By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; January 25, 2021)

Some background music while you read ==> Undiscovered Moon (by Miguel Johnson)

Shane Smith, an intern in the University of California at Berkeley’s Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) program, was the first to see the anomaly buried in petabytes of Parkes Radio Observatory data.

It was sometime in October of last year, the start of Australia’s spring. when Smith found a strange, unmodulated narrowband emission at 982.002 megahertz seemingly from Proxima Centauri, our Sun’s closest star neighbor.

While there have been other intriguing radio emissions — 1977’s “Wow” signal being the most famous — none have offered conclusive evidence of alien civilizations. Similarly, the odds are in favor of the Parkes signal being explained by something less dramatic than extraterrestrial life; but, as of now, that has not happened.

“It has some particular properties that caused it to pass many of our checks, and we cannot yet explain it,” Dr. Andrew Siemion. director of the University of California, Berkeley’s SETI Research Center, told Scientific American recently. “We don’t know of any natural way to compress electromagnetic energy into a single bin in frequency,” Siemion says. “For the moment, the only source that we know of is technological.”

Proof of an extraterrestrial intelligence? No, but initial evidence offering the intriguing possibility? Why not. And if another radio telescope were to also detect this tone at 982.002 megahertz coming from Proxima Centauri, a cattle stampede of conjecture would likely erupt.

As yet, however, the scientists behind the Parkes Radio Telescope observations have not published the details of their potentially momentous discovery, as they still contend, publicly, that the most likely explanation for their data is human-sourced.

“The chances against this being an artificial signal from Proxima Centauri seem staggering,” says Dr. Lewis Dartnell, an astrobiologist and professor of science communication at the University of Westminster (UK).

Is there room for “wild speculation” in science?

We live in a time when being called a “conspiracy theorist” is among the worst smears possible, not matter how dishonest or unproductive the charge. How dare you not agree with consensus opinion!

However science, presumably, operates above the daily machinations of us peons. How could any scientist make a revolutionary discovery if not by tearing down consensus opinion? Do you think when Albert Einstein published his relativity papers he was universally embraced by the scientific community? Of course not.

“Sometimes scientists have too much invested in the status quo to accept a new way of looking at things,” says writer Matthew Wills, who studied how the scientific establishment in Einstein’s time reacted to his relativity theories.

But just because scientists cannot yet explain the Parkes signal doesn’t mean the most logical conclusion should be “aliens.” There are many less dramatic explanations that also remain under consideration.

At the same time, we need to prepare ourselves for the possibility the Parkes signal cannot be explained as a human-created or natural phenomenon.

“Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” — Astrophysicist Carl Sagan’s rewording of Laplace’s principle, which says that “the weight of evidence for an extraordinary claim must be proportioned to its strangeness”

“When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” — Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, stated by Sherlock Holmes.

The late Carl Sagan was a scientist but became famous as the host of the PBS show “Cosmos” in the 1980s. Sherlock Holmes, of course, is a fictional character conceived by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. It should surprise few then that Sagan’s quote about ‘extraordinary claims’ aligns comfortably with mainstream scientific thinking, while the Holmes quote is referred to among logicians and scientific philosophers as the process of elimination fallacy — when an explanation is asserted as true on the belief that all alternate explanations have been eliminated when, in truth, not all alternate explanations have been considered.

If you are a scientist wanting tenure at a major research university, you hold the Sagan (Laplace) quote in high regard, not the Holmesian one.

The two quotes encourage very different scientific outcomes: Sagan’s biases science towards status quo thinking (not always a bad thing), while Holmes’ aggressively pushes outward the envelope of the possible (not always a good thing).

Both serve an important role in scientific inquiry.

Oumuamua’s 2017 pass-by

Harvard astronomer Dr. Abraham (“Avi”) Loeb, the Frank B. Baird Jr. Professor of Science at Harvard University, consciously uses both quotes when discussing his upcoming book, “Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth,” as he recently did on the YouTube podcast “Event Horizon,” hosted by John Michael Godier.

