By Kent R. Kroeger (NuQum.com, September 20, 2019)

________________________________________________________________

The following is the second of two essays about the Electoral College and the initiative to replace it with the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC). The first essays focused on arguments by the Founding Fathers in support of the Electoral College — particularly the writings of James Madison and Alexander Hamilton in The Federalist Papers. The second essay focuses on the NPVIC and details some of its problems (and virtues) relative to the Electoral College and suggests a compromise system — the congressional district method — already employed in Nebraska and Maine.

________________________________________________________________

The Electoral College (EC) was not embraced by the Founding Fathers as a way to encourage the broad geographic support for an elected president. Had that been the case, they would have given each state an equal number of electors.

They did not do that. Instead, they allocated electors based on population size with a small compromise to smaller states by giving them at least three electors.

Yet, today, one of the justifications for keeping the EC is that it encourages presidential candidates to pursue broad, geographically-dispersed support. Hillary Clinton’s failure in 2016 was largely due to her inability to do exactly that.

Independent of the Founding Fathers’ intentions, it is an admirable goal to expect presidential candidates to appeal across a broad section of American society and not simply win the presidency predicated on an attraction to an urban and coastal constituency. Middle America deserves a president’s attention and loyalty.

On the the hand, Middle America should never be able to hold the rest of the country hostage to its specific interests. This is the heart of the EC versus popular vote debate.

Democrats may want to reconsider eliminating the Electoral College

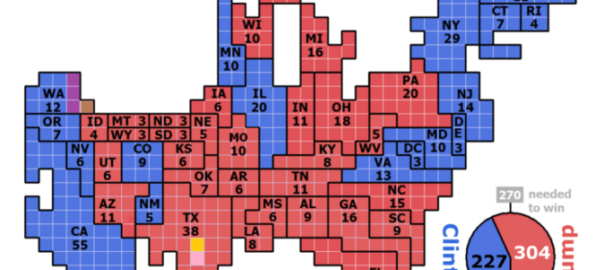

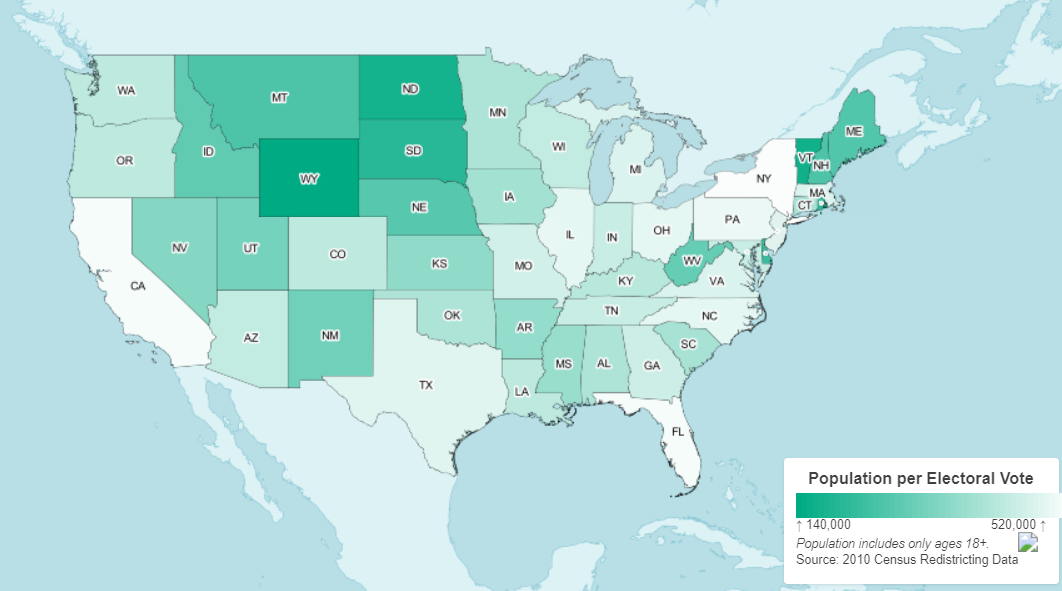

These two facts are often mentioned first when political scientists and commentators discuss the Electoral College: The Electoral College (EC) gives disproportionate weight to low-population states (see Figure 1), and the EC’s state-level, winner-take-all method (with the exception of Nebraska and Maine) frequently distorts the popular vote difference.

