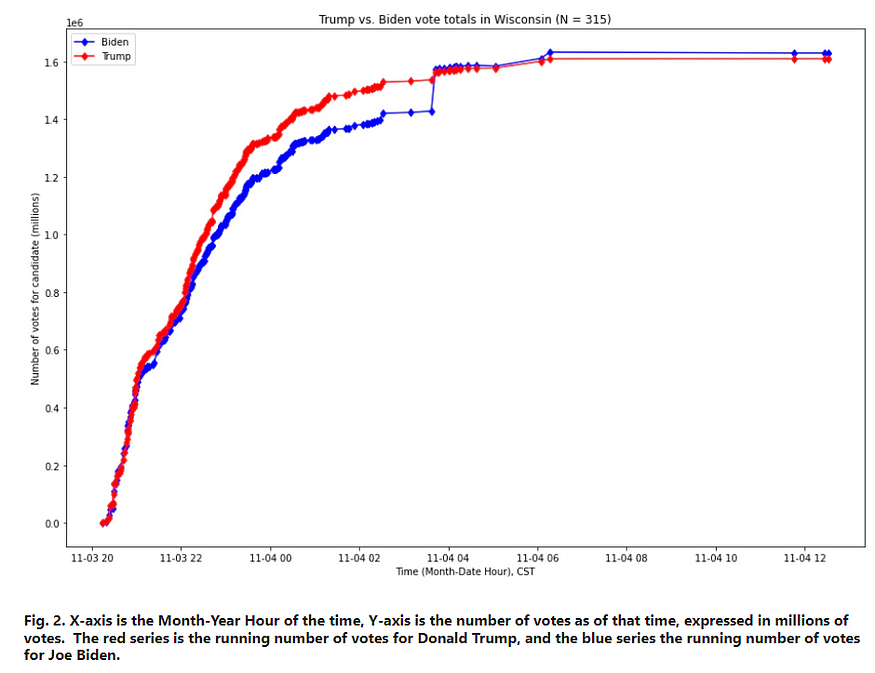

Figure 2: Cumulative 2020 Presidential vote results by day and time (Wisconsin)

Lumber back in time with me and imagine you are a Trump voter who goes to bed around midnight on election night believing (based on reported voting results) that Trump was comfortably ahead in Michigan and Wisconsin, only to find out the next morning he was behind and in a neck-to-neck battle with Joe Biden.

As we now know, those sudden spikes in the blue lines (Biden votes) in the wee-wee hours of November 4th were the result of absentee ballot counts in large, urban districts being reported in bulk (i.e., predominately Democratic voting areas).

Why couldn’t those absentee votes have been reported earlier? In some states, like Wisconsin, the law mandates absentee ballots cannot be counted before Election Day. But it is fair to ask why absentee ballots, such as in Wisconsin, cannot be included in vote totals on election night?

But this country has never had elections like 2020 in the past, which probably explains why so many people remain dubious of that election’s results. In previous elections, absentee ballots were a minor proportion of total vote totals and rarely were the deciding factor in election outcomes.

That all changed in 2020 — and for good reason, as we were in the midst of a global pandemic and the thought of masses of people converging on in-person voting locations seemed socially irresponsible.

The fact absentee balloting was so essential to the 2020 election is hard to second-guess. It was an unusual year, as was the election itself.

Still, as a natural cynic, I do wonder if this drastic alteration in traditional voting methods did, in fact, play a deciding role in the final outcome in 2020. The Democrats were uniquely positioned to exploit this change in voting mode.

This thought is not the same as saying, the 2020 results were the product of voter fraud. I have no reason to reject the absentee vote totals. To the contrary, I assume, with no contradictory evidence proving otherwise, that everyone that filled out an absentee ballot in 2020 were eligible voters who expressed their true vote preferences on those ballots. Furthermore, I also assume the election officials in all 50 states (plus the District of Columbia) employed state-of-the-art methods to ensure that every absentee voter was eligible and did not vote more than once.

At this juncture, I suspect readers are dividing into one of two groups: One group thinking, ‘Yeah, I believe the state’s have the capacity to ensure the validity of absentee ballots.’ And the other thinking, ‘There is no frickin’ way state election officials knew for certain that every absentee ballot was legitimate.’

Cautiously, I stand with the former group — state’s do, in fact, have validated database methods to ensure the legitimacy of absentee ballots. Was their due-diligence perfect in 2020? Probably not. But idiosyncratic failures in confirming absentee voting do not constitute a conspiracy to steal the 2020 election.

However, I understand why Trump voters feel absentee voting in 2020 distorted the final results.

It doesn’t take a conspiracy theorist to question the 2020 election results, it just takes strong partisanship and dose of human nature.

Vote Integrity, an analytic project headed by Matt Braynard, Trump’s former Campaign Director of Data and Strategy (so take its findings with the necessary caution), conducted an analysis of state-level 2020 presidential votes by the time of each vote update. Their analysis rendered the following conclusion:

This report studies 8,954 individual updates to the vote totals in all 50 states and finds that four individual updates — two of which were widely noticed on the internet, including by the President — are profoundly anomalous; they deviate from a pattern which is otherwise found in the vast majority of the remaining 8,950 vote updates. The findings presented by this report suggest that four vote count updates — which collectively were decisive in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Georgia, and thus decisive of a critical forty-two electoral votes — are especially anomalous and merit further investigation.

