By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, September 21, 2022)

[Disclaimer: The opinions (and errors) expressed in this essay are mine alone and do not represent the opinions of any of the media companies or creative properties mentioned herein.]

Amazon’s The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power TV series is going to be the most expensive TV show in history, with Amazon spending $465 million for its first season. When its five seasons are over, its total budget will be measured in the billions of dollars.

By comparison, HBO’s The House of the Dragon cost $200 million for its first season, and Netflix’s extraordinarily popular Stranger Things cost $270 million for its fourth season.

The problem for Amazon is that The House of the Dragon and Stranger Things are arguably audience-grabbing successes and, so far, it is not clear if The Rings of Power has found a mass audience.

When Season 4 of Stranger Things debuted in late June 2022, an estimated 301.3 million hours were watched, according to Netflix. As for The House of the Dragon, HBO reported 25 million people watched the August 2022 premiere in just over a week. Not to be outdone, Amazon reported the first episode of The Rings of Power, which debuted September 1, 2022, was watched by more than 25 million globally.

Would Netflix, HBO or Amazon shade the truth about their audience numbers? Of course they would. It would be criminally incompetent not to do so.

But how can we objectively decide if Stranger Things or The House of Dragons or The Rings of Power are, genuinely, popular with audiences? And how do they compare with each other?

Are streaming audience measurements believable?

At a time when consistent, credible audience measurement for streaming programs is still contentious, it is hard to find universally-accepted measures of audience interest in popular TV shows. They all have flaws.

Unfortunately, too many of the audience measurement stories published in the mainstream media use the content providers (e.g., Netflix, HBO, Disney+, etc.) as the primary sources for their own audience data. That isn’t journalism — that is called being a shill. More importantly, that is a recipe for unacceptable levels of corporate-friendly news bias.

Sadly, there are few audience data alternatives, particularly for independent researchers like myself who cannot justify the subscription fees for audience measurement services like Nielsen Media Research, Symphony Technology Group and GfK.

