By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, June 25, 2021)

In his classic 1984 Duke Law Journal essay, The Marketplace of Ideas: A Legitimizing Myth, Law Professor Stanley Ingber described the news and information landscape within the U.S. in ways easily applied to today:

“In our complex society, affected by both sophisticated communication technology and unequal allocations of resources and skills, the marketplace’s inevitable bias supports entrenched power structures or ideologies. Most reform proposals do little to help the marketplace reach its theoretical potential. Instead, such suggestions perpetuate the marketplace’s status quo bias or result in unacceptable levels of governmental interference and regulation.” (p. 85–86)

But Ingber’s view of our information ecosystem doesn’t require a conspiracy among economic and political elites to explain its biased effects:

“…the New Left presumed that this effect resulted from a conspiracy of established groups. Their view of the system as a construct of devious, manipulating elites seems overly simplistic. The elites need not consciously create and impose a system in order to benefit from it. The bias or skew toward established groups and dominant value perspectives instead may be unavoidable in a high-technology society in which resources and skills are distributed unequally.” (p. 85)

To Ingber, inequities in what facts, ideas and opinions most prominently make it into the information bloodstream stem from systemic inequities, not the coordinated actions of a small cadre of elites — which is why he dismisses popular freedom of speech reforms, such as The Fairness Doctrine and federal election campaign laws, that he said “easily could decay into formal systems of governmental censorship or popular indoctrination.”

“If we intend to design a social and political system open to the development of diverse perspectives and values, we must first understand how an idea initially outside the community agenda of alternatives becomes accepted within it.” (p. 86)

While Ingber rejects leftist assumptions that the system is the product of “devious, manipulating elites,” he may have been equally naive in believing powerful interests don’t have a demonstrable, independent impact on existing imbalances on what information gets promulgated within the mainstream news media. Nonetheless, Ingber’s analysis from 40 years ago remains brutally relevant to today.

Ingber argued some legitimate perspectives, outside mainstream thought, are denied access to a sizable audience because of structural barriers within the system.

In rare instances, such as when ecological realities profoundly change — like in the Great Depression or the Vietnam War — do novel perspectives become integrated into the mainstream discourse, according to Ingber. “There is little doubt that a change in the ecological setting necessarily creates new interests and needs which in turn alter perspectives,” he wrote.

So we must wait until the next great economic recession or counterproductive U.S. military intervention to see substantive changes in status quo thinking? Ingber offers another path:

“In addition to ecological change, new perspectives and values may be nurtured in a society that encourages, or at least permits, the development of new interests and experiences. Consequently, the status quo bias of the marketplace can probably be neutralized only by protecting a greater liberty of action — allowing people to choose among lifestyles offering differing roles and relationships — rather than merely supporting the freedom of speech.”

Homogeneous sourcing: A case study using a New York Times story on ISIS in Africa.

At the heart of the Ingber argument is that a diversity of perspectives is critical to minimizing the ‘status quo bias’ of the marketplace of ideas: An informed, free-thinking society, empowered by experiential diversity, is capable of navigating contradictory ideas (including falsehoods) when given the necessary information needed to weigh them against one another.

Ingber’s 1984 essay came to my mind recently as I waded through hundreds of news articles about the alleged growing strength of jihadists on the African continent — articles like the following:

ISIS attacks surge in Africa even as Trump boasts of a ‘100-percent’ defeated caliphate (Washington Post, October 18, 2020)

Is Africa overtaking the Middle East as the new jihadist battleground? (BBC, December 3, 2020)

In bid to boost its profile, ISIS turns to Africa’s militants (New York Times, April 7, 2021)

With few exceptions, these articles and many others like them rely heavily on official government sources and U.S./European-centric think tank analysts, who, by training and financial support, back a common thesis: Islamic extremists are turning to Africa to continue and expand their war against Western institutions and influence.

Keep in mind, we are talking about a continent with over 1.2 billion people (of whom 44 percent are Muslim), and more racial/ethnic/genetic diversity than any other continent on the planet. Almost any hypothesis regarding Islam can find anecdotal support somewhere within its vast geography.

On one hand, Islamic jihadists are on the rise (Ansar Dine in Mali) ; and, on the other, Islam and democracy are not antithetical (Tunisia).

Africa and Islam are too complex to summarize in pithy headlines.

And, yet, that is exactly what our most prestigious news organizations do every day, and they do so while generally depending on a relatively narrow range of sources and perspectives.