Figure 1: Population per Electoral Vote (2010 Census Data)

A third characteristic of the EC is less frequently mentioned: it is impossible for a coalition of low-population states to impose their will on the rest of the country. If every small state were to allocate their electoral votes to one candidate, that candidate would still need Washington, Virginia and New Jersey to secure an electoral victory. Those are hardly small, rural states.

Conversely, large states could impose their will on the country if California, Texas, New York, Florida, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio, Michigan, Georgia, North Carolina and New Jersey were to stand behind the same candidate. Hopefully, it is not lost on the Democrats that they electorally dominate in four of those states (CA, NY, IL, NJ) and are highly competitive in five others (Florida, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, and North Carolina).

And if demographic trends continue, Georgia and Texas will both be majority-minority states by 2036 and more politically competitive than they are now.

The irony of the current push by Democrats to abolish the EC is that, if there is a partisan advantage in the Electoral College, it is with the Democrats.

The Electoral College nurtures narrow, sectarian interests

But there are other reasons to eliminate or modify the EC, unrelated to partisan bias. The winner-take-all nature of the EC distorts state-level voter preferences and puts too high of a premium on states where the two parties are competitive (battleground states). For any given election, the number of battleground states typically varies between 10 and 15 states.

It is not an exaggeration to say, due to the EC, the U.S. has never had a true national election for president, but only battleground state elections. The other states are irrelevant, as we saw in 2016 by the states Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton spent most of their money and time. Fifty-three percent of campaign events for the Trump and Clinton campaigns in the two months before Election Day were in just four states: Florida, Pennsylvania, North Carolina and Ohio.

Battleground states often have their own idiosyncratic interests, independent of a common national interest (assuming that concept exists). Arguably, Trump’s trade war with China is more a function of the interests of working-class voters in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Ohio than of the interests of the nation as a whole. In that sense, the EC may have contributed to current U.S. trade policy towards China.

But candidate appeals to sectarian interests occur in popular vote elections too, right? Successful politicians often offer policies and campaign promises to specific subgroups in the hope of building a winning popular vote coalition.

The difference is, in a popular vote election, every voter is as valuable as any other voter (though some are more expensive to reach or persuade than others — more on that later). At least in theory, in a popular vote election every voter is a potential target for a candidate’s coalition. In a battleground state election, most non-billionaire voters are at the outset eliminated from ever receiving serious attention from the candidates (I’m talking about states like New York and California).

Going forward, an Electoral College victory might be the only path for the GOP

In a report published last year for the Brookings Institute, Rob Griffin, Ruy Teixeira, and William H. Frey segmented the U.S. population into 32 demographic groups. Forecasting county-level compositions for these segments over time, the researchers were able to generate multiple simulations of the presidential vote in future elections (2020, 2024, 2028, 2032, and 2036) using 16 different voter turnout and support scenarios relative to 2016 (e.g., Equal turnout by race, Black turnout or support like 2012, White non-college-educated voters swing to +5 pts. to Democrats, etc.).

They had a remarkable finding for the 2020 election. Of the 16 scenarios they tested, only one resulted in the Republican presidential candidate winning both the popular vote and Electoral College (Scenario: White non-college-educated voters swing +5 pts. to Republicans relative to 2016). All else equal, according to this research, Trump needs to amp up whatever he did to attract White, non-college-educated voters in 2016. [If you follow Donald Trump at all, doesn’t it feel like that is exactly what he is doing?]

There were, however, three other scenarios where the Republicans could lose the popular vote and still win the Electoral College (EC): (a) Hispanic, Asian, and other races swing +7.5 points to Republicans, (b) white college-educated swing +5.0 points to Republicans, and (c) white college-educated swing to Democrats (+2.5D and -2.5R) while white non-college-educated swing to Republicans (+2.5R and -2.5D).

It is no surprise the Democrats are the most eager to scuttle the EC. With the likely demographic and socioeconomic changes in the future, the only way the Republicans win the White House is through the EC.

