By Kent R. Kroeger (April 20, 2023)

Category Archives: Science

Simple liars, damned liars, and experts.

By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, September 11, 2022)

I’ve written elsewhere about lying. And readers have openly disputed my view on the issue. “Speaking ignorance is a type of lying,” wrote one reader.

No, it is not. Spreading ignorance is what communications researchers call misinformation, which is distinguishable from disinformation, which is the deliberate promulgation of false information (i.e., lying).

Ignorance is not a form of lying. To suggest otherwise is to indict everyone as serial liars.

If your education and experience leads to believing things that are not true, that is not necessarily on you, it can also be the result of the institutions, environment, and peer groups within which you were informed.

Subsequently, when you utter nonsense, you are not a liar — your are just ill-informed. We are all subject to that harsh critique. I utter nonsense on a daily basis. [I believe Aaron Rodgers is the greatest quarterback in NFL history — no joke, I really do.]

I may be wrong on this topic, but I am not a liar. I simply have failed to accept the evidence that contradicts my deeply-ingrained beliefs and impenetrable Packer fandom.

We are all guilty of this type of intellectual failure. Practically speaking, independent of our IQs, experience and education, we can be seduced into wrong, even if well-intentioned, thinking.

Opinions are everywhere.

Men can become women? And vice versa? The U.S. can’t afford a national health care system? The U.S. can afford to pay off student debt for financially insecure students? Nuclear power is safe? The Yemeni Houthis are an existential threat to Saudi Arabia? The 2022 presidential election was stolen? The 2016 presidential election was stolen? Nicolas Cage is one of Hollywood’s greatest actors? These are not necessarily empirical hills on which I would want to die, though I do have opinions on each. But they are just that — opinions, not indisputable facts.

And, and in most cases, a wrong opinion on any issue is not due to getting our information from liars (though they do exist), but more likely the result of the experts we rely who are misinformed and/or biased which subsequently clouds their judgment and, by extension, ours.

It is not a bad habit to question everything you read, hear or see. That doesn’t mean you need to avoid strong beliefs or opinions — but it would be wise to prepare to be wrong.

I always am.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: kroeger98@yahoo.com

The news media deserves some of the blame for vaccine hesitancy

By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, January 3, 2022)

[Author’s Note: The opinions and errors found in this essay are mine alone. And do not make personal health or financial decisions based on this essay.]

“If you don’t read the newspaper, you are uniformed. If you do, you’re misinformed.”

— Mark Twain

Back in September, wearied by five plus years of analyzing the destructive synergisms that define American politics and the national news media, I decided to take a few months off from following our nation’s dysfunction.

I needed a break. (We all do.)

So, I stopped watching cable TV news, avoided social media, limited my news consumption to the online versions of the New York Times and Wall Street Journal, and, for entertainment purposes, occasionally indulged in my favorite political podcasters like Krystal Ball and Saagar Enjeti (Breaking Points), Kyle Kulinski, Ben Shapiro and Jimmy Dore.

Though unverified through medical professionals, I believe my systolic blood pressure has gone down ten points over this period. And this is despite the real pressures of inflation, raising a teenage son, keeping a marriage intact, and limiting job stress, all while navigating the pandemic.

As to why one might benefit from avoiding the mainstream news media, my hunch is that its daily offering of divisive, anxiety-inducing content is a public health hazard. That is how they attract audiences and make money: Keep everyone uncertain and agitated. And this is the goal whether the media outlet leans left, right or towards the middle on the political spectrum.

In the end, this business model is destructive to the physical and mental health of our nation, and there is evidence to support such a contention.

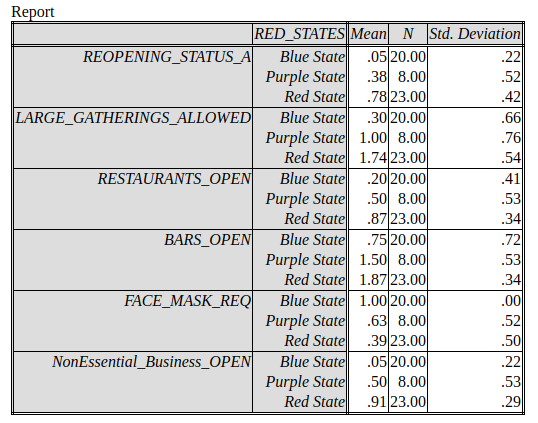

Vaccine hesitancy among Republicans and conservatives

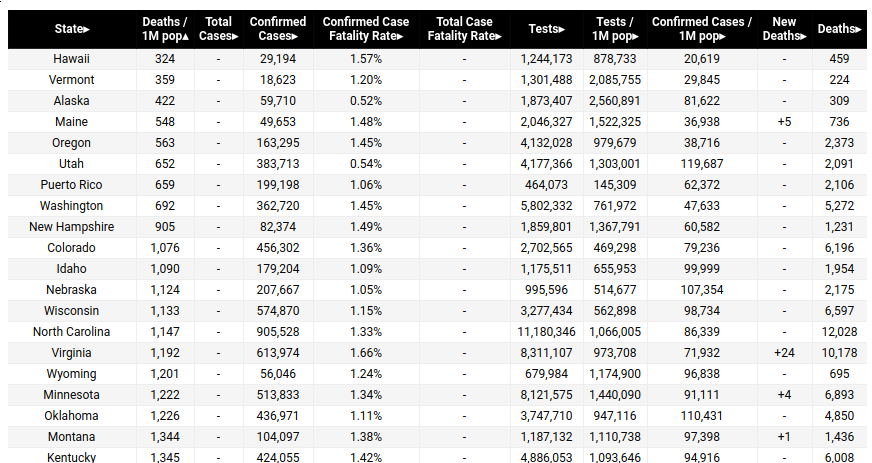

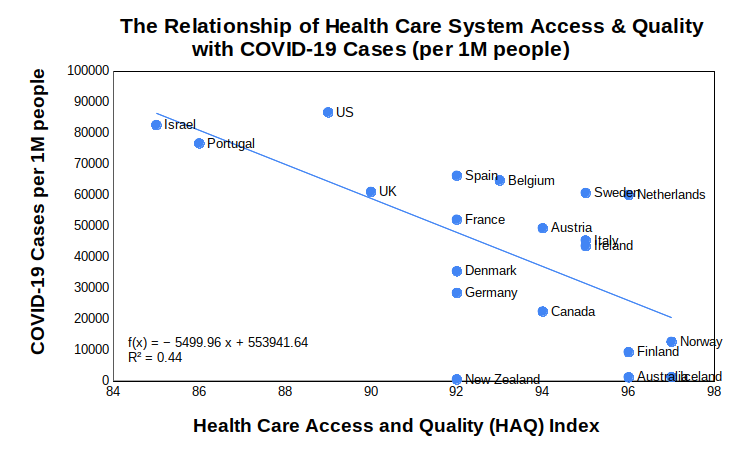

Nowhere is the deadliness of misinformation more apparent than the stubbornly large percentage of American adults who continue to resist getting vaccinated against COVID-19.

According to the New York Times COVID-19 vaccination tracker, 27 percent are not fully vaccinated, and 14 percent of American adults have not received even one jab. While it is true that relatively low vaccinations rates exist among Black (67%), less-educated (68%) and younger adults (67%), the lowest vaccination rate is among Republicans (59%), according to the Kaiser Foundation.

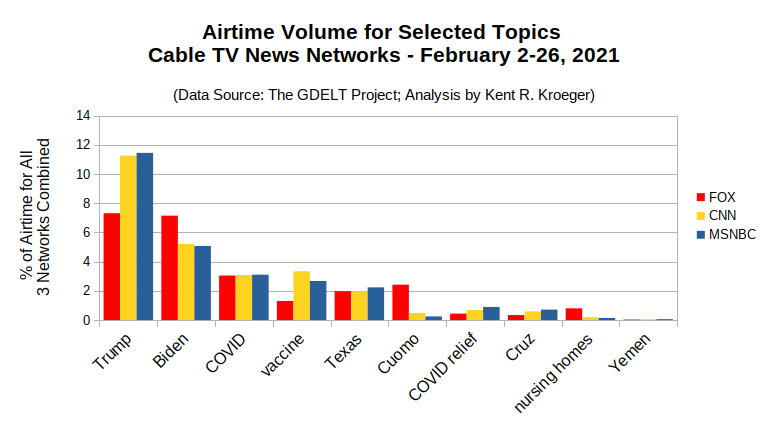

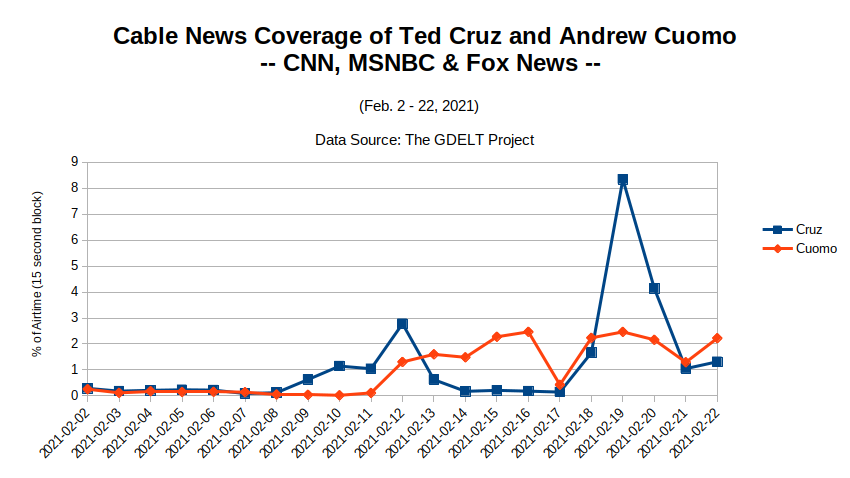

But the popular myth about vaccine hesitancy is that it is mainly the product of misinformation about the safety of the COVID-19 vaccines being propagated by conservative media outlets such as the Fox News Channel. To be fair, the Fox News has provided a large, influential platform for vaccine skeptics to plant seeds doubt about vaccine safety and effectiveness. But even The Washington Post acknowledged last summer that Facebook is a more powerful source for vaccine misinformation than Fox News.

However, I offer a more essential cause of the disproportionate level of vaccine hesitancy among Republican and conservative Americans: a deep and understandable distrust of the mainstream media that has repeatedly omitted, exaggerated, and misrepresented key facts to the detriment of conservatives and their values.

Do you need examples? Here is just a small sampling from over the past six years (in no particular order):

- The January 6th Capitol protests and misrepresentation of Capitol Officer Brian Sicknick’s death (which would lead the New York Times to walk back their original narrative about his death being the direct result of a physical assault by pro-Trump protestors),

- Cable TV news networks declared the May 2020 George Floyd protests as ‘mostly peaceful’ as businesses and cars burned in the background,

- Misreporting key facts on the Trump January 2021 phone call to Georgia Vote Fraud Investigator prior to the state’s special Senate election,

- Failure to acknowledge the active debate in the scientific community over the SARS-CoV-2 lab leak versus natural origin hypotheses,

- Russiagate (the specific media inaccuracies over which are too many to list here, but journalist Glenn Greenwald made an early attempt),

- Douma chemical attack in Syria, where reporting by award-winning journalist Aaron Mate (The Grayzone) significantly called into question mainstream reporting on the attack,

- Failure to report the policy origins and undercount of the disproportionately larger number of nursing home deaths in New York during the early months of the COVID-19,

- Failure to cover the Hunter Biden laptop story during the 2020 election campaign, which would lead some news outlets (notably NPR) in late September 2021 (!) to correct their original assertion that the story had no merit,

- Media reports of Trump ordering tear gas to clear a protest crowd that were subsequentlycontradicted by an Inspector General report on the event,

- Months before the 2020 election, news outlets claimed Russians were paying a bounty to the Taliban to kill US soldiers (and Trump did nothing about it, they also reported); in truth, the bounty story came from a highly unreliable intelligence source that even U.S. intelligence has since disavowed; media retractions of this story would only come after the 2020 election.

