By Kent R. Kroeger (NuQum.com, August 26, 2019)

In the late summer of 1994, I walked into a small, two-story Fairfax, Virginia office in the middle of a nondescript commercial complex of converted town homes, itself residing on the edge of a middle-class residential neighborhood.

The sign in the front window — Republican Party of Virginia — was faded from sunlight exposure and severely bent on the corners. After a few unanswered doorbell rings, I just walked in through its half-opened front door. Not a soul in sight.

“Hello!” I sheepishly bellowed. No answer. I walked halfway up some musty-smelling stairs, softly issued a last ‘Hello!’ and walked back down the stairs, picking up a couple of brochures at the receptionist’s desk as I walked out.

“Can I help you?” I heard as I opened my car door to leave. A large man approached me with a striking resemblance to Sebastian Cabot (a reference only someone over 50 can visualize).

“Yes, sir,” I replied. “I’d like to volunteer for the upcoming election if you need help.”

So began my 20-year-plus defection from the Democrats to the Republicans.

Only six years earlier, I volunteered for Jesse Jackson’s second presidential campaign and, four years before that, worked as a paid staffer for then-Iowa congressman Tom Harkin’s first U.S. Senate campaign. In that same 1984 election, as a Black Hawk County Democratic delegate for Jesse Jackson, I saw first-hand how the proportion of county delegates a candidate has does not necessarily translate into the same proportion of state convention delegates.

And there I was, in 1994, on a steamy Virginia weekday morning, offering my time and effort to help people like Oliver North — who was running for the U.S. Senate against Democratic incumbent Chuck Robb — get elected.

For the next 20 years, I attended Republican precinct meetings, helped organize neighborhood fundraisers, and worked the phones for the party’s get-out-the-vote efforts. When I left the Republican Party in 2016 to work on my brother’s campaign to challenge incumbent Republican Rod Blum in Iowa’s 1st Congressional District, I felt some ambivalence.

Though never an insider for either party, as a part-time activist for over 35 years, I have developed a strong sense about each party’s organizational and cultural differences. In most cases, these dissimilarities have remained constant over variations in time and geography (Iowa, Virginia, New Jersey). These observations are not, however, necessarily a reflection of the parties’ rank-and-file supporters. And this is not a thesis on the policy differences between the two parties. The following is merely the palpable imprints the two parties left on me.

And as I now reflect on these impressions, I have come to believe some of these differences may explain why, since Watergate’s aftermath, the Republicans have won more national and state elections across this country than have the Democrats, despite the fact that public opinion across many issues has become more ‘liberal’ since 1978.

That the Republicans continue to win elections on a consistent basis cannot be explained by blessing or luck. It is more likely because the Republicans have created a leadership and activist culture organized for just one purpose: winning elections. Where the Democrats have created the world’s most sophisticated fundraising and vote harvesting apparatus in American history, the Republicans have created the most successful political party.

As to how this could happen, I turn to the three specific organizational and cultural differences I’ve observed across the two parties. This first relies a bit too much on psychoanalysis, perhaps, but I believe is the most consistent difference between the two parties since 1978.

(1) Republicans have an enduring sense of being the ‘minority’

Calling Mitt Romney’s 2012 defeat to Barack Obama one of the most painful political losses in his lifetime, conservative radio host Rush Limbaugh found clarity in a moment of despair as he told his radio audience the day after Obama’s re-election:“I went to bed last night thinking we are outnumbered. I went to bed last night thinking we’ve lost the country. I don’t know how else you look at this.”

Fox News’ inelegant host Bill O’Reilly was more direct: “The white establishment is now the minority.”

Republican feelings of being outnumbered did not start in 2012, however. Or in 2008 for that matter. In fact, it can be traced as far back as Richard Nixon’s first presidential term as he reacted to the growing anti-Vietnam protest movement. “And so tonight — to you, the great silent majority of my fellow Americans — I ask for your support,” Nixon intoned in a televised address to the nation.

But if Nixon was anything, he was a realist — laced a pinch of dark paranoia. Having won his first presidential term by a whisker’s margin, he knew any majority he might rely on politically could never be taken for granted.

Nixon’s frequent lament about his mistreatment by other political elites would contribute to his eventual downfall in the Watergate conspiracy. More broadly, many of Nixon’s personal weaknesses were imprinted onto the psyches of Republican Party’s faithful. The psychological trauma dealt to the Republican Party from the double whammy of Watergate and the inconclusive end to the Vietnam War cannot be over-estimated. Despite a relatively close presidential election in 1976, the Republican Party’s status in Congress and across the state legislatures was in descent.