As anecdotal evidence, we have the April 7th New York Times article, by Christina Goldbaum and Eric Schmitt, which included these sources:

(1) The Soufan Group — a New York-based security consulting firm founded by an ex-FBI interrogator— Ali Soufan — and highly regarded within the U.S. national security establishment,

(2) Africa Center for Strategic Studies — a U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) research institute,

(3) Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS — a U.S. State Department-organized coalition of 80 nations opposed to ISIS,

(4) ExTrac — a private, data-driven intelligence service (based in the U.S.) which combines “real-time attack and communications data with artificial intelligence (AI) to provide actionable insights for counterterrorism and Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) policymakers and practitioners,”

(5) The International Crisis Group — a non-profit, non-governmental organization used by policymakers and academics “working to prevent wars and shape policies that will build a more peaceful world,” though described by journalist Tom Hazeldine as a group that “consistently championed NATO’s wars to fulsome transatlantic praise,”

(6) Mozambican Research Institute (Observatory of Rural Areas) — a Mozambican non-governmental organization that aims to contribute to the sustainable development of Mozambique’s rural regions,

(7) “Experts and officials in the U.S. and Europe,”

(8) “American and United Nations counterterrorism officials.”

These aren’t necessarily disreputable or dishonest sources for knowledge about Islamic State (IS)-related militant activities in Africa, but they are demonstrably linked to the U.S.-European security and foreign policy establishment — with the exception of the Mozambican Research Institute, which was one of the few sources in the Times article saying Islamic State jihadists are not well-liked among rural Mozambicans.

Most of the Times’ sources represent a bounded range of viewpoints on the strength of Islamic militants in Mozambique and the continent overall. To the Times’ credit, alternative viewpoints were elicited in their story — the problem is that it took until the 30th paragraph in a 36-paragraph story to hear them:

“People in Cabo Delgado (Mozambique) have come to realize this group is not a solution, it’s destroying the local economy and it’s become very, very violent with the population,” said João Feijó, a researcher at the Mozambican Observatory of Rural Areas. “Nowadays the group is pretty isolated.”

That represents status quo journalism in a nutshell: Rely almost entirely on establishment sources and declare the story balanced because an alternative opinion was cited somewhere near the end of the story.

It is not a conspiracy — it is merely the result of journalists taking the path of least resistance by emphasizing expediency and ‘what is publishable’ over healthy intellectual curiosity.

What should international affairs journalists be doing instead? My answer would be something told to me in my first journalism class by the late Hanno Hardt, Professor Emeritus in the University of Iowa’s School of Journalism and Mass Communication:

Seek as many points of view as necessary to tell the whole story.

The Times story on the Islamic State in Mozambique or the other ‘rise of IS in Africa’ articles, all offer one dominant perspective — that of the U.S.-European defense and security community.

However, scratch the surface of this narrative — Islamic extremism is rising in Africa and the U.S. and Europe must somehow intervene — and the story becomes more complicated and less open to easy solutions.