- Rolling Stone’s story on Ivermectin overdoses overwhelming the emergency rooms of an Oklahoma hospital at the expense of gunshot victims was utterly false and would need to be retracted days after its initial publication,

- New York Times grossly overstated the number of child fatalities for COVID-19,

- CNN and other news/entertainment outlets reported that podcaster Joe Rogan took horse de-wormer for COVID-19;when, in fact, he took a doctor-prescribed, human-safe amount of the drug Ivermectin,

- The Washington Post revised an article and deleted the Twitter post promoting it after saying the November 2021 Christmas parade massacre in Waukesha, Wisconsin was “caused by an SUV.”

- Coverage of the Kyle Rittenhouse trial included numerous mistakes, critical omissions (e.g., rarely mentioning that all parties involved were white) and smears (e.g., Rittenhouse referred to as a ‘white supremacist’ without supporting evidence).

Occasionally inaccurate reporting is an unavoidable part of aggressive journalism. It happens. And, God knows, Fox News and other conservative news outlets have misrepresented facts due to their own partisan biases and sometimes careless inattention to detail and complexity.

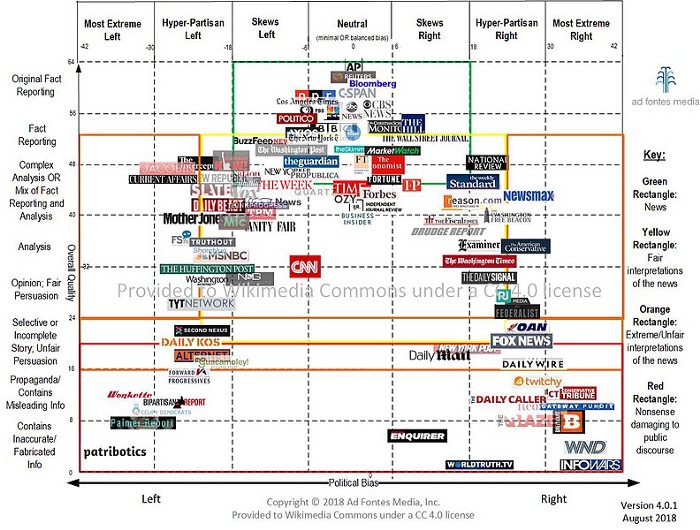

However, there is something telling and deeply ominous when “trusted” news outlets like the New York Times and The Washington Post so consistently err in one ideological direction when they do make errors. I don’t believe this is random chance. It is the result of a long-developing, pervasive news media bias in favor of establishment-friendly opinions and narratives at the expense of critics to that establishment. (If you want evidence of this growing media bias, here are some good places to start: Here, here and here.)

Distrust of elites drives vaccine hesitancy

Over the past months I talked directly to unvaccinated people I met at my favorite local watering hole (and whose customers are largely working class people from western New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania). It was not a scientific probability sample, but it served the purpose of collecting examples of how people articulate their hesitancy to get one of the COVID-19 vaccines.

My first observation was that most people at this small pub were vaccinated. Still, over the course of a few weeks, I talked to no less than a dozen unvaccinated people and queried them on their reasons for staying unvaccinated. Their responses almost universally included these two themes:

(1) Lack of trust in what they hear in the news media from media, political and science elites,

(2) A belief that they are healthy and would prefer the risks of COVID-19 than the unknown risks of the vaccines.

Young males, who were roughly half of my convenience sample, were particularly likely to cite their good health as a reason not to be vaccinated, and also would frequently express concern that the vaccines could harm their fertility. In fact, Green Bay Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers recently offered this fertility argument as one of the reasons he didn’t get vaccinated.

[The peer-reviewed research I have found on the subject of COVID-19 vaccines and male fertility has found no evidence of increases in male infertility as the result of getting a COVID-19 vaccine.]

But it is the first reason (‘lack of trust’) that I suspect drives most vaccine hesitancy in the U.S., particularly the interrelationship between someone’s trust in the news media, politicians, and science.

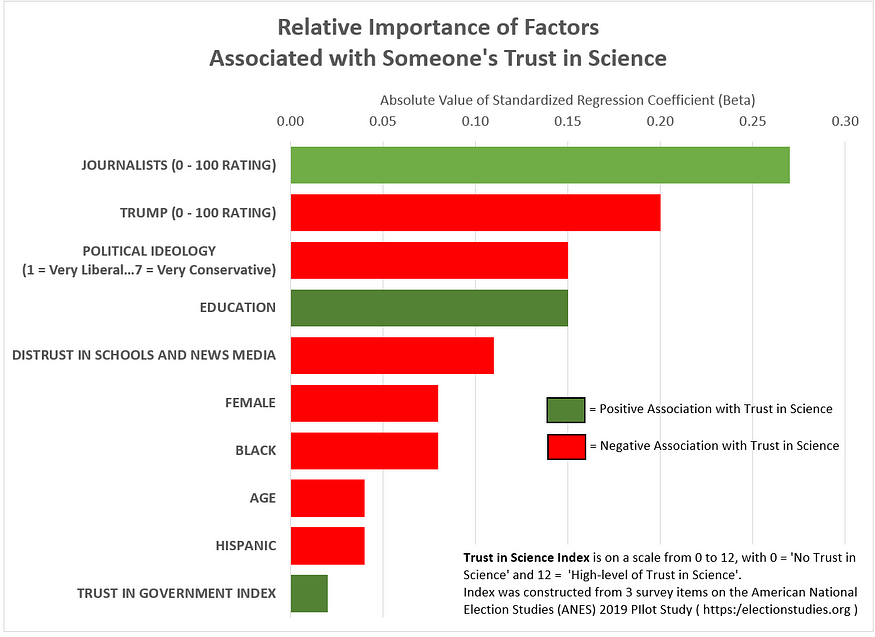

The 2019 American National Elections Pilot Study, administered by researchers from the University of Michigan and Stanford University, offers evidence that people’s level of trust in science is primarily founded on their level of trust in journalists and the news media.

When someone’s trust in the news media is undermined — such as, when they believe the news media is continually deceiving them for partisan and social class reasons — trust in science suffers.

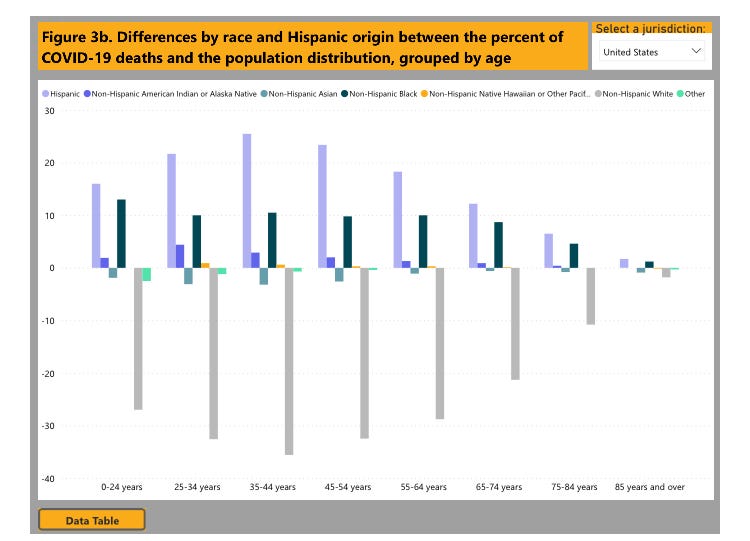

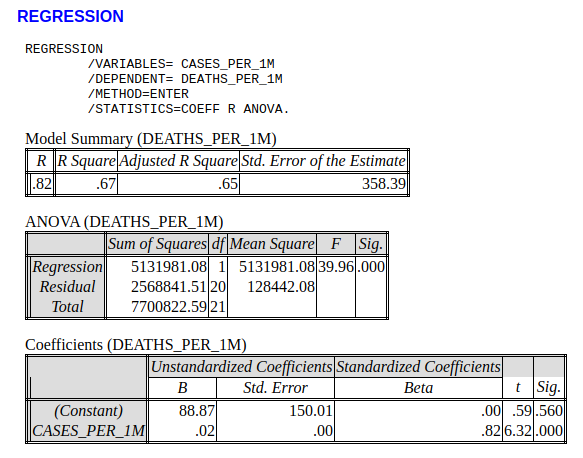

In Figure 1 (below), the standardized regression coefficients from a linear regression model using the 2019 ANES data are reported. The dependent variable is a 12-point scale indicating a person’s level of trust in science. Among the significant independent variables in the model, the most significant factor associated with a person’s trust in science is a person’s favorability towards journalists. Also interesting is that being Black or Hispanic— independent of political ideology or attitudes towards the news media or — is significantly associated with distrust in science.

Figure 1: What factors are associated with a person’s trust in science?

Similarly, before the lack of trust in science among some Americans is blamed on Fox News and Republicans, it must be explained why favorability towards journalists is highly related to trust in science, regardless of someone’s political ideology, support for Donald Trump, level of education, sex, or race/ethnicity.

My hypothesis is that, given the mainstream news media (including Fox News) serves such a narrow spectrum of Americans, drops in trust in journalists and, by extension, science were inevitable.

Our national news outlets represent the priorities, opinions and biases of rich, white liberals. These news sources are not objective. Worse yet, they systematically misinform anyone who digests their daily product.

And this central bias in the mainstream news media has not gone unnoticed by conservatives, particularly among the working-class who are so often a punching bag for news media elites.

One of the ugliest (and most socially destructive) arguments finding popularity in the national news media’s coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic is the suggestion that people who aren’t vaccinated should not be given the same priority for medical care as those who have vaccinated.

The once-funny, now drearily partisan Jimmy Kimmel (host of ABC’s Jimmy Kimmel Live!) exemplified this toxic kind of thinking in a recent monologue:

Kimmel opined on his show:

“The number of new cases is up more than 300 percent from a year ago. Doctor Fauci said that if hospitals get any more overcrowded they’re going to have to make some very tough choices about who gets an ICU bed. That choice doesn’t seem so tough to me — vaccinated person having a heart attack, yes, come right on in. We’ll take care of you. Unvaccinated guy who gobbled horse goo, rest in peace wheezy.”

Stories of families unable to get their sick parent or child admitted to a hospital ICU ward because those beds are filled with unvaccinated COVID-19 patients permeated the news media last fall.

Those stories are real and tragic…and, yes, I believe the unvaccinated need to understand how their health care decisions are, writ large, impacting their communities.

Yet, there is something seriously wrong if a consensus of Americans think the vaccine hesitant deserve the death penalty for their personal decision regarding vaccines. People accepting the COVID-19 deaths of thousands of Americans in “Trump” country as their ‘just desserts’ need to rethink their values.

More compassionate Americans understand that health care should never be rationed based on background or past behavior. President Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act (ACA) is predicated on that premise.

John Barro, senior editor and columnist at Business Insider, spelled out this ACA feature on the Rising podcast last year:

“One of the key ideas behind the Affordable Care Act (ACA) — and by certain laws that led up to the Affordable Care Act, like the HIPA law — was about making sure that people with pre-existing conditions could get health insurance at the same price as people who don’t have those conditions. And the reason that we focus on having on having those rules is otherwise it can become very unaffordable for people to get health insurance if they have previously had cancer or if they have diabetes or they have other pre-existing conditions.

Our view is that health insurance is not like other insurance products. It is not like auto insurance or homeowners insurance, where, if you live on the ocean you’re going to pay more for hurricane coverage. If you have a swimming pool you’re going to pay more for liability. If you’ve got speeding tickets you pay more for auto insurance.

Health insurance laws are structured to ensure availability to as many people as possible. We have fought to de-link pricing from health risk.”

Today, too many Democrats and liberals are happy to discard the ACA’s central pricing rationale so that they can punish people they consider ‘ignorant’ and ‘deplorable.’ “Rest in peace wheezy,” sneers Kimmel.

Ironically, working-class conservatives aren’t the only ones burying themselves in ignorance regarding COVID-19. Democrats and liberals have their own intellectual blind spots on the subject matter.

The poor understanding of COVID-19’s hospitalization risk among liberals and Democrats

Coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic by the left- and center-leaning news and entertainment outlets has led to large reservoirs of misinformation residing among liberals and Democrats.

A few months ago on Jimmy Kimmel Live!, Bill Maher, host of HBO’s Real Time with Bill Maher, made a surprisingly sharp observation about the national media’s unmistakable penchant for fostering undue fear about the COVID-19 pandemic:

“I have to cite a survey that was in the New York Times, which is a liberal paper, so they weren’t looking for this answer. The question was: “What do you think the chances are that you would have to go to the hospital if you got COVID?”

