By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, March 13, 2018)

{Send comments to: kkroeger@nuqum.com; the SPSS dataset used in this article can also be provided upon request}

“We conducted an election that had integrity,” said CIA Director Mike Pompeo and soon-to-be Secretary of State during a public event last October. “And yes, the intelligence community’s assessment is that the Russian meddling that took place did not affect the outcome of the election.”

Unfortunately, no U.S. intelligence agency has ever publicly addressed the question about whether the Russians affected the outcome, much less answered it to the degree Pompeo implied.

We still don’t know if Russian meddling affected the outcome of the 2016 presidential election and there is an excellent chance we will never know with certainty.

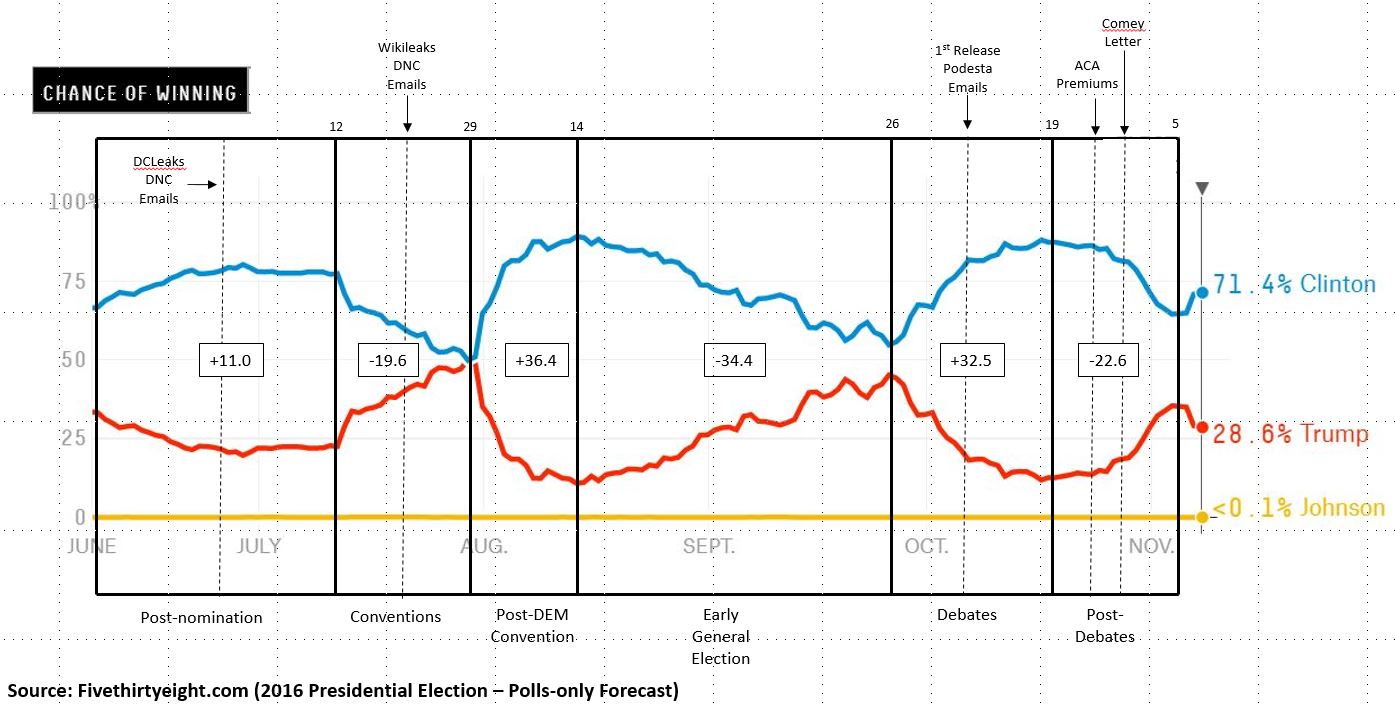

In past posts, we expressed skepticism that $30-40 million of Russian-backed social media advertising, no matter how well spent strategically, could alter a U.S. presidential election where the two major campaigns spent over a billion dollars. Even the releases of the DNC and Podesta emails, also products of Russian meddling, do not directly correlate with any changes in tracking polls or prediction markets. Obviously, the email leaks could still have been very important in that they drove daily news coverage for consecutive days and prevented the Clinton campaign from generating momentum.

