By Kent R. Kroeger (January 21, 2021)

Political scientist Harold Lasswell (1902–1978) said politics is about ‘who gets what, when and how.’

He wrote it in 1936, but his words are more relevant than ever.

In the U.S., his definition is actualized in Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution:

The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defense and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States;

To borrow Money on the credit of the United States;

To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian Tribes;

To establish an uniform Rule of Naturalization, and uniform Laws on the subject of Bankruptcies throughout the United States;

To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures.

In short, the U.S. Congress has the authority to create money — which they’ve done in ex cathedra abundance in the post-World War II era.

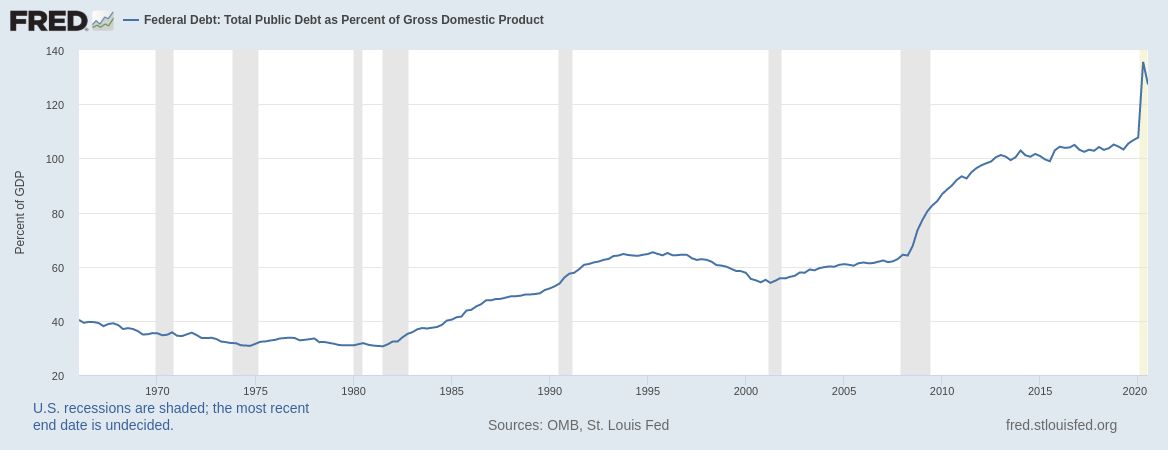

According to the U.S. Federal Reserve, the U.S. total public debt is 127 percent of gross domestic product (or roughly $27 trillion) — a level unseen in U.S. history (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Total U.S. public debt as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP)

And who owns most of the U.S. debt? Not China. Not Germany. Not Japan. Not the U.K. It is Americans who own roughly 70 percent of the U.S. federal debt.

Its like owing money to your family — and if you’ve ever had that weight hanging over your head, you might prefer owing the money to the Chinese.

When it comes to dishing out goodies, the U.S. Congress makes Santa Claus look like a hack.

But, unlike Saint Nick, Congress doesn’t print and give money to just anyone who’s been good— Congress plays favorites. About 70 percent goes to mandatory spending, composed of interest payments on the debt (10%), Social Security (23%), Medicare/Medicaid (23%), and other social programs (14%). As for the other 30 percent of government spending, called discretionary spending, 51 percent goes to the Department of Defense.

That leaves about three trillion dollars annually to allocate for the remaining discretionary expenditures. To that end, the Congress could just hand each of us (including children) $9,000, but that is crazy talk. Instead, we have federal spending targeted towards education, training, transportation, veteran benefits, health, income security, and the basic maintenance of government.

There was a time when three trillion dollars was a lot of money — and maybe it still is — but it is amazing how quickly that amount of money can be spent with the drop of a House gavel and a presidential signature.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, passed by the U.S. Congress and signed into law by President Donald Trump on March 27, 2020, costed out at $2.2 trillion, with about $560 billion going to individual Americans and the remainder to businesses and state or local governments.

That is a lot of money…all of it debt-financed. And the largest share of it went directly to the bank accounts of corporate America.

And what do traditional economists tell us about the potential impact of this new (and old) federal debt? Their collective warning goes something like this:

U.S. deficits are partially financed through the sale of government securities (such as T-bonds) to individuals, businesses and other governments. The practical impact is that this money is drawn from financial reserves that could have been used for business investment, thereby reducing the potential capital stock in the economy.

Furthermore, due to their reputation as safe investments, the sale of government securities can impact interest rates when they force other types of financial assets to pay interest rates high enough to attract investors away from government securities.

Finally, the Federal Reserve can inject money into the economy either by directly printing money or through central bank purchases of government bonds, such as the quantitative easing (QE) policies implemented in response to the 2008 worldwide financial crisis. The economic danger in these cases, according to economists, is inflation (i.e., too much money chasing too few goods).

How does reality match with economic theory?