The Democrats thought that (probability) was way higher than did Republicans. The answer is between one and five percent. Yet, 41 percent of Democrats thought it was over a 50 percent chance and another 28 percent thought it was between 20 and 49 percent — so 70 percent of Democrats thought it was way higher than it really was.

Liberal media has to take a little responsibility for scaring the (bleep) out of people.”

This overestimate of COVID-19’s hospitalization risk most likely keeps a large percentage of Americans submissive to a variety of ineffective policy measures meant to contain SARS-CoV-2, but which have little scientific evidence to support their implementation (e.g., broad outdoor mask mandates, closing public parks, testing vaccinated people who lack symptoms, prohibiting out-of-home-county travel by university students, and contradictory business closure measures).

Back-of-the-Envelope Estimates on “Breakthrough” Risks Associated with COVID-19

We probably know at least one family member or friend who is fully vaccinated and boosted, but who remains deeply concerned that they will still get COVID-19 from an unvaccinated person (i.e., a “breakthrough” case) and end up hospitalized or dead.

I certainly know someone who fits that profile. But is that an rational fear?

To allay this person’s anxiety, I sought out the best available U.S. data on the subject from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). While their aggregated “breakthrough” data only goes through November 2021 (therefore missing the impact of the Omicron variant), it is a good start for a rough estimate of the various COVID-19 risk probabilities for fully vaccinated people.

[The data I am using for this analysis is available here and here.]

Let us first estimate the chance of a fully vaccinated person getting COVID-19 over an entire year. According to the CDC, the week of August 28, 2021 saw a “breakthrough” rate of 117.74 cases per 100,000 vaccinated people in the 26 U.S. states that collect such information (the list of states can be found here). That is the highest weekly rate between April and November 2021 (the lowest being 4.96 per 100,000 during the week of June 5, 2021). To be conservative, I multiplied 117.74 by 52 weeks and divided 100,000 by that product, giving us an estimate of 1 in 16 that a fully vaccinated person will get COVID-19 over the next 12-month period.

That sounds about right. Vaccines aren’t perfect, but definitely effective. According to the CDC, an unvaccinated period has a five times greater chance on contracting COVID-19 than an vaccinated person.

What about hospitalizations? Using the same methodology, I took the CDC’s weekly hospitalization rate for fully vaccinated people (5.4 per 100,000 during the week of November 13, 2021), multiplied by 52 and divided 100,000 by that product to get this estimate: There is a 1 in 356 chance that a fully vaccinated person will be hospitalized for COVID-19 over the next 12-month period.

As a fully vaccinated person myself, I like those chances. The CDC estimates unvaccinated people have an eight times greater chance of being hospitalized for COVID-19.

Finally, the granddaddy of estimates: What are the chances a fully vaccinated person will die from COVID-19 over the next year? The CDC says, at its weekly peak between April and November last year, COVID-19 killed 1.03 vaccinated people per 100,000 vaccinated people. Multiplying that number by 52 and dividing 100,000 by that product, we get this estimate: There is a 1 in 1,867 chance that a fully vaccinated person will die from COVID-19 over the next 12-month period.

In my experience, I consider such chances basically the same as zero.

Some people, like Lloyd in Dumb and Dumber, may view probabilities differently…

But if we take that probability (1 in 1,867 each year) and extend over 60 years, we end up with a 1 in 31 chance that a fully vaccinated person will die from COVID-19 over a 60-year period. That is a 3 percent chance. Compare that to other lifetime probabilities: Dying in a car accident = 1 percent; dying of cancer = 15 percent; dying of heart disease = 17 percent.

Obviously, the lethality of COVID-19, the treatments for it, and the immunities that may build up within us to fight it off renders such a long-term estimate meaningless. But, the point remains, the chances of a vaccinated person dying from COVID-19 are exceedingly remote.

That doesn’t mean CNN won’t find those deadly “breakthrough” cases that do occur and try to scare the crap out of you.

There is irrationality on every side of the political spectrum

What is worse? Not getting vaccinated or harboring a grotesquely inaccurate understanding of the risk probabilities associated with COVID-19?

I think both pose serious problems. The unvaccinated potentially hurt themselves and those close to them who are also unvaccinated. There is also a small chance that other people will be denied ICU beds because they are occupied by unvaccinated COVID-19 patients.

But possessing an unwarranted fear of COVID-19 is equally dangerous and can also cause needless, even life-threatening, harm to others. Every time a state shuts down businesses and economic sectors due to surges in COVID-19, they are putting people out of work, a large number of whom cannot afford lapses in income and health insurance.

The wealth of the world’s wealthiest has surged during the COVID-19 pandemic, while millions of people worldwide have descended into poverty. This is not hyperbole. It is widely-accepted fact among economists. Furthermore, people can die when they become impoverished.

So, when the majority of Democrats hold irrational fears about the dangers of COVID-19, they increase the likelihood that politicians will pursue bad COVID-19 policies that may do more harm than good. People die when livelihoods are threatened and giving them a $2,000 check now and then is not enough to change that fact.

Whether from a left, right or center perspective, what is the solution to all of this? Stop watching, listening or reading the news from mainstream news outlets and seek alternative news sources (The Grayzone, Breaking Points, etc.). Perhaps then the national news outlets will consider hiring more trained journalists with backgrounds outside of our elite universities. I recommend University of Iowa journalism grads, but I’m biased.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: kroeger98@yahoo.com

To what extent did attitudes about Biden and Trump change during the 2020 general election?

By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; July 6, 2021)

“Our political opinions and attitudes are an important part of who we are and how we construct our identities. Hence, if I ask your opinion on health care, you will not only share it with me, but you will likely resist any of my attempts to persuade you of another point of view,” New York University psychologists Philip Pärnamets and Jay Van Bavel wrote in Scientific American in 2018.

Pärnamet, Van Bavel and their associates at Lund University in Sweden had previously found that manipulating a person’s opinions and attitudes is not as difficult as sometimes thought in today’s highly partisan environment, and once changed, these new opinions and attitudes can be surprisingly durable.

In their study, after giving study participants false-feedback on one of their opinions — for example, telling a participant they had indicated their opposition to raising taxes when, in fact, they had said they supported raising taxes — the researchers offered them a chance to give an argument for their “new” opinion without fearing they would be criticized for it. It turned out that the act of rationalizing this “new” belief in a non-judgmental context made it more durable over time.

“When it comes to the actual political attitudes we hold, we are considerably more flexible than we think,” according to New York University psychologists Philip Pärnamets and Jay Van Bavel. “People have a pretty high degree of flexibility about their political views once you strip away the things that normally make them defensive.”

In other words, remove a person’s feeling of needing to defend their ideas from criticism, they are more open to alternative ideas.

Conversely, unwillingly expose someone to an opposing opinion and they are likely to erect defensive barriers to it and, in turn, become more entrenched in their original belief. [I suspect that is the reason I lose a few Facebook friends every time I post a video excerpt from Tucker Carlson Tonight.]

This is good and well, but the dominant (non-Fox News) media narrative was that, after four years of a near constant drumbeat of negative news coverage, Trump’s popularity was near an historical low-point for an incumbent president and, subsequently, the vast majority of Americans had already made up their minds about him.

Axios’ Neal Rothschild laid out the facts supporting that narrative in a Sept. 2020 article:

A wealth of evidence suggests more Americans have made up their minds by this point compared with years past:

The conventions had practically no impact on the shape of the race: Biden’s national polling lead (+7.5 per FiveThirtyEight’s average of polls) is just a half-point smaller than it was a month ago.

Just 3% of likely voters said they didn’t know who they’d vote for in a recent national Quinnipiac poll. The same percent of registered voters said they were undecided in a Monmouth poll this week.

An August poll by the Pew Research Center found that among those who preferred Biden or Trump, just 5% said there was a chance they’d change their minds.

Compare that to Pew’s poll in August 2016, which found that 8% of Hillary Clinton’s supporters said there was a chance they might vote for Trump. Similarly, for those who preferred Trump, 8% said they might vote for Clinton.

Even in the swingiest of swing states, most people’s minds appear made up. Just 5% of Floridians say they might change their minds, according to a recent Quinnipiac poll.

Political scientists happily concurred with the ‘set in stone’ narrative heading into the 2020 general election. “There were Republicans who were undecided in 2016 but ultimately rallied to Trump,” John Sides, a political science professor at Vanderbilt, told Axios. “This year, they’re likely on board. And, if not, they jumped ship a while back.”

Rothschild and Sides were justified in their conclusions, but still wrong in the bigger picture.

To what extent did attitudes about the 2020 presidential candidates change?

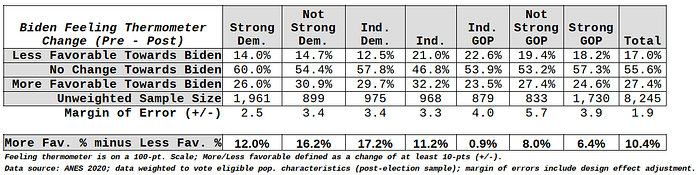

Data from the 2020 American National Election Study (ANES), conducted in two waves (pre- and post-election) between August and December 2020, confirm significant numbers of vote eligible Americans changed their opinions about the two major presidential candidates during the course of the general election.

Enough that it could have changed the final outcome? Probably not. Nonetheless, it is inaccurate to suggest, even in today’s highly partisan political environment, that attitudes about Biden or Trump were largely ‘set in stone’ before Election Day.

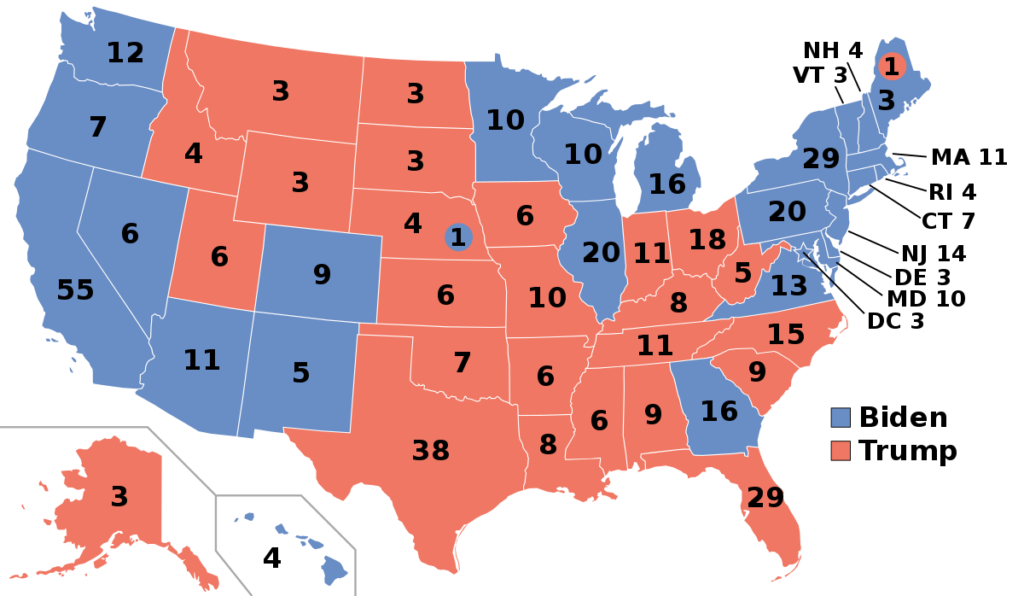

For starters, one-third of eligible voters changed their favorability rating of Trump by at least 10-points (on a 100-point scale) during the course of the general election. [The text of the ANES 2020 thermometer favorability questions are in the Appendix A.]

Among Strong Republicans, 24 percent of respondents became less favorable towards Trump during the campaign. That translates to 11.5 million Strong Republicans — three million of whom either voted for Biden (660,000) or did not vote (2.3 million!). These are potentially election outcome changing numbers, especially when an outcome change in just four closely contested states would have changed the Electoral College outcome.