Write Griffin, Teixeira, and Frey:

“Republicans face a clear need to enhance their appeal to America’s rapidly growing communities of color — especially Hispanics and Asians. If they do not, Republicans risk putting themselves into a box where they become ever more dependent on a declining white population — particularly its older segment. As the simulations show, GOP electoral fortunes could be linked to a strategy where they repeatedly lose the popular vote but, based on larger advantages among white — particularly white noncollege-educated — voters, pull the electoral vote rabbit out of the hat anyway. This could work for a time, though ultimately it, too, would be undermined by shifting demographics. The prudent course may very well be to adapt now, rather than later, to onrushing demographic change. If nothing else, it would give the party more options going forward.”

The EC threatens the legitimacy of our nation’s highest office. We cannot weather another election like 2016 in which the perception was the winning candidate, Donald Trump, won despite losing the popular vote.

Democratic presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren offered a CNN town hall audience in Jackson, Mississippi perhaps the most common argument against the EC when she told them: “We need to make sure that every vote counts…My view is that every vote matters. And the way we can make that happen is that we can have national voting and that means get rid of the Electoral College.”

That’s really what this debate comes down to: The popular vote counts every vote equally and the EC does not.

If only that were true.

A national popular vote is misrepresented by its advocates

New York Magazine’s Eric Levitz mocks EC apologists when he mimics their evidence-free argument: “Abolishing the Electoral College would definitely have this bad effect, for reasons so logically sound I don’t need to provide evidence for them (even though other defenders of the Electoral College insist it would have the opposite effect, which would also be bad).”

Unfortunately, popular vote advocates aren’t much better. Beyond the intuitive logic that ‘every vote should count the same,’ they ignore the inherent problems in implementing a national popular vote when our federal system allows each of the 50 states to implement their own voting laws and procedures.

At least France, a country that employs a national popular vote to elect their president, implements uniform election laws and procedures across its 36,000 communes. The legitimacy of French presidential elections resides, in large part, to the homogeneous nature of their electoral process. The U.S. democracy lacks that essential feature.

Two aspects of a national popular vote are widely misunderstood by its proponents. For one, we’ve never had a popular vote election in this country; therefore, it is not fair to compare the popular vote with the EC result within any particular election. Hillary Clinton did not actually win the popular vote in 2016 — there was no decipherable popular vote in 2016 (or any U.S. presidential election before that).

Campaign strategies and expenditures would fundamentally change in a popular vote election. There is no better example than the 2016 election. California had no competitive statewide races between a Democrat and Republican in that election.

This matters because partisan differentials in voter turnout are affected by the presence (or lack thereof) of competitive statewide races. Unless a California Republican voter had a competitive local or congressional race to draw them into the voting booth, a higher percentage than normal of California Republicans stayed home on Election Day 2016. The data say as much.

Washington Post senior political reporter, Aaron Blake, noted after the 2016 election:

“The Senate race in California featured two Democrats, and there wasn’t another statewide race featuring a Republican, except for president (which was a foregone conclusion). In other words, there perhaps wasn’t as much reason for Republicans to turn out to vote. Did this depress GOP turnout? Maybe. In 2012, exit polls showed Republicans were 27 percent of the state’s electorate; this year, they were 23 percent.”

Besides fundraising, the 2016 EC election offered little incentive for either Clinton or Trump to campaign in California. As money and a candidate’s time is a finite resource in any political campaign, it is a waste of resources to spend to focus on a strongly partisan state.

In a popular vote election, however, the incentives change dramatically, particularly for candidacy like Trump’s, who would have needed to shore up his support in historically strong Republican strongholds in California, such as Orange County.

As it was, Trump and the Republicans did not dedicate serious resources to California in 2016 and the state GOP suffered in the voting booth.

The second misunderstanding about the popular vote is the assumption that since every vote counts the same — that is, offers an identical benefit to a candidate — all votes must therefore be of equal value.