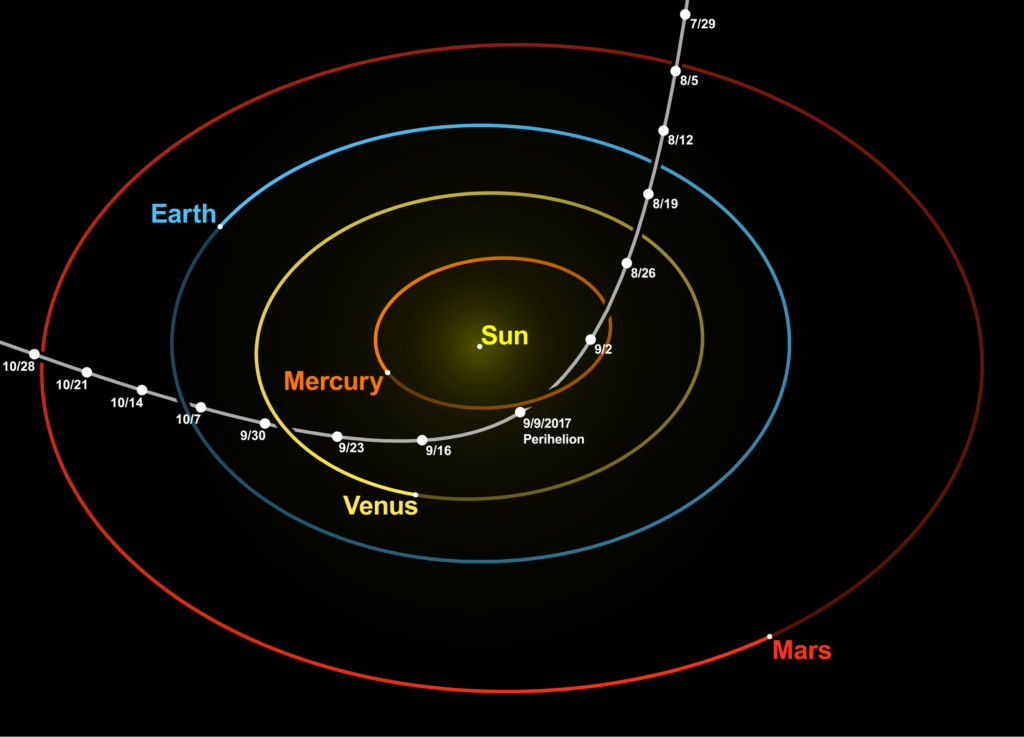

His book details why he believes that the first observed interstellar object in our solar system, first sighted in 2017 and nicknamed Oumuamua (the Hawaiian term for ‘scout’), might have been created by an alien civilization and could be either some of their space junk or a space probe designed to observe our solar system, particularly the third planet from the Sun. For his assertion about Oumuamua, Dr. Loeb has faced significant resistance (even ridicule) from many in the scientific community.

Canadian astronomer Dr. Robert Weryk calls Dr. Loeb’s alien conclusion “wild speculation.” But even if Dr. Wertk is correct, what is wrong some analytic provocation now and then? Can heretical scientific discoveries advance without it?

Dr. Loeb, in turn, chides his critics right back for their lack of intellectual flexibility: “Suppose you took a cell phone and showed it to a cave person. The cave person would say it was a nice rock. The cave person is used to rocks.”

Dr. Loeb’s controversial conclusion about Oumuamuaformed soonafter it became apparent that Oumuamua’s original home was from outside our solar system and that its physical characteristics are unlike anything we’ve observed prior. Two characteristics specifically encourage speculation about Oumuamua’s possible artificial origins: First, it is highly elongated, perhaps a 10-to-1 aspect ratio. If confirmed, it is unlike any asteroid or comet ever observed, according to NASA. And, second, it was observed accelerating as it started to exit our solar system without showing large amounts of dust and gas being ejected as it passed near our Sun, as is the case with comets.

In stark contrast to comets and other natural objects in our solar system, Oumuamua is very dry and unusually shiny (for an asteroid). Furthermore, according to Dr. Loeb, the current data on its shape cannot rule out the possibility that it is flat — like a sail — though the consensus view remains that Oumuamua is long, rounded (not flat) and possibly the remnants of a planet that was shredded by a distant star.

I should point out that other scientists have responded in detail to Dr. Loeb’s reasons for suggesting Oumuamua might be alien technology and an excellent summary of those responses can be found here.

Place your bets on whether the Parkes signal and/or Oumuamua are signs of alien intelligence

What are the chances Oumuamua or the Parkes signal are evidence of extraterrestrial intelligent life?

If one asks mainstream scientists, the answers would cluster near ‘zero.’ Even the scientists involved in discovering the Parkes signal will say that. “The most likely thing is that it’s some human cause,” says Pete Worden, executive director of the Breakthrough Initiatives, the project responsible for detecting the Parkes signal. “And when I say most likely, it’s like 99.9 [percent].”

In 2011, radiation from a microwave oven in the lunchroom at Parkes Observatory was, at first, mistakenly confused with an interstellar radio signal. These things happen when you put radiation sources near radio telescopes looking for radiation.

Possibly the most discouraging news for those of us who believe advanced extraterrestrial intelligence commonly exists in our galaxy is a recent statistical analysis published in May 2020 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by Dr. David Kipping, an assistant professor in Columbia University’s Department of Astronomy.

