By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, May 25, 2021)

Unknown at the time, President Donald Trump’s prospects for re-election may have ended on June 20, 2019, when he unilaterally decided — against the wishes of his hawkish foreign policy and military advisors — to abort a planned retaliatory strike against Iran.

Revealing a side of Trump few in the news media acknowledged or believed to exist, the president cited his fear that Iranian civilians would be among the victims of an American airstrike against the Iranian military installations suspected to have been used a day earlier to shoot down a U.S. surveillance drone.

Trump told his stunned advisors, some already monitoring the military operation, that the contrast between the loss of one unmanned drone to the potential loss of dozens of Iranian civilians would be a public relations victory for Tehran, whereas the U.S. military gain would be minimal. Some mocked his scrubbing of the Iran attack as proof that the president was getting his foreign policy advice directly from Fox News’ Tucker Carlson, a persistent critic of the expected U.S. attack on Iran in the days leading up to Trump’s June 20th decision.

Never mind that Trump’s neocon-friendly Middle East policies —such as the exit from the Iran Nuclear Deal and the re-imposition of severe economic sanctions,— were the proximal causes of the June 2019 tensions between the U.S. and Iran, when the moment came to pull the trigger, the president (to his credit) stepped back.

Most prominent members of the GOP’s neocon-wing muted their public criticisms of Trump’s decision, including Liz Cheney (R-WY), who told conservative radio host Hugh Hewitt: “The failure to respond to this kind of direct provocation that we’ve seen now from the Iranians, in particular over the last several weeks, could in fact be a very serious mistake.”

Privately, the failure of Trump to attack Iran was seen by some neocons as further evidence the president was a non-interventionist at heart, some even suggesting, when it comes to using military force, he’s more like Obama than George W. Bush. “There is fear in him (Trump),” scolded New York Times columnist Bret Stephens.

It was bad enough neocons had to bite their collective tongues every time Trump mentioned the need for a U.S. military withdrawal from their pet projects in Syria and Afghanistan. Along with refusing to attack the Iranians over a drone, Trump soon followed up that decision with the suggestion that he was open to new negotiations with the Iranians over their nuclear program. A backbreaking-no-no in neocon world.

If neocons are consistent on anything, it is their religious-like devotion to the belief that diplomacy doesn’t work with America’s foes.

On that point, September 2019 saw the last straw for Trump’s national security advisor John Bolton, who was often more of an advocate for his own policy ideas than a steward for Trump’s. The breaking point for Bolton? A planned (though eventually cancelled) meeting with the Taliban at Camp David. Not only would such talks be “doomed to fail,” according to Bolton, they would be disrespectful to the families of 9/11 victims.

Trump would fire Bolton that same September (or Bolton resigned, depending on who you ask), and barely a week after his exit, Bolton was launching sharp, thinly-veiled attacks on his former boss at a private luncheon at the Gatestone Institute in New York City. The think tank, created in 2008 by Sears Roebuck heiress Nina Rosenwald, focuses on rolling back political Islam and the “Islamization” of non-Muslim societies, and provided the perfect platform for Bolton (who is now on Gatestone’s payroll) to signal to his neocon kinsfolk this one important message: Trump is not one of us and cannot be trusted.

Reinforcing that critique, Trump himself responded to Bolton’s criticisms by reminding everyone that he was not, in fact, a neocon interventionist:

“I was critical of John Bolton for getting us involved with a lot of other people in the Middle East. We’ve spent $7.5 trillion in the Middle East and you ought to ask a lot of people about that. John was not able to work with anybody, and a lot of people disagreed with his ideas. A lot of people were very critical that I brought him on in the first place because of the fact that he was so in favor of going into the Middle East, and he got stuck in quicksand and we became policemen for the Middle East. It’s ridiculous.”

Trump would nonetheless make significant attempts after the Bolton firing to regain support among his neocon constituents.

However, even the impulsive (and arguably counterproductive) assassination of Iran’s top general, Qasem Soleimani, on January 3, 2020, was not enough to allay concern among neocons about Trump’s trustworthiness to stand by his previous neocon policies (i.e., an attempted coup in Venezuela, ongoing support for a Saudi-UAE regime change war in Yemen, the marginalization of Palestinians interests in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the ratcheting up of Cold War-like rhetoric against China, etc.).

Where the Bolton Revolt offered evidence that neocon intellectuals were bailing on Trump, perhaps more distressing to the Trump re-election effort were early signals from the GOP’s billionaire donor class that their financial support for Trump 2020 was not to be taken for granted — a group that included Rebekah Mercer, a billionaire heiress who has a history of supporting neocon organizations including Gatestone.

Whether he knew it or not, Trump may have sealed his electoral fate when he cancelled the Iran airstrikes on June 20, 2019.

What is a neoconservative, really?

As with so many of the terms and labels commonly thrown around in the political news media, the term neocon (short for neoconservative) is not as well-defined as one might think.

Political historians generally trace the term back to the 1960s and a group of prominent Democrats — such as Washington Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson — who were alarmed by their party’s growing pacifism during the Vietnam War. In that period, neocons were politically liberal (i.e., generally support civil liberties and social justice) but much more interventionist and open to the use of military force when it comes to foreign policy.

