By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; June 3, 2021)

“We have not yet finished our mission. But we do not foresee staying indefinitely. Once the sovereignty of Mali is restored, once MISMA (a UN-backed African military force) can replace our own troops, we will withdraw,” the French President told a news conference in Bamako, Mali.

Those were the words of French President François Hollande in February 2013, days after a French-led military offensive had driven Islamist rebels out of the country’s north, except for the city of Kidal.

Eight years later — French troops remain in Mali.

And in that time since President Hollande’s optimistic appraisal of the situation, Mali has weathered two coup d’états — the last occurring a little over a week ago when the Mali military, without resistance from the French military in Mali, detained the country’s president, prime minister, and defense minister. Though widely condemned in formal communiques by the European Union (EU), U.S., African Union and U.N., the likely result of this latest coup is that Mali (with the help of the French) will remain in a constant state of war.

It isn’t just Mali experiencing political instability. Since the 2011 NATO-backed revolt that brought down Colonel Muammar Gaddafi’s dictatorship in Libya, six of Africa’s 10 Sahel countries have seen at least one coup or attempted coup (Mali, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Chad, Sudan and Eritrea).

“The Sahel is on fire,” journalist Bostjan Videmsek wrote in 2016as he covered an emerging Mali refugee crisis.

But it is not just Africa’s Sahel countries that are in turmoil. Since 2011, 30 coups or attempted coups (hereafter, what I call ‘coup events’) have occurred in 17 countries across the African continent.

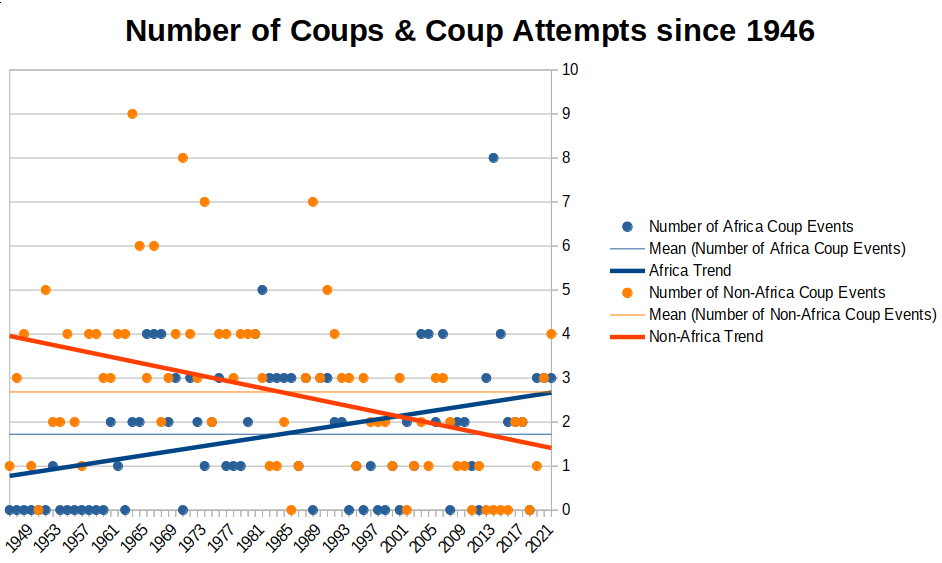

In fact, in the post-World War II period, coup events are on the increase in Africa, in contrast to the rest of the world (see Figure 1). Today, on average, Africa witnesses around three coup events per year; whereas, the rest of the world will have about two. Indeed, even if we remove the outlier year of 2013 from the equation, Africa has seen an increasing trend of coup events since 1946.

Figure 1: Trends in Coup/Coup Attempts since 1946

What is going on in Africa that might explain this troubling trend?