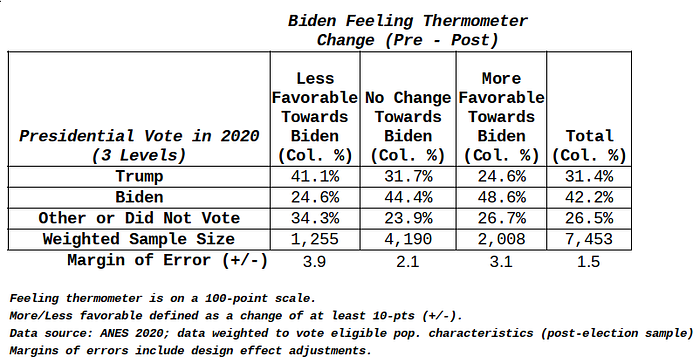

Tables 1a and 1b (below) show the percentage of vote eligible Americans that changed their favorability rating by at least 10-points for Joe Biden and Trump between the general election and the post-election period.

For example, among Strong Democrats, 14 percent of ANES 2020 voters reported lower favorability ratings for Biden between the general election and post-election period, while 26 percent increased their favorability rating for him. Sixty percent reported no change in their favorability rating of Biden. Weak (‘Not Strong’) Democrats and Independents leaning-Democrat were similarly inclined to upgrade Biden.

More importantly, the percentage of Independents who upgraded Biden was significantly higher than those who downgraded him (32% versus 21%).

Among Republicans, no significant difference existed between the percentage of those who upgraded or downgraded Biden between the pre- and post-election periods.

Overall, 44 percent of eligible voters changed their favorability rating of Biden between the pre- and post-election ANES 2020 surveys.

Table 1a. Biden Favorability Change (Pre- to Post-Election)

Table 1b. Trump Favorability Change (Pre- to Post-Election)

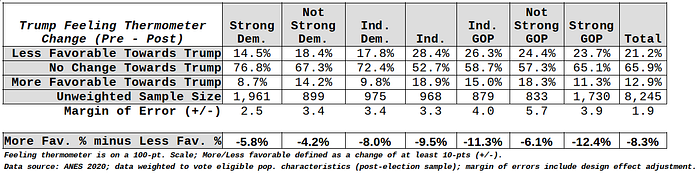

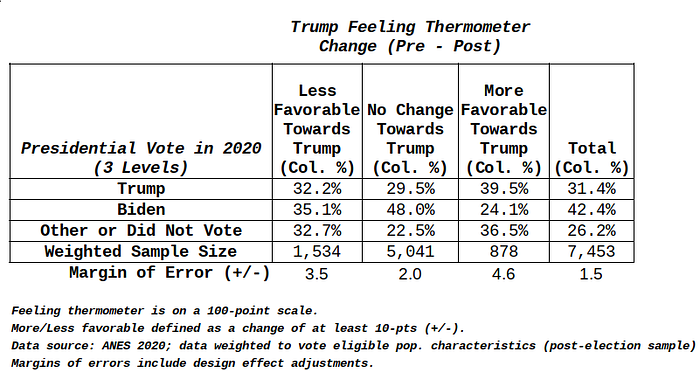

The pattern for Trump was quite different.

Across all party identification groups — with the exception of Weak (‘Not Strong’) Republicans and Weak (‘Not Strong’) Democrats — all partisan groups experienced a higher percentage of respondents who downgraded Trump versus those who upgraded him. For example, among Independents, 28 percent lowered their favorability towards Trump, while only 19 percent increased it.

Overall, 66 percent of eligible voters did not change their view about Trump over the course of the 2020 presidential campaign, compared to only 56 percent for Biden.

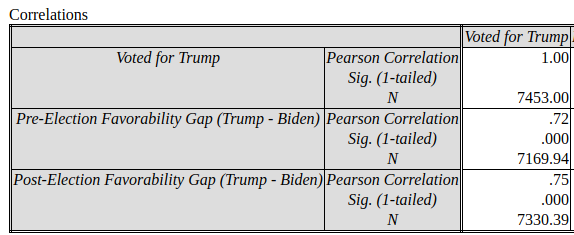

For many possible reasons, Biden plainly increased his favorability advantage over Trump during the 2020 general election (see Table 2a) and this advantage was significantly correlated with final vote choices (see Table 2b).

Table 2a. Mean Levels and Mean Changes in Candidate Favorability (100-point scale)

Table 2b. Correlation between Favorability Rating Gaps and 2020 Vote Choice

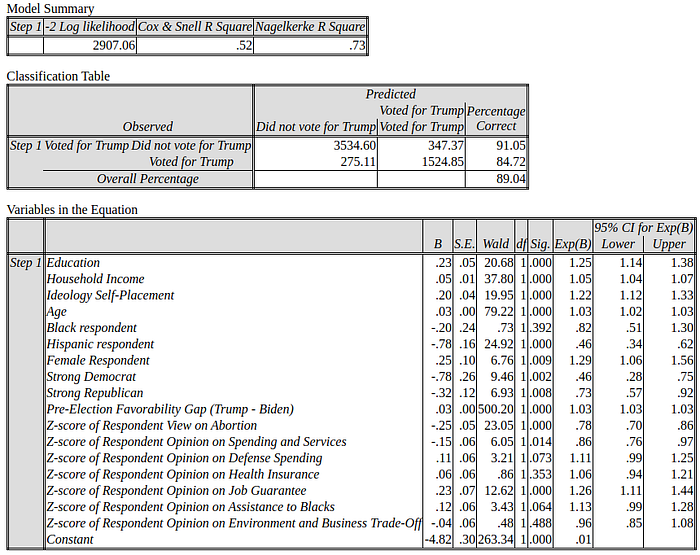

Even after controlling for key demographic characteristics (age, education, income, race, sex), party identification, political ideology, and policy attitudes (abortion, health care, job guarantee, social spending, defense spending, and environment), the favorability gap between Trump and Biden was the strongest predictor of vote choice (see in Appendix B a preliminary logistic model of the 2020 presidential vote choice).

Trump failed to tarnish Biden

A methodological note is required before moving forward…

The ANES 2020 post-election favorability question was asked after the actual election. Subsequently, how a respondent answered that question was potentially impacted by the outcome of the election. It is, therefore, dubious to draw any conclusion about the impact of a change in candidate favorability on how people voted. Our predictor variable (change in favorability ratings) is contaminated by the outcome variable (vote choice).

Nonetheless, the relationship between those two variables is informative. Tables 3a and 3b show the relationship between changes in the Biden and Trump thermometer ratings and 2020 vote choices.

In Table 3a, among the largest thermometer change group (No Change Towards Biden), 44 percent voted for Biden, compared to only 32 percent for Trump. Conversely, among those who indicated no change in favorability towards Trump, 30 percent voted for Trump, compared to 48 percent who voted for Biden (see Table 3b).

Table 3a. Biden Favorability Change (Pre- to Post-Election) by 2020 Vote Choice

Table 3b. TrumpFavorability Change (Pre- to Post-Election) by 2020 Vote Choice

The status quo was in Biden’s favor. But what about among voters who increased their rating of Biden between the pre- and post-election periods?

Forty-nine percent of respondents who increased their rating for Biden also voted for him, compared to only 25 percent who voted for Trump — that is a 24-point gap (see Table 3a).

In contrast, 40 percent of respondents who increased their rating for Trump also voted for him, compared to 24 percent who voted for Biden — that is a 16-point gap (see Table 3b). In that same group, 37 percent did not vote for president — the highest non-voting rate among the thermometer rating change groups.

Among respondents who lowered their view of Trump during the general election, there was no significant vote share difference between Trump and Biden (32% versus 35%, respectively). Put differently, beating Trump down did not change many votes. Instead, Biden’s victory was built on the back of a status quo environment already in his favor (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic, a weakened economy) and a general election campaign that generated additional positive feelings towards him.

The Trump campaign and Republican Party failed to convince the American voting public to dislike Biden, and it wasn’t for a lack of trying.

It is hard to see the resiliency of Biden’s popularity and not think the news media played a critical role. In a previous essay, I detailed the overwhelming advantage in tone Biden had over Trump in online news coverage during the 2020 election.

But were there any particular TV news programs disproportionately associated with Americans who changed their opinions of Biden and Trump during the campaign? Fortunately, the ANES 2020 asked respondents which TV news programs they watched regularly (question text is in Appendix A) and offers at least a preliminary look at that question.

Did some news shows matter more than others in 2020?

Quantifying media effects in political campaigns has been one of the holy grail quests of political scientists for decades. And, typically, when positive results have been found, the research has required tightly-controlled experimental designs and idealized research settings. The challenge in finding consistent, strong media effects in political campaigns is partly the result of two real-world challenges.

First, there is a mammoth selection bias problem. People do not choose their media sources randomly. The factors that drive their selection of news shows also drive their preferences for political candidates. Furthermore, we don’t have a Walter Cronkite who can suddenly voice disillusionment with the Vietnam War and bring millions of Americans along with him. Anything Rachel Maddow says on her show, her audience is most likely already with her.

Second, virtually every potential voter consumes information derived from the news media. Voters are awash in news and information. Trying to determine if a voter’s opinions are affected by the news media is akin to wondering if a fish likes water.

Despite the methodological hurdles, the ANES 2020 data does show some interesting (while admittedly small) associations in TV news program preferences and changes in 2020 candidate favorability ratings. And while these associations don’t hold up when controlling for other factors (demographics, party id, policy attitudes, etc.), the bivariate relationships show some intriguing patterns.

Table 4 shows the relationship between a change in Biden or Trump favorability and TV news programs regularly viewed. Only statistically significant associations (chi-square statistic) are indicated, either by a (+) indicating a positive association, or a (-) indicating a negative association.

For example, regular viewers of Stephen Colbert’s Late Night were more likely to have their favorability towards Trump go unchanged during the campaign, and less likely to have become more favorable towards Trump. The net effect of Late Night’s continual bashing of Trump seemed to be in enforcing status quo opinion.

Table 4. Change in Biden/Trump Favorability by Regular Viewers of Selected News Programs (Pre- versus Post-Election)

For every news programs demonstrating significant associations with Biden or Trump favorability, the association was positively related to “no opinion change.” In fact, the only positive relationship with a change in candidate favorability was between people who became more favorable towards Trump and do not watch TV news programs regularly (see bottom-right corner of Table 4).

My interpretation: To the extent individual TV news programs matter at all in elections, it is in attracting viewers who are already less inclined to change their opinions about candidates. TV news programs enforce partisan alignments and are not independent, unbiased sources for news and information.

Final Thoughts

If ever there was going to be an election where the outcome was ‘set in stone’ long before Election Day, it would have been the 2020 presidential election.

In reality, there was significant opinion change among eligible voters towards Biden and Trump in the 2020 general election, despite a relentless effort by the mainstream news media to dampen such behavior.

Research by Swedish psychologists Pärnamets and Van Bavel mentioned at the beginning of this essay has been focused on changes in policy attitudes, not candidate support, but their conclusions concerning the former are likely relevant to the latter:

“…we need rethink what it means to hold an attitude. If we become aware that our political attitudes are not set in stone, it might become easier for us to seek out information that might change them.

There is no quick fix to the current polarization and inter-party conflict tearing apart this country and many others. But understanding and embracing the fluid nature of our beliefs, might reduce the temptation to grandstand about our political opinions. Instead humility might again find a place in our political lives.”

