By Kent R. Kroeger (May 4, 2021)

“There is no great genius without a touch of madness.” — Aristotle (384 BC–322 BC)

“You are only given a little spot of madness, and if you lose that, you are nothing.” — Robin Williams (1951–2014)

“I know a mouse, and he hasn’t got a house. I don’t know why, I call him Gerald.” — Syd Barrett (1946–2006)

_________________

Just suppose clouds had strings attached to them which hang down to earth. What would happen?

How you answer this question may not only indicate your level of creativity, but also the likelihood you suffer from mental illness.

That was the discovery of neuroscientist Szabolcs Kéri of Semmelweis University in Hungary in a 2009 study that found a link between the presence of neuregulin 1, a gene commonly associated with psychosis and depression, and a person’s level of creativity.

“Molecular factors that are loosely associated with severe mental disorders but are present in many healthy people may have an advantage enabling us to think more creatively,” says Szabolcs.

In Szabolcs’ study, volunteers were asked a number of nonsensical questions like the ‘cloud’ question above. Szabolcs and his research team then assigned a creativity score to each study participant based on the originality and flexibility of their answers. Along with this assessment, the participants listed their lifetime creative achievements and provided blood samples.

“The results show a clear link between neuregulin 1 and creativity. Volunteers with the specific variant of this gene were more likely to have higher scores on the creativity assessment and also greater lifetime creative achievements than volunteers with a different form of the gene,” concluded Szabolcs and his research team.

There is also a 2010 study that tracked 700,000 Swedish 16-year-olds over ten years, which found that people who were high academic achievers at 16 years of age were four times as likely to be diagnosed with a bipolar disorder later in life.

In a 2012 science symposium that included a panel on the mental illness-creativity link, James Fallon, a neurobiologist at the University of California-Irvine, suggested that bipolar disorder and creativity share a common brain pattern:

When people are being creative, activity in the lower part of their frontal lobe decreases but rises in its higher regions — this is exactly what happens as well with bipolar patients when they come out of a deep depression.

Also on that panel, Elyn Saks, a mental health law professor at the University of Southern California, noted that people with psychosis have difficulty filtering out stimuli and therefore are more likely to hold contradictory or unrelated ideas simultaneously. While this result may make them appear ‘scatter brained,’ it may also unlock a degree of intellectual freedom necessary for producing something unique and profound.

As Aristotle’s quote indicates, observations of a link between genius and madness is as old as civilization itself.

Weep for the fragile poets who were overtaken by the monster

Rock-n-Roll history is strewn with creative talents also known for their intermittent madness. John Lennon. Kurt Cobain. Jim Morrison. Amy Winehouse. Janis Joplin. Michael Jackson. Phil Spector. Prince. Brian Wilson. Peter Green. Bjork.