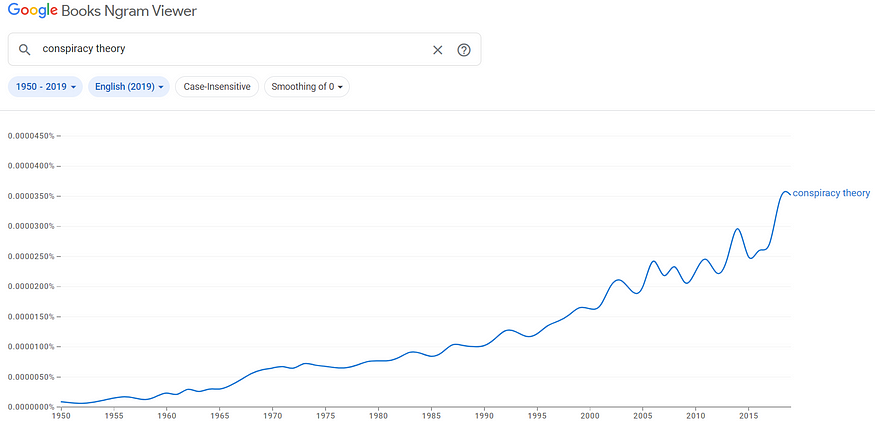

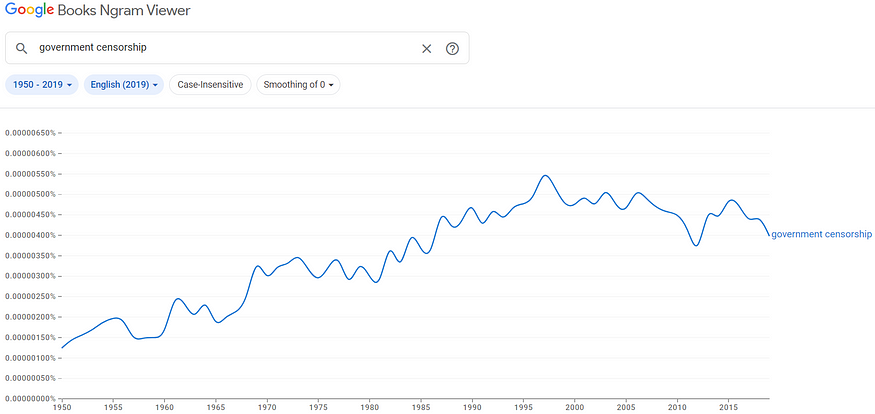

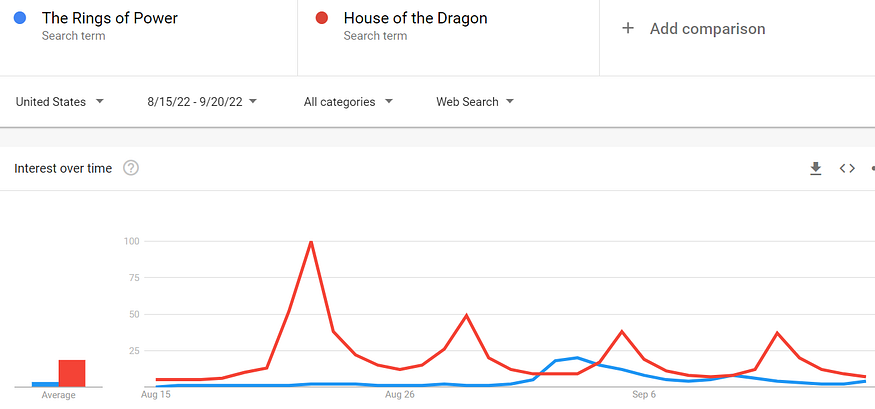

So I turn to Google Trends (GT). But is it an objective measure of audience interest? Probably not in the academic sense. The limited amount of quantitative analyses on GT’s objectivity and reliability suggests there are systematic biases in its data, and its ability to predict to predict consumer behavior (such as car sales) is dubious.

However, my own research has shown a strong correlation between GT search data and independent measures of TV streaming audiences.

It is entirely possible that GT statistics are biased and, nonetheless, a useful way to compare the relative popularity of streamed TV shows.

Of course, large corporations use their enormous financial resources to influence Google searches and other indicators of audience interest. They have every financial incentive to do so.

But it can also be assumed that the concerted actions of large corporations to manipulate social media and search engine numbers is a constant within the system. HBO (Warner Bros.) and Amazon are not resource-challenged, which is why data manipulation is unavoidable in today’s online media environment.

Yet, based on the evidence I’ve collected, GT remains a valuable, publicly-available data source for assessing the public’s interest in different media properties.

And if GT is a reliable data source, the news for The Rings of Power looks very grim, at least as of September 20, 2022.

