By Kent R. Kroeger (NuQum.com, September 16, 2019)

________________________________________________________________

The following is the first of two essays about the Electoral College and the initiative to replace it with the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC). The first essays focuses on arguments by the Founding Fathers in support of the Electoral College — particularly the writings of James Madison and Alexander Hamilton in The Federalist Papers. The second essay focuses on the NPVIC and details some of its problems (and virtues) relative to the Electoral College and offers a compromise system — the congressional district method — already employed in Nebraska and Maine.

________________________________________________________________

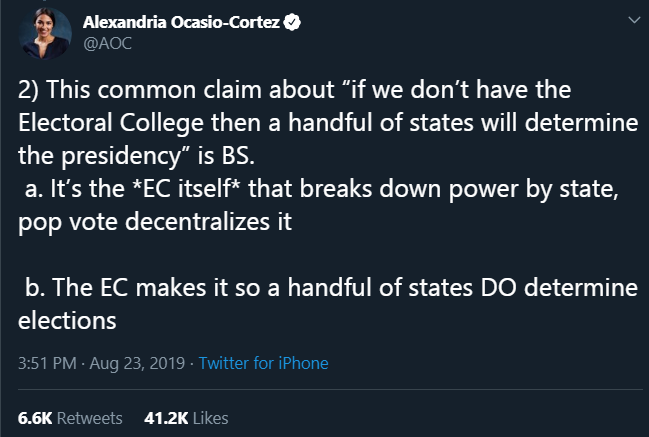

As she has done many times in her short tenure as a U.S. Representative, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) set off a low-grade political storm last month when she followed her Instagram video declaring the Electoral College a “racist injustice breakdown” (what ever that means) with these tweets:

Ocasio-Cortez’ jeremiad against the Electoral College (EC) offers the standard rationale, as in her tweet thread’s first and fifth points concerning the over-representation of voters in small-population states and the subversion of the majority’s will. Her second point, however, is quite flawed and exemplifies much of the misinformation in circulation about the EC’s inherent biases.

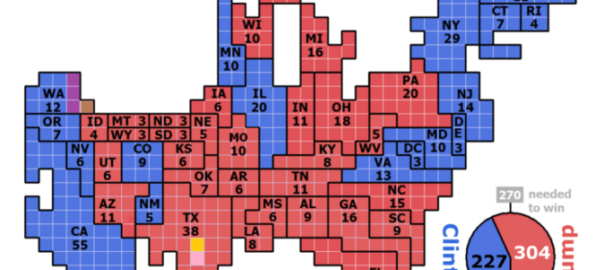

The EC does not guarantee that a “handful of states” will determine the president — though, theoretically, a candidate could win the presidency winning the 11 largest states (CA, FL, GA, IL, MI, NJ, NY, NC, OH, PA, TX). But it is the Democrats who would most likely benefit from a large state coalition since they politically dominate four of the 11 largest states (CA, IL , NJ, NY) while the Republican control only two (GA, TX).

In reality, since neither party dominates the majority of large states, the EC encourages (or, rather, demands) the geographic dispersion of voter support, not its concentration, as suggested by the freshman congresswoman from New York.

With that minor disagreement notwithstanding, like Ocasio-Cortez, I also have little affection for the EC. It is an artifact of an old political compromise made by men holding deep biases against some of the political assumptions commonly held today. The Founding Fathers, by creating the EC, commingled their aversion to direct democracy with the unrepresentative nature of the U.S. Senate, itself a compromise necessary to secure support for the creation of the United States and which, in the legislative process, gives disproportionate power to the least populated states.

“Since there now are a greater number of sparsely-populated, mostly-white, right-leaning states than there are heavily-populated, racially-diverse, left-leaning states, the Senate acts to preserve power for people and groups who would otherwise have failed to earn it,” laments GQ political writer Jay Willis. “A voter in Wyoming (population 579,000) enjoys roughly 70 times more influence in the Senate than a voter in California (population 39.5 million).”