“To drive a wedge between Democrats just as we were coming together after the primary, Russian hackers stole and selectively published files from the Democratic National Committee,” Hillary Clinton told one of her book tour audiences last October. “It was a virtual Watergate break-in. Later, to blunt our momentum, and distract from the Access Hollywood tapes, they released emails stolen from my campaign chair, John Podesta.”

Clinton’s contention has significant merit. The DNC and Podesta emails hurt her campaign. But as the fivethirtyeight.com election forecasts show in Figure 1, both the first release of the DNC emails (by DCLeaks in early July 2016) and the Podesta emails on Oct . 7, 2016 were followed by either stable or increasing poll numbers for Clinton. Only the Wikileaks release of the DNC emails in mid-July was followed by a decline in Clinton’s poll numbers, but even that trend started days before the Wikileaks release. The DNC and Podesta email leaks very likely changed the campaign’s dynamics, but it will be difficult to prove how they changed the final outcome.

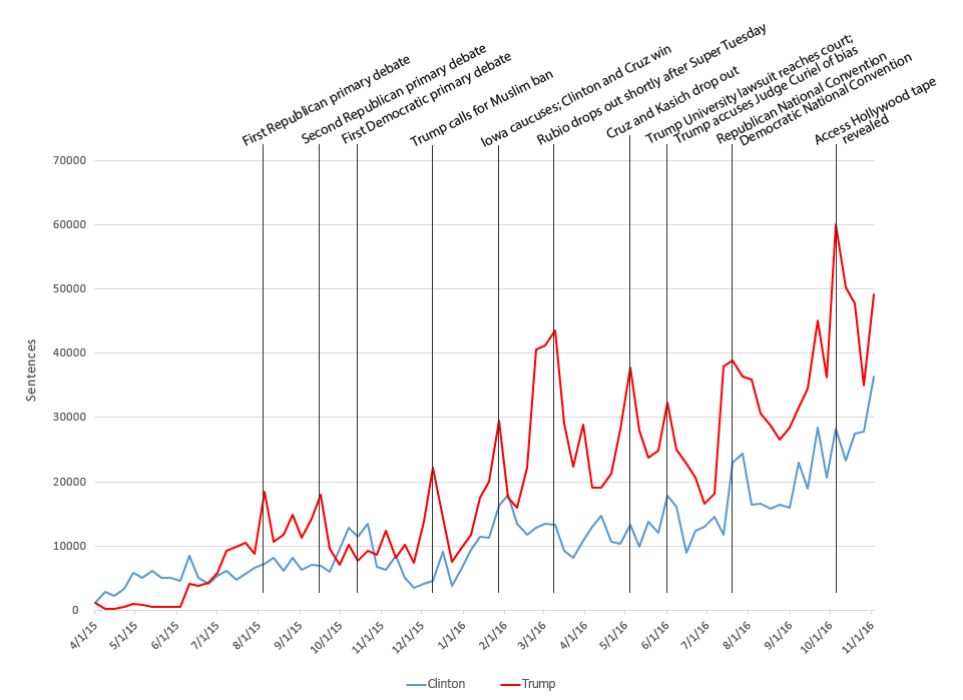

Before identifying nuanced factors behind the 2016 outcome, it is important to identify the most potent factors first, and at the top of that suspect list is the $1.2 billion advantage in “free media” the major mass media gave Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton.

Hours of unfiltered television coverage of Trump rallies in front of enthusiastic crowds, particularly during the primaries, were a priceless gift to the Trump campaign (see Figure 2).

Explaining Trump’s stunning election victory must therefore begin with the news media’s pursuit of an audience; and nothing attracted an audience during the 2016 campaign like Donald Trump. From earliest moments of the campaign the news media incubated and nurtured the Trump campaign with hours of unfiltered coverage of his campaign speeches and rallies. Through this coverage, Trump gained credibility and relevance.

According to media analyst Andrew Tyndall, by March 2016, Trump accounted for nearly a third of all election coverage and more than all Democratic candidates combined. And the mass media couldn’t have been happier as the Trump coverage translated directly into larger audiences and larger profits.

And nobody was happier than the cable news networks.

And the main attraction was Trump.

Do you want to understand why Donald Trump won the election? Start your inquiry with the cable news networks.

But that doesn’t let the Russians off the hook.

Any attempt to measure Russia’s unique impact on the election must also contend with the multitude of competing campaign communications that flooded the daily news cycle. And it doesn’t help that the messages and social media tactics used by the Russians paralleled what was already coming out of the Trump campaign. To tease out a causal link attributable to only the Russians may be no more than the digital age version of a snipe hunt.