But as economists tell us, an item’s value is its benefit minus its cost. In a popular vote election, some votes will still be more valuable than others to a presidential candidate. Why? Because candidates pay attention to the costs associated with mobilizing and persuading voters. For example, some voters are isolated geographically, requiring significant campaign investments to mobilize them. Voters can also have strong loyalties to another party/candidate, thereby lowering the return-on-investment if a candidate wants to persuade them to defect to a different party/candidate.

While the variation in value across voters might be greater within the EC system, this variation doesn’t go away with the popular vote: Some votes will be more cost-effective to pursue.

This feature of the popular vote was revealed in 2008 research conducted by Stockholm University economics professor David Strömberg, who assessed the impact to campaign strategy if the U.S. we’re to convert to a popular vote.

Using state-level presidential election data from 1948 to 2004, Strömberg estimated the effects on campaign behavior (visits) of a direct national popular vote for president relative to a EC election and his findings are summarized in Figure 2 (below). His findings were revealing.

In Figure 2, states above 1 on the y-axis receive more than average visits per capita under the Electoral College system, whereas states to the right of 1 on the x-axis have more visits per capita than average under the Direct Vote system. Therefore, states in the lower-right-hand quadrant will most likely benefit from candidate increased attention should the U.S. adopt a popular vote system.

Figure 2: Equilibrium visits per capita and advertisements, relative to national average (Electoral College versus National Popular Vote)

One finding from Figure 2 is that a direct popular vote still results in significant variation across states in the amount of attention (visits per capita) they receive from presidential candidates, though less than under the EC.

Nevertheless, some states, such as Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New York, and New Jersey, will benefit from a popular vote system. According to Strömberg, “Because of their average partisanship, these states are rarely competitive when the national election is close. Consequently, they do not receive much attention under the Electoral College system. Still, these states have quite a few marginal (swing) voters, making them attractive targets under Direct Vote.”

A popular vote election will replace the incentive for candidates to concentrate of a small set of battleground states with an increased incentive to mobilize voters where the population is highly-concentrated, particularly if includes an above average proportion of “swing” voters.

If Strömber is correct, a popular vote system may not significantly impact the amount of attention candidates pay to California, as its swing voter density is not as high as in some other areas. Instead, campaigns will prefer to use their financial resources and candidate time in areas with a higher return on investment.

The Electoral College is vulnerable to error and fraud, but the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact isn’t an improvement

The Founders did not think much of direct democracy, and even if the Republicans do operate a nominating process prone to elevating populist, heterodox candidates, it still doesn’t preclude replacing the Electoral College with something more democratic like the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC).

The NPVIC would require signatory states to cast their state’s electoral votes for the candidate who won the national popular vote, even if a plurality of their voters preferred a different candidate. The compact won’t be invoked until states with 270 electoral votes among them have opted in.

Principally advanced by Democrats in order to circumvent the long process of passing a constitutional amendment, the NPVIC has secured the support of 16 states and two more whose legislatures are likely to pass the NPVIC soon, for a total of 206 electoral votes (see Figure 2). Only 64 electoral votes more to go. Unfortunately for NPVIC advocates, those last 64 will not be easy to secure as it will require all of the remaining states that are not Republican strongholds to pass the NPVIC: Michigan, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wisconsin. As of today, all have a lower and/or upper legislature controlled by the Republicans.

Figure 2: Population sizes and growth of NPVIC and non-NPVIC states

Also working against the NPVIC is its potential constitutionality, as it ‘trades away’ a person’s vote in one state based on voter preferences in other states. Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 in the Constitution places the power in allocating electors to the states (which is consistent with the NPVIC); but, the 14th Amendment (Section 2) explicitly states that when a vote is “in any way abridged,’ the state’s representation in the U.S. House (and, by extension, the Electoral College) can be reduced proportionately.

The Fourteenth Amendment (Section 2):

“Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the inhabitants of such State, being eighteen years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such citizens shall bear to the whole number of citizens eighteen years of age in such State.”

For example, if the majority of Florida voters vote for the Republican candidate but the Democrat wins the national popular vote, all of Florida’s 29 electors would be given to the Democrat under the NPVIC, thereby abridging the votes of roughly half of Florida voters. At risk could be half of Florida’s 29 electoral votes if a federal court determines 14th Amendment rights were violated under the NPVIC voting trading arrangement.