Abolishing the U.S. Senate is a bridge too far admits Willis — which is why many critics of the U.S. Senate’s constitutionally enshrined status turn their ire towards the EC, an institution roughly half of American adults support replacing with a popular vote system.

However, preserving the Founding Fathers’ original intentions by keeping at least some form of the EC is worth, at a minimum, an earnest defense, even if we do eventually reform or abolish it.

It is unlikely the Founding Fathers would look at the 2016 election and think the popular vote would solve our problems

I generally resist ‘original intent’ arguments as to why any aspect of the U.S. Constitution needs to be preserved. The Founding Fathers never anticipated our present world, making it crucial that the Constitution and its Amendments be subject to judicious review when social evolution demands it. The EC has earned such a re-examination.

The Founders’ original intent in creating the EC is worth considering, in part, because most contemporary commentators fail to appreciate how distrustful the Founders were of direct democracy and its inability to solve what they considered the fundamental challenges of democracy: to stunt the formation of factions and stop the rise of men to the nation’s highest office possessing only “talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity.” The EC is just one manifestation of their wariness of direct democracy.

James Madison expressed in The Federalist Papers (Federalist Paper №10 — The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection) an opinion common among intellectuals at the time regarding direct (or pure) democracy:

“…a pure democracy, by which I mean a society consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the government in person, can admit of no cure for the mischiefs of faction. A common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by a majority of the whole; a communication and concert result from the form of government itself; and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party or an obnoxious individual. Hence it is that such democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths. Theoretic politicians, who have patronized this species of government, have erroneously supposed that by reducing mankind to a perfect equality in their political rights, they would, at the same time, be perfectly equalized and assimilated in their possessions, their opinions, and their passions.”

According to Madison, with direct democracy (“one person, one vote”) follows the inevitable rise of factions and a resultant political chaos, particularly within “societies consisting of a small number of citizens.” In other words, people in relatively small groups can’t govern themselves.

But what about big groups?

Madison’s prescription was to establish “a republic…a government in which the scheme of representation takes place, opens a different prospect, and promises the cure for (factions).” The interests of the people would be delegated to elected representatives — some elected directly (U.S. House members) and some elected by the state legislatures (U.S. Senate members until 1914).

But more interesting than Madison’s circumspection about direct democracy was his belief that representative democracy has a sweet spot at the national level where representatives should not represent too many people, nor too few.

Wrote Madison in Federalist Paper №10: “… however small the republic may be, the representatives must be raised to a certain number, in order to guard against the cabals of a few; and that, however large it may be, they must be limited to a certain number, in order to guard against the confusion of a multitude…By enlarging too much the number of electors, you render the representatives too little acquainted with all their local circumstances and lesser interests; as by reducing it too much, you render him unduly attached to these, and too little fit to comprehend and pursue great and national objects.”

However, in establishing the people’s chamber — the U.S. House of Representatives — the U.S. Constitution set no maximum as to how many people (free persons) a House member can represent, but there is a minimum as to how few they can represent.

Set forth in Article I (Section 2) of the U.S. Constitution: The number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every thirty thousand, but each state shall have at least one Representative.

When the U.S. House passed the Permanent Apportionment Act of 1929, it fixed the number of House members at 435 (as it stands today), regardless of national population growth. Thus, while the size of a state’s U.S. House delegation depends on its population and can grow with that state’s population growth, there is a theoretical maximum of 386 House members for any given state [Imagine a world where everyone lives in California, except for one person living in each of the other 49 states].

Today, the average U.S. House member represents 750,000 people (adults and children). At the founding of the American republic, that number was about 57,000 people. By their actions, the Founders and subsequent generations of American political leaders have been more concerned about elected representatives representing too few people than too many.

That would seem to be an argument for the popular vote over the EC; after all, the President represents the common interests of 327 million Americans. Not a problem, according to the Founders, if their regard for the U.S. House is any indication.

But that is not how the Founders viewed the election of the President. Not even close.

Enter Alexander Hamilton — a skeptic about the wisdom of the masses.

