By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; March 17, 2022)

“Truth is what you get other people to believe.” — Tommy Smothers

Larry Diamond, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution and at the Freeman Spogli Institute at Stanford University, summarized the mainstream view of Vladimir Putin’s Russia by the American foreign policy and defense establishment in a 2016 article for The Atlantic:

“Since the end of World War II, the most crucial underpinning of freedom in the world has been the vigor of the advanced liberal democracies and the alliances that bound them together. Through the Cold War, the key multilateral anchors were NATO, the expanding European Union, and the U.S.-Japan security alliance. With the end of the Cold War and the expansion of NATO and the EU to virtually all of Central and Eastern Europe, liberal democracy seemed ascendant and secure as never before in history.

Under the shrewd and relentless assault of a resurgent Russian authoritarian state, all of this has come under strain with a speed and scope that few in the West have fully comprehended, and that puts the future of liberal democracy in the world squarely where Vladimir Putin wants it: in doubt and on the defensive.”

Replace the word “Russian” in the above excerpt with “Iranian” or “Venezuelan” or “Chinese” or “Islamic” and you’ve captured the essence of U.S. security policy since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991: Protect existing liberal democracies, guide others into becoming one, and isolate those that resist the transition.

And have we been successful?

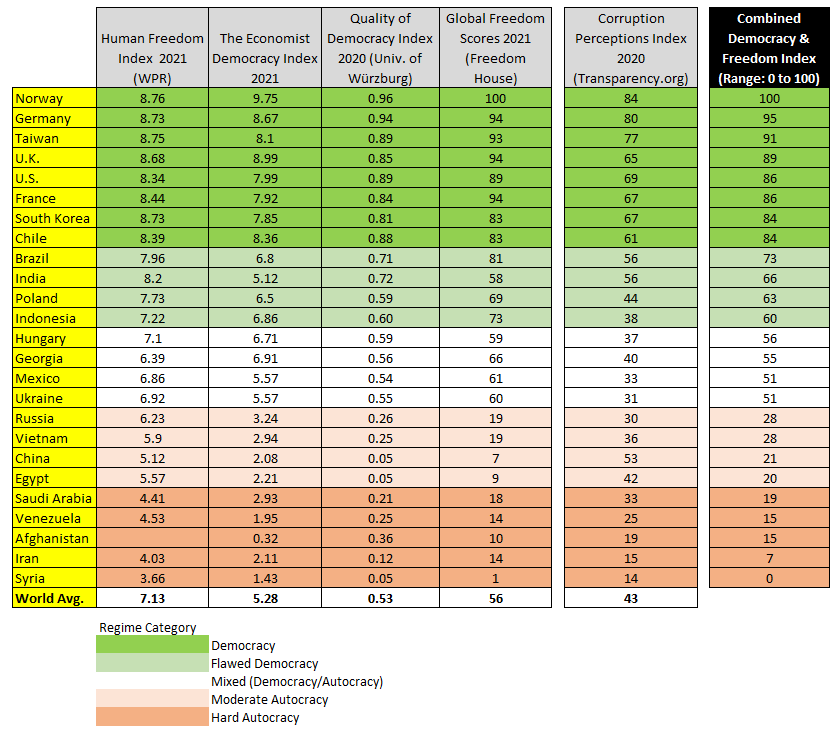

Figure 1 shows democracy/freedom indices that summarize current freedom levels for a selection of countries — the sum of which account for over half of the world’s population.

If the existing freedom and democracy landscape is any indication, there are tremendous success stories on display. Taiwan, South Korea, Chile, Brazil, Poland, and Indonesia are good examples of countries who have made successful transitions to democracy since the 1980s. Many of these new democracies remain fragile; but, apart from China and Russia and their few confederates, variations in the liberal democratic model dominate the international order today. If our time frame is the last 40 years, the conclusion remains that it is autocracies that not only are on the run, but cornered and isolated.

Figure 1: Freedom/Democracy Indices for Selected Countries (2020/21)

Data sources:

Human Freedom Index 2021 — World Population Review (https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/freedom-index-by-country)

The Economist Democracy Index 2021 (https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2021/)

Quality of Democracy Index 2020 — Univ. of Würzburg

(https://www.democracymatrix.com/ranking)

Global Freedom Scores 2021 — Freedom House

(https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2021/democracy-under-siege)

Corruption Perceptions Index 2020 — Transparency.org

(https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2020)Combined Freedom Index computed by the author (K. Kroeger)

But if our time-frame is shorter, it is also apparent that liberal democracies aren’t thriving either.