In the 1970s, however, the term neocon came to represent post-Vietnam Republicans who wanted to move past the debacle of the Nixon presidency (particularly the culture war issues) and return the party’s focus towards promoting a robust U.S. military and muscular foreign policy.

Over time the neocon label has been increasingly applied to politicians from either party (i.e., Hillary Clinton, Dick Cheney) and is generally attached to politicians and foreign policy leaders who believe military force is often a viable option when dealing with our country’s adversaries; and, in some cases, may be the only constructive option.

Neocons are commonly distinguished from foreign policy realists in that the latter typically advocate for the use of military force only when U.S. interests are directly attacked or an important strategic interest is at stake (i.e., fascist control of Europe, threats to world oil supplies); whereas, neocons are more comfortable with the U.S. military being the ‘free world’s police force’ and do not necessarily require a direct threat to U.S. strategic interests (i.e., Syria, Yemen, 2003 Iraq War). Indeed, neocons often justify the use of military force simply to promote regime change within authoritarian nations we don’t like.

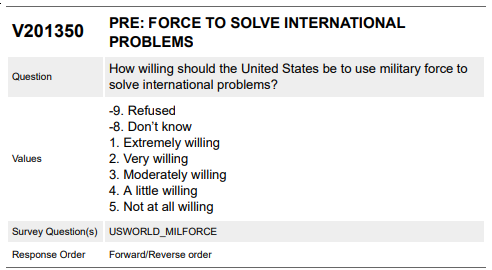

These are broad definitions and, as such, can lose their empirical value when they are distilled down to one or two attitudes and encompass a large swath of the American public. Nonetheless, how Americans answered this simple question heading into the 2020 presidential election — How willing should the U.S be to use military force to solve international problems? — may have had a significant relationship to the election outcome.

Are there enough neocon-aligned Americans to change a presidential election outcome?

How many eligible voters in the U.S. are potentially attracted to neocon policy preferences? Are there enough to sway a presidential election? The short answer is: YES.

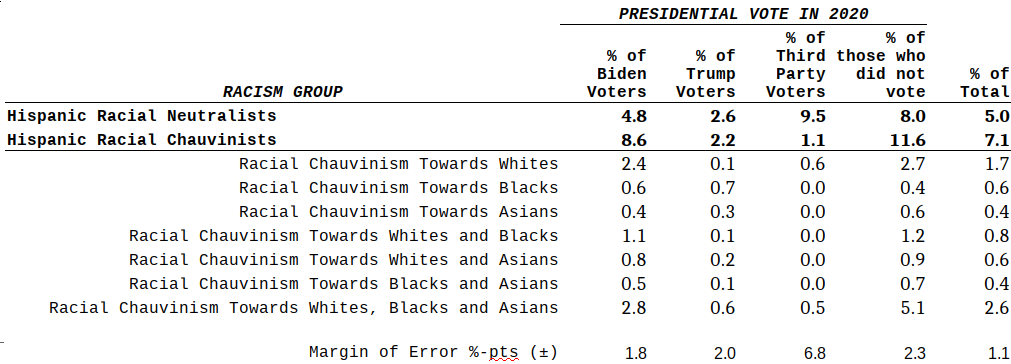

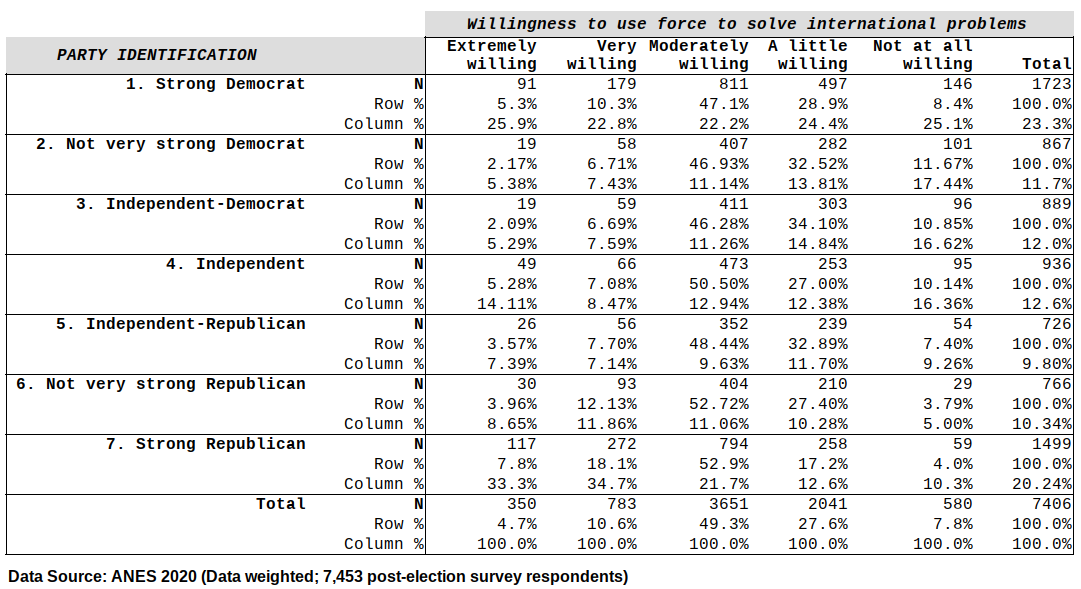

The 2020 American National Election Study (ANES) conducted by The University of Michigan and Stanford University before and after the 2020 election offers some insight on this question (see Appendix A for a description of this study and Appendix B for a list of key questions from the 2020 ANES). Figure 1 breaks out the number of ANES 2020 respondents according to their “willingness to use force to solve international problems” and the strength of their party identification.