All the same, the Russians did lay down some markers during their social media campaign, most notably a series of Facebook group pages that may have generated collateral behaviors such as Google searches which may offer indirect evidence of the Russians’ impact.

And that is where the search for the Russians’ influence on the 2016 election begins.

Killary and the “Heart of Texas”

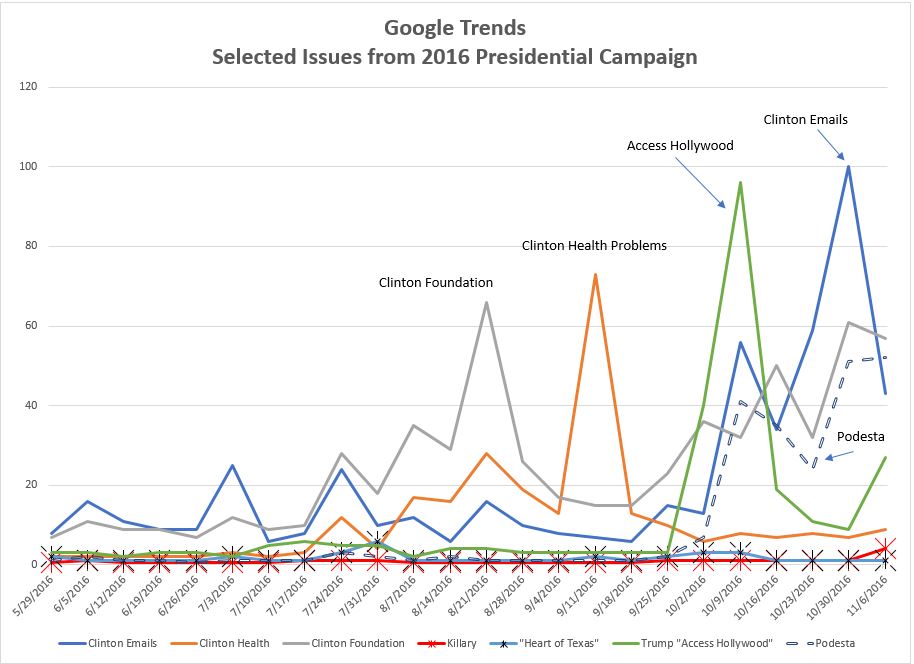

Using Google’s Trends service — which allows the public to discover trends in Google searches — we found two terms over the course of the 2016 campaign that we attributed to the American public’s interest in two Facebook group pages created by Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA): “Killary” and “Heart of Texas.”

The terms “Killary” and “Heart of Texas” — shown in the Figure 3 with star markers (X) — barely registered in Google searches relative to the major campaign issues: Clinton emails, Clinton health, Clinton Foundation, Access Hollywood tape, and the Podesta emails. The index scores (which can range from 0 to 100) for “Killary” and “Heart of Texas” never exceeded 10 during the course of the election. In comparison, “Clinton emails” had a weekly index score over 40 four times during the campaign.

Even so, is there is a noticeable peak in “Heart of Texas” Google searches during the Democratic National Convention in late July and a peak in “Killary” searches in the last week of the campaign, which only proves the Russians had a barely discernible impact on Google searches.

The 2016 American National Election Study

Feeling slightly more confident after exploring Google Trends, we decided to leverage some of the public opinion data available online, more specifically, the 2016 American National Election Study conducted during every national election by The University of Michigan and Stanford University. Their data is available to the public here.

We must state upfront: The 2016 American National Election Study (ANES) was not designed to measure the impact of Russia’s meddling in the 2016 presidential election.

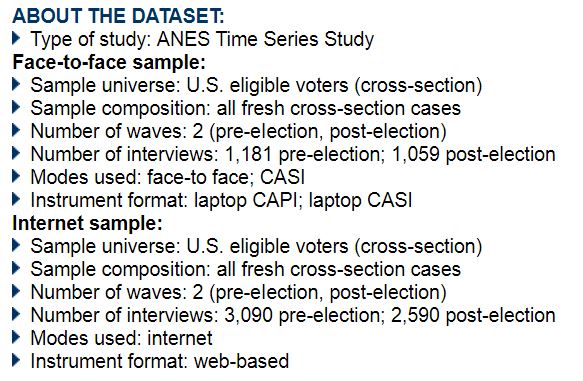

[A detailed description of this nationally-representative survey conducted by The University of Michigan and Stanford University during every national election can be found in Appendix A.]