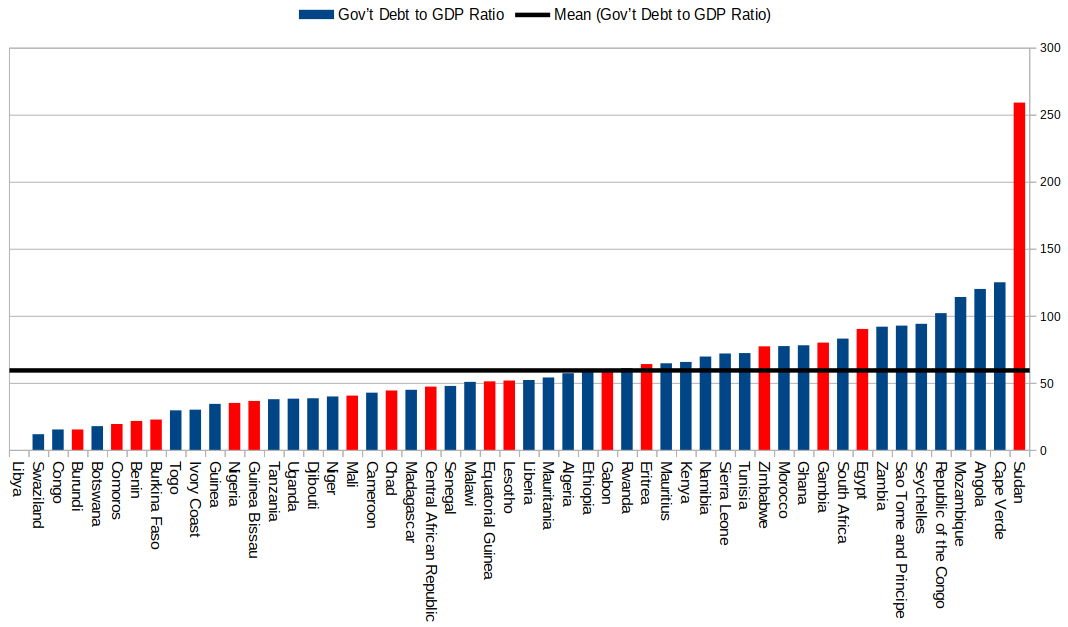

We can rule out one of the standard explanations of African political instability in the 1970s and 80s: government debt.

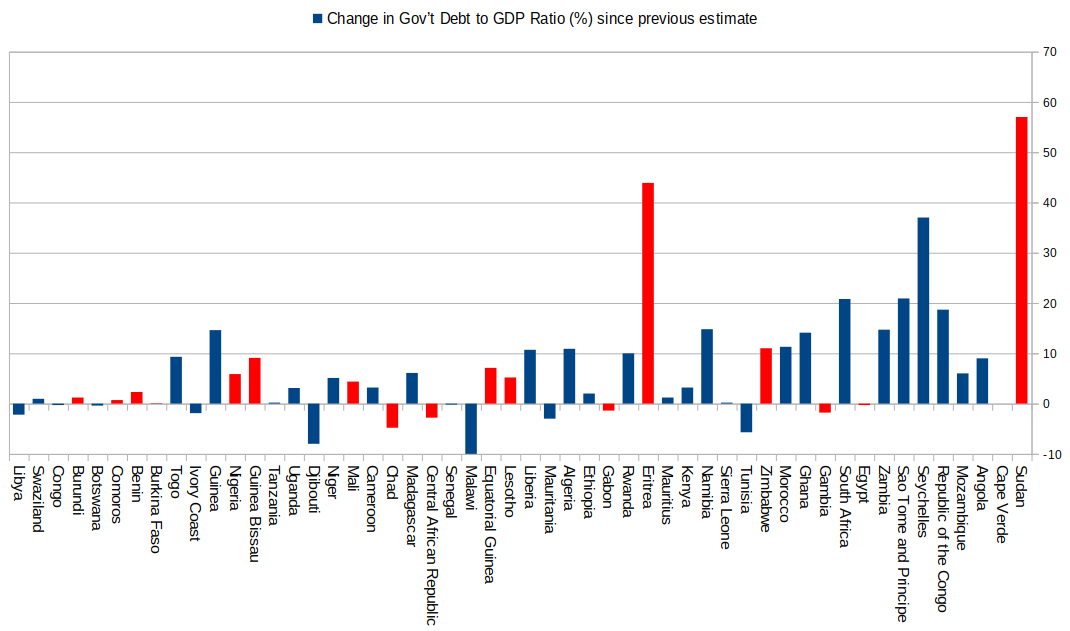

As seen in Figures 2 and 3, the African countries with significant coup events in the past 10 years exist across the entire indebtedness spectrum. While the most indebted country — Sudan, at over 250 percent of GDP — has also been one of the most politically volatile, some of the least indebted countries have likewise seen significant coup events in this period: Burundi, Comoros, Benin, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Chad, and the Central African Republic.