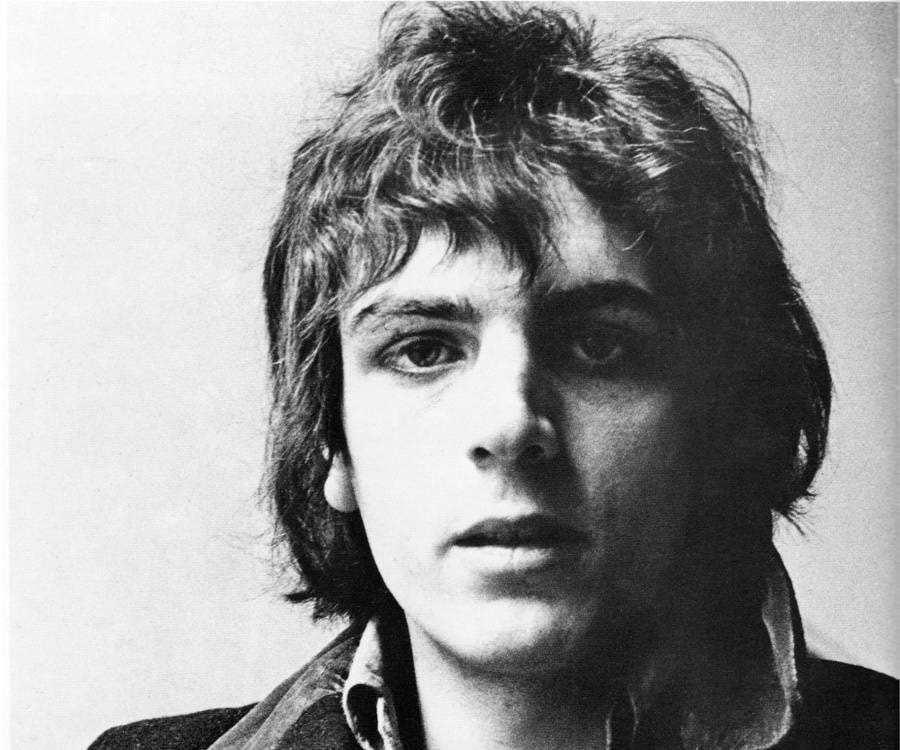

But none is more fascinating than Syd Barrett, who gained rapid fame as the creative leader of Pink Floyd during 1967’s Summer of Love. Sadly, he would be out of the band by early January 1968, and died of pancreatic cancer in 2006 in near anonymity, save for a few die-hard Floyd fans who remembered his short but explosively innovative tenure with the band and as a solo artist.

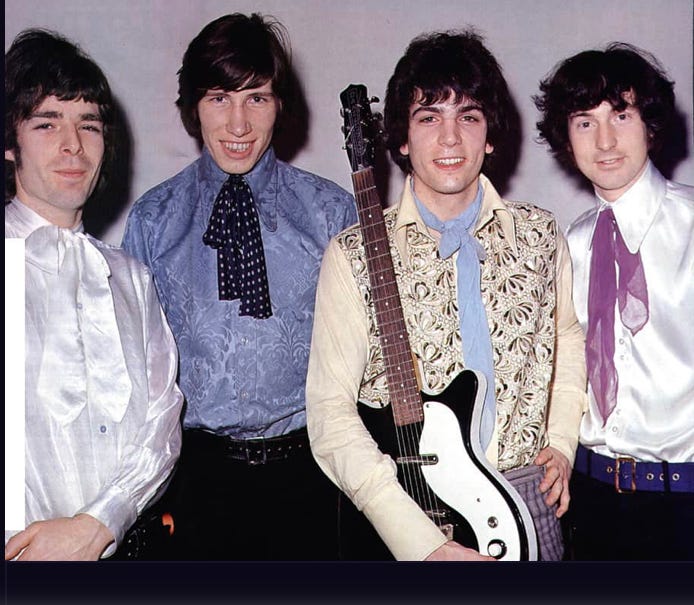

The original Floyd line-up in 1965 consisted of Roger Waters (bass guitar), Richard Wright (keyboards), Nick Mason (drums) and Barrett (lead guitar), with Barrett as the primary songwriter on the band’s first album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, and first two hit singles(Arnold Layne and See Emily Play).

Given the competitive, ruthless nature of the music industry, it is not that unusual to get kicked out of a band, even one you helped start. Think Brian Wilson (The Beach Boys), Brian Jones (The Rolling Stones), Steven Adler (Guns-n-Roses), Mick Jones (The Clash), Glen Matlock (The Sex Pistols), or Dave Mustaine (Metallica).

[Matlock’s involuntary exit from The Sex Pistols is particularly amusing given the band’s hardcore punk reputation: He talked too much about how he admired The Beatles, especially Paul McCartney.]

With all due respect to Brian Jones, who drowned only a month after getting booted from The Stones, no rock band departure is more tragic or iconic than Barrett’s.

The superficial facts alone surrounding Barrett’s dismissal from Floyd would be enough for legend. For starters, Barrett was replaced by his close friend, guitarist David Gilmour, who he met during their school days. Even more grimacing is how Barrett learned of his removal: The band stopped picking him up in the van they were taking to gigs. In a 1995 interview for Guitar World, Gilmour told of how the decision was finally made to kick Barrett out of the band: “One person in the car said, ‘Shall we pick Syd up?’ and another person said, ‘Let’s not bother.’”