Figure 1: Willingness to Use Force by Party Identification (ANES 2020)

About 15 percent of U.S. eligible voters are “extremely” or “very” willing to use military force to solve international problems (4.7% + 10.6%). That is 36.6 million eligible voters — who I presume are the Americans most open to neocon policy ideas.

Among those 15 percent, 58 percent are strong partisans — which translates to almost 9 percent of the 239 million Americans eligible to vote in 2020 (or about 21.2 million people).

Of those 21.2 million people, 8.7 million are “strong” Democrats and 12.5 million are “strong” Republicans, according to the 2020 ANES.

[Note: 81.3 million people voted for Biden and 74.2 million people voted for Trump in 2020 — a difference of 7.1 million votes.]

Since strong partisans are far more likely to vote than weak partisans, getting these potential voters to the polls is a high priority for any presidential campaign.

But was Trump able to keep the vast majority of strong, neocon-aligned Republicans in 2020?

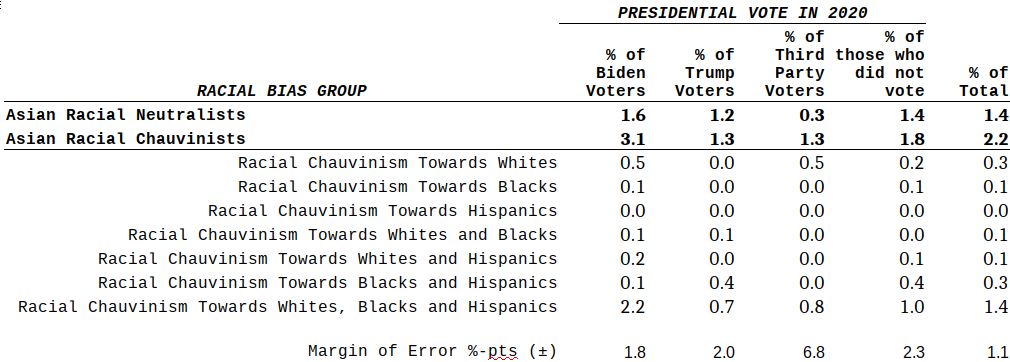

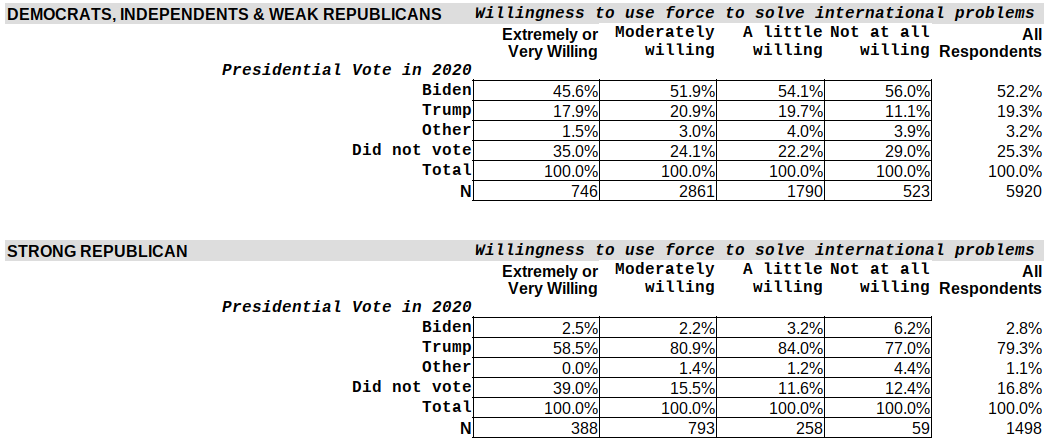

The start of that answer is in Figure 2 which shows a strong relationship between strength of party identification (in this case, ‘Strong’ Republicans versus ‘Weak’ Republicans, Democrats and Independents), attitudes regarding ‘use of force to solve international problems,’ and 2020 presidential vote choice.

Figure 2: Presidential Vote Choice in 2020 by ‘Willingness to Use Force’ and Strength of Party ID

Seventy-nine percent of ‘strong’ Republicans voted for Trump, while only 3 percent of those voters defected to Democratic candidate Joe Biden. Another 17 percent did not vote and one percent voted for a third party candidate. Conversely, 79 percent of ‘strong’ Democrats voted for Biden, while a mere 2 percent voted for Trump (data not shown in Figure 2). Nineteen percent of ‘strong’ Democrats did not vote and one percent voted for a third party candidate.

