By Kent R. Kroeger (NuQum.com, September 27, 2019)

Acknowledging the news media is largely responsible for turning Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren’s into the leading challenger to Joe Biden in no way suggests she is not worthy. She is.

But it also reminds us that underestimating the power of the news media to play political kingmaker is unwise.

Some social theorists have even suggested that the nation’s most powerful elites control the political process by manufacturing consent through their control of the mass media.

Using the oft-cited Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky definition, manufacturing consent is the acceptance of government policies by citizens on the basis of incomplete information provided by the mass media; and, denying them access to conflicting information that might challenge the views of those in power.

No conspiracy theory is required in claiming that the cable news networks are manufacturing consent for the ascension of Warren to the Democratic presidential nomination. And we would be having this conversation about Kamala Harris instead, had it not been for the Tulsi Gabbard-spun black hole Harris disappeared into at the 2nd Democratic debate. The news media can make candidates overnight, and kick them to the gutter just as quickly.

As of today, there is one candidate whose rise stands out from the others.

Warren’s status as one of the top challenger’s to Biden is undeniable (she is the dark brown line in Figure 1) and highlights the equally indisputable fact that support for Bernie Sanders (blue line) has run aground at around 17 percent since May.

Figure 1: RealClearPolitics Poll Average for 2020 Democratic Nomination

Sanders came into this race at around 15 to 20 percent support among likely Democratic primary voters, the afterglow from his groundbreaking 2016 campaign against the Democratic Party establishment.

But how did Warren get to where she is in the polls?

If you believe her support is due to her progressive bona fides, political skills and charisma, you may be engaged in wishful thinking. Warren is not a great public speaker, is charisma challenged (certainly by Barack Obama standards), and has not proven herself to be adept at handling tough questions from the media.

Even her purported strength at generating progressive policy proposals is perceived by many progressives as merely building on ideas Bernie Sanders has been advancing for over 40 years. And her lone Senatorial legislative achievement, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, is at best a debatable accomplishment with few tangible results.

“Before presidential candidate Warren starts peddling the ‘success’ of her pet project on the campaign trail, she should consider how an agency that was formed under the guise of “consumer protection” has done more to hurt consumers than help,” argues Jeff Joseph, former head of domestic policy for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce from 1982 to 1997. “Since the bureau’s inception nine years ago, it has become one of Washington’s most unaccountable agencies.”

Still, as of today, Warren is in the strongest position to beat former Vice President Biden for the Democratic nomination. As to why she leads the opposition to Biden is a legitimate question that deserves a quantitative answer.

Warren is a business law and policy expert, as she has demonstrated in the debates

Warren’s deep knowledge of economic and financial policy makes her a formidable presidential candidate, particularly on a debate stage. Bernie Sanders’ own senior economic adviser, Professor Stephanie Kelton, better known for her advocacy of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), praises Warren for her ability to explain why Sanders’ signature proposal — Medicare for All — would likely result in a net decrease in the financial burden of healthcare for the vast majority of U.S. households.

“Warren does an extremely good job keeping the focus on total costs,” Kelton tweeted recently. “We already pay more than anyone in the world, and we pay more than we will end up paying (collectively) under Medicare for All.”

Yet, Warren’s ability to cogently explain the benefits of Medicare for All over our current system only frustrates progressive Democrats who feel betrayed by Warren’s reluctance to make a firm commitment to Bernie’s plan. Twitter gadflies have been out in force questioning Warren’s commitment to progressive ideas.

Kyle Kulinski, a progressive favorite in the podcast sphere, recently detailed his reasons for distrusting Warren, citing, among other things, her willingness to court Wall Street and business executives even as she professes that she will hold Wall Street “accountable” and stop the “main sources of Wall Street looting.”

“One candidate (Warren) waffles on Medicare for All and the other one (Sanders) never has,” Kulinski told his podcast audience. “That tells me she’s less likely to pursue it, and even if she does pursue it, it is unlikely she’s gonna waste a lot of political capital and go to the mat to try to get it implemented.”

The ambivalence of some progressives towards Warren brings to the fore her internal contradictions. Warren, a former Harvard business law professor and registered Republican until 1995, creates genuine angst among Wall Street power brokers when she talks about banking reform with level of authority few others in the Democratic nomination race can match. At the same time, Warren, the politician, is actively telling Democratic Party leaders she wants to work within the current political-economic system, not do a complete overhaul to the extent advocated by Sanders.