That is as artless as it is cold.

Now there’s a look in your eyes, like black holes in the sky

But Barrett’s termination in early 1968 was not without cause. During live performances shortly after Floyd’s first UK hit, Arnold Layne, Barrett would occasionally stop playing mid-concert — in some instances, turning his back to the audience as the band continued to play.

Humble Pie drummer Jerry Shirley, who worked on Barrett’s first solo album (The Madcap Laughs), found Barrett “unnerving,” according to Barrett biographer Mike Watkinson,

“You could have a perfectly normal conversation with him for half-an-hour then he would suddenly switch off and his mind would go off somewhere else,” Shirley told Watkinson.

Shirley noticed another quirk in Barrett’s personality — his laugh: “Syd had a terrible habit of looking at you and laughing in a way that made you feel really stupid. He gave the impression he knew something you didn’t. He had this manic sort of giggle which made The Madcap Laughs such an appropriate name for his album — he really did laugh at you.”

In a 1978 interview with journalist Kris DiLorenzo, Shirley shared his observations about Barrett’s last days in Floyd:

“It was getting absolutely impossible for the band…Onstage he would either not play or he’d hit his guitar and just turn it out of tune, or do nothing. They were pulling their hair out, they decided to bring in another guitarist to complement, so Syd wouldn’t have to play guitar and maybe he’d just do the singing. Dave (Gilmour) came in and they were a five-piece for about four or five weeks…Then the ultimate decision came down that if they were going to survive as a band, Syd would have to go. Now I don’t know whether Syd felt it and left, or whether he was asked to. But he left. Dave went through some real heavy stuff for the first few months. Syd would turn up at London gigs and stand in front of the stage looking up at Dave; ‘That’s my band.’”

Job loss in rock-n-roll doesn’t get more awkward, and had Barrett just been an unpleasant dick, he would be little more than a footnote in rock history.

But Barrett was supremely creative and his dickish behavior seemed, at least to those who knew him best, to be correlated with his increased use of acid just as the band was becoming an international phenomenon.