Amen.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: kroeger98@yahoo.com

Appendix A:

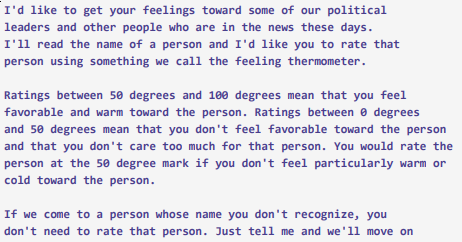

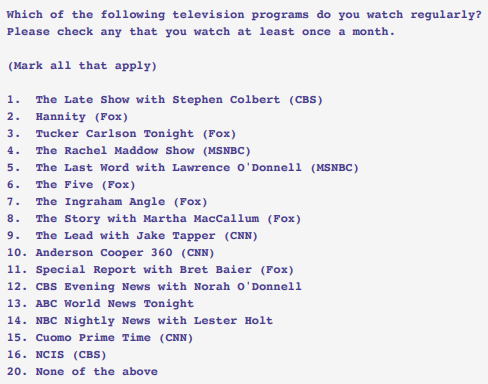

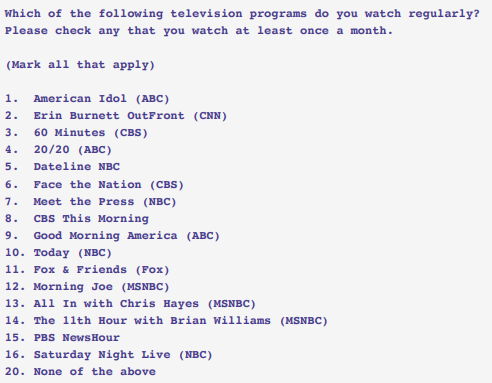

Key Questions from ANES 2020

Pre-election Favorability Question:

Post-election Favorability Question:

TV Show Viewing Question:

Appendix B:

Preliminary Logistic Model of 2020 Vote Choice

The news media too often serve up elite opinion instead of reality

By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, June 25, 2021)

In his classic 1984 Duke Law Journal essay, The Marketplace of Ideas: A Legitimizing Myth, Law Professor Stanley Ingber described the news and information landscape within the U.S. in ways easily applied to today:

“In our complex society, affected by both sophisticated communication technology and unequal allocations of resources and skills, the marketplace’s inevitable bias supports entrenched power structures or ideologies. Most reform proposals do little to help the marketplace reach its theoretical potential. Instead, such suggestions perpetuate the marketplace’s status quo bias or result in unacceptable levels of governmental interference and regulation.” (p. 85–86)

But Ingber’s view of our information ecosystem doesn’t require a conspiracy among economic and political elites to explain its biased effects:

“…the New Left presumed that this effect resulted from a conspiracy of established groups. Their view of the system as a construct of devious, manipulating elites seems overly simplistic. The elites need not consciously create and impose a system in order to benefit from it. The bias or skew toward established groups and dominant value perspectives instead may be unavoidable in a high-technology society in which resources and skills are distributed unequally.” (p. 85)

To Ingber, inequities in what facts, ideas and opinions most prominently make it into the information bloodstream stem from systemic inequities, not the coordinated actions of a small cadre of elites — which is why he dismisses popular freedom of speech reforms, such as The Fairness Doctrine and federal election campaign laws, that he said “easily could decay into formal systems of governmental censorship or popular indoctrination.”

“If we intend to design a social and political system open to the development of diverse perspectives and values, we must first understand how an idea initially outside the community agenda of alternatives becomes accepted within it.” (p. 86)

While Ingber rejects leftist assumptions that the system is the product of “devious, manipulating elites,” he may have been equally naive in believing powerful interests don’t have a demonstrable, independent impact on existing imbalances on what information gets promulgated within the mainstream news media. Nonetheless, Ingber’s analysis from 40 years ago remains brutally relevant to today.

Ingber argued some legitimate perspectives, outside mainstream thought, are denied access to a sizable audience because of structural barriers within the system.

In rare instances, such as when ecological realities profoundly change — like in the Great Depression or the Vietnam War — do novel perspectives become integrated into the mainstream discourse, according to Ingber. “There is little doubt that a change in the ecological setting necessarily creates new interests and needs which in turn alter perspectives,” he wrote.

So we must wait until the next great economic recession or counterproductive U.S. military intervention to see substantive changes in status quo thinking? Ingber offers another path:

“In addition to ecological change, new perspectives and values may be nurtured in a society that encourages, or at least permits, the development of new interests and experiences. Consequently, the status quo bias of the marketplace can probably be neutralized only by protecting a greater liberty of action — allowing people to choose among lifestyles offering differing roles and relationships — rather than merely supporting the freedom of speech.”

Homogeneous sourcing: A case study using a New York Times story on ISIS in Africa.

At the heart of the Ingber argument is that a diversity of perspectives is critical to minimizing the ‘status quo bias’ of the marketplace of ideas: An informed, free-thinking society, empowered by experiential diversity, is capable of navigating contradictory ideas (including falsehoods) when given the necessary information needed to weigh them against one another.

Ingber’s 1984 essay came to my mind recently as I waded through hundreds of news articles about the alleged growing strength of jihadists on the African continent — articles like the following:

ISIS attacks surge in Africa even as Trump boasts of a ‘100-percent’ defeated caliphate (Washington Post, October 18, 2020)

Is Africa overtaking the Middle East as the new jihadist battleground? (BBC, December 3, 2020)

In bid to boost its profile, ISIS turns to Africa’s militants (New York Times, April 7, 2021)

With few exceptions, these articles and many others like them rely heavily on official government sources and U.S./European-centric think tank analysts, who, by training and financial support, back a common thesis: Islamic extremists are turning to Africa to continue and expand their war against Western institutions and influence.

Keep in mind, we are talking about a continent with over 1.2 billion people (of whom 44 percent are Muslim), and more racial/ethnic/genetic diversity than any other continent on the planet. Almost any hypothesis regarding Islam can find anecdotal support somewhere within its vast geography.

On one hand, Islamic jihadists are on the rise (Ansar Dine in Mali) ; and, on the other, Islam and democracy are not antithetical (Tunisia).

Africa and Islam are too complex to summarize in pithy headlines.

And, yet, that is exactly what our most prestigious news organizations do every day, and they do so while generally depending on a relatively narrow range of sources and perspectives.

As anecdotal evidence, we have the April 7th New York Times article, by Christina Goldbaum and Eric Schmitt, which included these sources:

(1) The Soufan Group — a New York-based security consulting firm founded by an ex-FBI interrogator— Ali Soufan — and highly regarded within the U.S. national security establishment,

(2) Africa Center for Strategic Studies — a U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) research institute,

(3) Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS — a U.S. State Department-organized coalition of 80 nations opposed to ISIS,

(4) ExTrac — a private, data-driven intelligence service (based in the U.S.) which combines “real-time attack and communications data with artificial intelligence (AI) to provide actionable insights for counterterrorism and Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) policymakers and practitioners,”

(5) The International Crisis Group — a non-profit, non-governmental organization used by policymakers and academics “working to prevent wars and shape policies that will build a more peaceful world,” though described by journalist Tom Hazeldine as a group that “consistently championed NATO’s wars to fulsome transatlantic praise,”

(6) Mozambican Research Institute (Observatory of Rural Areas) — a Mozambican non-governmental organization that aims to contribute to the sustainable development of Mozambique’s rural regions,

(7) “Experts and officials in the U.S. and Europe,”

(8) “American and United Nations counterterrorism officials.”

These aren’t necessarily disreputable or dishonest sources for knowledge about Islamic State (IS)-related militant activities in Africa, but they are demonstrably linked to the U.S.-European security and foreign policy establishment — with the exception of the Mozambican Research Institute, which was one of the few sources in the Times article saying Islamic State jihadists are not well-liked among rural Mozambicans.

Most of the Times’ sources represent a bounded range of viewpoints on the strength of Islamic militants in Mozambique and the continent overall. To the Times’ credit, alternative viewpoints were elicited in their story — the problem is that it took until the 30th paragraph in a 36-paragraph story to hear them:

“People in Cabo Delgado (Mozambique) have come to realize this group is not a solution, it’s destroying the local economy and it’s become very, very violent with the population,” said João Feijó, a researcher at the Mozambican Observatory of Rural Areas. “Nowadays the group is pretty isolated.”

That represents status quo journalism in a nutshell: Rely almost entirely on establishment sources and declare the story balanced because an alternative opinion was cited somewhere near the end of the story.

It is not a conspiracy — it is merely the result of journalists taking the path of least resistance by emphasizing expediency and ‘what is publishable’ over healthy intellectual curiosity.

What should international affairs journalists be doing instead? My answer would be something told to me in my first journalism class by the late Hanno Hardt, Professor Emeritus in the University of Iowa’s School of Journalism and Mass Communication:

Seek as many points of view as necessary to tell the whole story.

The Times story on the Islamic State in Mozambique or the other ‘rise of IS in Africa’ articles, all offer one dominant perspective — that of the U.S.-European defense and security community.

However, scratch the surface of this narrative — Islamic extremism is rising in Africa and the U.S. and Europe must somehow intervene — and the story becomes more complicated and less open to easy solutions.

We can start by looking at overall trends…

A little data sheds a lot of light on African violence

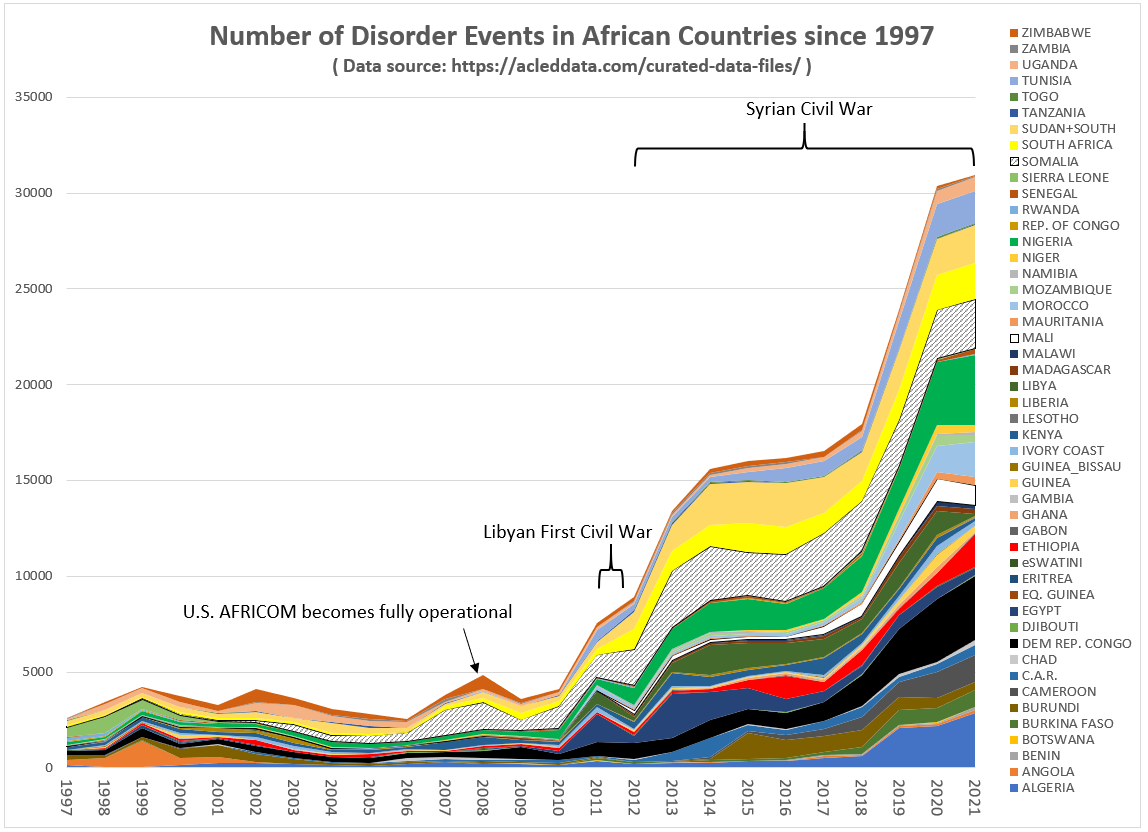

Figure 1 shows the number of disorder events occurring in Africa since 1997, according to The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), a widely used real-time data and analysis source on political violence and protest around the world.

The topline finding is that violence is on the rise in Africa and it is happening in more than Muslim-majority or near-majority countries — it is happening throughout the continent.

Figure 1: Disorder events in African countries since 1997

Not as easily discernible in the above time-series graph, however, is what may be causing this surge in violence.

Here are some initial thoughts…

There is academic research and strong anecdotal evidence that the aftermath of the Libyan and Syrian civil wars played a significant role in the timing and spread of this violence in Africa.

One of the first and largest year-to-year increases in African violence (i.e., disorder events) occurred from 2010 to 2011, which coincides with a series of key events in north Africa and the Middle East: (1)The Arab Spring, beginning with protests in Tunisia on December 18, 2010 in Sidi Bouzid, (2) the practical end of the U.S. occupation of Iraq, (3) the start and end of the First Libyan Civil War, and (4) the start of the (still on-going) Syrian Civil War.

The significant year-to-year rise in African violence continues until it tapers off in 2015 and remains relatively constant through 2017, when it starts to dramatically increase again in 2018 — the year after Bashar al-Assad’s government forces in Syria, with the help of Russia and Iran, finally gained the upper hand against the Islamic State (ISIS) and other jihadist forces, leading to a reduction in violence across most of the country, and prompting some jihadists to leave Syria to go home or join other conflicts (e.g., Afghanistan).