In that sense, Warren is cast in the same mold as Barack Obama — an incrementalist at her core — and her rise in the polls has seemingly coincided her growing number of public overtures to former Hillary Clinton and Obama supporters.

Not all candidates benefit from more media coverage — but Warren does

Despite a concerted effort from some progressives to stunt the Warren surge in the polls, the reality is that she is rising faster than any other candidate for the Democratic nomination.

What is the explanation?

Using aggregated polling data from RealClearPolitics.com and cable news coverage data from The GDELT Project, an open source platform that monitors the world’s news media, we uncover evidence that changes in cable news coverage of Warren predicts changes in Warren’s popularity. Whereas, changes in Warren’s popularity does not predict changes in the volume of Warren’s cable news coverage.

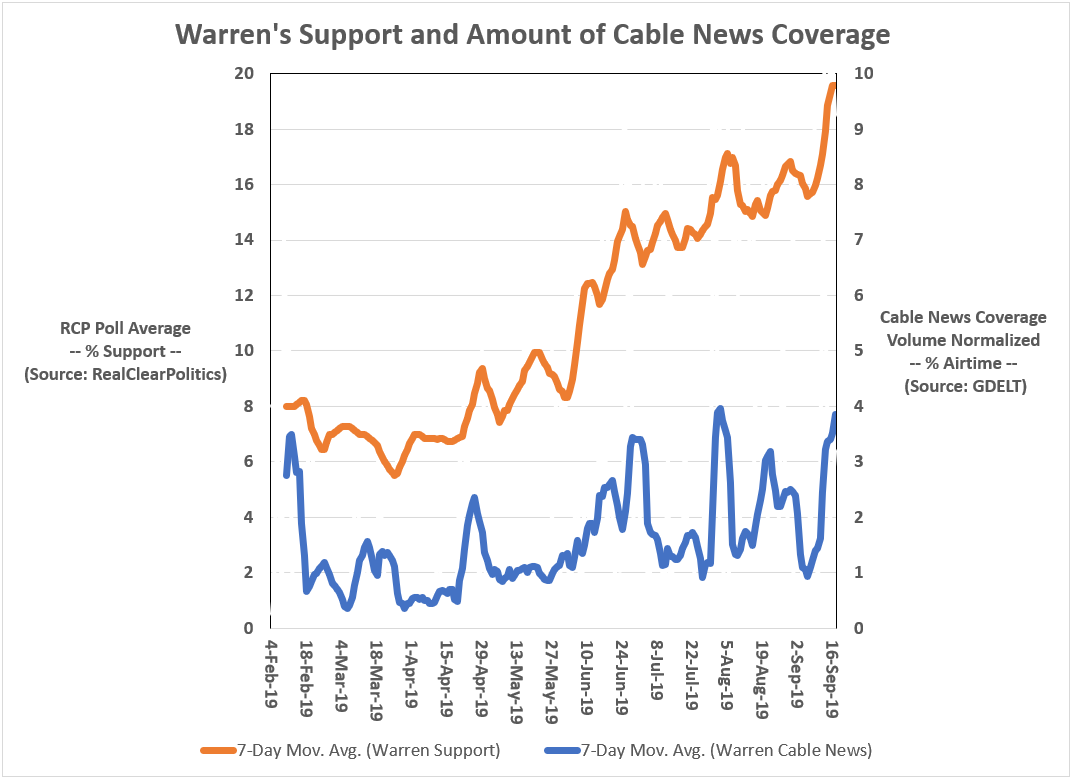

Figure 2 shows how spikes in Warren’s public support track line up with spikes in the relative amount of cable news coverage she receives.

Figure 2: Tracking Warren’s Public Support and Cable News Coverage

Figure 3 summarizes Warren’s public support and the relative volume of her cable news coverage by plotting their relationship — which we can see is very strong (the two-variable regression model accounts for nearly half of the variance in her public support).