Adding some perspective might help before we completely upend an Electoral College that has, most of the time, worked as designed.

Since 1789, out of 58 presidential elections, only four (1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016) have produced winners in the Electoral College who received fewer popular votes than another candidate. And the 2000 election is debatable if it should be included on that list. Had Florida captured and counted votes accurately, Al Gore likely would have won both the Electoral College and popular vote in 2000.

The argument can still be advanced, however, that the Electoral College makes U.S. presidential elections prone to manipulation, by foreign or domestic sources. The 2016 election is a testament to our electoral vulnerability to small, concentrated shifts in statewide popular votes. Trump won three states (Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin) by a total of 78,000 votes (a half of a tenth of a percent of all votes cast), shifting the Electoral College by 46 electors. A targeted shift of 39,000 votes would have changed the final outcome.

If ever there is an argument for the popular vote, isn’t that it? Well, maybe and maybe not. Where the winner-take-all nature of the Electoral College amplifies the risk for some types of vote manipulation, the popular vote invites others.

Let’s start with the best argument for why the Electoral College needs to be modified or replaced: The 2000 Florida vote. An election where George W. Bush and Al Gore were separated by 537 votes after an incomplete, deadline-constrained recount tally. We will never know the true preferences of Florida voters in that presidential race.

Not only did the vote capturing methodologies in Florida vary by county (some using the infamous “butterfly” ballots, others using “bed sheet” ballots, and still others using computer touch screens.), the recount was limited to a small set of counties and even that process was interfered with by a series of stunts and intimidation tactics by the now infamous Roger Stone of election 2016 fame.

The questionable validity of Florida’s 2000 result would have been mitigated in a popular vote election, the 537-vote difference no more than a historical footnote, forgotten within days. That is the irresistible attraction of the popular vote.

Yet, there are modifications to the Electoral College that also could avoid the 2000 Florida fiasco. For example, if presidential electors were earned based on each congressional district vote (akin to what Nebraska and Maine do today), Florida’s incompetence could have been isolated to one congressional district, not the state’s entire slate of electors.

But a popular vote might have its own problems, potentially as paralyzing and contentious as the 2000 result.

If the objective of the popular vote is to capture the precise, unbiased preferences of the voting population, its validity is already compromised if the voting methods and procedures vary across states and, within states, by counties. A national voting methodology would need to be established where state voter registration laws are uniform and vote capture, processing and tabulation standards are consistent, secure, and auditable at the voter-level.

A recount in a national popular vote election would invite chaos and threaten the election’s legitimacy

In a national popular vote election, every vote is counted and weighted the same (a good result), but each vote also becomes contestable (potentially a really, really bad result). One feature of the Electoral College is that it can handle significant amounts of error (e.g. voting machine errors, voter fraud), the 2000 election being an exception. A close vote within a single state only becomes relevant if that state’s electoral votes determines the election’s outcome.

But imagine a close, contested national election under a popular vote system where the losing candidate (or party) calls for a recount. For an instant-gratification society expecting final election results no later than the next day, it could take weeks to complete a national recount. Where one state (Florida) held up the 2000 result for over a month, a recount in 50 states (plus D.C.) could hold up a contested popular vote election for much longer. Do we recount all 140 million votes, or a selection based on fraud complaints, or do we draw a probability sample of votes? Who coordinates the process? Who makes the critical decisions during the recount?

For better or worse, the Electoral College has most likely papered over vote fraud that may have occurred over our nation’s history, in part, because we’ve rarely had presidential elections close enough to warrant much attention to its existence (the 1960 Nixon-Kennedy election being one of the exceptions; though, in that case, it is hard to distinguish myth and reality with some of the alleged stories of vote fraud from that election).

A recount in a popular vote election has other problems too. Instead of one Roger Stone trying to muck up a vote recount in a few counties in Florida, you could have hundreds of little Roger Stones trying to disrupt the recount from coast-to-coast. The presidency is too important and the incentives too great not to expect an extraordinary level of effort, above and below board, by both parties to ensure they get the outcome they want.