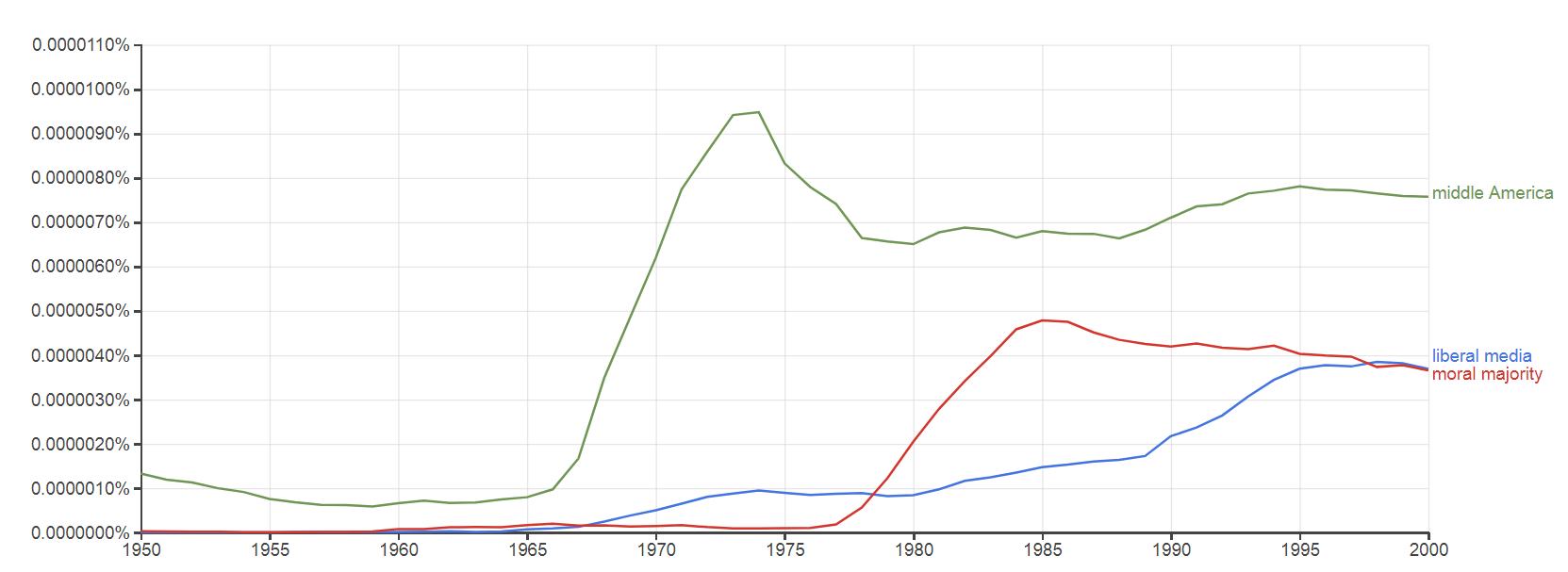

Around this time, we see the rise of terms such as ‘middle America,’ ‘liberal media,’ and ‘moral majority’ — terms still heard frequently in Republican circles (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Use of terms “middle America” (green line), “liberal media” (blue line) and “moral majority” (red line) in literature since 1950.

Source: Google Ngrams

Source: Google Ngrams

The Republicans I knew in Virginia had an “us against the D.C. political establishment” mentality. Everything, I mean everything, was working against them. To this day, my conversations with Republicans often include references to the ‘liberal media’ and ‘coastal elites.’ The news media is against them (even Fox News, according to some particularly strong Trump loyalists). Washington ‘elites’ are against them. Hollywood is against them (try to name more than one scripted TV show today that openly espouses conservative principles). Social media is against them. The public school system is against them. Academics are against them.

These laments emerged in force in the mid-1970s. The term ‘Moral Majority’ was minted by conservative religious activist Paul Weyrich from a perspective of political vulnerability, not strength. It was a defensive mobilization strategy built on a deep insecurity, heightened to toxic levels by Watergate. “We are the moral majority!” was a Republican acknowledgement of their political minority status and the electoral necessity of a coalition with like-minded Democrats and independents. In the 1980 election, many of those like-minded voters would be called ‘Reagan Democrats.’

The Republican affection for the economic aristocracy also brings with it an attendant understanding that this socioeconomic bias puts them in a definitive minority status within the electorate. Without election activities engineered to attract weak partisans and suppress enthusiasm among Democratic voters generally, the Republicans are at a serious disadvantage to the Democrats.

And, in practice, this is has been the electoral strategy of the Republican Party since Watergate. Whereas I frequently heard within the Iowa Democratic Party leadership in the 2014 and 2016 elections that all the Democrats needed to do was “get out their voters,” I don’t recall ever hearing Virginia Republican leaders uttering an equivalent sentiment. Virginia Republicans in the 1990s had endured a century of Democratic Party domination of Virginia politics. For them to think they could just turnout ‘their voters’ (as if voters are owned) would have sounded suicidal.