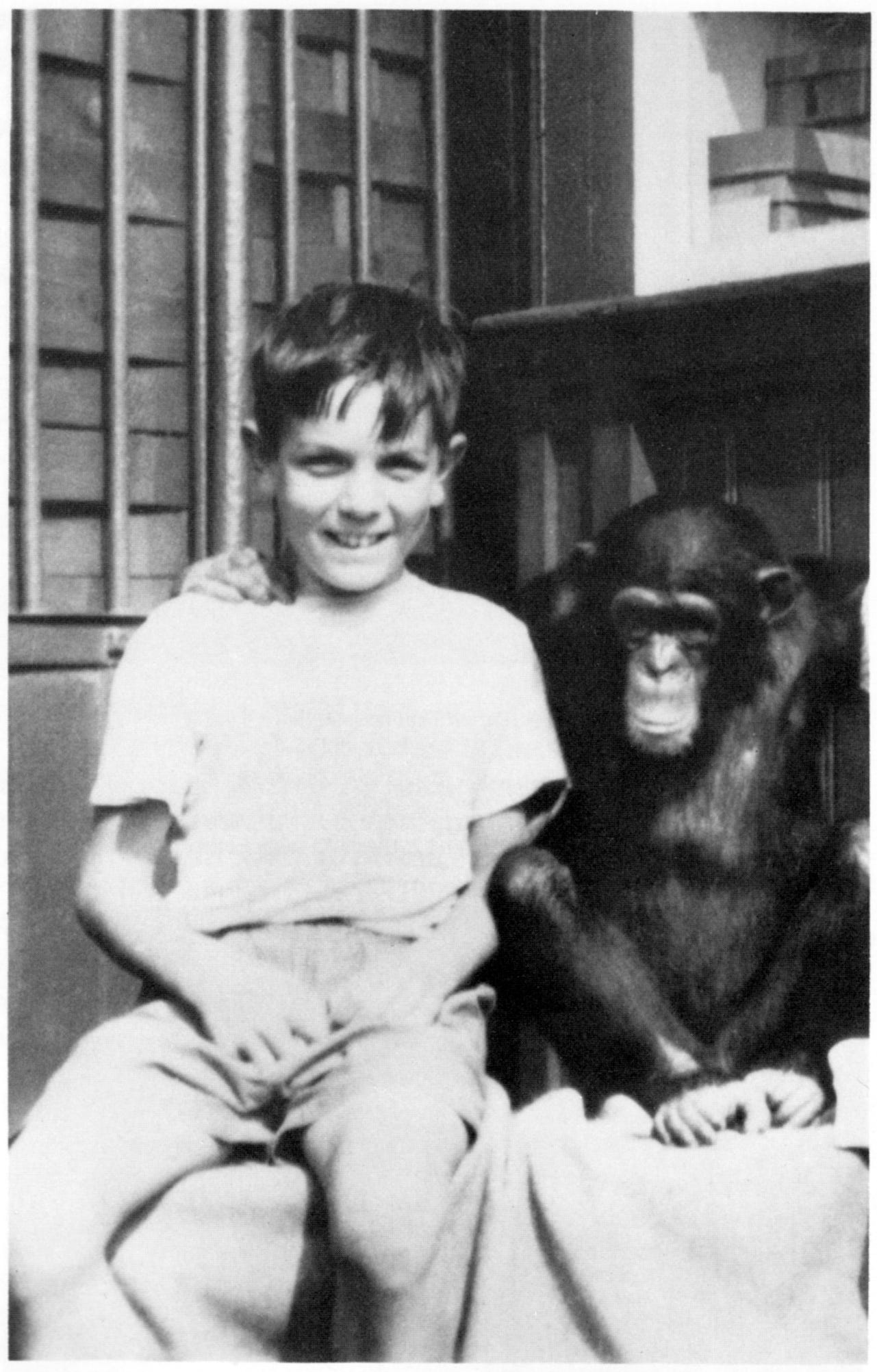

Among those who knew him before the Floyd fame, he was an engaging, likable young man. “He was always laughing, and always had a huge sparkle in his eyes as a child,” remembered Syd’s sister, Rosemary Breen, in an interview with the BBC’s John Harris shortly after Syd’s death in 2006. “He was exceptionally gifted and always had loads and loads of friends.”

One of his first girlfriends, Jenny Spires, met Barrett at 15 years old when he was 18, and said about him: “He was a lovely person, and my parents liked him too. My dad knew of his dad, and he and my mum just hit it off, so they felt very safe with me going around with him.”

Barrett’s bandmate and close friend, Richard Wright, briefly lived with him in 1967–8 as part of the band’s attempt to nudge him back into normalcy, and observed his descent firsthand. In a BBC interview, Wright recalled:

“There were two Syds. There was the pre-acid and the post-acid, and the pre-acid Syd was just this wonderful, open and flamboyant guy. And, clearly, we were all hoping he’d get better and all desperately trying as hard as possible to keep him in the band — we all loved him.”

“He was a great talent, but he was also bloody difficult,” was the inelaborate description of Barrett offered by Floyd’s drummer, Nick Mason.