As Figure 1 suggests, some countries often portrayed as “liberal democracies” in the news media are, in fact, significantly below the standards of full democracies. A noteworthy number of them are former Warsaw Pact countries (e.g., Hungary) and former Soviet Republics (e.g., Armenia, Ukraine, Georgia) — which are often called ‘hybrid’ systems as they combine characteristics from both authoritarian and democratic systems.

Common among their growing democratic deficiencies is increased governmental control of the justice system, civil society, and media, while rolling back many basic human and political rights, according to separate reports by the Civil Liberties Union for Europe, which is a Berlin-based civil rights advocacy group, and Economist Intelligence. The targeted harassment of migrant and minority groups especially has been on the rise in many of these countries.

Despite the sweeping goodwill generated by the international community’s near-unanimous condemnation of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, can it be interpreted as an endorsement of liberal democratic ideals? Given the recent backtracking on liberal democratic principles by many of the countries now censuring Russia, it is hard to conclude one has anything to do with the other.

Are full democracies a dying breed?

At the end of the original Cold War, political scientist Francis Fukuyama conjectured: “What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War … but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind’s ideological development and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”

Fukuyama has since pulled back from his original optimism, and as we stand on the brink of a new Cold War, it may be fair to wonder if we are witnessing the slow death of liberal democracies instead of their immutable primacy.

The Canadian government’s ability (and craven willingness) to freeze the bank accounts of truckers who organized or blocked roads in a three-week protest over the nation’s COVID-vaccine mandates indicates freedom and democracy are not immutable conditions.

According to Economist Intelligence (EIU), which ranks Canada as the 12th most democratic country out of 167 countries, Canada’s EIU Democracy Indexscore dropped 3 percent between 2020 and 2021 (i.e., during the pandemic).

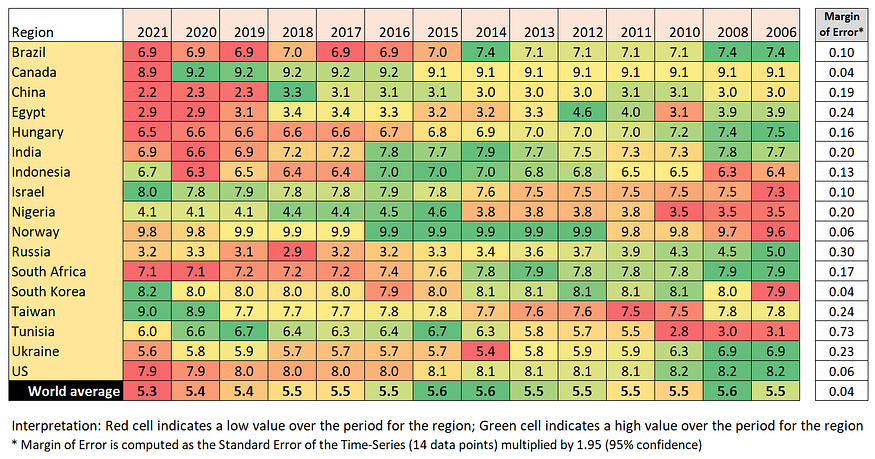

If Canada can backslide on democracy, even if just in the margins, any country can. And, over the past 30 years, the world has witnessed cases many such cases: Democratic experiments that failed spectacularly include Egypt, Russia, and Venezuela, while some more successful new democracies like Brazil, Hungary and South Africa have experienced smaller, but significant, declines in civil freedoms — and add a disheartening coup in Tunisia last year, one of the few democracies in the Arab world.

We see these democracy declines in Figure 2 which shows changes in the EIU Democracy Index since 2006 for seven world regions. Since 2006, the EIU Democracy Index declined in every region except Asia/Australasia.

Figure 2: Economist Intelligence’s Democracy Index (2006 to 2021)

Democracy is on the run in many places…but not everywhere. Figure 3 offers some positive examples where democracy and freedom are on the rise.

Since 2006, the most consistent increases in EIU Democracy Index scores occurred in Israel (+0.7), South Korea (+0.3) and Taiwan (+1.2). And despite score declines since 2015, Indonesia and Nigeria nonetheless score significantly higher on the EIU Democracy Index today than they did in 2006 (+0.3 and +0.6, respectively).

Figure 3: Economist Intelligence’s Democracy Index— Selected Countries

Methodological issues

Are small changes (e.g., ±0.1)in the EIU Democracy Index truly significant? From a statistical perspective, the average margin of error (i.e., standard error multiplied by 1.95) for the 167 countries in the EIU dataset was ±0.16 — which is why, to be conservative, I only report changes of 0.3 points or higher in this essay.

However, before accepting the democracy/freedom indices discussed here, realize the substantial criticisms of these indices.

The criticisms include (but are not limited to):

- Universalism versus relativism: Is democracy a universal concept understood the same way worldwide or is its understanding relative to the culture or context in which it operates? If it is a relative concept, summarizing it using one index across all countries is problematic.