We further find that if these updates were only more extreme than 99 percent of all updates nationally in terms of their deviation from this generally-observed pattern, that, holding all else equal, Joe Biden may very well have lost the states of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Georgia, and that he would have 42 fewer Electoral votes — putting Biden below the number required to win the Presidency. Either way, it is indisputable that his margin of victory in these three states relies on four most anomalous vote updates identified by the metric developed in this report.

Contrary to Vote Integrity’s conclusions, it is not a mystery why Michigan, Wisconsin and Georgia had anomalous vote updates in 2020 — those were states identified as “battleground” states by both parties and where the Democrats employed the most aggressive absentee and vote harvesting methods, and where the Republicans put up aggressive resistance to those voting methods. (Note: Vote harvesting is where third-parties are allowed to handle completed ballots before they are delivered to election authorities)

Vote Integrity did not discover evidence of voter fraud — they discovered evidence that the Democrats were better prepared for the pandemic-driven changes in how people voted in 2020.

The 2020 presidential vote results in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Georgia represent the fact the Democrats possessed a far more sophisticated approach to absentee voting than the Republicans.

But in the midst of the Democrats’ superior vote collecting methods, could there still have been some nefarious activities that distorted the 2020 outcome?

One statistical test that might reveal that type of fraud is Benford’s law. The test’s rational is that in any large, randomly produced set of natural numbers, which some argue U.S. national and state elections follow, will find around 30 percent of those numbers will begin with the digit 1, 18 percent with 2, and so on, with the smallest percentage beginning with 9. A similar distribution exists for second digits.

A Benford’s law analysis of the 2020 presidential election found possible evidence of vote fraud in the county-level Pennsylvania vote. Wrote the study’s authors, Brooks Groharing and Dr. David McCune, “The argument that the failure of Biden’s county-level votes in Pennsylvania to follow Benford’s law is an indication of voter fraud is interesting and cannot be dismissed entirely.”

Yet, the authors concluded based on comparisons with previous presidential election data, “The (vote fraud) argument fails.”

Fair enough. Benford’s law is not the last word on vote fraud. But are U.S. elections immune from electoral chicanery?

Of course not.

Was it vote fraud or were the Democrats better positioned demographically in 2020?

I’m comfortable saying there was no concrete evidence of systematic vote fraud in the 2020 election — but I’m equally comfortable saying the rise of absentee voting, particularly allowing partisan third-parties to handle completed ballots, is a recipe for a future election disaster.

The statistical and forensic tools available to identify the some ways in which an absentee ballot can be corrupted (e.g., voter intimidation, ballots completed by someone other than the voter) are limited.

At a minimum, the rise of absentee voting has increased the number of election races where the results are not just untimely (i.e., outcome not known for days, or weeks, after Election Day), but has increased instances where vote totals have changed dramatically well after the close of

This type of election volatility breeds distrust in the election system and promotes concerns about vote fraud — and that is a problem that cannot be coldly brushed off as a ‘conspiracy theory.’ It is human nature and we cannot build and promote an electoral system that ignores our inherent frailties.

The popular assumption is that Republicans want to limit the electoral franchise through vote eligibility and mode restrictions — which disproportionately disadvantages non-white voters — while the Democrats aim to expand the franchise in opposition to such restrictions, thereby maximizing non-white vote turnout.

That assumption is mostly true, but it presupposes the false belief that the Democrats have an impenetrable advantage over Republicans in attracting non-white voters.