Social science inquiry is hard enough when a study is specifically designed to measure precise empirical questions, but when they are not, conclusions are often heavily qualified.

That will be the case here.

The following analysis shows that over the course of the 2016 campaign there were attitudinal differences in specific segments of the population consistent with the hypothesis that Russia’s social media efforts, particularly the memes portraying Clinton in a negative light, targeted older conservatives otherwise open to voting for Clinton.

We cannot say for certain that Russian meddling is the cause of these attitudinal differences. And, in fact, the first suspect must be the overall partisan nature of social media itself. A recent Harvard study of the 2016 elections found Facebook and Twitter to be highly partisan social media platforms and a person’s ideological orientation largely determined what platforms they used and what information they consumed.

Before we blame the Russians for strengthening partisan differences in Americans’ evaluations of Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, we must account for the broader impact of social media in general.

Furthermore, the objective evidence that the Russians even engaged in such detailed social media targeting is minimal and comes largely from Facebook’s internal analysis of Russian-sourced content during the 2016 election.

Nonetheless, it is interesting that older conservatives that used social media for sharing political information were significantly more negative in their attitudes towards Hillary Clinton.

Either they were unusually susceptible to negative information about Clinton found on social media, or they were targeted with negative political information about Clinton…or both.

In the 2016 election, older conservatives that used Facebook/Twitter for sharing political information had particularly negative views of Clinton

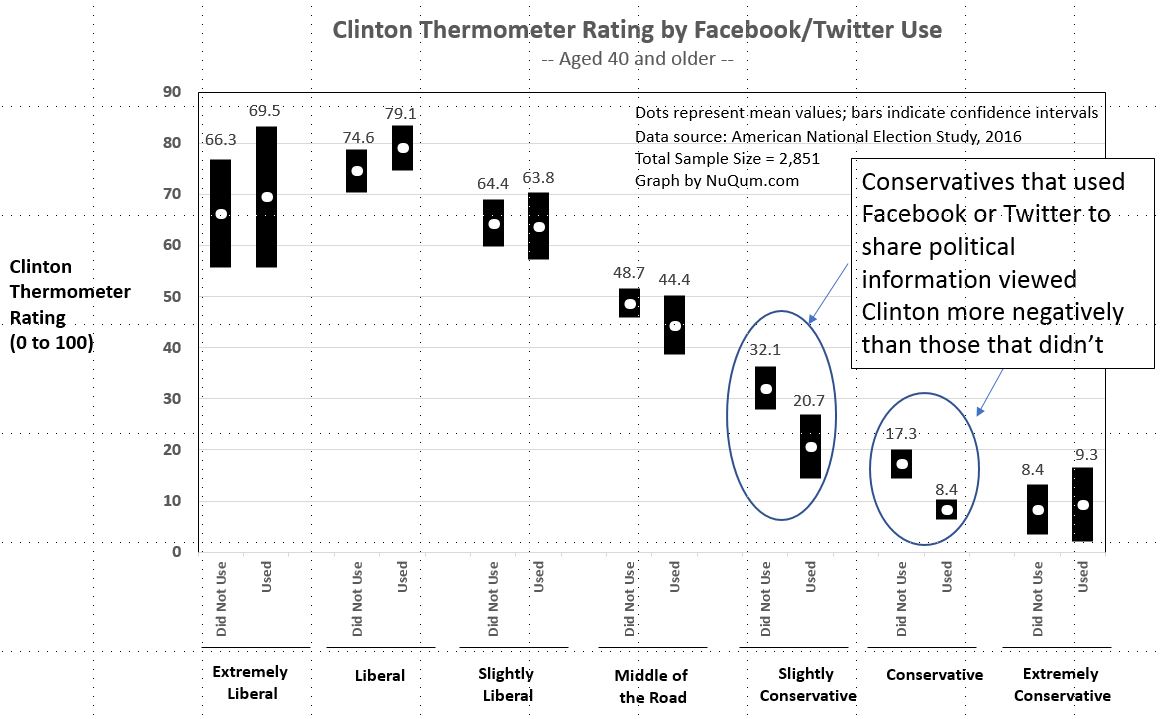

With those caveats in mind, our analysis of the 2016 ANES shows preliminary evidence that, among politically conservative adults over 40-years-old, the use of Facebook and Twitter for sharing political information during the 2016 election correlated with significantly more negative opinions and impressions about the Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton, both in absolute terms and relative to the Republican candidate Donald Trump.