The striking finding in Figure 2, however, is the drop off in Trump’s support among ‘strong’ Republicans who are ‘extremely’ or ‘very’ willing to use force to solve international problems (henceforth, referred to as Republican neocons). Only 59 percent of Republican neocons voted for Trump, compared to 81 percent of other ‘strong’ Republicans.

This is an astonishing decline in support among what should be loyal Republican partisans. In numbers, this means 883,000 Republican neocons abandoned their party’s incumbent president in the 2020 general election.

Is that enough to change the outcome an election in which Biden beat Trump by 7.1 million votes and 74 electoral votes?

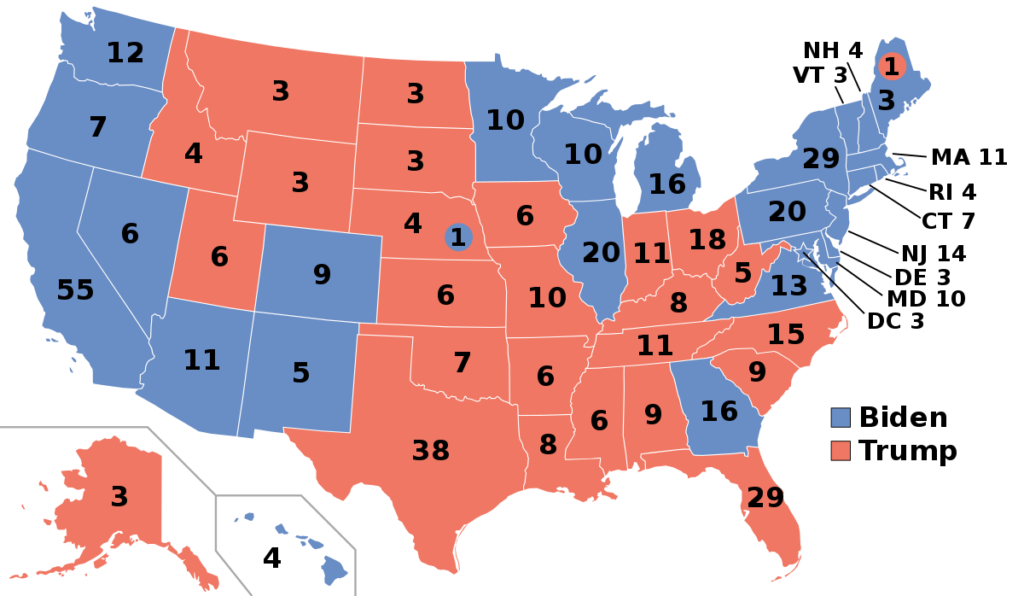

If we add those 883,000 “lost” Trump votes across the states (plus D.C.) in proportion to each state’s vote eligible population (and assume all of them were originally non-voters and, therefore, we do not subtract them from Biden’s state vote totals), Trump would win two states he had originally lost: Arizona and Georgia — which, together, are worth 27 electoral votes.

[The spreadsheet where I conducted this analysis is available on GitHub.]

Trump would have still lost the election by 20 electoral votes had the Republican neocons voted as loyally for Trump as other “strong” Republicans.

For Trump to win, he would still need to close a 45,000 vote gap in Pennsylvania and a 4,600 vote gap in Wisconsin.

But what if there are there other Republican neocon voters we did not consider in the previous analysis? What if someone is ‘moderately’ willing to use force to solve international problems? Could they not also be considered a neocon-aligned voter?