‘The Rings of Power’ has not found an audience

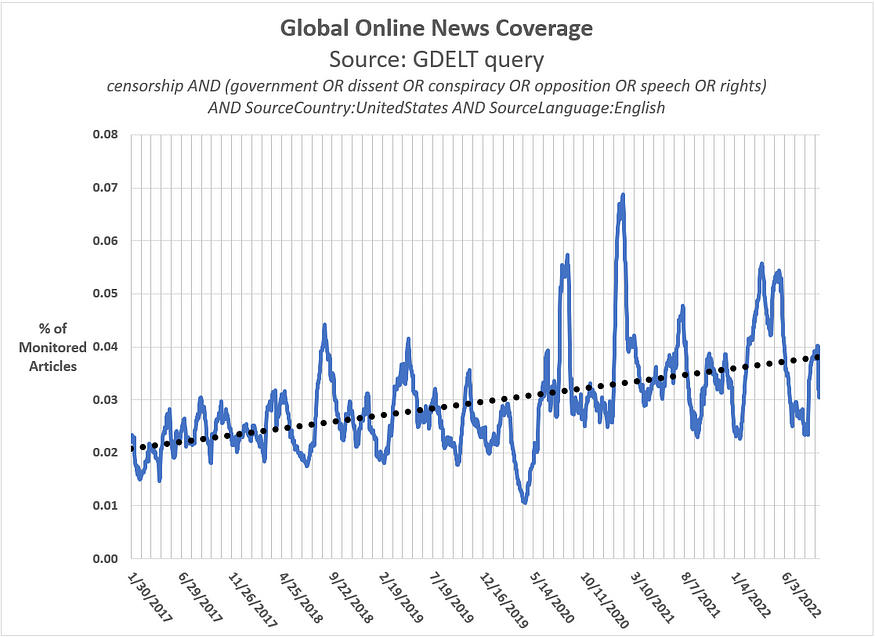

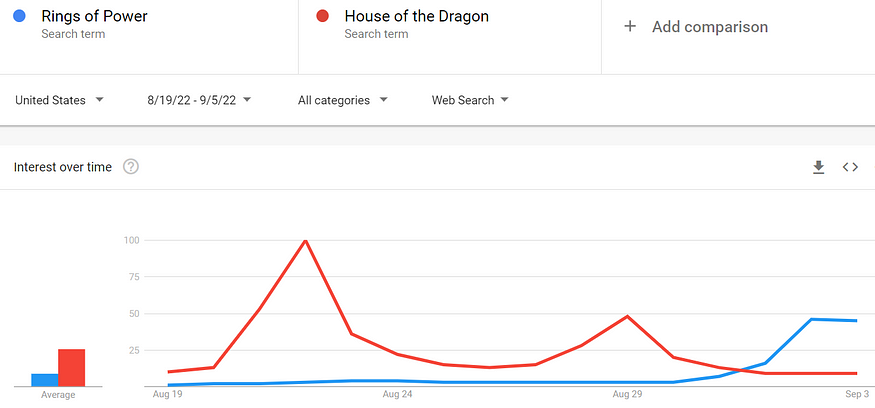

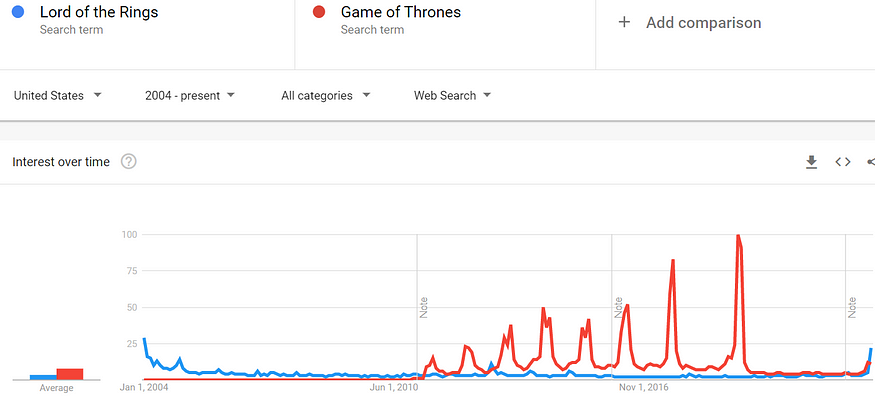

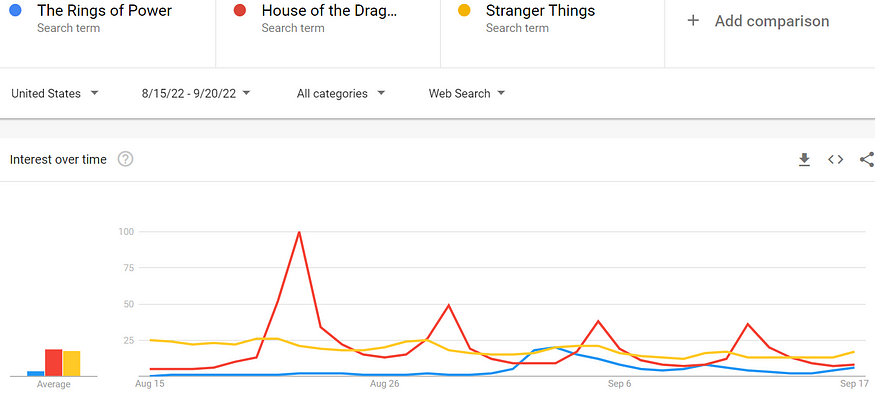

Looking at Google search interest in the U.S. for The Rings of Power (TRP) and The House of the Dragon (THD) since their streaming debuts, THD is almost five times more interesting to Americans (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Google search trends for The Rings of Power and The House of the Dragon (August 15 — September 20, 2022)