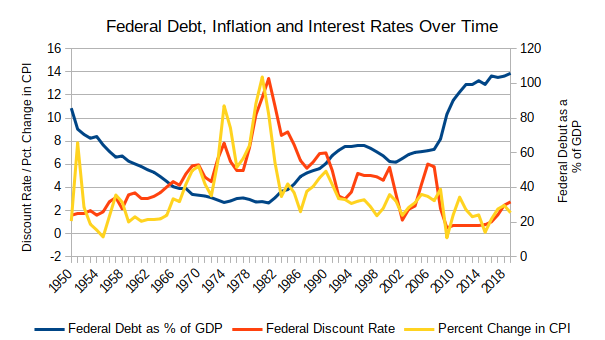

I am not an economist and don’t pretend to have mastered all of the quantitative literature surrounding the relationship between federal debt, inflation and interest rates, but here is what the raw data tells me: If there is a relationship, it is far from obvious (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: The Relationship between Federal Debt, Inflation and Interest Rates

Despite a growing federal debt, which has gone from just 35 percent of GDP in the mid-1970s to over 100 percent of GDP following the 2008 worldwide financial crisis (blue line), interest rates and annual inflation rates have fallen over that same period. Unless there is a 30-year lag, there is no clear long-term relationship between federal deficits and interest rates or inflation. If anything, the post-World War II relationship has been negative.

Given mainstream economic theory, how is that possible?

The possible explanations are varied and complex, but among the reasons for continued low inflation and interest rates, despite large and ongoing federal deficits, is an abundant labor supply, premature monetary tightening by the Federal Reserve (keeping the U.S. below full employment), globalization, and technological (productivity) advances.

Nonetheless, the longer interest rates and inflation stay subdued amidst a fast growing federal debt, it becomes increasingly likely heterodox macroeconomic theories — such as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) — will grow in popularity among economists. At some point, consensus economic theory must catch up to the facts on the ground.

What is MMT?

Investopedia’s Deborah D’Souza offers a concise explanation:

Modern Monetary Theory says monetarily sovereign countries like the U.S., U.K., Japan, and Canada, which spend, tax, and borrow in a fiat currency they fully control, are not operationally constrained by revenues when it comes to federal government spending.

Put simply, such governments do not rely on taxes or borrowing for spending since they can print as much as they need and are the monopoly issuers of the currency. Since their budgets aren’t like a regular household’s, their policies should not be shaped by fears of rising national debt.

MMT challenges conventional beliefs about the way the government interacts with the economy, the nature of money, the use of taxes, and the significance of budget deficits. These beliefs, MMT advocates say, are a hangover from the gold standard era and are no longer accurate, useful, or necessary.

More importantly, these old Keynesian arguments — empirically tenuous, in my opinion — needlessly restrict the range of policy ideas considered to address national problems such as universal access to health care, growing student debt and climate change. [Thank God we didn’t get overly worried about the federal debt when we were fighting the Axis in World War II!]

Progressive New York congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has consistently shown an understanding of MMT’s key tenets. When asked by CNN’s Chris Cuomo how she would pay for the social programs she wants to pass, her answer was simple (and I paraphrase): The federal government can pay for Medicare-for-All, student debt forgiveness, and the Green New Deal the same way it pays for a nearly trillion dollar annual defense budget…just print the money.

In fact, that is essentially what this country has done since President Lyndon Johnson decided to prosecute a war in Southeast Asia at the same time he launched the largest set of new social programs since the New Deal.

Such assertions, however, generate scorn from status quo-anchored political and media elites, who are now telling the incoming Biden administration that the money isn’t there to offer Americans the $2,000 coronavirus relief checks promised by Joe Biden as recently as January 14th. [I’ll bet the farm I don’t own that these $2,000 relief checks will never happen.]

Cue the journalistic beacon of the economic status quo — The Wall Street Journal — which plastered this headline above the front page fold in its January 19th edition: Janet Yellen’s Debt Burden: $21.6 Trillion and Growing

WSJ writers Kate Davidson and Jon Hilsenrath correctly point out that the incoming U.S. Treasury secretary, Yellen, was the Chairwoman of the Clinton administration’s White House Council of Economic Advisers and among its most prominent budget deficit hawks, and offer this warning: “The Biden administration will now contend with progressives who want even more spending, and conservatives who say the government is tempting fate by adding to its swollen balance sheet.”

This misrepresentation of the federal debt’s true nature is precisely what MMT advocates are trying to fight, who note that when Congress spends money, the U.S. Treasury creates a debit from its operating account (through the Federal Reserve) and deposits this Congress-sanctioned new money into private bank accounts and the commercial banking sector. In other words, the federal debt boosts private savings — which, according to MMT advocates, is a good thing when the “debt” addresses any slack (i.e., unused economic resources) in the economy.

Regardless of MMT’s validity, this heterodox theory reminds us of how poorly mainstream economic thinking describes the relationship between federal spending and the economy. From what I’ve seen after 40 years of watching politicians warn about the impending ‘economic meltdown’ caused by our growing national debt, consensus economic theory seems more a tool for politicians to scold each other (and their constituents) about the importance of the government paying its bills than it is a genuine way to understand how the U.S. economy works.

Yet, I think everyone can agree on this: Money doesn’t grow on trees, it grows on Capitol Hill. And as the U.S. total public debt has grown, so have the U.S. economy and wealth inequality — which are intricately interconnected through, as Lasswell described 85 years ago, a Congress (and president) who decide ‘who gets what, when and how.’

- K.R.K.

Send comments and your economic theories to: nuqum@protonmail.com