More importantly, the Republican’s basic approach towards the electorate, motivated by this sense of minority status, makes them a far more effective competitor on election day. Where the Democrats believe the majority of Americans already love them, the Republicans entertain no such assumption.

Any attempt to explain why Republican candidates have kept winning elections since Watergate must therefore include, if not be dominated by, an understanding of their deep sense of their own minority status.

(2) Republicans are more tolerant than Democrats of opinion diversity within its ranks

In my experience with Virginia Republicans and Iowa Democrats, I witnessed two different management styles by the party leaders that impacted how opinion differences were handled within the organizations.

In 1994, when I joined the Republican Party of Virginia (RPV), there was open warfare between upstate (D.C.-area) conservatives, who tended to be more liberal on social issues, and the downstate conservatives, who were much more conservative. The religious right had just won the RPV chair position (Patrick McSweeney) but the battle was far from being won. What left an impression with me was how the Virginia Republicans more frequently engaged in bottom-up conversations. The Republican activists and volunteers I met, many of whom were already successful professionals outside of the party, were not overly deferential towards the party’s staff and leaders. In fact, they were often dismissive of the ‘political hacks’ running the state party. The organization less hierarchical and, frankly, more democratic.

The Iowa Democratic Party (IDP) was the opposite. The party leaders were either career activists that had risen up the ranks or were from academia; whereas, the activists and volunteers were typically students or young professionals early in their careers. This made the IDP more hierarchical and affected internal dialogues which were almost always top-down and less democratic.

Strict hierarchies tend to suppress diversity of opinion within an organization; flat organizations much less so.

Still, I encounter resistance anytime I suggest to a Democrat that the Republican Party is more tolerant of opinion diversity. ‘No f**king way,’ is a common response.

But, in fact, way.

Such resistance is rooted in a common belief that intellectual nimbleness is associated with higher levels of education. In reality, this is not necessarily true — at least not when it comes to politics. According to the analytics firm, PredictWise, the most politically intolerant Americans “tend to be whiter, more highly educated, older, more urban, and more partisan” and lean liberal, particularly on social issues.

This finding augments research by University of Pennsylvania professor Diana Mutz, who concluded in her book Hearing the Other Side that white, highly educated people — who skew Democrat and liberal — tend not to talk with people who disagree with them — which makes the probability higher that they will stereotype those with opposing views.

Self-selection bias impacts how we organize our lives, including who we talk to on a regular basis. The more educated and wealthier we become, the more we can control that dynamic and homogenize our surroundings.

But I posit another factor behind higher levels of opinion tolerance among Republicans. Most of the Virginia Republican leaders, activists and volunteers I met were already (or had been) successful business people from the private sector. They often had MBAs or business law backgrounds and were almost always private sector oriented.

Why does that matter?

Most businesses, large or small, try to avoid politics when making contact with current or potential customers. The big companies may hire powerful Beltway lobbyists to do the dirty partisan work, but at the point-of-sale, partisan politics does more harm than good. Republican party leaders and activists understand that better than their Democratic counterparts because they are more likely to have dealt with that issue in their professional lives.

In contrast, many Democratic Party leaders and activists have only worked in academia or in the non-profit, public advocacy sector. Planned Parenthood isn’t in the business of compromising its policy message in order to appeal to a broader audience. Greenpeace activists aren’t looking for common ground with Exxon-Mobil so they can work together more effectively. The Democrat DNA is fundamentally different and inherently resistant to compromise and opinion diversity.

Again, why does this matter? Because the electoral arena has more in common with consumer brand market competition than it does to an academic symposium on immigration policy or a non-profit funded public awareness campaign. Brands are forced to adjust to market realities in ways few advocacy groups ever encounter. “A wise man adapts himself to circumstances, as water shapes itself to the vessel that contains it,” says an old Chinese proverb. A more contemporary quote comes from business author Alan Deutschman who popularized the business catchphrase, “Change or die.”

The Republican Party is powered by a different culture and mindset than the Democratic Party. It makes the GOP more flexible on issues when it matters most — at election time. Republicans are betting at adapting to changing market conditions.