We can start by looking at overall trends…

A little data sheds a lot of light on African violence

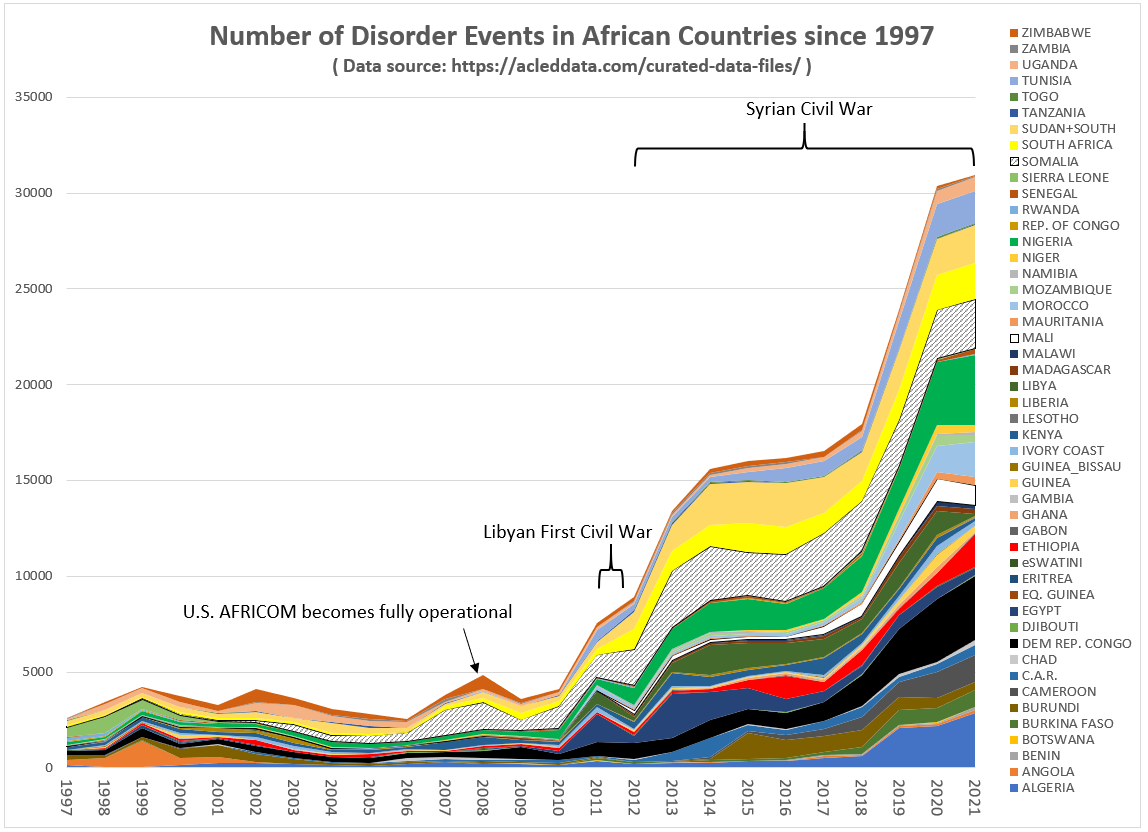

Figure 1 shows the number of disorder events occurring in Africa since 1997, according to The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), a widely used real-time data and analysis source on political violence and protest around the world.

The topline finding is that violence is on the rise in Africa and it is happening in more than Muslim-majority or near-majority countries — it is happening throughout the continent.

Figure 1: Disorder events in African countries since 1997

Not as easily discernible in the above time-series graph, however, is what may be causing this surge in violence.

Here are some initial thoughts…

There is academic research and strong anecdotal evidence that the aftermath of the Libyan and Syrian civil wars played a significant role in the timing and spread of this violence in Africa.

One of the first and largest year-to-year increases in African violence (i.e., disorder events) occurred from 2010 to 2011, which coincides with a series of key events in north Africa and the Middle East: (1)The Arab Spring, beginning with protests in Tunisia on December 18, 2010 in Sidi Bouzid, (2) the practical end of the U.S. occupation of Iraq, (3) the start and end of the First Libyan Civil War, and (4) the start of the (still on-going) Syrian Civil War.

The significant year-to-year rise in African violence continues until it tapers off in 2015 and remains relatively constant through 2017, when it starts to dramatically increase again in 2018 — the year after Bashar al-Assad’s government forces in Syria, with the help of Russia and Iran, finally gained the upper hand against the Islamic State (ISIS) and other jihadist forces, leading to a reduction in violence across most of the country, and prompting some jihadists to leave Syria to go home or join other conflicts (e.g., Afghanistan).

Through the first five months of 2021, five African countries — Nigeria, Dem. Rep. of Congo (DRC), Algeria, Somalia, and South Africa — account for nearly half (46%) of all disruptive events on the continent, according to ACLED, of which two are predominately Christian countries (DRC and South Africa).

It does not minimize the present threat of Islamic extremists in Africa (which is real) to acknowledge that a significant amount of the current violence is not related to Islam. And where Islamic extremism is the issue, it is fair to recognize that Western powers played a crucial role in events leading up to Islamic extremism’s rise in Africa.

The Arab Spring in Africa’s Maghreb and the First Libyan Civil War

A common conclusion among Western analysts about rising African violence is that it is partially a byproduct of ISIS’ defeat in Syria, 2011’s Arab Spring, and the return home of foreign fighters from Libya’s First Civil War.

Let us start with the first point…

To what extent did ISIS fighters in Syria end up in Africa? An exact number is impossible to determine — and there was reporting suggesting it was smaller than anticipated — but there were notable Islamic extremist attacks in northern Africa in 2018 and 2019, including a December 26, 2018 bombing of Libya’s foreign ministry, and a January 17, 2019 raid in northeastern Nigeria. And, more recently, an horrific jihadist attack killing 130 people in Burkina Faso further highlights the presence of jihadist ideology in northern Africa.