- Temporality: The concept of modern democracy has evolved over time. To the Greeks, it meant “rule by the people.” Post-American Revolution, the definition added consideration of constitution-based rights and protections, and post-WWII, the importance of free market liberalism became essential. And at what extent do these democracy/freedom measures consider the relevance of people’s freedom from worries over the availability of quality health care, housing and education? The point is that comparability over time, including potentially short periods of time, cannot be assumed for any democracy/freedom measure.

- Non-normality: Most democracy indices are not normally distributed when all countries are tabulated. This is not necessarily a problem if that is how the world’s political systems are distributed, but if a researcher wants to use distribution-based statistical methods to test hypothesis, non-normality makes analyses somewhat thorny.

- Interchangeability: “Different measures of democracy can lead to substantially different findings and interpretations,” according to Andrea Vaccaro, a former PhD Fellow at United Nations University’s World Institute for Development Economics Research whose research focuses on cross-national measures of democracy and state capacity.

Faced with the problems inherent in cross-national democracy measures, particularly interchangeability, Vaccaro concludes, “To overcome problems related to weak interchangeability, if a single measure cannot be credibly chosen on theoretical grounds, this author recommends users of the measures to validate their findings with multiple measures of democracy.”

Any single democracy/freedom index or aggregate combinations of them must be viewed with abundant caution, particularly given their likely normative bias that favors the liberal (“free market”) democratic model. For this reason, it is best to view the data presented in this essay as evocative rather than definitive.

Is the Russia-Ukraine war part of the democracy-authoritarianism struggle? Probably not…

Attempting to explain the timing of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau recently surmised that democracies weakened through the spread of misinformation on social media prompted Putin’s decision:

“We see a bit of a slippage in our democracies — countries turning towards slightly more authoritarian leaders, countries allowing increasing misinformation and disinformation to be shared on social media turning people against the values and the principles of democracies…unfortunately (this) emboldened Putin to think that he could get away with this (invasion of) Ukraine.”

An emboldened Putin invaded Ukraine because of misinformation on social media?

That is an adventurous (reckless) claim given the evidence is substantial in other directions as to why democracy has experienced significant declines over the past decade. Near the top of that list is the COVID-19 pandemic:

“The pandemic has had a negative impact on the quality of democracy in every region of the world,” concludes EIU in their 2021 report. No world leader should know that better than Trudeau. Among the most advanced economies, only Italy and Greece have implemented more draconian pandemic restrictions than Canada, according to Oxford University’s Covid-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT).

The other major stresses on democracy over the past decade have been declines in press and religious freedoms (civil liberties), political party financing increasingly dependent on wealthy elites, lack of government transparency, financial profiteering by political elites, and low accountability (e.g., incumbency advantage). “Citizens increasingly feel that they do not have control over their governments or their lives,” says the EIU 2021 report.

Could social media have contributed to citizens’ awareness of these deficiencies in their country? Absolutely.

Does some of the information passed through social media contain misinformation? Of course, as happens through establishment information sources as well.

But did social media and the misinformation passed through it break down democracies to the point Putin decided now was the time to invade Ukraine?

All I can say is, Mr. Trudeau, show us your data.

To my eyes and ears, Mr. Trudeau’s causal model seems dubious and, most likely, untestable. Ivermectin has more quantitative support than his “social media has weakened our democracies and therefore Putin attacked”-thesis. But that didn’t stop him from throwing his geopolitical folk theory into the social ether.

Trudeau’s message is clear: Canadians, if you disagree significantly with me, by definition, you are spreading misinformation and must be stopped. In other words, according to Mr. Trudeau, censor dissenting views by any legal means possible.

But it is not just in Canada. Increasingly, political (and media) elites across the globe are endeavoring to control the content and flow of information under the guise that only “they” know the truth. The democracy/freedom indices cited in this essay offer indirect but suggestive evidence of this reality.

However, such an elitist worldview as expressed by Trudeau (and others) defies the well understood dynamic on how human knowledge advances —Knowledge growth is both a bottom-up as well as a top-down process. Killing one half of the process, kills both sides.

But Trudeau is only doing what democratically-elected leaders across the world are attempting to do (and increasingly succeeding at) — controlling the information allowed to disseminate over the general population.

The prevailing belief among the political class is that controlling information is tantamount to controlling their own prosperity and destiny. On that point, they are probably correct.

But if the wider goal is to protect our liberal-democratic principles and institutions, then I contend that the most dangerous threat to their existence is not Vladimir Putin’s Russia or misinformation found on social media, but rather the political and economic elites that dominate the liberal-democratic landscape.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: kroeger98@yahoo.com