Figure 3: Relationship between Warren Support and Cable News Coverage

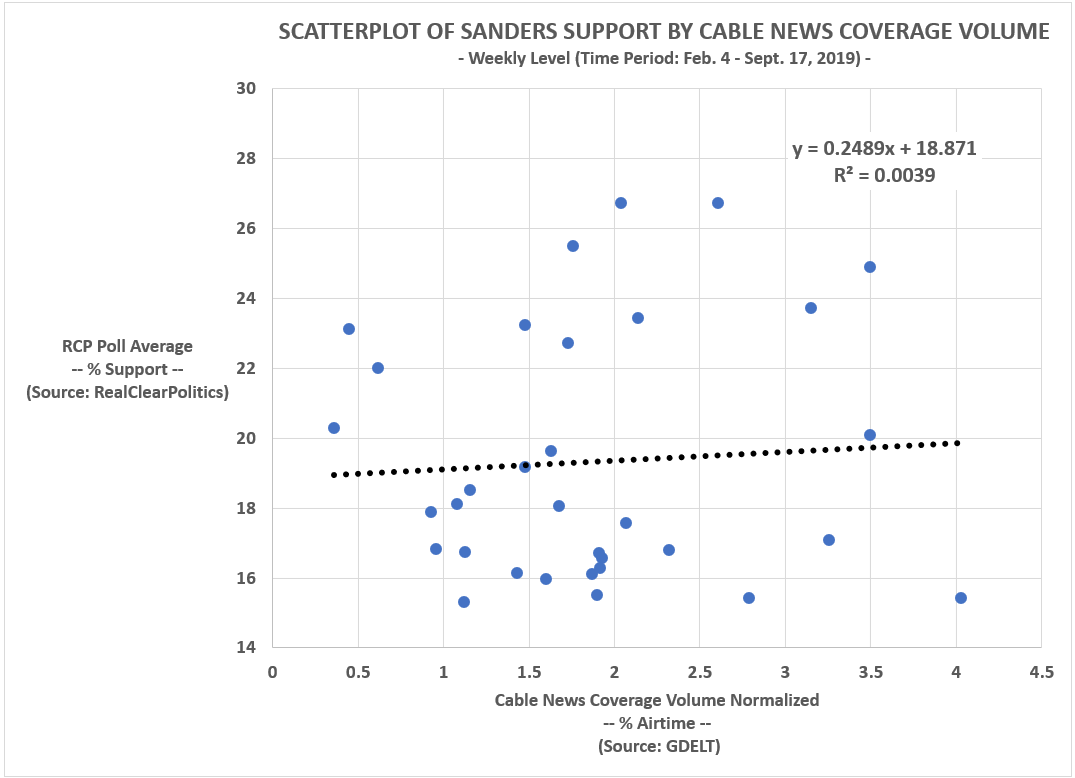

Contrast Warren’s data with the same variables measured for Sanders (see Figure 4). His scatterplot shows no discernible relationship between his public support and cable news coverage. Why would they be related so strongly for Warren and minimally for Sanders?

The quick answer is that Sanders, having run in 2016, is a known quantity and likely 2020 voters do not rely as heavily on news coverage to form attitudes about Sanders — in other words, their views on Sanders may already be firmly established.

Figure 4: Relationship between Sanders Support and Cable News Coverage

While Figures 2–3 indicate substantial common variation between Warren’s public support and cable news coverage, the graphs tell us little about the causal direction. Which causes which? Are they even related once other factors are considered?

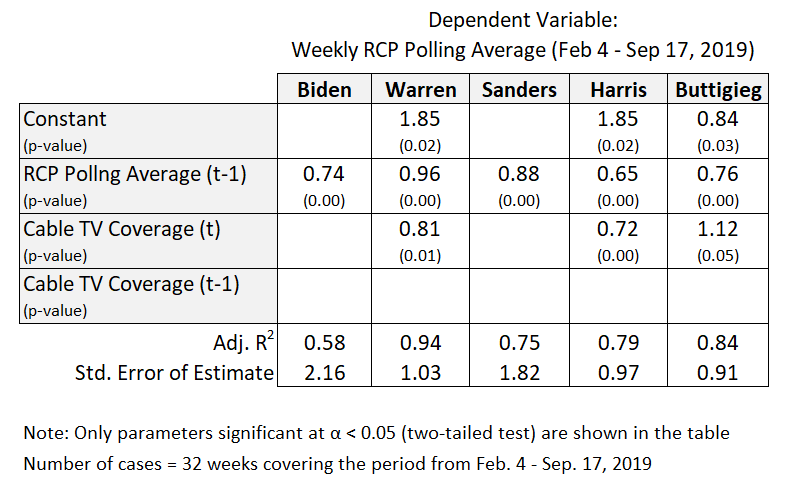

Figure 5 is an initial step in trying to answer those two questions. After aggregating the daily data for public support (% support according to RealClearPolitics poll average) and the relative volume of cable news coverage (% of airtime) to the weekly-level, I estimated for each of the top 2020 candidates (Biden, Warren, Sanders, Harris and Buttigieg) a linear regression model explaining public support as a function of past values of public support (t-1) and cable news coverage (at time t and t-1). The linear models are summarized in Figure 5.