The ACLED data on African violence in Figure 1 is also illuminating on how the 2011 Arab Spring, along withthe end of the First Libyan Civil War in that same year, may have impacted subsequent violence in Africa’s Sahel region.

According to the ACLED data, in 2011, the Arab Spring saw the number of disorder events increase exponentially in Muslim-majority countries of Algeria (+187%), Libya (+13,220%), Morocco (+1,300%), and Tunisia (+1,964%).

However, the real story may be how violence spread into Africa’s Sahel after the fall of Col. Muammar al-Gaddafi’s Libyan regime in October 2011, when foreign fighters, who had been supporting Gaddafi’s government forces, joined other militant movements or returned to their home countries, well-armed, relatively well-trained and unemployed.

In 2012, of the 12 nations making up the Sahel, nine saw a significant increase in disorder events: Central African Repubic (+90%), Chad (+33%), Ethiopia (+94%), Mali (+923%), Mauritania (+143%), (Nigeria (+161%), Senegal (+83%), South Sudan (+291%), and Sudan (+120%). The three Sahel countries that didn’t see significant rises in violence in 2012 (Burkina Faso, Eritrea, and Niger) did experience increases in 2011 (Burkina Faso and Eritrea) or in 2013 (Niger).

But while most of the Sahel violence has occurred in Muslim-majority countries and many of the rebel groups involved, such as Mali’s militant Islamist sect Ansar Dine, are ideologically linked to al-Qaeda or ISIS, it would be a mistake to assume this rise in violence is only rooted in an Islam versus the Secular World paradigm. In fact, among the 19 African countries with the largest Christian majorities (70 percent+) and Muslims representing less than 20 percent of the population, 13 witnessed significant increases in disorder events in 2011 and 2012 (Angola, Botswana, Democratic Republic of Congo, eSwatini, Gabon, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe).

Along with Islamic State and al-Qaeda aligned militant groups, Africa has a significant number of non-Islamic rebel movements: the Lord’s Resistance Army in Sudan and South Sudan, The Cabinda State Liberation Front (FLEC) in Angola, the Coalition of Patriots for Change in the Central African Republic, and the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (NMLA) in Mali, to name just a few. The NMLA is particularly interesting in that its manpower and firepower increased substantially after the fall of Gaddafi’s Libya and the return to Mali of ethnic Taureg’s who had fought in that conflict.

Violence is rising throughout Africa. That is a fact. As to its sources, any causal model depending solely on the proximate role of Islamic jihadists fails to consider other important factors. Furthermore, it is somewhat laughable to presume there is a “model” that can reliably explain violence (disruptive events) for an entire continent of 1.2 billion people.

Nonetheless, the exercise in trying to build such a model is worthwhile, even if a bit futile in the end.

Possible factors in the rise of violence in Africa

ISIS and other Islamic extremist groups: ISIS is no doubt part of Africa’s violent mix, particularly in northern Africa. But is this marginally cohesive organization really the threat to stability on the African continent, an extraordinarily big place with more linguistic, religious and genetic diversity than any other continent in the world? Considering Sunni jihadist groups have, in the past, been highly dependent on financial support from countries like Saudi Arabia and Qatar, is it perhaps short-sighted to focus on a symptom (such as the Islamic State) rather than a root cause (the Saudi funding and promotion of Sunni Wahhabism)?