Figure 2: Gov’t Debt to GDP Ratio (%) for African countries (2019/2020)

Figure 3: Change in Gov’t Debt to GDP Ratio (%) for African countries

Extreme debt financing burdens to foreign creditors can stunt economic growth and compel governments to divert money from critical social services, leading to increased social instability. But that does not seem to be the major driving force today — at least not the debt part of the equation.

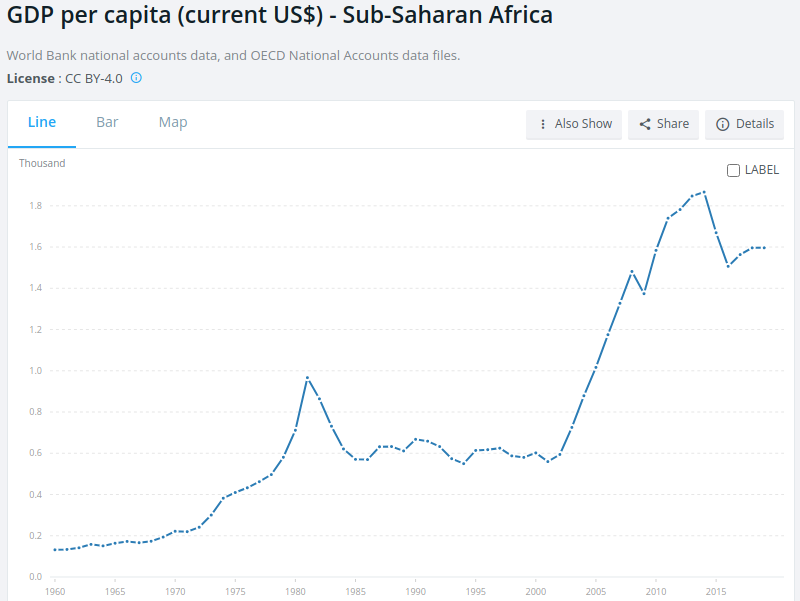

Instead, in the past decade, oil-exporting African countries have endured declining petroleum prices — which have been in a general decline since a $139 peak (for West Texas Intermediate crude) in 2008 — while sub-Saharan African countries have seen their spectacular GDP-per-capita growth of the 2000s start to stagnate (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: GDP per capita growth in Sub-Saharan Africa since 1960

In his 1970 book, Why Men Rebel, political scientist Ted Gurr introduced the concept of relative deprivation, which he defined as the discrepancy between what people think they deserve, and what they actually think they can get.

“The potential for collective violence varies strongly with the intensity and scope of relative deprivation among members of a collectivity,” wrote Gurr.

Though Gurr’s thesis since has been significantly modified — with a society’s capacity for political violence being one major addition to the model — it still offers useful insights.

It is well-known that Africa is resource rich (see Figure 5). The African continent accounts for 20 percent of the world’s land mass, 17 percent of its population, and 3 percent of the its GDP — but contains 30 percent of the world’s remaining mineral resources.

While it is inaccurate to assume Africa’s resource wealth is the only reason for the continent’s strong economic growth in the 2000s, it was a major factor in China’s strategic decision to invest heavily there in the past 20 years (see Figure 6).

Figure 5: Mapping Africa’s Natural Resources

Figure 6: U.S. and Chinese Foreign Direct Investment to Africa since 2003

Yet, as of late, China’s investment in Africa has waned, which has played a role in Africa’s dampening economic growth.

Taken together, stagnate growth amidst rising expectations caused by the 2000s economic boom period cannot be discounted when explaining Africa’s current political instability.

But such a conclusion neglects the elephant in the room — the negative impact of NATO’s and the Barack Obama administration’s destabilizing of northern Africa — says policy analyst Robert Morris, author of Avoiding The British Empire: What it Was, and How the US can Do Better.