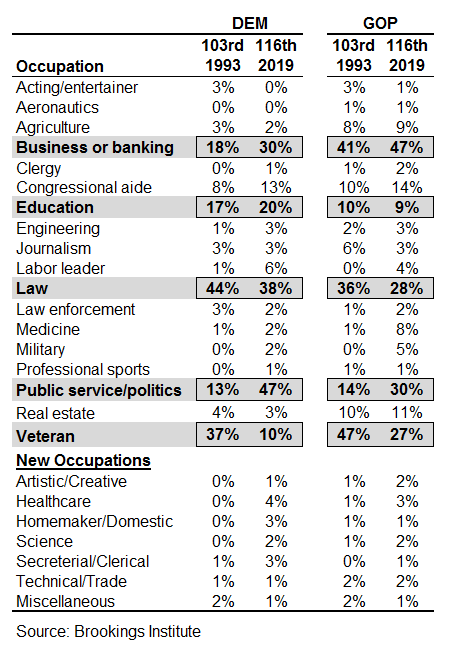

This cultural difference manifests itself when looking at the prior occupations of U.S. House members in the 103rd Congress and the current 116th Congress (see Figure 2). In the 103rd Congress, 41 percent of GOP members had a business background and that would rise to 47 percent in the 116th Congress. Only 18 percent of Democrat House members had a business background in the 103rd Congress, though it has risen to 30 percent in the current Congress. The other stark difference is in those House members with a public service or political activism background. As of today, 47 percent of Democrat House members have a public service/political background, compared to only 30 percent of GOP members.

Figure 2: Occupations of U.S. House members in the 103rd Congress and the 116th Congress (House members can have multiple prior occupations)

The rise of Donald Trump is a living testament to the ability of the Republican Party and its rank-and-file supporters to embrace change and diversity. How can an evangelical Christian who abhors adultery embrace Trump? Apparently, its pretty easy when you believe you need to compromise on a candidate’s qualities in order to win elections. Does that sound like a quality commonly found among Democrats? I would say not, even if Joe Biden is still leading in the 2020 Democratic nomination race.

(3) Republicans hold themselves accountable for failure

Business people love quantitative performance metrics. They measure like their career depends on it, because if often does. And they always have that one, bottom line metric looming over them: profits.

The Republican National Committee (RNC) has a similar orientation. The party doesn’t value moral victories. The RNC cares about one metric: You either win or lose. It’s the Ricky Bobby theory of electoral politics: If you ain’t first, you’re last.

That’s why Republicans have no problem turning on themselves when their party loses an election. I wouldn’t call it introspection on their part. It’s more like, “We just lost, I need to fire somebody in this office.”

When the Republicans lost to Barack Obama in 2008, Senator John Cornyn, chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, turned the spotlight on his entire party. “While some will want to blame one wing of the party over the other, the reality is candidates from all corners of our GOP lost tonight. Clearly we have work to do in the weeks and months ahead.”

There was little vote-shaming (i.e., blaming voters for how they voted) by Republican leaders after 2008 (though there was some of that after the 2012 election when some in the GOP pundit class blamed voters for wanting ‘more stuff.’).

After the 2012 election, the RNC commissioned an internal study to explain the election results and how the party needed to adjust going forward. The Atlantic’s Garance Franke-Ruta described the 2012 postmortem report as “an astonishingly frank document that calls for major changes in how the party addresses minorities, women, and its own campaign processes.”

No such study has ever been released by the Democratic National Committee (DNC) following their 2016 election debacle. Instead, groups outside the DNC have picked up the slack. One group, DemocraticAutopsy.org, led by Karen Bernal, a three-term Chair of the California Democratic Party’s Progressive Caucus, Pia Gallegos, Chair of the Adelante Progressive Caucus of the Democratic Party of New Mexico, Sam McCann, a writer, and Norman Solomon, co-founder of RootsAction.org, produced their own report.

Unfortunately, such “independent” reports are more ideological treatises than true objective analyses — which is what the Democratic Party desperately needed after 2016.

Instead of critiquing their party’s policy and voter outreach strategies, as the Republicans did after 2012, the DNC and most Democratic leaders have blamed Russia for their 2016 loss to Trump.

Like a starving dog pack, the Republicans act collectively after electoral defeats; while, in contrast, the Democrats scurry about doing their own individual thing hoping that somehow it will all come together when the next election rolls around.

Republicans more collectivist? Democrats more individualistic? Isn’t that backwards?

Not at all.

There are many organizational and cultural characteristics distinguishing the Republicans from the Democrats. The three differences I’ve highlighted here may seem counter intuitive, which is why I believe the Democrats must acknowledge them if they are ever going to sustain any electoral success over multiple, contiguous elections.

As of today, it is the Democratic Party that shuns introspection and instead leans on undemocratic processes to push its agenda and pre-approved candidates through to its rank-and-file supporters. Underwriting this culture is the Party’s widely held belief that Democrats are the manifest majority in the U.S. and will become even more so as the country’s demographics change going forward. ‘All we have to do is turn out our voters,’ they tell themselves.

American’s electoral history is a graveyard for such hubris.

If the Democratic Party’s organizational culture doesn’t change, I predict more unexpected defeats in its future.

K.R.K.

Please send comments to: kroeger98@yahoo.com