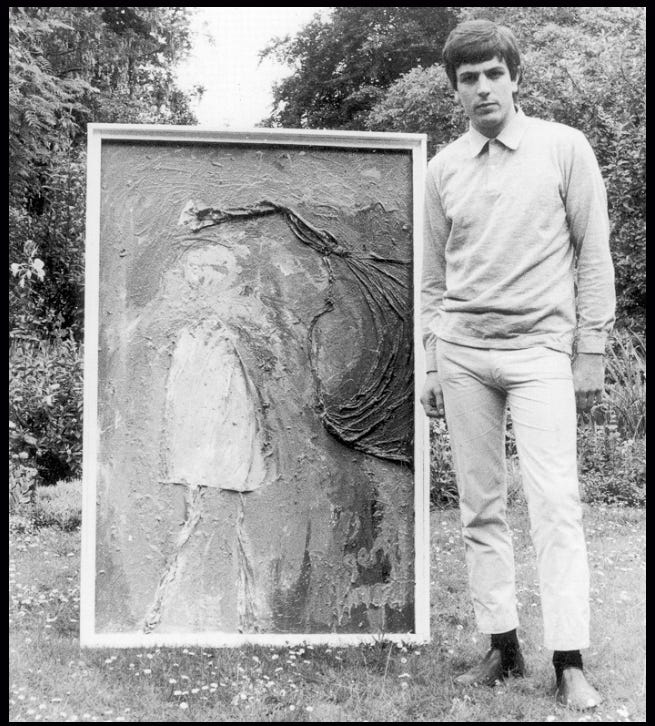

The once charismatic and outgoing art student from Cambridge vanished, and in the span of a year, Barrett would withdraw into a mental lockbox that no one knew how to unlock. In 1968, at the cusp of Beatlesque-like stardom, something had caused seemingly irreversible changes to Barrett’s captivating, though quirky, personality. But what?

His excessive use of LSD has become the accepted myth.

“Roger (Waters) had a theory he was schizophrenic. I don’t think he was. But I’m still convinced he took a huge overdose of acid and destroyed his brain cells,” said Wright, who died in 2008 of lung cancer.

Yet, there remains significant doubts within the medical community as to whether LSD actually kills brain cells and creates life-disabling psychoses.

“So far, there’s not much evidence to suggest that LSD has long-term effects on the brain,” according to Zara Risoldi Cochrane, Pharm.D., M.S., FASCP and Adrienne Santos-Longhurst. “A large survey published in 2015 found no link between psychedelics and psychosis. This further suggests there are other elements at play in this connection, including existing mental health conditions and risk factors.”

Though the cause of Barrett’s mental decline is disputed, the result is not.

After his dismissal from Floyd, Barrett would in 1970 record two solo albums (The Madcap Laughs and Barrett), but never achieved anything close to the commercial success Floyd would enjoy in the 1970s.

Soon after Barrett’s last live performance on June 6, 1970 at Olympia Exhibition Hall in London, with Gilmour joining him onstage on bass guitar, he left the music business and eventually moved in with his mother and sister in Cambridge.

Apart from an unannounced visit to Abbey Road studios in 1975 — where his former band, ironically, was mixing the song Shine on You Crazy Diamond whichthey had written about their former bandmate — Barrett disappeared from public life.

And so began the growing myth of Syd Barrett.

An effervescing elephant with tiny eyes and great big trunk

As is usually the case, myth typically exaggerates reality, especially as time passes. As an example, try as I do to appreciate the comedic brilliance of late comedian Lenny Bruce, I just don’t find him funny — not even a little. [Here is one of his more accessible appearances: The Steve Allen Show — April, 5, 1959.]

And I could see a hundred more Jackson Pollack paintings and still think my dog with paint brushes tied to his paws could create something just as thoughtful.

Similarly, not every music critic appreciates Syd Barrett’s songs or musicianship. His lead guitar playing could range from powerful to hellishly inventive to sloppy to ‘What the hell is he doing?!’ — sometimes all within the same song. As for his songs, some would include unusual chord changes or chords that don’t even exist (such as at the 0:43 mark in Dark Globe), while others could change time signatures multiple times, making them difficult for other bands to cover (e.g., Bike from The Piper at the Gates of Dawn).

Rock critic Bill Wyman (not to be confused with The Rolling Stone’s bassist) wrote of Barrett’s songs:

“The argument against Syd Barrett is that, to use a turn of phrase he might have heard in his Cambridge days, even his best songs are curate’s eggs — parts, that is to say, are excellent. But that’s as far as it goes with all but a few of the songs he’s left behind. I respect the Barrett amen corner; but the plain truth is that it’s hard to come up with one Barrett song that’s as good as, say, (The Kink’s) Waterloo Sunset or even (Status Quo’s) Pictures of Matchstick Men.”