How NATO and the U.S. mucked up Libya (and Syria)

“The destruction of Libya was key to the refugee flows that destabilized the European Union in 2014, and led to the loss of one of its richest countries (United Kingdom) with Brexit in 2016,” contends Morris. “The effects Of Gaddafi’s killing on the Sahel were both immediate, and long lasting. The financial network that had come to underpin the prosperity of much of North Africa disappeared. Gaddafi’s African soldiers dispersed back to their countries and took their weapons with them. Mali was the first to fall.”

It should be reminded also how many of the weapons from the 2011 Libyan revolt found their way to Syria and its civil war. Over 400,000 Syrians have died in Syria’s ongoing civil war and the U.S. remains entrenched in the country’s northeastern sector, presumably to protect Syrian Kurds, but as we know from Trump’s irrepressible candor, the purpose is largely to control much of Syria’s vital oil and gas reserves and thereby control Assad’s ability to rebuild his war-torn nation.

In the final analysis, the West’s weaponizing of the Libyan civil war had a direct and indirect relationship to coup events in Africa’s Sahel, the Syrian civil war, and the refugee crisis in Europe.

Those results alone establish how bad Obama’s Libya policies were during the Arab Spring of 2011.

As unstable as Gaddafi may have been, Libya under his leadership was becoming an economic powerhouse by African standards. Up to 2011, oil money from Libya was spreading throughout Africa.

And then came the Arab Spring of 2011 and, more importantly, the West’s interference in its progress.

“NATO scooped out North Africa’s economic heart and set it on fire,” argues Morris. “After Libya’s destruction, every economy in the Sahel came to a screeching halt.” Before 2011, Libya’s GDP per capita exceeded European Union countries such as Romania and Bulgaria, notes Morris. Today, Libya struggles to reestablish political stability so that it can, once again, become one of Africa’s most prosperous countries.

The “Iraqification” of Africa by Biden and the EU

In the midst of political instability in the Sahel, the European Union (EU) has recently dedicated €8 billion Euros to its European Defense Fund (EDF) that will fund new military weapons and technologies for militaries within the EU and launched the European Peace Facility (EPF) that will authorize the EU for the first time to supply military weapons — along with equipment and training — to non-European military forces around the world.

A reasonable assumption is that significant amounts of these EU-funded weapons will go to military operations in northern Africa, such as in Mali.

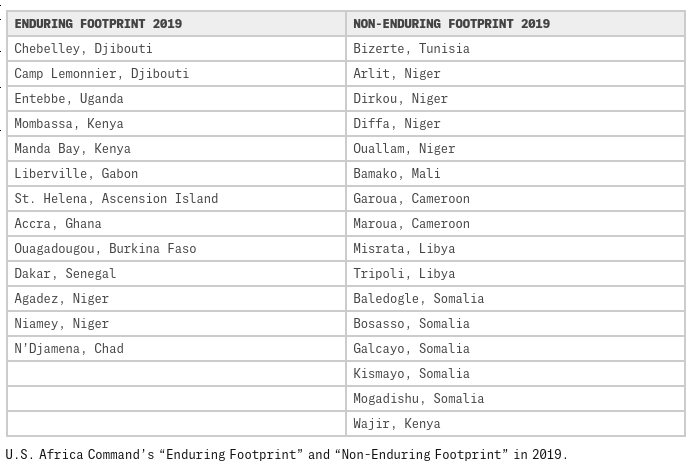

The U.S. military, of course, already has a significant presence throughout Africa, including 29 bases and installations (see Figure 7). Ten years ago, that list would have had around 10 bases and installations.

Figure 7: U.S. military bases and operations within Africa (as of 2019)

For the most part, Trump neglected African issues, and by the end of his term was pulling U.S. forces out of countries like Somalia — to the vocal consternation of the Washington, D.C. neoliberal and neoconservative establishment.

Trump’s troop withdrawals are a direct threat to African stability, moaned more than a few media elites and foreign policy analysts, who conveniently ignored the fact that today’s growing instability in Africa correlates to the increased engagement of the U.S. military on the continent. When the U.S. military stood up USAFRICOM at the end of the George W. Bush presidency, one of its first operations under Operation Enduring Freedom (“The Global War on Terror”) was a joint effort by the U.S. and NATO to “stabilize” the Saharan and Sahel regions of Africa at the start of the Libyan civil war in 2011 (U.S. military activities in the Sahel also fall under Operation Juniper Shield).