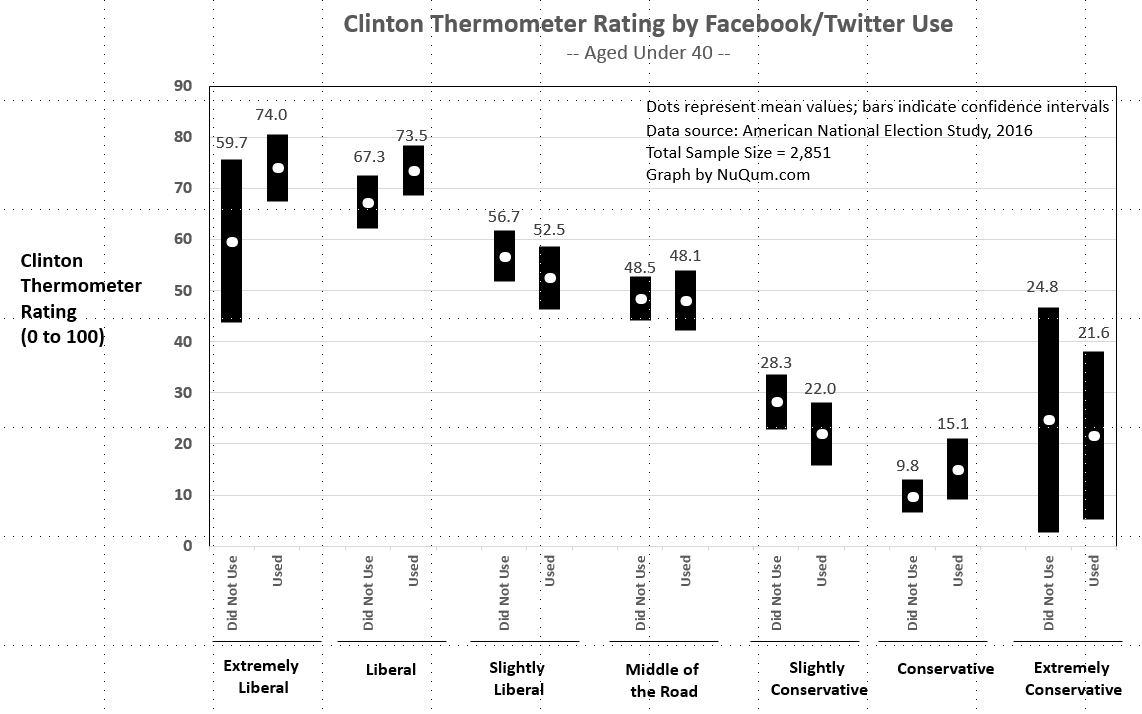

In rating Hillary Clinton on a 0 to 100 favorability scale, “slightly conservative” adults aged 40 or older who used Facebook or Twitter to share political information, on average, gave her a rating of 20.7, compared to 32.1 among otherwise similar adults who had not used Facebook or Twitter for sharing political information (see Figure 4 below). A similar relationship emerged among “conservative” adults (aged 40 or older). This pattern did not appear however among adults under 40 years of age, regardless of political ideology.

“Slightly conservative” and “conservative” Americans accounted for 25 percent of the U.S. vote eligible population according to the 2016 ANES. And within that 25 percent, just under half of them said they used Facebook or Twitter to share political information during the campaign.

That is still almost 12 percent of the population that had a distinctly more negative view of Clinton by the end of the campaign, compared to other eligible voters with otherwise similar demographic and attitudinal characteristics.

We believe something unique happened to this group during the campaign. We can’t call it a “Russian effect” but we feel somewhat comfortable calling it, for now, the “Facebook-Twitter effect” (FTE).