Matched against Waterloo Sunset, a pop music masterpiece, few popular music songs survive the comparison. And the brevity of Barrett’s productive songwriting years (1966–1970) must also be considered before making connections to the Ray Davies, Leiber-Stoller, Lennon-McCartney, or Jagger-Richards song catalogs.

Furthermore, Barrett’s experimentalism observed no restrictions when he and his bandmates took rock music down a path that sometimes, to my Beatle-nurtured ears, created sounds similar to that of a gang of feral cats attacking a bad teenage garage band. The last two-and-a-half minutes ofPow R. Toc H., co-written by Barrett with Waters, Wright and Mason, is representative of that modal apocalypse. It’s basically nails-on-chalkboard screeching noise.

However, Barrett’s best songs, while often unpolished and in need of a George Martin-like influence in the studio and editing phases, still stand the test of time and cover a stylistic and lyrical range as broad as the best popular artists of his time, including Ray Davies and Lennon-McCartney.

On Barrett’s death in 2006, David Bowie said “Syd was a startlingly original songwriter.”

Nonetheless, Wyman insists Barrett’s music revealed his “promise,” not evidence of his genius. From the perspective of musicality, I can accept his conclusion, but I would add that ‘genius’ and ‘creativity’ are not synonyms. Barrett was a creative savant who may well have lacked the comprehensive knowledge and discipline to earn the additional label of ‘genius.’ [I like to point out during discussions like this that Albert Einstein, who fundamentally reshaped the field of physics and our understanding of the universe, also lacked the discipline necessary to finish his PhD.]

If I had to make a comparison, Barrett’s songs are reminiscent of John Lennon’s ability to blend free-associative lyrics with strident rock guitar melodies, à la I Am The Walrus or And Your Bird Can Sing. And Barrett, like Lennon, had a preternatural knack for writing memorable and hummable pop ditties.

The Barrett song that best exemplifies that for me is one he wrote as a teenager — Effervescing Elephant, recorded for the 1970 album “Barrett.” On a first listen, it sounds like little more than a catchy children’s song, like a tune out of Walt Disney’s The Jungle Book. But with subsequent listens a listener starts to recognize its unpretentiously clever and dark lyrics are quite remarkable — a lyrical revelation that stands with Lennon’s best:

An Effervescing Elephant

With tiny eyes and great big trunk

Once whispered to the tiny ear

The ear of one inferior

That by next June he’d die, oh yeah!

Because the tiger would roam

The little one said, “Oh my goodness I must stay at home”

And every time I hear a growl

I’ll know the tiger’s on the prowl

And I’ll be really safe, you know

The elephant he told me so

Everyone was nervy, oh yeah!

And the message was spread

To zebra, mongoose, and the dirty hippopotamus

Who wallowed in the mud and chewed

His spicy hippo-plankton food

And tended to ignore the word

Preferring to survey a herd

Of stupid water bison, oh yeah

And all the jungle took fright

And ran around for all the day and the night

But all in vain, because, you see

The tiger came and said “Who me?

You know I wouldn’t hurt not one of you

I’d much prefer something to chew

And your all to scant.” Oh yeah!

He ate the elephant

Why I am teaching Barrett songs to my son

Whether or not Syd Barrett ‘fried’ is brain on LSD is immaterial at this point. And I don’t believe ‘madness’ is a necessary companion to creativity. I’ve met some very creative people who are also very sane.

Indisputable, however, is that for a brief moment in rock history some wonderful music and words flowed from Barrett’s mind that were so creative — so celestially inspired — that they sound as insurgent today as they must have seemed fifty years ago.

Today, as I sat with my son in our home’s music room, guitars in hand and Fender amps in the ready, we started to master fingering and strumming a A7 — C — Dm chord progression in the hope that we can perform, with passable merit, my favorite Barrett song, Dominoes.

At the time of his death in 2006, I only knew Barrett as ‘the guy who left Pink Floyd before they became really famous.’ Since then, it has taken my own personal struggles, along with helping my teenage son prepare for life’s inevitable challenges, to fully appreciate Barrett’s creative purpose. I feel at peace when I play his songs.