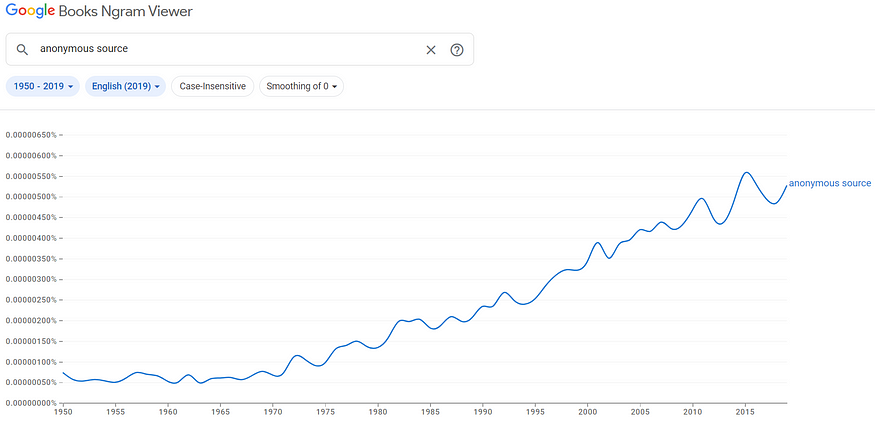

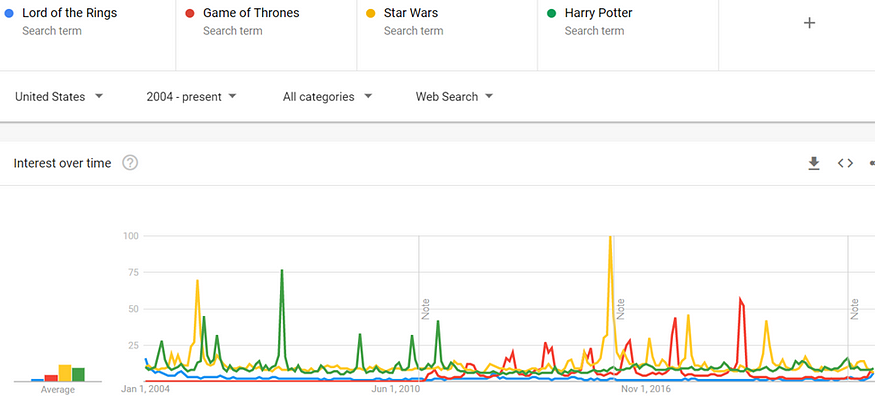

Amazon didn’t spend $465 million on TRP to generate levels of interest significantly below their arch rival, HBO. But compare Google search trends for TRP and THD to an undeniable TV series powerhouse, Stranger Things, and one must wonder if HBO and Amazon are themselves perennial runner-ups to Netflix (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Google search trends for Stranger Things, The Rings of Power and The House of the Dragon (August 15 — September 20, 2022)

Stranger Things is two months removed from its 2022 season premiere and it still generates as much Google search interest (in the U.S.) as THD.

That is what a social phenomenon looks like.

TRP is not that.