Instead of stabilizing the region, the U.S. and NATO further weaponized it. There are currently about 40 million guns and light weapons circulating among civilians in Africa, according to one UN report (https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/december-2019-march-2020/silencing-guns-africa-2020). Government entities hold around 11 million guns and light arms, according to that same report.

Since the start of his presidential candidacy, Joe Biden has hinted at a more active U.S. role throughout the world (not just Africa), and if the past is prologue, this will mean deeper U.S. military engagements.

Evidence of his intent came in April when the Biden administration tapped Jeffrey Feltman, a former senior U.S. and United Nations diplomat known for his advocacy of robust U.S. interventionism, to be the U.S. special envoy to the Horn of Africa — an area where Islamist groups remain a palpable threat to regional stability and where growing tensions between Ethiopia and Sudan threaten to further add volatility to the region.

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken highlighted the latter issue when announcing Feltman’s appointment: “Of particular concern are the volatile situation in Ethiopia, including the conflict in Tigray; escalating tension between Ethiopia and Sudan; and the dispute around the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.”

Where Trump made few promises to African leaders and they responded by not asking for many, Biden has invited the opposite dynamic.

The Biden administration hadn’t moved in yet when former Somali Prime Minister Abdi Yusuf openly pleaded to the Biden administration to recommit to “protecting Somalia” from al-Shabab and other Islamist groups.

Feltman’s appointment and other policy signals from the Biden administration, such as recent State Department allegations of human rights abuses in Ethiopia and designating insurgent groups in Mozambique and the Republic of the Congo as terrorist organizations, shows the U.S. wants once again to be the world’s school hall monitor, or in less snarky terms, “an international voice of conscience.” Consonant with the State Department’s declaration on Mozambique-based terrorist groups, the U.S. military is now actively training Mozambique security forces.

But before assuming only altruistic motives by the U.S., the French oil and gas company Total (TOTF.PA) recently announced it will restart construction of its $20 billion liquefied natural gas project in Mozambique given the improved security situation, having withdrawn its workforce from northern Mozambique in January because of security concerns. Total’s demand for a 25 kilometer secure buffer zone around their project site has been accepted by the Mozambique government, in part due to U.S. security assistance.

These U.S. (and French) policy moves in Mozambique have led some Africa watchers to warn of the “Iraqification” of Africa. In other words, the U.S. is creating an expanding, self-justifying military presence with open-ended mission goals tracked by fuzzy performance metrics.

Africa policy observer Jasmine Opperman says of U.S. and French current policies in Mozambique: “The worst…would be an intervention, direct or not, of the great powers.”

Yet, that is exactly what the Biden and Macron governments are in the process of doing.

There are still reasons for optimism in Africa

But despite the Biden administration’s predictable ramping up of U.S. involvement in Africa’s most intractable military conflicts, many foreign policy analysts, like Morris, remain optimistic for Libya and other African countries.

For starters, after years in which rival groups in Libya asserted their legitimacy as the country’s rightful government, the parliament approved a national unity government on March 10, headed by Prime Minister Abdul Hamid Dabaiba. The transfer of power was peaceful. Something that can never be taken for granted.

Due to Libya’s oil wealth, when it is stable, it is central to all of the Sahel economies, including Tunisia, which still has a functioning (though fragile) democracy. Prior to the Libyan civil war, money sent home from migrant work in Libya was a big part the economy of all Sahel countries. That source of stability may soon return.

“Libya’s population is rich and educated enough, that it’s easy to imagine Tunisia’s experiment spreading there if stability can be preserved,” asserts Morris. “Algeria and Morocco are both relatively rich, fairly well organized places that are very ready for a new system. With a stable Libya, Tunisia could lead a North African block into democracy. This stability wouldn’t just shut down refugee flows, it would provide a new platform for cooperation and economic development, which would, in turn, lead to stability and prosperity for the whole of the Sahel.”

“The Sahel can be a resource for the world’s diplomats and business people again, instead of just a profit center for the French and U.S. militaries,” says Morris. “This isn’t just possible, it’s the most likely result if Libya manages to stabilize.”

Now if only the U.S. and France don’t find a way to screw up this progress.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: nuqum@protonmail.com