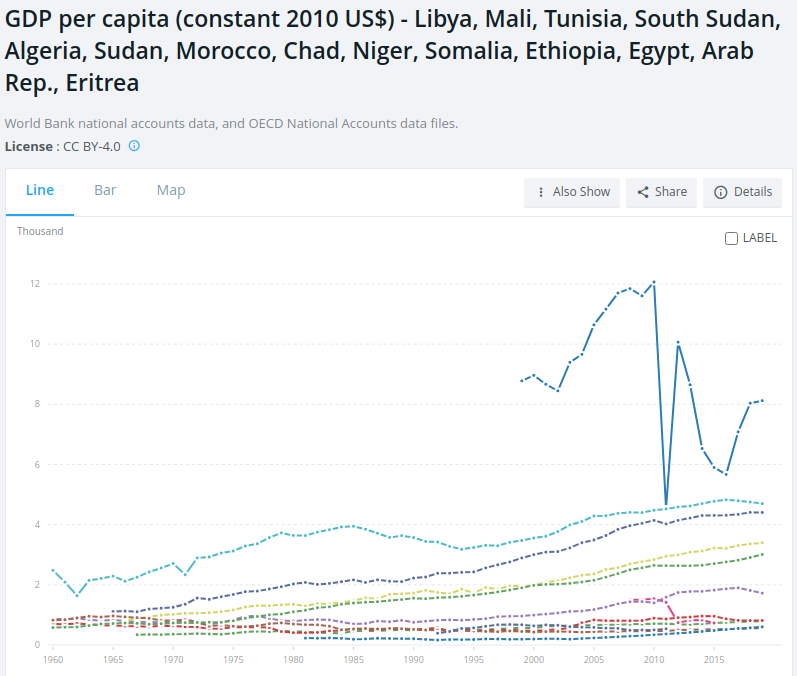

U.S. and European interventions: It is also defensible to recognize the role U.S.-European interference in creating African instability. Academics and analysts have documented the contribution of Libya’s post-Gaddafi instability to the weaponizing of rebel groups in northern Africa and subsequent rises in violence. Once one of the wealthiest African nations prior to NATO’s coordinated military effort to destabilize Gaddafi’s government, the Libyan economy was shattered after his fall (see Figure 2 below where the top line tracks Libya’s GDP per capita since 1999), which had a direct impact on Libya’s poorer neighbors whose economies partially depended on monetary influxes from Libya.

Figure 2: GDP per capita for Libya and selected north African countries over time

In addition, French military operations in Mali since 2013 (such as Operation Serval and Operation Barkhane) have not stopped Islamic jihadists from gaining control of much of northern Mali and a growing resistance from the Mali populace to the French military presence in general.

Any argument supporting U.S.-European interventions in Africa must contend with the reality that such interventions have a checkered record in terms of bringing stability — and that is probably too generous an assessment.