Through the first five months of 2021, five African countries — Nigeria, Dem. Rep. of Congo (DRC), Algeria, Somalia, and South Africa — account for nearly half (46%) of all disruptive events on the continent, according to ACLED, of which two are predominately Christian countries (DRC and South Africa).

It does not minimize the present threat of Islamic extremists in Africa (which is real) to acknowledge that a significant amount of the current violence is not related to Islam. And where Islamic extremism is the issue, it is fair to recognize that Western powers played a crucial role in events leading up to Islamic extremism’s rise in Africa.

The Arab Spring in Africa’s Maghreb and the First Libyan Civil War

A common conclusion among Western analysts about rising African violence is that it is partially a byproduct of ISIS’ defeat in Syria, 2011’s Arab Spring, and the return home of foreign fighters from Libya’s First Civil War.

Let us start with the first point…

To what extent did ISIS fighters in Syria end up in Africa? An exact number is impossible to determine — and there was reporting suggesting it was smaller than anticipated — but there were notable Islamic extremist attacks in northern Africa in 2018 and 2019, including a December 26, 2018 bombing of Libya’s foreign ministry, and a January 17, 2019 raid in northeastern Nigeria. And, more recently, an horrific jihadist attack killing 130 people in Burkina Faso further highlights the presence of jihadist ideology in northern Africa.

The ACLED data on African violence in Figure 1 is also illuminating on how the 2011 Arab Spring, along withthe end of the First Libyan Civil War in that same year, may have impacted subsequent violence in Africa’s Sahel region.

According to the ACLED data, in 2011, the Arab Spring saw the number of disorder events increase exponentially in Muslim-majority countries of Algeria (+187%), Libya (+13,220%), Morocco (+1,300%), and Tunisia (+1,964%).

However, the real story may be how violence spread into Africa’s Sahel after the fall of Col. Muammar al-Gaddafi’s Libyan regime in October 2011, when foreign fighters, who had been supporting Gaddafi’s government forces, joined other militant movements or returned to their home countries, well-armed, relatively well-trained and unemployed.

In 2012, of the 12 nations making up the Sahel, nine saw a significant increase in disorder events: Central African Repubic (+90%), Chad (+33%), Ethiopia (+94%), Mali (+923%), Mauritania (+143%), (Nigeria (+161%), Senegal (+83%), South Sudan (+291%), and Sudan (+120%). The three Sahel countries that didn’t see significant rises in violence in 2012 (Burkina Faso, Eritrea, and Niger) did experience increases in 2011 (Burkina Faso and Eritrea) or in 2013 (Niger).

But while most of the Sahel violence has occurred in Muslim-majority countries and many of the rebel groups involved, such as Mali’s militant Islamist sect Ansar Dine, are ideologically linked to al-Qaeda or ISIS, it would be a mistake to assume this rise in violence is only rooted in an Islam versus the Secular World paradigm. In fact, among the 19 African countries with the largest Christian majorities (70 percent+) and Muslims representing less than 20 percent of the population, 13 witnessed significant increases in disorder events in 2011 and 2012 (Angola, Botswana, Democratic Republic of Congo, eSwatini, Gabon, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe).

Along with Islamic State and al-Qaeda aligned militant groups, Africa has a significant number of non-Islamic rebel movements: the Lord’s Resistance Army in Sudan and South Sudan, The Cabinda State Liberation Front (FLEC) in Angola, the Coalition of Patriots for Change in the Central African Republic, and the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (NMLA) in Mali, to name just a few. The NMLA is particularly interesting in that its manpower and firepower increased substantially after the fall of Gaddafi’s Libya and the return to Mali of ethnic Taureg’s who had fought in that conflict.

Violence is rising throughout Africa. That is a fact. As to its sources, any causal model depending solely on the proximate role of Islamic jihadists fails to consider other important factors. Furthermore, it is somewhat laughable to presume there is a “model” that can reliably explain violence (disruptive events) for an entire continent of 1.2 billion people.

Nonetheless, the exercise in trying to build such a model is worthwhile, even if a bit futile in the end.

Possible factors in the rise of violence in Africa

ISIS and other Islamic extremist groups: ISIS is no doubt part of Africa’s violent mix, particularly in northern Africa. But is this marginally cohesive organization really the threat to stability on the African continent, an extraordinarily big place with more linguistic, religious and genetic diversity than any other continent in the world? Considering Sunni jihadist groups have, in the past, been highly dependent on financial support from countries like Saudi Arabia and Qatar, is it perhaps short-sighted to focus on a symptom (such as the Islamic State) rather than a root cause (the Saudi funding and promotion of Sunni Wahhabism)?

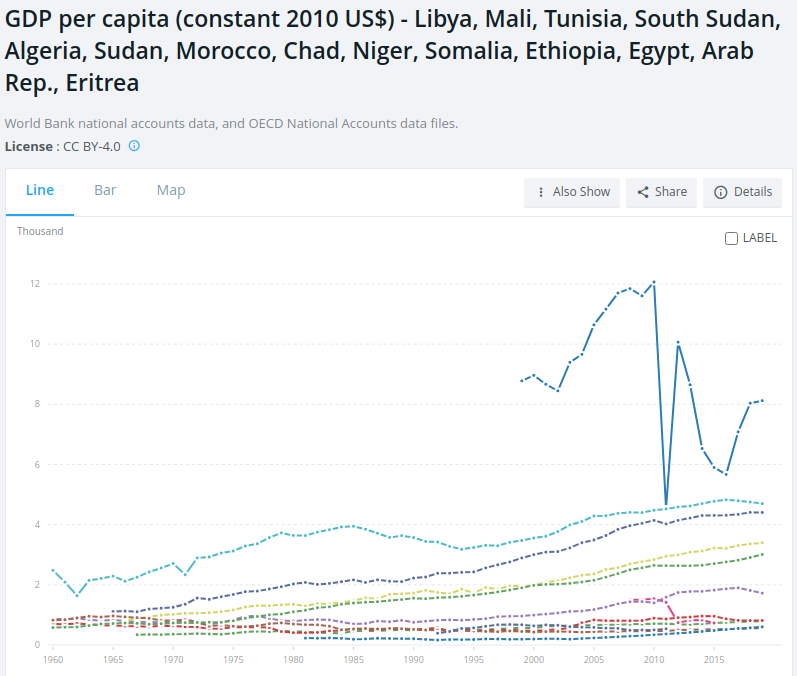

U.S. and European interventions: It is also defensible to recognize the role U.S.-European interference in creating African instability. Academics and analysts have documented the contribution of Libya’s post-Gaddafi instability to the weaponizing of rebel groups in northern Africa and subsequent rises in violence. Once one of the wealthiest African nations prior to NATO’s coordinated military effort to destabilize Gaddafi’s government, the Libyan economy was shattered after his fall (see Figure 2 below where the top line tracks Libya’s GDP per capita since 1999), which had a direct impact on Libya’s poorer neighbors whose economies partially depended on monetary influxes from Libya.

Figure 2: GDP per capita for Libya and selected north African countries over time

In addition, French military operations in Mali since 2013 (such as Operation Serval and Operation Barkhane) have not stopped Islamic jihadists from gaining control of much of northern Mali and a growing resistance from the Mali populace to the French military presence in general.

Any argument supporting U.S.-European interventions in Africa must contend with the reality that such interventions have a checkered record in terms of bringing stability — and that is probably too generous an assessment.

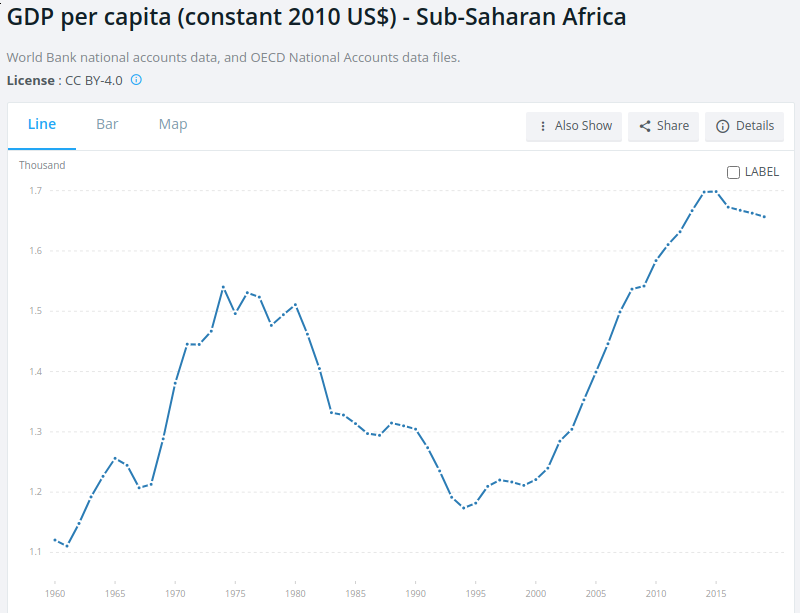

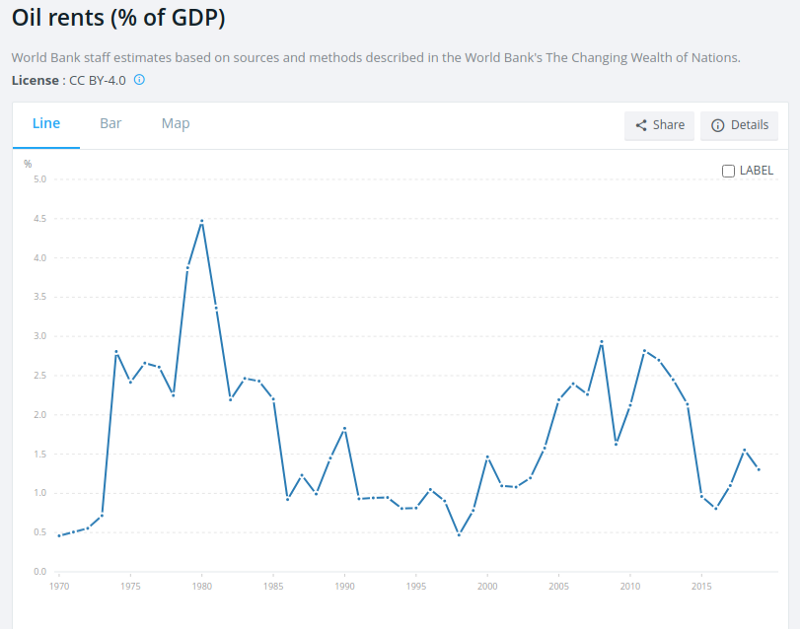

Falling oil prices and economic stagnation: The first 15 years of the 21st-century witnessed an historic economic boom in sub-Saharan Africa, with GDP per capita rising over 42 percent (see Figure 3). At the same time, a relative surge in oil prices also contributed to economic prosperity in oil-producing countries like Libya and Nigeria (see Figure 4).

Figure 3: GDP per capita in Sub-Saharan Africa since 1960

Figure 4: Oil rents (as a % of GDP) since 1970

Unfortunately, the African economies stagnated after 2011, in part due to falling commodity prices and, more generally, the weakened world economy that followed the 2008 world financial crisis.

Quantitative research on political violence and insurgencies has consistently found economic deprivation plays a significant role in the ability of militant groups to recruit soldiers and popularize their movement within a population, particularly when in the midst of local and regional economic inequities and weak political institutions.

In their influential research paper, Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War, Stanford political scientists James D. Fearon and David D. Laitin, who analyzed 161 countries between 1945 and 1999, concluded that:

The factors that explain which countries have been at risk for civil war are not their ethnic or religious characteristics but rather the conditions that favor insurgency. These include poverty-which marks financially and bureaucratically weak states and also favors rebel recruitment-political instability, rough terrain, and large populations.

More recent cross-national research, focused on Sub-Saharan African countries between 1986 and 2004, concluded that the onset of civil conflict is more likely in regions with (1) low-levels of education, (2) strong relative economic deprivation, (3) strong intraregional inequalities, and (4) the combined presence of natural resources and relative deprivation.

Even 2013 research on Boko Haram, a Nigerian Islamist group, by the quasi-governmental U.S. Institute of Peace concluded that: “Poverty, unemployment, illiteracy, and weak family structures make or contribute to making young men vulnerable to radicalization. Itinerant preachers capitalize on the situation by preaching an extreme version of religious teachings and conveying a narrative of the government as weak and corrupt. Armed groups such as Boko Haram can then recruit and train youth for activities ranging from errand running to suicide bombings.”