The first finding is that public support and the volume of cable news coverage are not related for the best known candidates entering the 2020 race (Biden and Sanders). However, for Warren, Kamala Harris, and Pete Buttigieg, their share of cable news coverage is contemporaneously related with their public support levels.

Figure 5: Does the Volume of Cable News Coverage Relate to Candidate Popularity?

It is also notable that these linear models explain a significant percentage of the total variation in public support, particularly for Warren, Harris and Buttigieg.

Nonetheless, in Figure 5, we still cannot talk causation as the statistically significant relationships between cable news coverage and popularity are all contemporaneous. As we learned in First-Year Statistics, correlation is not causation. Instead, we need time-ordering: When ‘X’ happens at time t, ‘Y’ happens at time t+1, all else equal.

To see the time-order effects, I estimated a vector autoregression (VAR) model using the same variables as in the linear models, but at the daily level and after a first-difference transformation to render all variables stationary. More simply, I compare the day-to-day change in cable news coverage to the day-to-day change in popularity, and vice versa.

And it is here where we finally see the causal path for Warren.

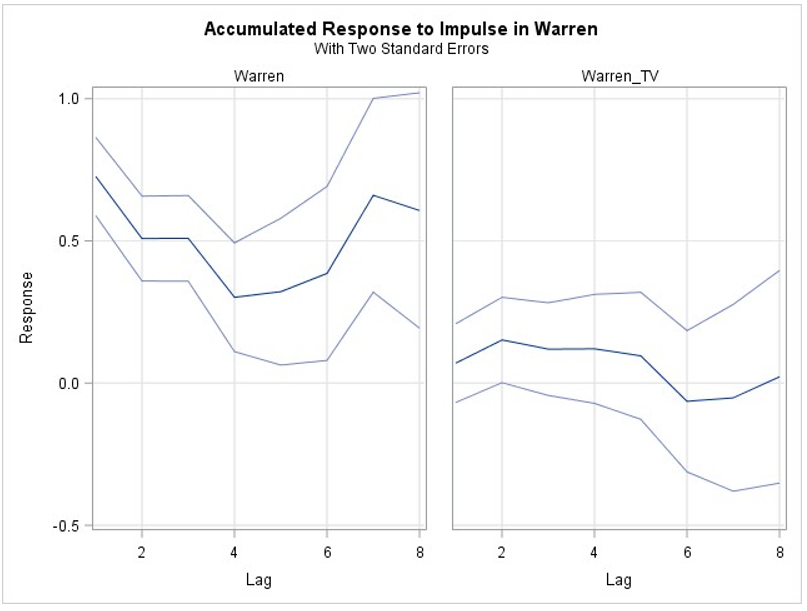

The left-hand graph in Figure 6 displays the impulse response function for the accumulated impact of a one-unit impulse in cable news coverage (1% of total cable news airtime) on Warren’s public support (% support). The graph plots the estimates over seven days subsequent to the impulse. The middle line is the estimate and the outer lines represent two standard deviations above and below the estimate.

According to the VAR model for Warren, a one percentage-point increase in her share of cable news coverage results in a 0.25 percentage-point increase in support for Warren among likely Democratic primary voters by the 3rd day after the impulse.

That may not seem like a lot, but consider that Warren’s support has grown 14 points over a six-month period (March — September) from 7 percent to 21 percent — that is an average increase of 0.08 percentage-points-a-day.

Figure 6: Response of Warren Public Support to Impulses in Cable TV Coverage

Figure 7 is similar to Figure 6, except it is the right-hand-side plot that most interesting as it displays the accumulated impact of a one-unit impulse in Warren’s popularity (1% percentage-point in RCP poll average) on changes in Warren’s cable news coverage (% of cable news airtime). According to the Figure 7, changes in Warren’s popularity on her cable news coverage hover around zero.

Figure 7: Response of Warren Cable TV Coverage to Impulses in Warren Public Support

For Warren, the causal path between public support and news coverage is recursive (i.e., moves in one direction), flowing from news coverage to public support.