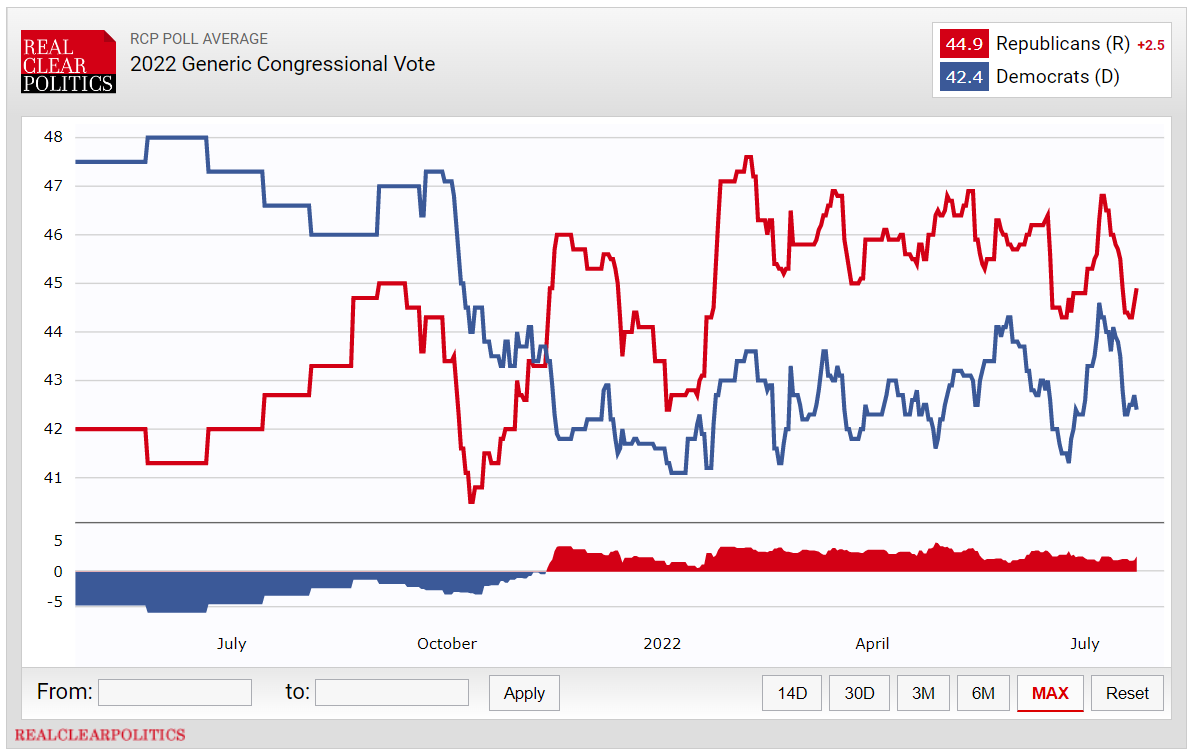

The opinion survey evidence suggests the Republicans remain competitive with the Democrats for congressional votes, despite the Supreme Court’s June 24th decision to overturn Roe v. Wade (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Generic congressional vote for 2022 (RealClearPolitics)

The news is also hopeful for the Republicans in attracting Hispanic voters — the country’s fastest growing voter bloc.

A small-sample New York Times-Siena College poll in July 2022 found that the vote intentions of Hispanics was equally divided between the two major parties (41% preferring Democrats versus 38% preferring Republicans).

Even with the fact that polling Hispanic voters remains a difficult task for U.S. pollsters, any assumption that non-voting Hispanics are guaranteed Democrat voters is dubious.

Biden won the 2020 presidential election, in part, because his party executed the most sophisticated vote harvesting methods in U.S. election history.

If the Republicans were to match the Democrats’ vote harvesting prowess in the future, it is reasonable to assume they would be more than competitive electorally going forward.

According to demographic data and exit polls, 45 million white Americans did not vote in 2020, compared to 16 million Hispanics, 11 million Blacks, 5 million Asians, and 4 million “other” races and ethnicities.

Assuming the Republicans can dominate vote preferences among white low-likelihood-voters similar to 2020 (56% vs. 34%) and are competitive among low-likelihood voters who are Hispanic, Asian or “Other,” they are certainly viable in future presidential elections. And if the GOP were to ever reach anything near 15 percent of the Black vote, future presidential elections likely will be dead-heats in the popular vote (My statistical analysis leading to this conclusion is available on GitHub).

My point is that the Democrats’ advantage in vote harvesting could be negated if the Republicans had any initiative to match the Democrats at that vote collection method. The 2020 gap in absentee ballot voting was substantially in Biden’s favor (65% for Biden versus 33% for Trump), with 46 percent of the vote being cast that way. For the GOP to win another presidential election, that gap must close.

Nonetheless, I am not advocating for the expanded use of vote harvesting and absentee voting, in general. To the contrary, it fundamentally violates the requirements of a strong electoral system (see Appendix for the attributes of a good electoral system) and increases the potential for systematic voter fraud — even if such fraud did not occur as some have claimed in the 2020 presidential election.

My stack of multiple absentee ballots mailed to me for the 2020 election stands as testament to one of that voting method’s most dangerous flaws.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to kroeger98@yahoo.com

Appendix: An Inventory of Election System Attributes

Building upon the conclusions of the Commission on Federal Election Reform (CFER), and incorporating research from scholars such John M. Carey, Gary Cox, Harry Eckstein, and Arend Lijphart, I created an inventory of key attributes that can be used to judge the health and effectiveness of a country’s electoral system.

The five attributes of an electoral system, including a letter grade (A to F) I collectively gave U.S. and state election laws on each attribute, are:

- Inclusiveness of franchise — Are there groups legally or effectively excluded from the vote franchise (e.g., felons)? Does partisan gerrymandering systematically diminish the importance/impact of some voters? (A-)

- Voting barriers—How easy is it to register to vote? Are there early voting and absentee voting options? (B+)

- Vote integrity — Are election results timely or prone to long delays? What rules govern an individual ballot’s chain of custody? Are vote tabulations independent of political bias? Are reliable processes in place to identify ineligible voters or tampered ballots? (C+)

- Relevant electoral choices — Do parties respond to voter preferences in the candidate selection process (e.g., primaries)? (Democrats = D- / GOP = B+)

- Policy responsiveness — Do elections matter in terms of the public policies implemented? (F)

Overall, I’d give the U.S. a gentleman’s C for the inclusiveness, integrity and effectiveness of its electoral system.

Hey, at least we beat Russia on this scale (who I give a solid F).