Striking throughout the quantitative literature on civil wars and regional insurgencies is the lack of significance among ethnic and religious variables in explaining the outbreak of violence.

Contrary to the security establishment sources in the Times article who argue that U.S.-European military support is essential to stemming the rise of militant Islam in Africa, a broader, more objective canvass of sources would have found as many experts arguing the most effective approach to ending the violence would be for increased investments in education, infrastructure, poverty alleviation and good governance initiatives by African governments.

Both arguments can be true, of course. But one would never know that such a contrast in solutions existed if all one had was the New York Times to rely on.

Final Thoughts

In previous posts I’ve lamented the many blind spots that seem to define mainstream journalism today. More disturbing (to me) is the propensity of the national news media to uncritically repeat the opinions of the U.S. national security industry.

If you want to understand why elite media organizations like the New York Times or Washington Post can get so many stories wrong, just look at the sources they continuously canvass for quotes (not to mention their documented willingness to use other journalists as “independent” sources).

How is it possible that the most prestigious, best paid journalists in the U.S. get so many stories utterly wrong?

Nowhere is this problem more apparent than news coverage of international affairs when news organizations incestuously recirculate the same quotes from the monolithic U.S.-European think tank brigade — an insular cadre of career policy analysts and former defense and intelligence officials from places like the Council on Foreign Relations, Human Rights Watch, The Brookings Institute, American Enterprise Institute, Center for American Progress and the Center for Strategic and International Studies — or when they lazily depend on anonymous “intelligence sources” and nameless government officials.

The last place to go for an objective analysis of African defense and security issues are these aforementioned sources. Yet, that is the source of most all mainstream reporting on the topic.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: kroeger98@yahoo.com

The inconvenient truth about prejudice and racism in the U.S.

By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; May 10, 2021

“If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it.” — Peter Drucker

“One can ignore reality, but one cannot ignore the consequences of ignoring reality.”— Ayn Rand

Since my days as a young grad assistant in the late 1980s, I have periodically worked in and around the social science debate on the best methods for measuring racist attitudes and behaviors in the U.S.

With respect to racial attitudes, in particular, I have encountered two main schools of thought. The first school believes we can ask people directly about their feelings on race and ethnicity and receive substantively unbiased answers (in the statistical sense of bias). While people are capable of hiding their true feelings on sensitive subjects (i.e., the social desirability bias), if the research study is well-designed and protects anonymity, people will answer questions on socially sensitive issues with surprising honesty, according to this school of thought.

The second school is not as sanguine. In their view, people are captive to their desire to leave a favorable impression with others and will try to avoid being classified as a ‘racist’ or ‘bigot.’ Thus, people will modify their responses on opinion surveys regarding racial attitudes to avoid such pejorative labels. In other words, researchers can’t simply ask people what they think on race, but must employ indirect methods for assessing an individual’s true racial attitudes (such as randomized response techniques).

While I am sensitive to the concerns of the second school, in practice I have found simple, direct questions on race and ethnicity to consistently reveal substantive differences in racial attitudes among U.S. adults. [An excellent research summary on these two school of thoughts can be found here. I also covered this research controversy in a previous Medium.com essay.]

With this caveat in mind, here are results from one of the latest research studies on U.S. attitudes regarding race and ethnicity, collected by researchers from Stanford University and the University of Michigan in the 2020 American National Election Study (ANES).

Racist attitudes are not just a Republican problem

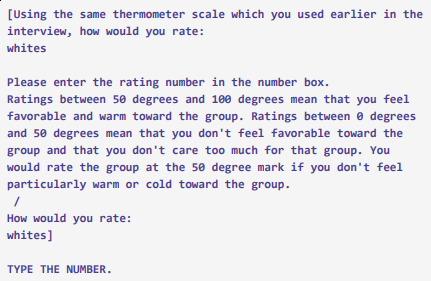

The 2020 ANES administered a series of thermometer scales (0 to 100) to assess respondents’ favorability towards four specific race and ethnic groups (Whites, Blacks, Hispanics and Asians):

How does someone answer a question like this if they consciously refuse to judge anyone based on their race or ethnicity? As it turns out, about 15 percent of all respondents (out of 7,453 respondents to the post-election wave of the 2020 ANES) rated the four racial and ethnic groups as a ‘50.’ Some other respondents rated the four groups as equal at a different point on the scale. For example, nine percent of respondents rated all four groups a ‘100’. [Eight people rated each of the four race and ethnic groups a ‘0’!]

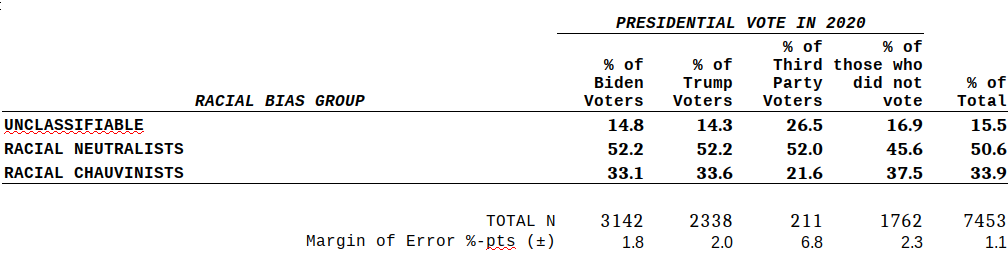

In total, 51 percent of U.S. eligible voters rated their own race/ethnicity as equal (or below) the other three race and ethnic groups (I label these respondents as “Racial Neutralists”). Another 34 percent of eligible voters rate their race or ethnic group higher than at least one other race or ethnic group (I label them “Racial Chauvinists”).

Lastly, an additional 16 percent of respondents either refused to answer the race/ethnicity favorability question for their own race/ethnic group or were from a race/ethnic group (e.g., Native American and multi-race respondents) where favorability ratings for their group were not asked (I label these respondents as “Unclassifiable”).

The number that seems to shock those I’ve shared this data with is the 34 percent of U.S. eligible voters who openly admit they harbor some level of racial or ethnic bias.

My wife’s initial reaction was to say, “They must be Trump Republicans.” — a reaction that was not unique. After analyzing 100 30-second news clips broadcast on CNN and MSNBC between May 1, 2020 and May 1, 2021 (the GDELT-archived clips can be found here), every single one explicitly connected racism to either Donald Trump supporters, conservatives, Republicans or white supremacists within those groups.

Is racism, in fact, mostly a Republican or white conservative problem?

Well, it depends on how you define mostly.

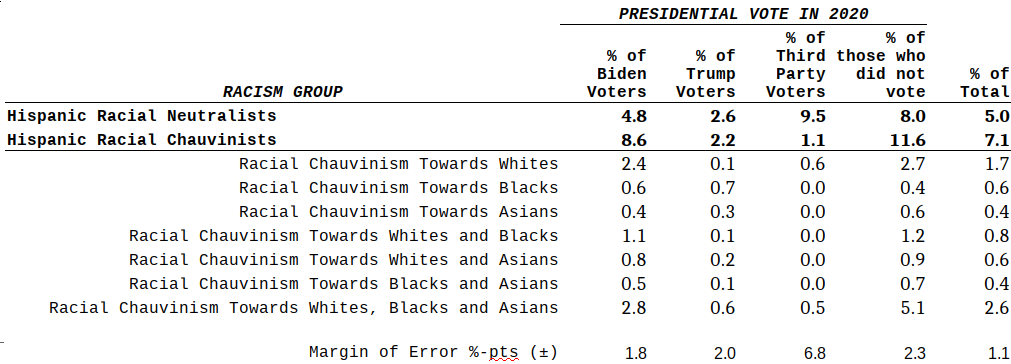

As Figure 1 shows, the percentage of racial chauvinists isbasically identical within the Biden and Trump voter bases (33.1 percent and 33.6 percent, respectively). Likewise, slightly over half of Biden and Trump voters can be categorized as racial neutralists. In contrast, third party voters are significantly less likely to be racial chauvinists (21.6 percent).

Figure 1: Racial/ethnic bias within the 2020 U.S. electorate (by presidential candidate)

How can that be true? Did the Trump voters lie on the ANES survey?

Relax my resistance friends. The news isn’t entirely positive for Trump Republicans.

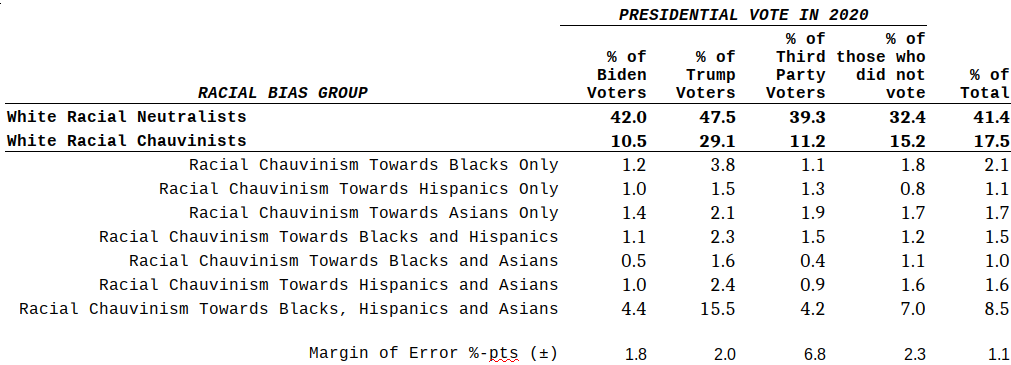

If we examine the 2020 electorate by their race/ethnicity, a more familiar picture of racial bias emerges. Figure 2 indicates that 29.1 percent of Trump voters are white racial chauvinists (i.e., rated Blacks, Hispanics, and/or Asians below Whites on a 100-pt. favorability scale), compared to only 10.5 percent of Biden voters. In other words, Trump voters are three times more likely than Biden voters to be white and a racial chauvinist.

At the same time, Biden and Trump voters are equally likely to be white and a racial neutralist (42.0 percent and 47.5 percent, respectively). That is to say, if you were to randomly draw one Trump voter and one Biden voter from their respective populations, you would have an equal chance in each case of drawing a white person with no (self-reported) racial bias.

Figure 2: Racial/ethnic bias within the 2020 U.S. electorate (by presidential candidate and eligible voter’s race/ethnicity)

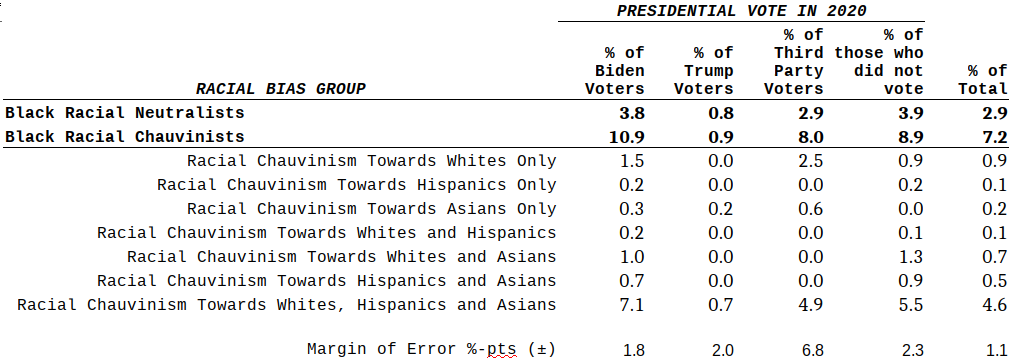

So, while a Trump voter is significantly more likely to be a white racial chauvinist than a Biden voter, when one adds the Black, Hispanic and Asian voters who are racial chauvinists to the mix, the percentage of Biden voters who are racial chauvinists turns out to be virtually the same as for Trump voters (i.e., about one-third).