Campaign activities, such as ballot harvesting, introduce significant opportunities for fraud

Add one more complication to a national popular vote election. U.S. elections are implemented at the state-level. We are not France. The U.S. has never held a national election. Rather, we hold 50 different state elections — each state with its own rules and procedures.

State laws on voter registration (e.g. registration at DMV, etc.), voting methods (e.g., vote-by-mail, etc.) and the types of allowable campaign activities all vary across states. None more potentially game-changing in a national popular vote than the practice of ballot harvesting — a campaign activity in which party activists/volunteers collect absentee ballots from specific voters and drop them off at a polling place or election office.

Ballot harvesting is illegal in some states (e.g., North Carolina and Texas) and legal in others (e.g., California and on a limited basis in Arizona). Conceptually, the activity sounds harmless. Just another get-out-the-vote (GOTV) practice that facilitates voting for the elderly, chronically ill, and people otherwise unlikely to vote. What could be wrong with that? Getting more people to vote is a good thing. Evangelical Republicans in Iowa have been busing their constituents to polls for decades with barely a complaint from the Democrats. Why should picking up sealed absentee ballots cause a ruckus?

For one, the practice has already become a new partisan battleground — nowhere more so than California where the Democrats have exploited the nation’s most permissive ballot harvesting law and taken it to an industrial scale in the 2016 and 2018 elections.

Speaking at a post-election forum soon after the 2018 midterm elections, House Speaker Paul Ryan said of the California ballot harvesting law: “California just defies logic to me. We were only down 26 seats the night of the election and three weeks later, we lost basically every contested California race. This election system they have — I can’t begin to understand what ‘ballot harvesting’ is.”

Trump lost the national popular vote to Clinton by 2,868,686 votes in 2016, but lost to her in California by 4,269,978 votes. Take away California, Trump won the popular vote in the 49 other states (plus D.C.) by 1,401,292 votes. Making it more frustrating for Republicans, as Speaker Ryan’s comments suggest, almost all of Clinton’s popular vote advantage occurred in the weeks following the Election Day tally when many of California’s absentee ballots began to arrive in election offices.

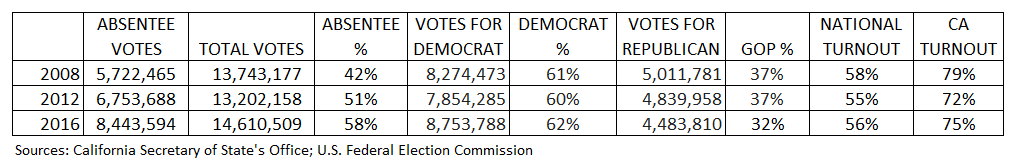

As Figure 3 shows, absentee voting has become a significantly larger element in California presidential-year elections since 2008. Absentee voting accounted for 58 percent of all California votes in 2016, up from 42 percent in 2008.

Figure 3: California Absentee Voting Statistics (2008, 2012, 2016 presidential elections)

Regardless, it is not clear (at least at the presidential-level) that the increase in absentee ballots related to a greater vote share for Clinton, who received 62 percent of the California in 2016 compared to Barack Obama’s 61 percent in 2008 and 60 percent in 2012. If anything, third party candidates may have been the primary beneficiaries of the increased absentee voting in California as votes for the Republican presidential candidate fell from 37 percent in 2008 to 32 percent in 2016.

The question remains: Is ballot harvesting an effective way to boost turnout rates or a prime opportunity for ballot fraud? Most evidence points to the former. Yet, Speaker Ryan’s reaction to the practice in 2016 echoed other Republicans who were more direct, suggesting the Democrats are doing something improper. A common concern voiced about ballot harvesting is that the chain of custody for mail-in ballots does not go directly from the voter to election officials — a party activist handles the ballot a significant portion of its journey from the voter to the election office. What could go wrong with that?

A lot.

In 2016, there was one notable case of alleged election fraud involving ballot harvesting. But it wasn’t a Democratic campaign operation, but a Republican one — Republican Mark Harris’ campaign in North Carolina’s 9th District (which was recently recontested because of that fraud). Among the alleged crimes included a Republican operative collecting ballots from historically Democratic areas and discarding them.