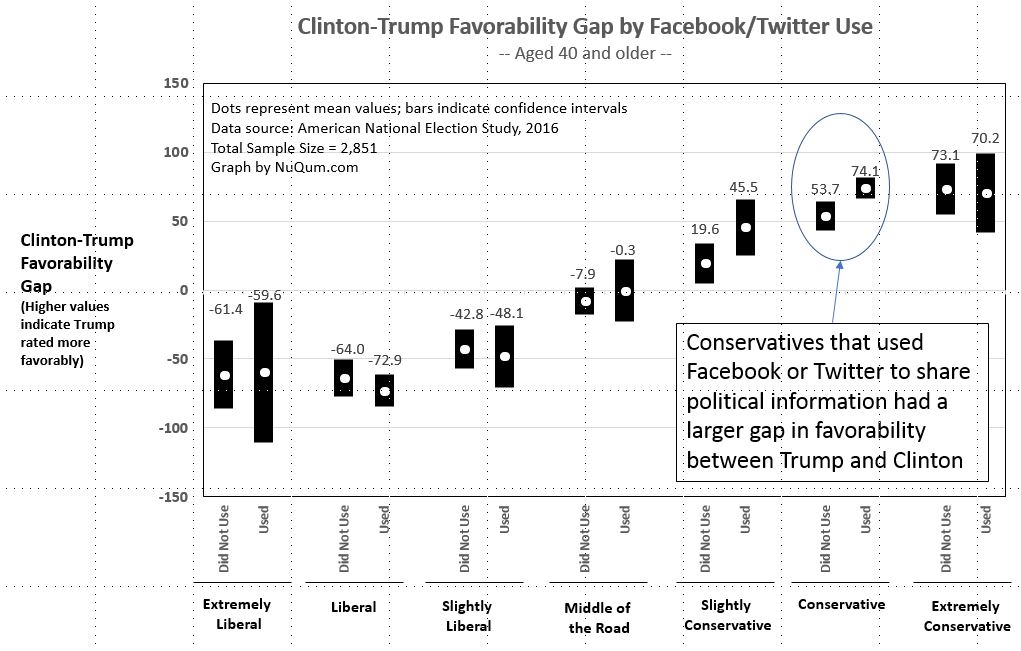

When we looked at the relative difference in favorability towards Clinton and Trump (see Figure 5 below), the same older conservatives appeared to stand out. “Conservatives” (aged 40 or older) that used Facebook and Twitter to share political information were significantly more positive towards Trump, relative to Clinton, than those in the same demographic category but did not use Facebook or Twitter for political information sharing.