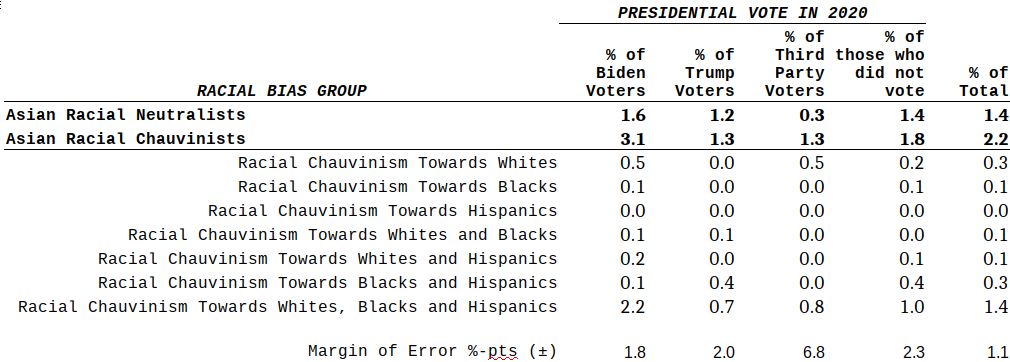

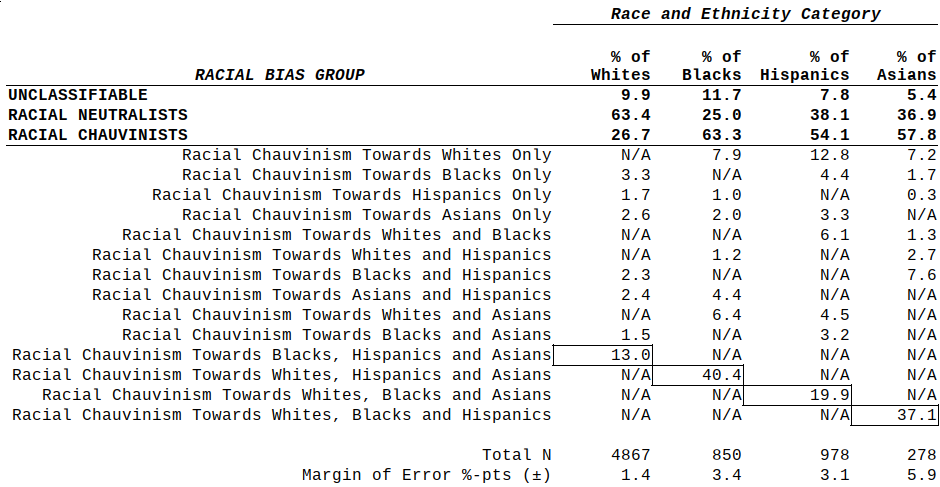

Figure 3 reveals the issue. The reality is that over half of Black, Hispanic, and Asian Americans hold racially-biased attitudes towards other races and ethnicities (63.3 percent, 54.1 percent, and 57.8 percent are racial chauvinists, respectively). In contrast, only 26.7 percent of whites are racial chauvinists.

Figure 3: Racial/ethnic bias within the 2020 U.S. electorate (by eligible voter’s race/ethnicity)

Even if we remove racial biases against whites from the equation, 55.4 percent of Black Americans possess racial biases against Hispanics and/or Asian Americans. Similarly, 41.3 of Hispanics and 50.6 percent of Asians hold racial biases against the other non-white racial and ethnic groups.

Judge not, that ye be not judged (Matthew 7:1)

There is a compelling argument within the racism-focused academic and activist communities that says Black Americans (and racial/ethnic minorities, in general) can’t be racist because racism requires a “power-over” relationship. Writes pastor and anti-racism activist Joseph Barndt:

“Racism goes beyond prejudice. Racism is the power to enforce one’s prejudices. More simply stated, racism is prejudice plus power.” [Dismantling Racism: The Continuing Challenge to White America (Minneapolis, 1991), 28.]

One reason I prefer the label ‘racial chauvinism’ to that of ‘racism’ in this essay is that the 2020 ANES survey items I use here are attitudinal measures, not behaviors. Thus, I use terms like chauvinism, prejudice, or bigotry as attitudinal indicators and reserve terms like racist or racism for the active implementation of prejudiced attitudes.

I acknowledge this may be pure semantics, but I have found this distinction useful in the past when analyzing racial bias, particularly in the context of survey-based data.

In the end, I am sympathetic to the argument that a white racial chauvinist generally occupies a different position in our society than a Black, Hispanic or Asian racial chauvinist;and, therefore, should not be treated as a substantive or operational equivalent.

Combined with institutional racism and demographic size disparities, white racial chauvinism is substantively more impactful in the aggregate.

Nevertheless, it is also wrong to ignore racial and ethnic prejudice existing within the non-white communities making up the Democrats’ electoral coalition.

Racial scholar Lawrence Blum, Professor of Liberal Arts and Education at the University of Massachusetts, concludes:

“Contemporary use of the vocabulary of racism no longer confines it to whites; Chinese, blacks, Japanese, Latinos, and other people of color are recognized to include in their ranks racially bigoted persons and, more broadly, to be subject to racial prejudices. These attitudes can be directed toward other groups of color, toward whites, or toward members of one’s own group. People of color are also capable of developing belief systems based on racial superiority, in which some groups of color are superior and whites or other groups of color are inferior…In my view, these attitudes and beliefs are all racist, and current usage generally so refers to them.”

Highlighting some sources of racial bias and prejudice while ignoring others is most likely not helpful in the long run and, frankly, paints a distorted picture of reality.

As such, media-driven tropes about the alleged tolerance within Republican ranks for ‘white supremacists’ are not just inaccurate, they are counterproductive if our goal is to achieve lasting progress in U.S. racial relations.

Given that 10 percent of Biden’s voter support in 2020 came from white chauvinists, it is time for Democrats to stop pretending the racial bias problem is isolated to Donald Trump supporters.

It is not.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: nuqum@protonmail.com

All data and SPSS computer programs used in writing this essay are available on GITHUB ==> HERE.

The science of creativity and the forever effervescent Syd Barrett

By Kent R. Kroeger (May 4, 2021)

“There is no great genius without a touch of madness.” — Aristotle (384 BC–322 BC)

“You are only given a little spot of madness, and if you lose that, you are nothing.” — Robin Williams (1951–2014)

“I know a mouse, and he hasn’t got a house. I don’t know why, I call him Gerald.” — Syd Barrett (1946–2006)

_________________

Just suppose clouds had strings attached to them which hang down to earth. What would happen?

How you answer this question may not only indicate your level of creativity, but also the likelihood you suffer from mental illness.

That was the discovery of neuroscientist Szabolcs Kéri of Semmelweis University in Hungary in a 2009 study that found a link between the presence of neuregulin 1, a gene commonly associated with psychosis and depression, and a person’s level of creativity.

“Molecular factors that are loosely associated with severe mental disorders but are present in many healthy people may have an advantage enabling us to think more creatively,” says Szabolcs.

In Szabolcs’ study, volunteers were asked a number of nonsensical questions like the ‘cloud’ question above. Szabolcs and his research team then assigned a creativity score to each study participant based on the originality and flexibility of their answers. Along with this assessment, the participants listed their lifetime creative achievements and provided blood samples.

“The results show a clear link between neuregulin 1 and creativity. Volunteers with the specific variant of this gene were more likely to have higher scores on the creativity assessment and also greater lifetime creative achievements than volunteers with a different form of the gene,” concluded Szabolcs and his research team.

There is also a 2010 study that tracked 700,000 Swedish 16-year-olds over ten years, which found that people who were high academic achievers at 16 years of age were four times as likely to be diagnosed with a bipolar disorder later in life.

In a 2012 science symposium that included a panel on the mental illness-creativity link, James Fallon, a neurobiologist at the University of California-Irvine, suggested that bipolar disorder and creativity share a common brain pattern:

When people are being creative, activity in the lower part of their frontal lobe decreases but rises in its higher regions — this is exactly what happens as well with bipolar patients when they come out of a deep depression.

Also on that panel, Elyn Saks, a mental health law professor at the University of Southern California, noted that people with psychosis have difficulty filtering out stimuli and therefore are more likely to hold contradictory or unrelated ideas simultaneously. While this result may make them appear ‘scatter brained,’ it may also unlock a degree of intellectual freedom necessary for producing something unique and profound.

As Aristotle’s quote indicates, observations of a link between genius and madness is as old as civilization itself.

Weep for the fragile poets who were overtaken by the monster

Rock-n-Roll history is strewn with creative talents also known for their intermittent madness. John Lennon. Kurt Cobain. Jim Morrison. Amy Winehouse. Janis Joplin. Michael Jackson. Phil Spector. Prince. Brian Wilson. Peter Green. Bjork.

But none is more fascinating than Syd Barrett, who gained rapid fame as the creative leader of Pink Floyd during 1967’s Summer of Love. Sadly, he would be out of the band by early January 1968, and died of pancreatic cancer in 2006 in near anonymity, save for a few die-hard Floyd fans who remembered his short but explosively innovative tenure with the band and as a solo artist.

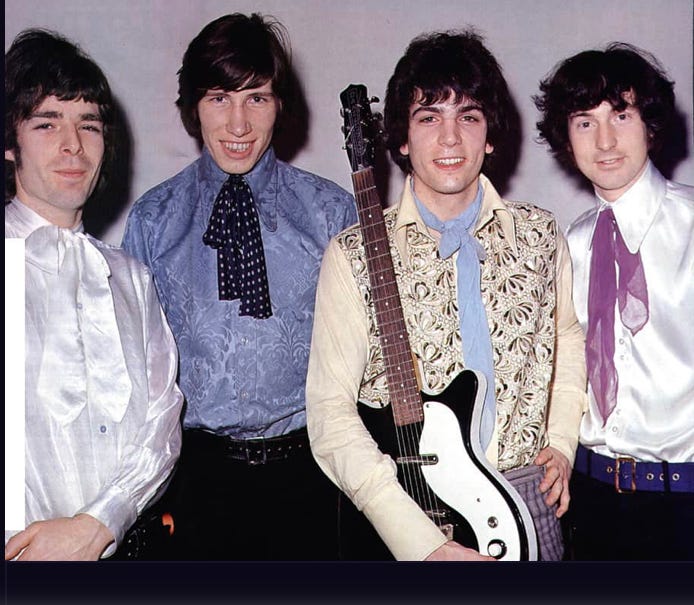

The original Floyd line-up in 1965 consisted of Roger Waters (bass guitar), Richard Wright (keyboards), Nick Mason (drums) and Barrett (lead guitar), with Barrett as the primary songwriter on the band’s first album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, and first two hit singles(Arnold Layne and See Emily Play).

Given the competitive, ruthless nature of the music industry, it is not that unusual to get kicked out of a band, even one you helped start. Think Brian Wilson (The Beach Boys), Brian Jones (The Rolling Stones), Steven Adler (Guns-n-Roses), Mick Jones (The Clash), Glen Matlock (The Sex Pistols), or Dave Mustaine (Metallica).

[Matlock’s involuntary exit from The Sex Pistols is particularly amusing given the band’s hardcore punk reputation: He talked too much about how he admired The Beatles, especially Paul McCartney.]

With all due respect to Brian Jones, who drowned only a month after getting booted from The Stones, no rock band departure is more tragic or iconic than Barrett’s.

The superficial facts alone surrounding Barrett’s dismissal from Floyd would be enough for legend. For starters, Barrett was replaced by his close friend, guitarist David Gilmour, who he met during their school days. Even more grimacing is how Barrett learned of his removal: The band stopped picking him up in the van they were taking to gigs. In a 1995 interview for Guitar World, Gilmour told of how the decision was finally made to kick Barrett out of the band: “One person in the car said, ‘Shall we pick Syd up?’ and another person said, ‘Let’s not bother.’”

That is as artless as it is cold.

Now there’s a look in your eyes, like black holes in the sky

But Barrett’s termination in early 1968 was not without cause. During live performances shortly after Floyd’s first UK hit, Arnold Layne, Barrett would occasionally stop playing mid-concert — in some instances, turning his back to the audience as the band continued to play.

Humble Pie drummer Jerry Shirley, who worked on Barrett’s first solo album (The Madcap Laughs), found Barrett “unnerving,” according to Barrett biographer Mike Watkinson,

“You could have a perfectly normal conversation with him for half-an-hour then he would suddenly switch off and his mind would go off somewhere else,” Shirley told Watkinson.

Shirley noticed another quirk in Barrett’s personality — his laugh: “Syd had a terrible habit of looking at you and laughing in a way that made you feel really stupid. He gave the impression he knew something you didn’t. He had this manic sort of giggle which made The Madcap Laughs such an appropriate name for his album — he really did laugh at you.”