Arizona recently passed a law strictly limiting ballot harvesting after one witness testified about finding thousands of completed ballots in a Yuma garbage dumpster, and another detailed a case where poll workers did not properly label collected ballots, thereby circumventing a signature verification step as required by the law at the time. There was even reports of voter intimidation within Arizona’s Vietnamese community by ballot collectors.

In all likelihood, the Arizona law will end up in the U.S. Supreme Court.

Whatever the legal outcome of the anti-ballot-harvesting law, Arizona’s GOP can be forgiven for having suspicions about the fraud it invites. Their memory is still fresh over Republican Senate candidate Martha McSally losing her election-night vote lead to Democrat Kyrsten Sinema after the mail-in ballots were counted over the subsequent week.

Ballot harvesting, however, has many proponents.

California Secretary of State Alex Padilla aggressively defended his state’s ballot harvesting practice to Politico after the GOP complained at how it affected many California races in the 2018 midterms: “It is bizarre that Paul Ryan cannot grasp basic voting rights protections. Our elections in California are structured so that every eligible citizen can easily register, and every registered voter can easily cast their ballot.”

“For some people, this is a question of convenience and some others are more concerned about security,” according to Wendy Underhill, the director of elections and redistricting for the National Conference of State Legislatures, who studies variations in state laws for ballot-collecting.

Large-scale ballot fraud can often be detected using various forensic techniques such as Benford’s Law, particularly when the fraud results in dramatic changes in turnout. What makes ballot harvesting problematic is not just its vulnerability to ballot fraud but its documented impact on voter turnout. If the NPVIC becomes a reality, both parties will have a strong incentive to significantly amp up their GOTV efforts.

Under a national popular vote, a voter turnout arms race will likely ensue and who knows the unintended consequences of that competition.

The Nebraska/Maine elector system should be adopted nationwide

Interest by Democrats in converting U.S. presidential elections to a popular vote is understandable, independent of Trump’s 2016 triumph. But, the NPVIC is a blunt force way of getting there and probably not going to pass enough state houses anyway.

In the meantime, before we impulsively chuck the entire EC system into the circular file in favor of a popular vote, we may want to consider other options that are less disruptive and not as exposed to unintended consequences.

The national debate largely pivots on these two objectives for U.S. presidential elections: (1) representation of the popular will, and (2) a sufficient geographic distribution of voter support to include as many sectarian interests as possible.

The most discussed alternative to the EC and direct popular vote is a method already in use in Nebraska and Maine — the congressional district method — where electors are awarded based upon popular vote totals within each of the 435 congressional districts. It is a not a direct popular vote, but it is a decent approximation. [Note: Trump still would have won in 2016 under the congressional district method.]

One virtue of the congressional district method is its compatibility with the Founding Fathers’ original intent when writing the Constitution. We don’t live in the United Peoples of America. We live in the United States of America. Spurning King Solomon’s wisdom, the Founding Fathers figuratively split the baby in half when they created a federal system where both the central government and the states share sovereignty. The EC is a 230-year-old institution borne from this compromise.

“Federalism goes beyond states’ rights and powers. Its essence is dual sovereignty — the Framers’ ingenious system of shared authority between federal and state governments with each sovereign checking the other,” writes Cato Institute Chairman Robert A. Levy of the CATO Institute. “The purpose of that check is to shield individuals from concentrations of power. Federalism is first and foremost a device to safeguard personal freedom.”

The EC is deeply flawed and threatens the legitimacy of our nation’s highest office. We cannot afford many more presidential elections, like 2016, where the EC result differs from an inherently biased but still widely reported popular vote. A crisis of legitimacy over how we elect our president will undermine the effectiveness of the Office of the President, if it hasn’t already.

At a minimum, the EC needs to be modified to the congressional district method as soon as possible. It is too late for 2020. But a bipartisan effort to adopt this method for most, if not all, states before the 2024 election is possible and should be something both parties can agree upon for once.

- K.R.K.

Send comments and suggestions to: kroeger98@yahoo.com

About the author: I am a survey and statistical consultant with over 30 -years experience measuring and analyzing public opinion (You can contact me at: kroeger98@yahoo.com)