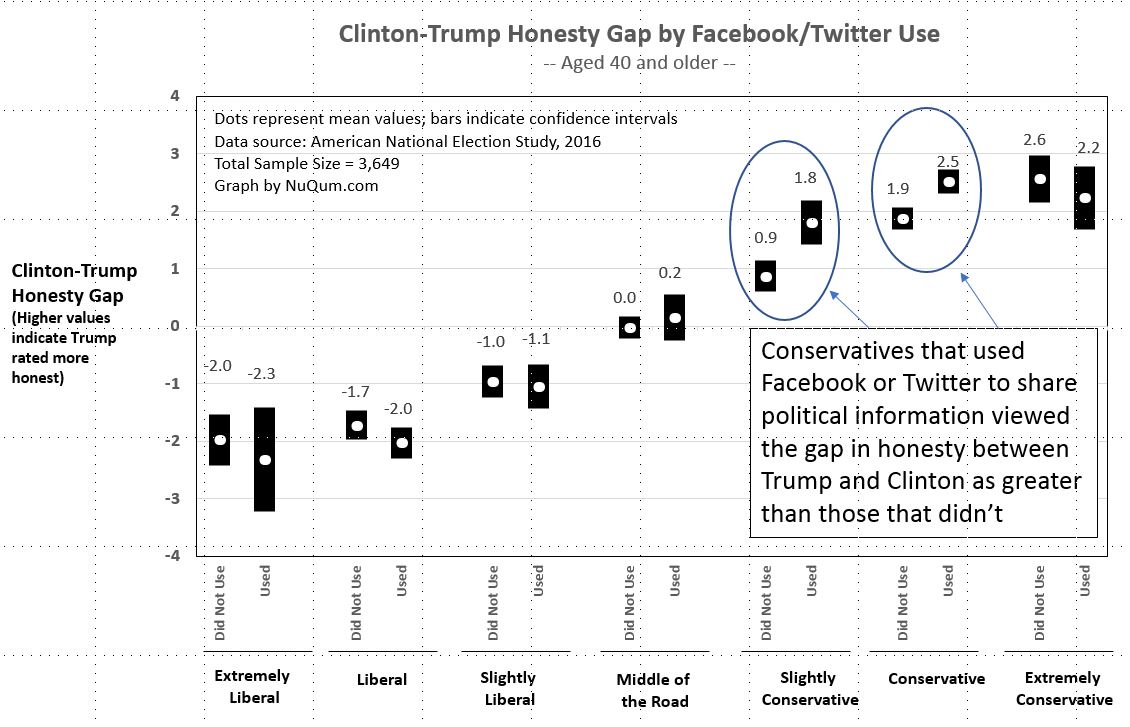

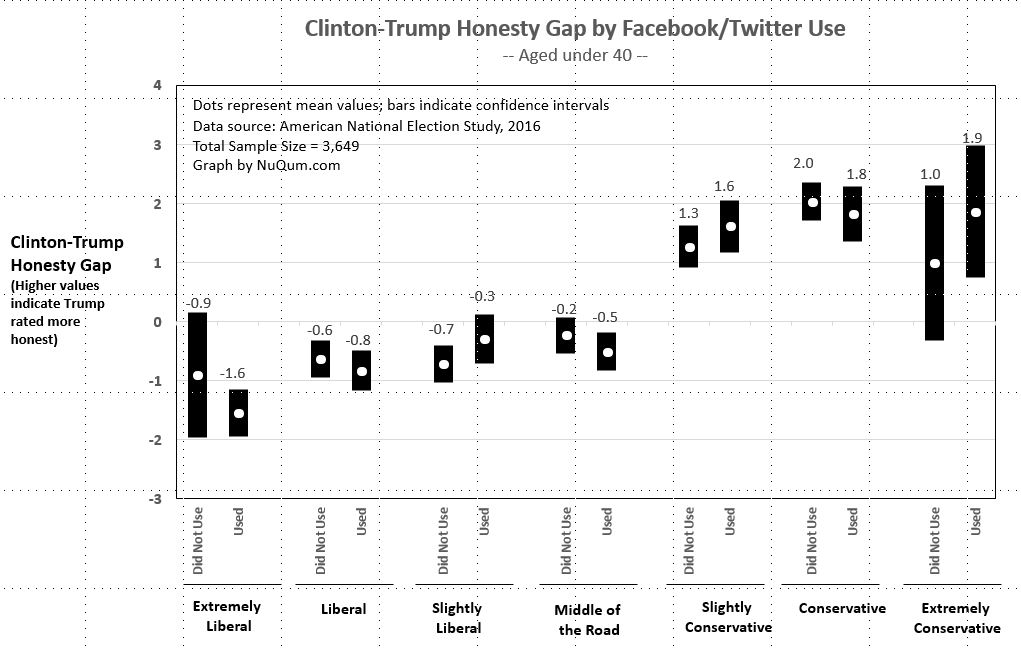

When assessing the honesty of the two presidential candidates, “slightly conservative” and “conservative” adults (aged 40 or older) who used Facebook or Twitter for sharing political information thought Trump was much more honest than Clinton than did otherwise similar adults who had not used Facebook or Twitter for political information sharing (see Figure 6 below).

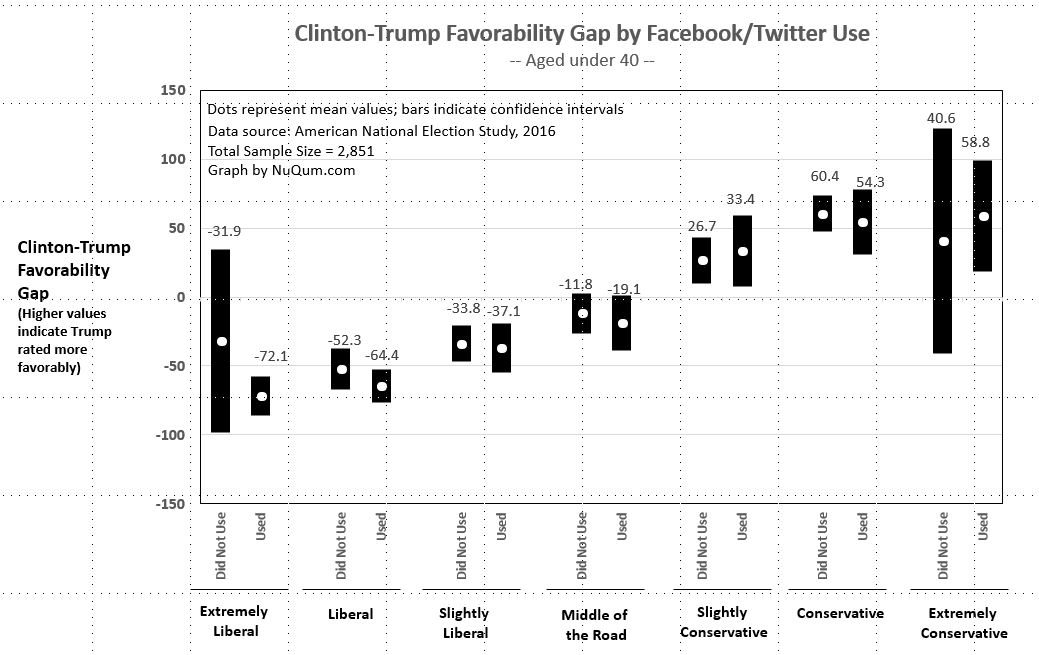

Again, this disparity in the honesty gap did not occur between Facebook/Twitter users and non-users for any other ideological or age group (see Appendix B for similar charts on those under 40 years of age).