In his paper, Dr. Kipping employs an objective Bayesian analysis to estimate the odds ratios for the early emergence of life on an alien planet and for the subsequent development of intelligent life. Since he only had a sample size of 1 — Earth — he used Earth’s timeline for the emergence of early life (which occurred about 500 million years after Earth’s formation) and intelligent life (which took another 4 billion years) to run a Monte Carlo simulation. In other words, he estimated how often elementary life forms and then intelligent life would emerge if we repeated Earth’s history many times over.

Dr. Kipping’s answer? “Our results find betting odds of >3:1 that abiogenesis (the first emergence of life) is indeed a rapid process versus a slow and rare scenario, but 3:2 odds that intelligence may be rare,” concludes Dr. Kipping.

Put differently, there is a 75 percent change our galaxy is full of low-level life forms that formed early in a planet’s history, but a 60 percent chance that human-like intelligence is quite rare.

Dr. Kipping is not suggesting humans are alone in the galaxy, but his results suggest we are rare enough that to have a similarly intelligent life form living in our nearest neighboring solar system, Proxima Centauri, is unlikely.

What a killjoy.

My POOMA-estimate of Extraterrestrial Intelligent Life

I want to believe aliens living in the Proxima Centauri system are broadcasting a beacon towards Earth saying, in effect, “We are over here!” I also want to believe Oumuamua is an alien probe (akin to our Voyager probes now leaving the confines of our solar system).

If either is true (and we may never know), it would be the biggest event in human history…at least until the alien invasion that will follow happens.

Both events leave me with questions: If Oumuamua is a reconnaissance probe, shouldn’t we have detected electromagnetic signatures suggesting such a mission? [It could be a dead probe.] And in the case of the Parkes signal, if a civilization is going to go to the trouble of creating a beacon signal (which requires a lot of energy directed at a specific target in order to be detectable at great distances), why not throw some information into the signal? Something like, “We are Vulcans. What is your name?” or “When is a good time for us to visit?” And why do these signals never reappear? [At this writing, there have been no additional narrowband signals detected from Proxima Centauri subsequent to the ones found last year.]

Given the partisan insanity that grips our nation and the fear-mongering meat heads that overpopulate our two political parties, we would be well-served by a genuine planetary menace. We would all gain some perspective. And I’ll say it now, in case they are listening: I, for one, welcome our new intergalactic overlords (Yes, I stole that line from “The Simpsons”).

In the face of an intergalactic invasion force, we may look back and realize that a lot of the circumstantial evidence of extraterrestrial life we had previously dismissed as foil-hat-level speculation was, in reality, part of a bread crumb trail to a clearer understanding of our place in the galactic expanse.

So, are Oumuamua and the possible radio signal from the Proxima Centauri system evidence of advanced extraterrestrial life? In isolation, probably not. But I wonder what evidence we have overlooked because our best scientific minds are too career conscious to risk their professional reputations.

I don’t have a professional reputation to protect, so here is my guess as to whether Oumuamua and/or the possible Proxima Centauri radio signal are actual evidence of advanced extraterrestrial life: A solid 5 percent probability.

The chance that we’ve overlooked other confirmatory evidence already captured by our scientists? A much higher chance…say, a plucky 20 percent probability.

Turning the question around, given our time on Earth, our technology, and the amount of time we’ve been broadcasting towards the stars, what are the chances an alien civilization living nearby would detect our civilization? Probably a rather good chance, but not in the way they did in the 1997 movie Contact. There is no way the 1936 Berlin Olympics broadcast would be detectable and recoverable even a few light-years away from Earth. Instead, aliens are more likely to see evidence of life in the composition of our atmosphere.

And what is my estimated probability that advanced extraterrestrial life (of the space-traveling kind) lives in our tiny corner of the Milky Way — say, within 50 light years of our sun? Given there are at least 133 Sun-like stars within this distance (many with planets in the organic life-friendly Goldilocks- zone) and probably 1,000 more planetary systems orbiting red dwarf stars, I give it an optimistic 90 percent chance that intelligent life lives nearby.

We are not likely to be alone. In fact, we probably don’t have the biggest house or the smartest kids in our own cul-de-sac. We are probably average.

I am even more convinced that we live in a galaxy densely-populated with life on every point of the advancement scale, a galactic menagerie of life that has more in common with Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek than Dr. Kippling’s 3:2 odds estimate against such intelligent life abundance.

So, it won’t surprise me if someday we learn that aliens in the Proxima Centauri system were trying to contact us or that Oumuamua was a reconnaissance mission of our solar system by aliens looking for a hospitable place to explore (and perhaps spend holidays if the climate permits). I’m not saying that is what happened, I’m just saying I would not be surprised.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: nuqum@protonmail.com