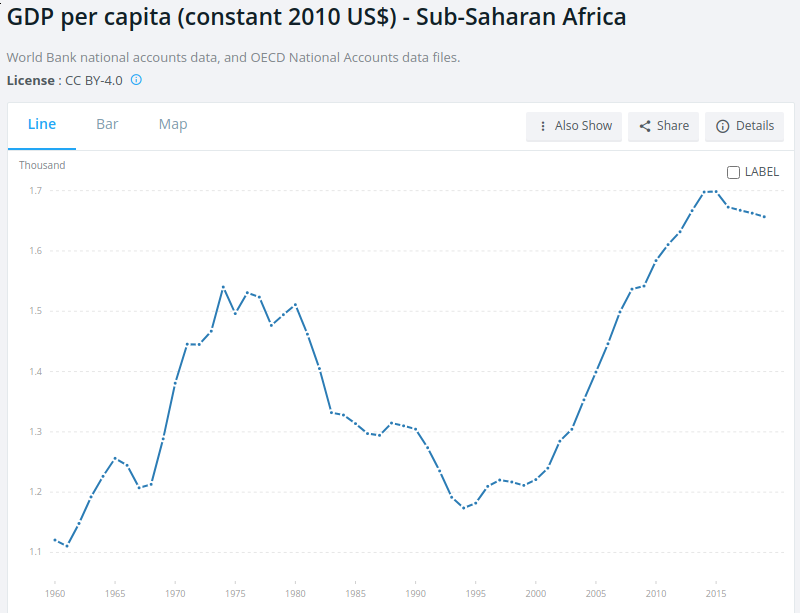

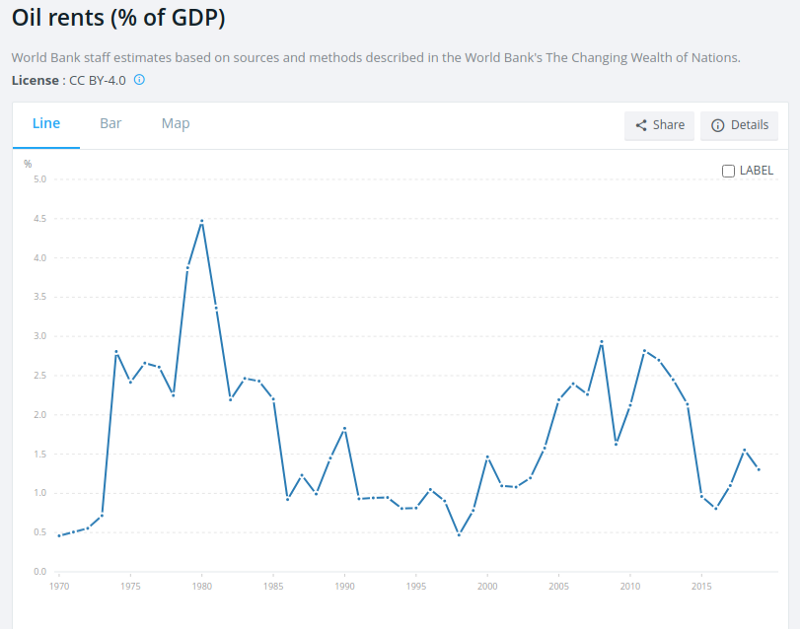

Falling oil prices and economic stagnation: The first 15 years of the 21st-century witnessed an historic economic boom in sub-Saharan Africa, with GDP per capita rising over 42 percent (see Figure 3). At the same time, a relative surge in oil prices also contributed to economic prosperity in oil-producing countries like Libya and Nigeria (see Figure 4).

Figure 3: GDP per capita in Sub-Saharan Africa since 1960

Figure 4: Oil rents (as a % of GDP) since 1970

Unfortunately, the African economies stagnated after 2011, in part due to falling commodity prices and, more generally, the weakened world economy that followed the 2008 world financial crisis.

Quantitative research on political violence and insurgencies has consistently found economic deprivation plays a significant role in the ability of militant groups to recruit soldiers and popularize their movement within a population, particularly when in the midst of local and regional economic inequities and weak political institutions.

In their influential research paper, Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War, Stanford political scientists James D. Fearon and David D. Laitin, who analyzed 161 countries between 1945 and 1999, concluded that:

The factors that explain which countries have been at risk for civil war are not their ethnic or religious characteristics but rather the conditions that favor insurgency. These include poverty-which marks financially and bureaucratically weak states and also favors rebel recruitment-political instability, rough terrain, and large populations.

More recent cross-national research, focused on Sub-Saharan African countries between 1986 and 2004, concluded that the onset of civil conflict is more likely in regions with (1) low-levels of education, (2) strong relative economic deprivation, (3) strong intraregional inequalities, and (4) the combined presence of natural resources and relative deprivation.

Even 2013 research on Boko Haram, a Nigerian Islamist group, by the quasi-governmental U.S. Institute of Peace concluded that: “Poverty, unemployment, illiteracy, and weak family structures make or contribute to making young men vulnerable to radicalization. Itinerant preachers capitalize on the situation by preaching an extreme version of religious teachings and conveying a narrative of the government as weak and corrupt. Armed groups such as Boko Haram can then recruit and train youth for activities ranging from errand running to suicide bombings.”

Striking throughout the quantitative literature on civil wars and regional insurgencies is the lack of significance among ethnic and religious variables in explaining the outbreak of violence.

Contrary to the security establishment sources in the Times article who argue that U.S.-European military support is essential to stemming the rise of militant Islam in Africa, a broader, more objective canvass of sources would have found as many experts arguing the most effective approach to ending the violence would be for increased investments in education, infrastructure, poverty alleviation and good governance initiatives by African governments.

Both arguments can be true, of course. But one would never know that such a contrast in solutions existed if all one had was the New York Times to rely on.

Final Thoughts

In previous posts I’ve lamented the many blind spots that seem to define mainstream journalism today. More disturbing (to me) is the propensity of the national news media to uncritically repeat the opinions of the U.S. national security industry.

If you want to understand why elite media organizations like the New York Times or Washington Post can get so many stories wrong, just look at the sources they continuously canvass for quotes (not to mention their documented willingness to use other journalists as “independent” sources).

How is it possible that the most prestigious, best paid journalists in the U.S. get so many stories utterly wrong?

Nowhere is this problem more apparent than news coverage of international affairs when news organizations incestuously recirculate the same quotes from the monolithic U.S.-European think tank brigade — an insular cadre of career policy analysts and former defense and intelligence officials from places like the Council on Foreign Relations, Human Rights Watch, The Brookings Institute, American Enterprise Institute, Center for American Progress and the Center for Strategic and International Studies — or when they lazily depend on anonymous “intelligence sources” and nameless government officials.

The last place to go for an objective analysis of African defense and security issues are these aforementioned sources. Yet, that is the source of most all mainstream reporting on the topic.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: kroeger98@yahoo.com