The following statistical analysis attempts to answer that question…

A Vote Model of the 2020 Presidential Election

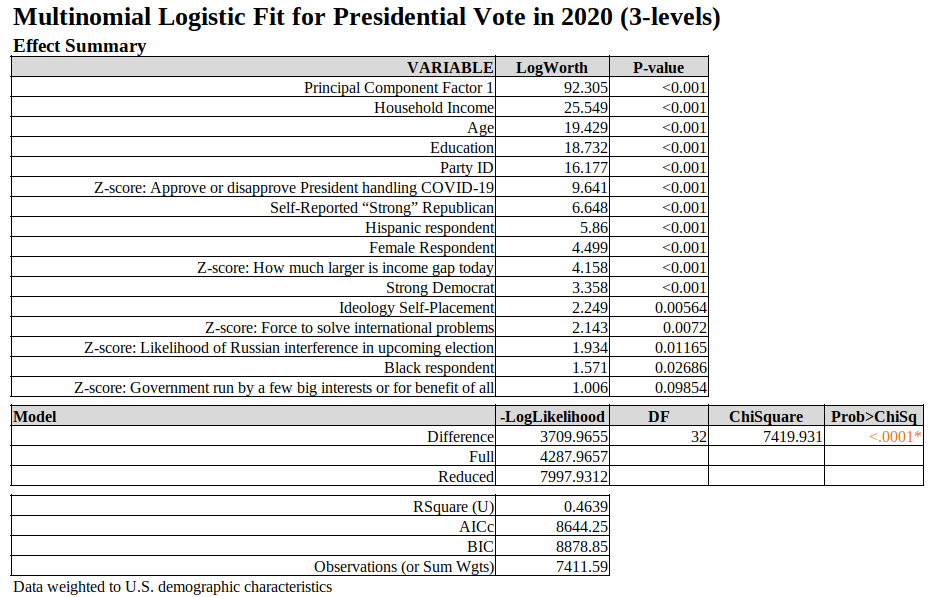

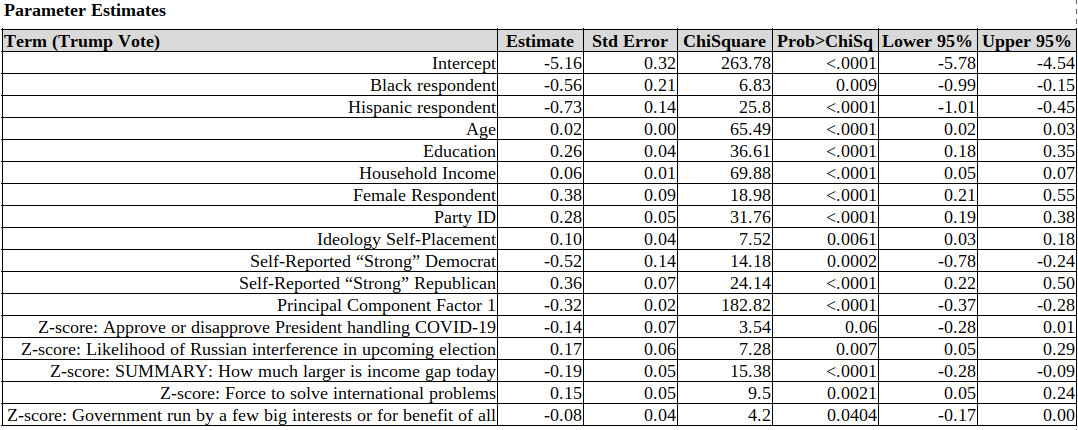

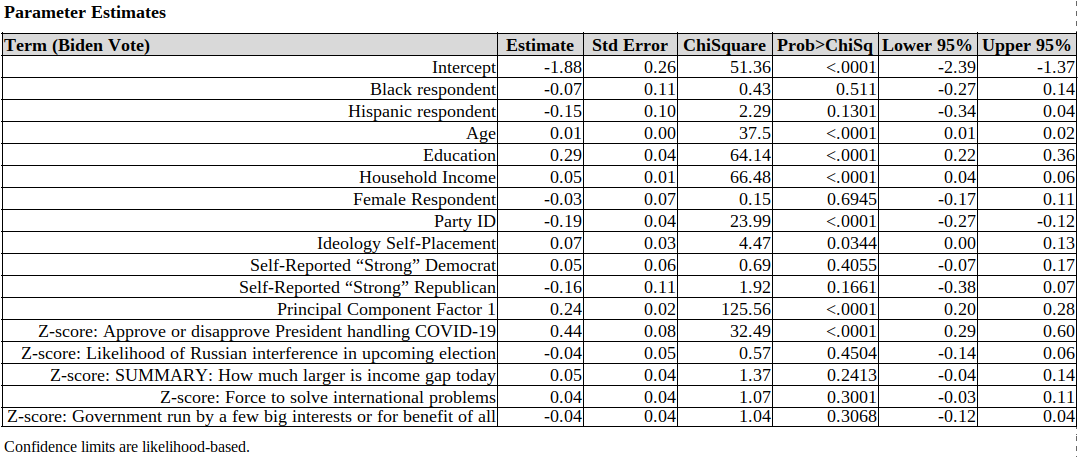

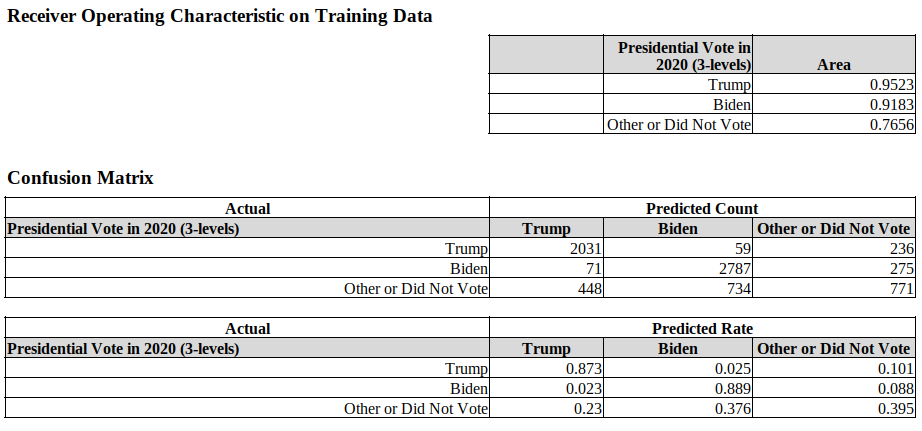

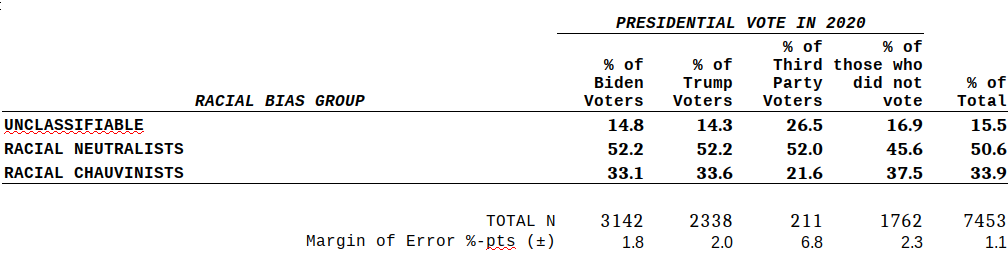

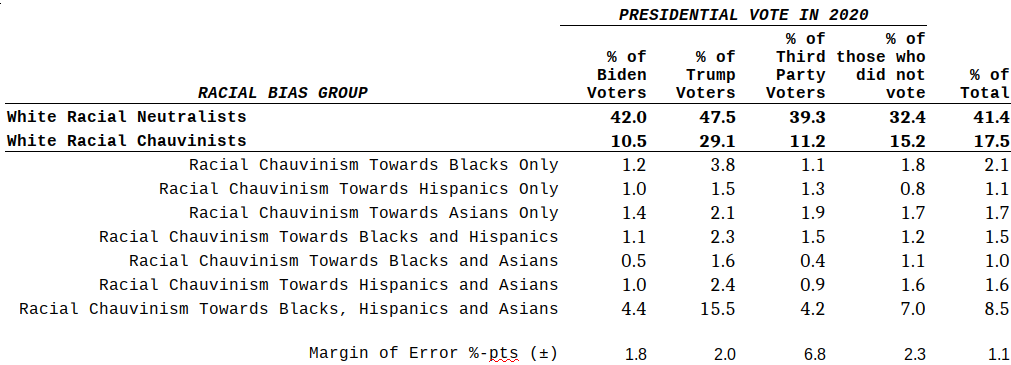

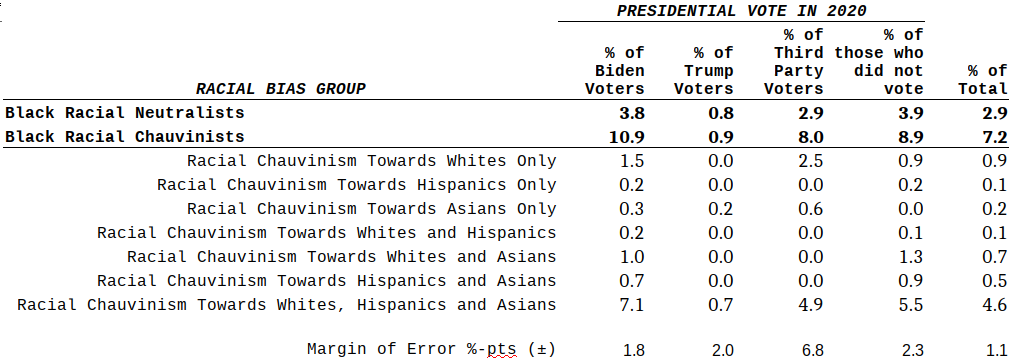

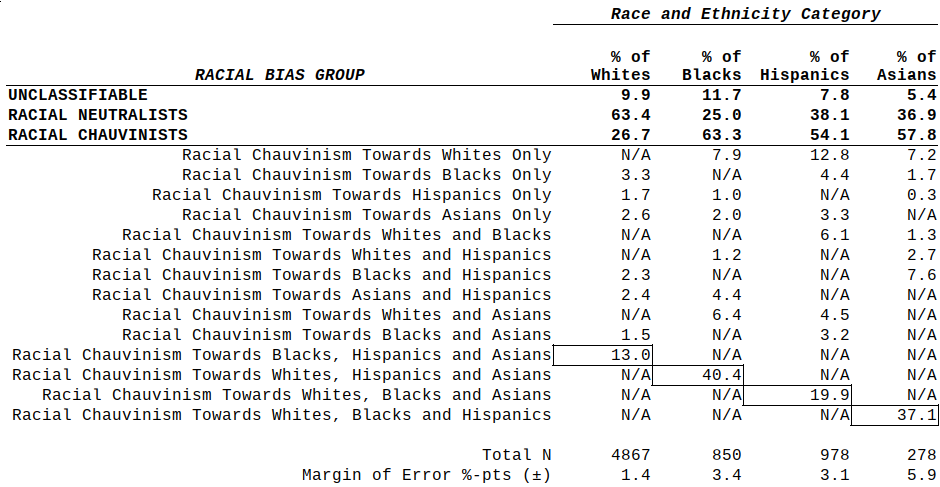

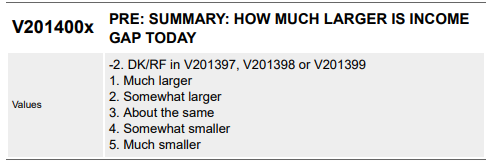

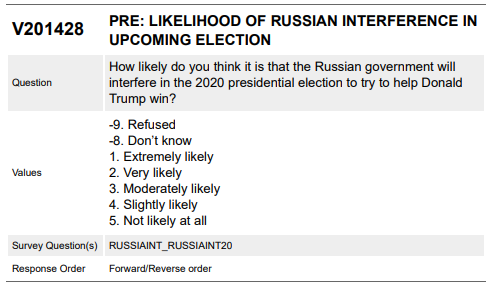

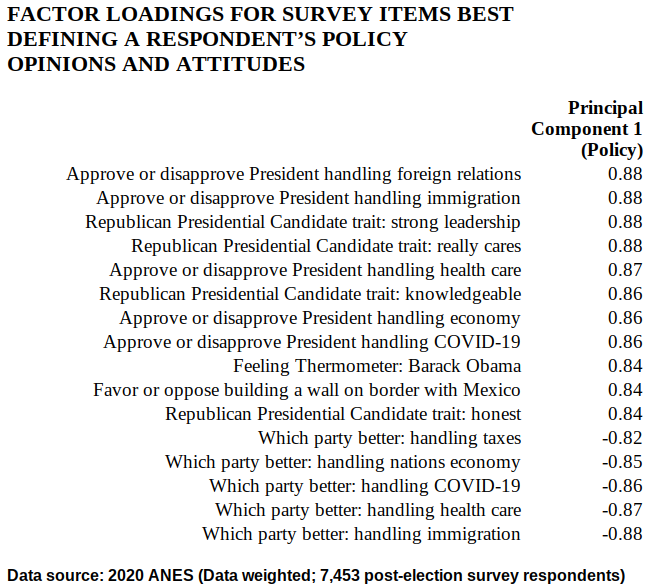

Using the post-election respondents from the ANES 2020 (a weighted total of 7,453 eligible voters), I estimated a multinomial logistic model for the 2020 presidential vote using a 3-level vote indicator (Trump, Biden, Non-voter/Third party voter) as the dependent variable.

The statistically significant independent variables in the model included:

- Index of Partisan Policy Preferences (see Appendix C for a list of standardized survey items used to construct the index)