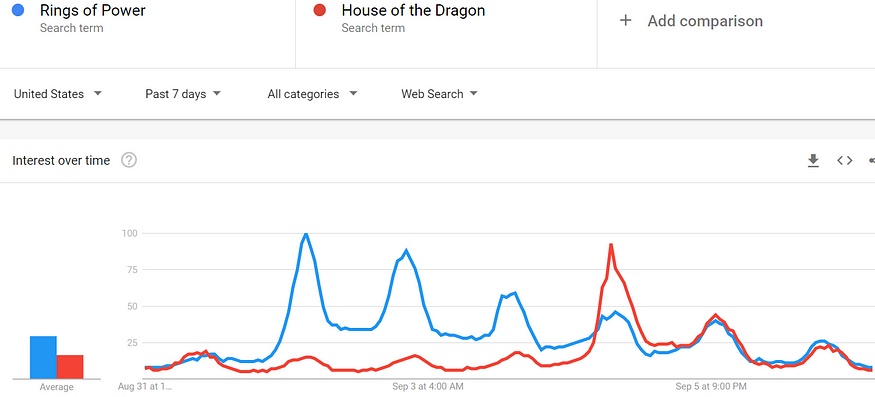

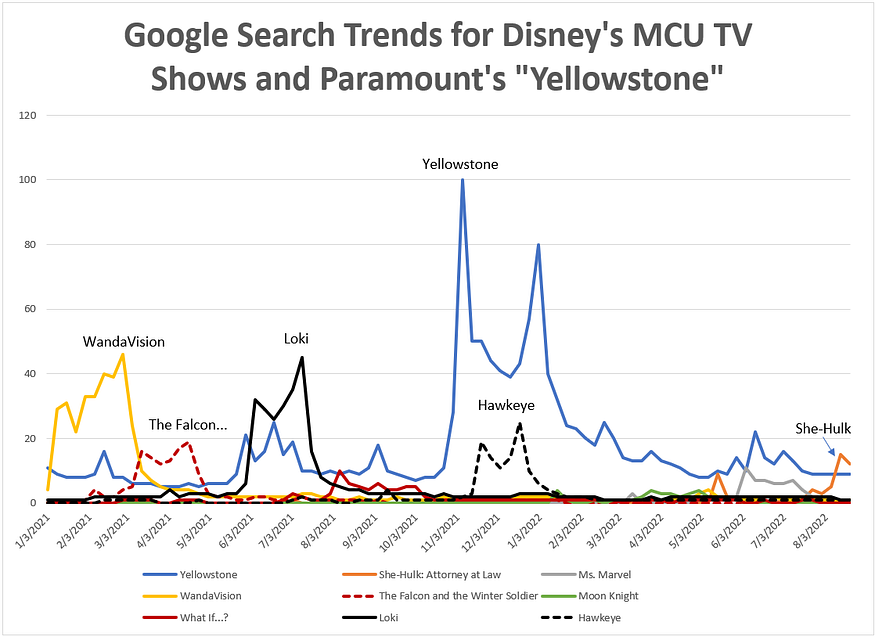

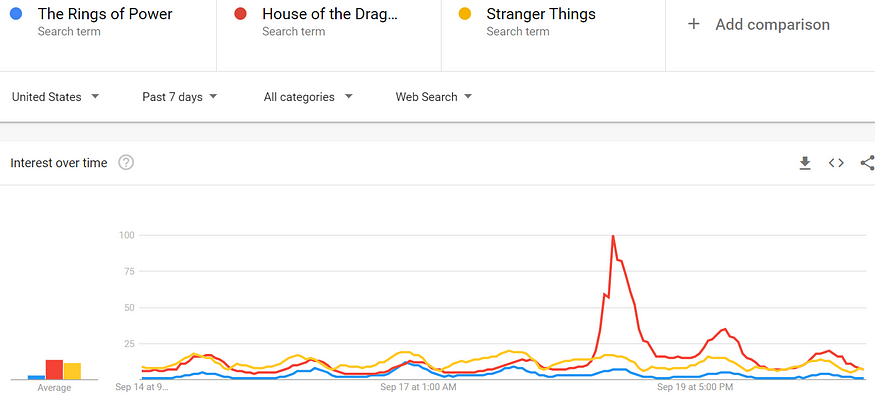

When looking at the last seven days of Google searches, it is especially depressing for Amazon (see Figure 3). What should be Amazon’s harvest-time for TRP — the time when its episodes are new relative to its competitors — is turning out to be its deathblow.

Figure 23: Google search trends for Stranger Things, The Rings of Power and The House of the Dragon (September 14 — 21, 2022)

TRP hasn’t caught on with audiences. That is indisputable.

But can TRP recover?

‘The Rings of Power’ is good television

I don’t do movie or TV reviews in this blog. It’s not my strength nor my interest.

However, I find it baffling why TRP is not as popular, if not more popular, than THD.

My wife and son, both J.R.R. Tolkien readers, are totally engrossed in the TRP story line. Galadriel, played by Morfydd Clark, wonderfully represents TRP’s protagonist. She isn’t just beautiful, she dominates every scene she occupies. [Although, I wish the TRP writers knew how to give her a sense of humor.]

Galadriel is very watchable.

But critics point out that Galadriel is little more than a Karen — a white woman perceived as entitled or demanding beyond the scope of what is normal or earned.

Even woke-friendly media outlets are questioning the quality of TRP:

“The creators of Amazon’s The Lord Of The Rings: The Rings Of Power know how to create spectacle, but they don’t know how to tell a good story,” writes Forbes’ Erik Kain.

Other than losing her brother, there is no character arc in the TRP narrative that suggests Galadriel has suffered (or lost) in any significant way to authenticate her intense anger and power in her quest to defeat the illusive Sauron.

Identity politics, right or wrong, has infected the critical debate as to whether TRP is a great TV show.

And without missing a beat in that depressingly shallow political debate, Amazon has launched a social media campaign suggesting critics of TRP are themselves ‘racists’ and ‘misogynists.’

In responding to online criticism of Amazon’s conscious decision to make TRP more racially diverse than director Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings movies, TRP’s creators offered this rejoinder:

“We, the cast of Rings of Power, stand together in absolute solidarity and against the relentless racism, threats, harassment, and abuse some of our castmates of color are being subject to on a daily basis.”

In my opinion, when you find yourself responding to ‘online critics,’ you have already lost the debate. Moreover, calling your core audience ‘racist’ is a losing marketing strategy.

Write a good TV show and people will show up.

Write a less-than-good TV show, and you are reduced to name-calling.

That seems to be where Amazon and the creators of TRP reside today.

It is unfortunate, because the Tolkien fans in my household (which does not include me) are enjoying TRP. My teenage son loves Galadriel. That is something to build on, yes?

What can Amazon do to undue the damage TRP’s creators have inflicted on a TV series that should have been one of the defining moments in streaming TV history?

For what it is worth, I believe TRP’s writers need to make Galadriel vulnerable. She is too strong and powerful without the proper backstory to explain it.

We need to see Galadriel suffer on a heartbreaking level.

Until that happens, I don’t think anybody is going to care what happens in the next TRP episode.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: kroeger98@yahoo.com