Roger “Syd” Barrett, we are grateful for what you’ve left us.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to nuqum@protonmail.com

The 15 Essential Syd Barrett Songs

[Click on song name to hear]

15. Maisie (from Barrett, 1970) — Syd loved the Blues (along with Jazz); accordingly, this song is musical swamp water.

14. Effervescing Elephant (from Barrett, 1970) — Closing Syd’s second solo album, this song probably deserves to be higher on the list; it is clever, snappy and would be a cherished chestnut in any other songwriter’s catalog.

13. Jugband Blues (from A Saucerful of Secrets, 1968) — Syd’s goodbye letter to his bandmates; in the song’s promotional video, at the song’s end, Syd turns to Roger Waters after he sings, “And what exactly is a dream? And what exactly is a joke?” — it is heartbreaking.

12. Lucifer Sam (from The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, 1967) — A combination of James Bond and Lewis Carroll; it is apparently a song about Syd’s cat.

11. Octopus (from The Madcap Laughs, 1970) — I love the Bo Diddley tribute in the middle.

10. Love You (from The Madcap Laughs, 1970) — I heard this song at a wedding once; a fun, bouncy tune that changes time signatures more times than Lady Gaga changes costumes in concert.

9. Terrapin (from The Madcap Laughs, 1970) — An “easy” song to learn but, strangely, hard to play.

8. Bob Dylan Blues (released in 2001) — Recorded in 1969 (or thereabouts), this song both mocks and honors Bob Dylan.

7. See Emily Play (Pink Floyd’s second single; released in Nov. 1967) — This song proves Pink Floyd was a different band with Syd as the front man.

6. Arnold Layne (Pink Floyd’s first single; released in March 1967) — The song’s video is lifted straight out of A Hard Day’s Night; andthe song’s A to F# chord changes still give me chills.

5. Here I Go (from The Madcap Laughs, 1970) — Syd’s best self-referential song that also highlights his great voice when singing in a low register.

4. Baby Lemonade (from Barrett, 1970) — The opening song on his second solo album; the oft-repeated chorus may only be five seconds long, but it is guaranteed to raise the hair on your neck.

3. Bike (from The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, 1967) — Probably Syd’s most recognized song; for good reason, it’s deceptively childlike, quirky lyrics ride on top of a Beatlesque melody that is impossible to get out of your head once heard.

2. Interstellar Overdrive (from The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, 1967) — a psychedelic rock masterpiece with an opening lead guitar that stands up to anything heavy metal would produce in subsequent years; if I were starting a rock band, we’d open every concert with the first 50 seconds of this song.

1. Dominoes (from Barrett, 1970) — One of those simple Syd songs that shows his “promise” as some prefer to call it; in truth, the song is haunting and brilliant — I wouldn’t change a note. [David Gilmour’s live version is worth a listen too.]

Honorable mentions:

Vegetable Man (recorded by Pink Floyd in 1967, but unreleased until 2016) — This is the song Syd came up with for Pink Floyd’s third single and now marks what was probably the end of Syd’s relevance to the band; it was uncategorically rejected by the record company and would go unreleased for five decades; yet, if you heard it today, you would be forgiven if you thought it was a punk rock classic. Syd was ahead of his time.

Astronomy Domine (from The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, 1967) — Another group effort by Pink Floyd, but Syd’s guitar dominates; and while I prefer Interstellar Overdrive, this song remains firmly in the pantheon of psychedelic rock’s greatest songs.

Milky Way (from Opel, 1988, a collection of unreleased Syd solo compositions recorded around 1970) — The world is a pretty lonely and scary place when your reality is not the same as others’ around you; this song puts that sentiment to music.

Clowns and Jugglers (from Opel, 1988) — This may just be a remixing of Octopus, from The Madcap Laughs, but more than a few Syd fans prefer this version; Lennon was doing musical cacophonies like this in the late 1960s (take a listen to What’s the New Mary Jane), but Syd’s scattered madness was more than its musical match.