In Federalist Paper №68 (The Mode of Electing the President), Hamilton explicitly rejected the idea that the selection of the President could be left to the earthly passions of the people. To the contrary, Hamilton felt the decision must be left to an exemplary set of individuals, approved by the people, but not beholden to them.

Wrote Hamilton: “It was desirable that the sense of the people should operate in the choice of the person to whom so important a trust was to be confided. This end will be answered by committing the right of making it, not to any preestablished body, but to men chosen by the people for the special purpose, and at the particular conjuncture…It was equally desirable, that the immediate election should be made by men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station (emphasis mine), and acting under circumstances favorable to deliberation, and to a judicious combination of all the reasons and inducements which were proper to govern their choice. A small number of persons, selected by their fellow-citizens from the general mass, will be most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to such complicated investigations.”

Hamilton didn’t believe the people, through a popular vote, could make such an important choice as President. In 1789, he was hardly alone in the opinion that a direct election of the President would make the office vulnerable to manipulation and potentially bound to sectarian interests.

“The process of election affords a moral certainty, that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications,” wrote Hamilton of the EC’s virtues. “Talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity, may alone suffice to elevate a man to the first honors in a single State; but it will require other talents, and a different kind of merit, to establish him in the esteem and confidence of the whole Union, or of so considerable a portion of it as would be necessary to make him a successful candidate for the distinguished office of President of the United States.”

The EC was explicitly designed to prevent someone like Donald Trump from becoming president. Were Hamilton and Madison able to join us in the present, I am certain they would look at the election of President Trump, not as a justification the popular vote, but as evidence that something else is wrong in the political system.

The Founders never intended the Electoral College to give rural America disproportionate power in the selection of the President.

Based on their writings and the actual content of Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 in the Constitution, the Founders’ central intention regarding the EC was straightforward: Its outcome — the election of a President — must be viewed as legitimate by the people.

Hamilton and Madison did not view the direct election of the President as a requisite condition for such legitimacy. Why would they? Popular sentiment in 1789 easily could have supported the ascension by decree of General George Washington as a life-time monarch.

There is also no evidence that either Hamilton or Madison (or any other participant in the Constitutional Convention of 1787) anticipated the EC results and a popular vote tally could be compared within an election. The debate within the old Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia was over what type of system to use, not running two systems simultaneously and hope both always agree as to the outcome.

Their final decision, Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution, opted for letting the states choose their electors — by a means of their own choosing — and allocating each state’s number of electors based on their numerical representation in the Congress:

Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector.

By using the U.S. House in the elector allocation formula, the Founders were attendant to the importance of population representativeness (despite their willingness to count almost 18 percent of the population as only three-fifths of a person). What they did not do is create a system where it would be easy for a cabal of small states, representing a minority of Americans, to wrest the presidency from the large-population states.

In the second presidential election (1792), the first presidential election with the participation by all states, 68 electoral votes were necessary to win the presidency (out of 132). If the smaller (mostly rural) states had joined in coalition, they nevertheless would have needed New York or North Carolina’s 12 electoral votes to win the presidency (see Figure 1). That can hardly be called a rural, small-state bias. In contrast, Virginia, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, North Carolina and New York alone — representing 46 percent of the total U.S. population at the time — could, as a bloc, determine the outcome of a presidential election.

Figure 1: The U.S. Population and Electoral College by State in 1792

If Hamilton or Madison could engage Ocasio-Cortez regarding the EC, they might address her concerns — particularly her third third point (“the Electoral College provides ‘fairness’ to rural Americans” at the presumed detriment to other groups) — with this response: There was never an intention by the Founders to give rural America disproportionate power in the selection of the President. Quite the opposite, the Electoral College was designed by elites for elites to elect other elites. Their objectives were focused on placing an additional layer of protection between the presidency and the common, easily manipulated tastes of the general masses.

From the Founders’ mindset, the election of Donald Trump was a failure of the nomination process, not the Electoral College.

- K.R.K.

Send comments and constitutional amendment proposals to: kroeger98@yahoo.com