- Demographics: Household Income, Age, Sex, Education, Race/Ethnicity

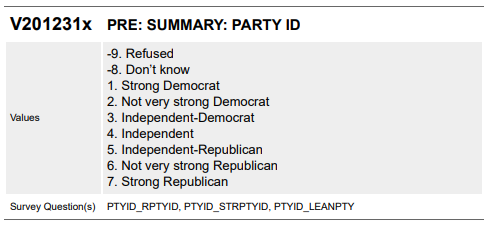

- Party Identification and Strength of Party Identification

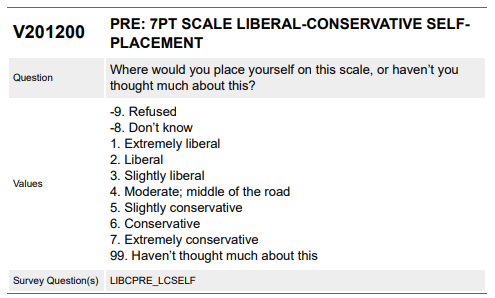

- Ideological Self-Placement (Liberal — Moderate — Conservative)

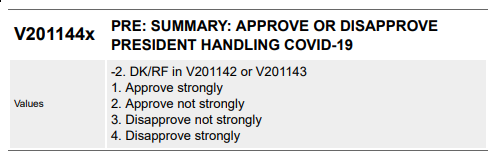

- Approval/Disapproval of President Trump’s Handling of COVID-19

- Perception of Changes in Income Gap

- Perceived Likelihood of Russian Interference in 2020 Election

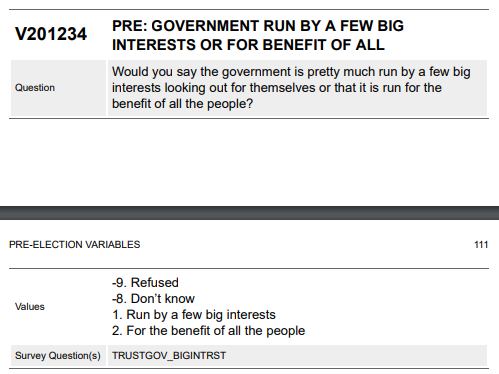

- Perception that Government is Run by a Few Big Interests

- Willingness to Use Force to Solve International Problems

For the purposes of this essay, I will concentrate on the findings related to a respondent’s willingness to use force to solve international problems — which I consider an indicator of a respondent’s openness to neocon policy ideas.

[The full model estimates and diagnostics are in Appendix D and the dataset used to generate these results are available on GitHub.]

Results

Overall, a respondent’s willingness to use force was a significant predictor of a Trump vote in 2020 (Chi-square = 9.5, p < .002). More specifically, the more willing a respondent said they were to use force to solve international problems, the less likely they were to vote for Trump (see Appendix B for the variable’s coding scheme).

After controlling for a number of important factors commonly associated with a person’s vote choice (e.g., age, education, income, party ID, policy preferences), attitudes on Use of Force was still significant in the margins. But enough to alter the 2020 election outcome?

To estimate the electoral impact of attitudes on Use of Force, I first identified those respondents where the model predicted a Trump voter when, in fact, the respondent voted for Biden. Next, I further filtered down to those respondents who answered “extremely,” “very,” or “moderately” willing to use force to solve international problems — in other words, neocons who we would have expected to vote for Trump, but voted for Biden instead.