And, while the effect is relatively small for any single shock in Warren’s news coverage, over a span of months the total effect can be significant, particularly if large spikes are more likely to be positive than negative — which they have been for Warren.

Since February, Warren has experienced 12 days where the spike in her cable news coverage exceeded +2 percentage-points of all cable news airtime, compared to only six times where it was less than -2 percentage-points — a two-to-one ratio. In contrast, Biden has experienced 70 instances with spikes of those magnitudes, 35 positive and 35 negative, for a one-to-one ratio. Sanders, like Biden, also has a near one-to-one ratio in positive-to-negative cable news coverage impulses.

Interestingly, like Warren, Harris has also witnessed twice as many large positive impulses as negative ones, which is consistent with a common refrain among Sanders supporters that the news media favor both Harris and Warren over Bernie. Figure 8 supports that conclusion.

FIgure 8: Number of Large Daily Impulses (“Spikes”) in Cable News Coverage between Feb. 4 to Sep 17, 2019

Manufacturing consent or evidence Warren is the best candidate?

If Warren were the “best” candidate to challenge Biden, wouldn’t we expect some causal flow from public support to cable news coverage, as that would indicate an independent basis for Warren’s growing popularity?

On the other hand, the data here is consistent with the notion that, out of practical necessity, the news media mediates the public’s exposure to political candidates. It isn’t that the media has some nefarious agenda to make one person the next president; but, rather, the reality of a geographically large country where most people learn about political candidates directly through the media or indirectly through other people that follow politics in the media.

It doesn’t require referencing the manufacturing consent thesis to explain why Warren (or Harris or Buttigieg) might gain more positive coverage in this election cycle than some other candidates that came into the election better known. They are the new kids on the block with the most big donor money coming out of the gate.

It is hard to imagine, however, cable news journalists, producers and executives doing their jobs without imprinting, in the aggregate, their collective judgments and biases into the news when deciding how much to cover some candidates over others.

Neither is it extraordinary or subversive to assert the news media introduces an inordinate amount of influence and institutional bias into the selection process. The mass media controls what most of us see and hear about presidential candidates. Unless you live in Iowa or New Hampshire, you are probably not going to meet a candidate in person during this election cycle — and certainly not going to have a long, interactive conversation with them on tax or trade policy.

And since we get our information through the mass media, it is the mass media that can make or break anybody running for president (except, apparently, Donald Trump — a media creation that got out-of-control).

As former Bill Clinton political strategist James Carville once said, “You can’t turn a frog into a prince, but you can make them president.” [Carville was not sufficiently woke in the early 1990s to add princesses to his assertion.]

Members of the national news media rarely apologize for their gatekeeper role in the presidential election process. Many journalists, in fact, believe they are the most qualified and objective to make the decisions as to which candidates should be covered extensively (Elizabeth Warren) and which candidates can be ignored (Seth Moulton — Who? — Exactly).

“To the degree that media attention causes a candidate to become more popular, there’s a winner-take-all effect here: The leading candidate will get the most coverage, boosting their lead. Meanwhile, the media has the potential to trap a candidate in last place because they can’t get the coverage they would need in order to rise in the polls,” writes Jonathan Stray, a journalist and computer scientist who teaches computational journalism at Columbia. “But what’s the alternative? Should journalists cover every candidate equally? It’s ridiculous to imagine journalists struggling to reach story quotas, so that each candidate gets the same amount of press.”

The bottom line, according to Stray, is that journalists and producers are the most logical and qualified gatekeepers to decide who gets covered and how much they are covered. They are not perfect, but they are better than the alternatives, says Stray.

In a less hyper-partisan world, Stray might be right. But isn’t it equally ridiculous to have talking heads like CNN’s Chris Cillizza saying the current Democratic nomination race is down to TWO candidates, when quite obviously the statement is false? (See Figure 1 above.)

There are too many anecdotal examples of cable news on-air talent offering blatantly false or misleading information about candidates — so many, in fact, that trying to summarize them here would be overwhelming.

Nonetheless, the mass media does have the power to change candidates’ fortunes, independent of other factors (e.g., debate gaffes and other unpredictable events). Elizabeth Warren may be deserving of her top challenger status, but she likely realizes she wouldn’t be in this position had the cable news networks not helped her get there.

- K.R.K.

All comments and complaints can be sent to: kroeger98@yahoo.com

Data used in this essay are made available on GitHub at: https://github.com/Nuqum/SEP2019_VARanalysis.git