In the ANES 2020, they are represented by a scant 45 respondents (or 0.6 percent of the total sample). But that translates to 1.43 million voters in the 2020 election.

Similar to the first analysis, I added those 1.43 million “lost” Trump votes across the states (plus D.C.) in proportion to each state’s vote eligible population (but this time also subtracting them from Biden’s state vote totals). After doing this, the adjusted state-level vote totals end up flipping not just Arizona and Georgia (as in the first analysis), but also Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. Those 57 electoral votes would have given Trump 289 electoral votes to Biden’s 249.

If Trump had kept the Republican neocons in his camp, he would have won the 2020 election.

[The details behind this second analysis can also be found on GitHub.]

Final Thoughts

Obviously, this is all very speculative. For example, there are other attitudinal variables (expectations of Russian interference, perceived changes in income inequality, Trump’s handling of COVID-19) that were significant predictors of the 2020 vote choice and could have impacted the election outcome.

I just as easily could have shown evidence that disapproval of Trump’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic impacted enough votes to give Biden the victory.

Or expectations of Russian election interference. Or the growing income gap. Or the belief that Washington, D.C. is controlled by a few big money interests.

All were significant factors in the 2020 presidential election, in isolation or considered together.

If anything, this analysis reminds us that the 2020 election was closer than we may remember. Four states. That was the difference.

Trump still could have won, even with an unprecedented level of media hostility and a worldwide pandemic erupting on his watch.

And, so, it does not seem laughable or implausible that the 2020 outcome was changed by a relatively large, motivated group of neocon Republicans — an identifiable faction openly upset about a number of Trump foreign policy decisions (or threatened decisions).

I believe they did.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: nuqum@protonmail.com

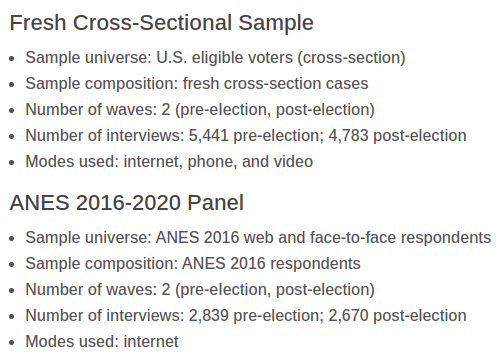

APPENDIX A: The American National Election Study (2020)

The American National Election Study 2020

Data collection for the ANES 2020 Time Series Study pre-election interviews began in August 2020 and continued until Election Day, Tuesday (November 3). Post-election interviews began soon after the election and continued through the end of December. This field period began earlier than the traditional ANES field period, which typically starts the day after Labor Day and concludes the day before Election Day.

The ANES 2020 Time Series Study features a fresh cross-sectional sample, with respondents randomly assigned to one of three sequential mode groups: web only, mixed web (i.e., web and phone), and mixed video (i.e., video, web, and phone). The study also features re-interviews with 2016 ANES respondents (conducted by web), and post-election surveys with respondents from the General Social Survey (GSS).

Figure A.1: Summary of ANES 2020 Survey Methodology

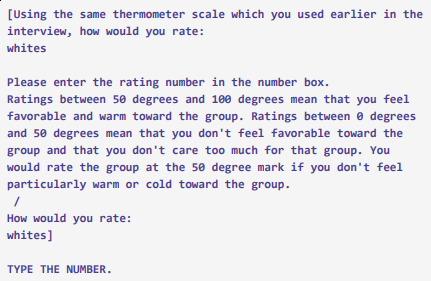

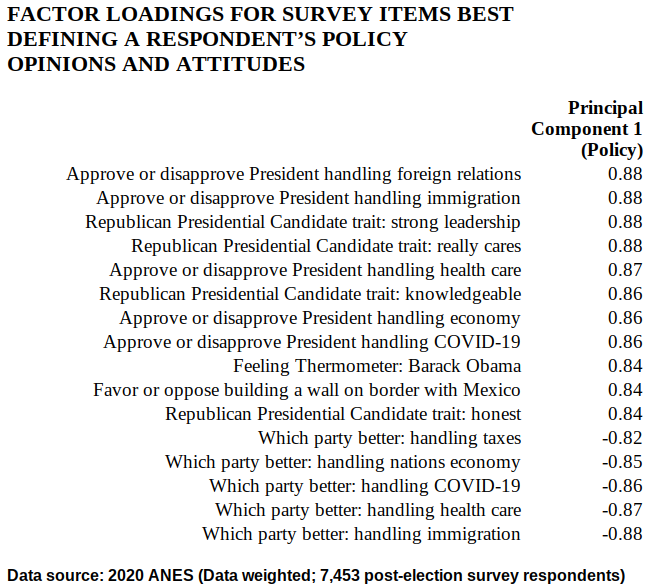

APPENDIX B: Survey Items Best for Defining Respondent Policy Preferences (Principal Component Analysis)

APPENDIX B: Coding of Key Questions from 2020 ANES

APPENDIX C: Survey Items Best for Defining Respondent Policy Preferences (Principal Component Analysis)

APPENDIX D: Detailed Output for Multinomial Logistic Model for the Presidential Vote in 2020