It does appear older conservatives that used Facebook or Twitter for sharing political information experienced a different election than those that did not. More importantly, the implication is that, for conservative Americans, the election was a much more negative experience with respect to Clinton. By comparison, among liberals, use of Facebook or Twitter for sharing did not relate to their relative views about the two candidates.

As to why “extremely conservative” adults aged 40 or older didn’t show similar attitudinal disparities between Facebook/Twitter users versus non-users, it may be that once people pass a threshold in their dislike of a candidate, the heart can’t get any darker. Similarly, the lack of a social media effect on “extreme” conservatives may be that they were already exposed to so much negative information about Clinton outside of social media that anything else was redundant.

It is also puzzling that the social media effect was not significant with people that considered themselves ‘middle of the road’ ideologically, though directionally their attitudes were more negative towards Clinton if they used Facebook or Twitter for sharing.

Are these differences necessarily a function of Russian meddling?

It cannot be emphasized enough, these attitudinal differences are not necessarily a product of Russian meddling. In fact, from what we know about the differences in social media spending by the two presidential campaigns compared to the Russians, it is reasonable to question how the Russians could possibly have impacted the election.

Combined, Clinton and Trump spent $81 million on social media advertising. That is substantially more than the $1.5 million spent per month by the Internet Research Agency (IRA) in the year or two prior to Election Day, as detailed in the indictment of 13 Russians by the Robert Mueller -led investigation.

However, $1.5 million per month isn’t just pissing in the wind either. And through IRA’s use of Twitterbots and other impression-seeding and multiplier techniques, that $1.5 million per month may well have had a much bigger impact than the reported monthly spending figure indicates.

And while we want to think social media have become decisive in national elections, the campaign ecosystem is too massive and interdependent to assign that much power to Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

A comprehensive media study of the 2016 election by Rob Faris, Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman and Yochai Benkler shows that the media’s “coverage of Trump overwhelmingly outperformed coverage of Clinton.” Where Clinton’s coverage was focused on scandals, Trump’s was focused on his core issues (immigration, trade and jobs). To what extent Russian trolls contributed to that phenomenon is difficult (if not impossible) to assess using their data (..but we are trying as you read this). You can access their data here.

So, we are extremely cautious about reading too much into some attitudinal differences within a small segment of the vote eligible population (25 percent, approximately). It is too soon to assign differences to Russian meddling.

Yet, the attitudinal differences we are seeing in the 2016 ANES related to social media use are proving to be robust. Though not included in this article, in trying to explain candidate favorability ratings and assessments of their honesty, we ran numerous linear regression models controlling for factors such as age, ideology, sex, education, interest in politics, race, and Hispanic heritage. And, across the various models, the impact of social media use (Facebook/Twitter) among older conservatives never lost statistical significance.

We believe something unique in the social media sphere happened among older conservatives affecting their views of Hillary Clinton.

But we remain skeptical of our own results. And there are three additional reasons why we are so skeptical:

First, social media is already so partisan and negative that it didn’t require the Russians to make it worse. Facebook and Twitter are already virtual cesspools of hate, negativity, distrust, and unhinged hostility. Those platforms didn’t need the Russians’ help to make them repositories of society’s lowest forms of political dialogue.

Besides, the Russian meme’s were often more absurdist than negative, and sometimes even funny. We highly recommend, if you haven’t visited already, an anonymously authored blog on Medium.com that is warehousing the Russian 2016 election memes.

Given the already negative nature of social media, the attitudinal differences seen in the 2016 ANES are likely due more to the overall nature of social media than anything the Russians did. But we have seen no evidence to help us decide what was the cause of these differences.

Second, to determine the effect of Russian meddling on attitudes, we would need to know what respondents actually saw on Facebook or Twitter, including both the Russian-sourced content and other content. The 2016 ANES tells us about sources and channels of communication used during the election, but tells us little about the specific content. Without that information, it is impossible to definitely conclude the “Russians caused it.”

And, third, there is the problem of self-selection. Perhaps older conservatives that use Facebook or Twitter for sharing political information are distinguishable from otherwise similar adults on a factor that was not measured. And if that factor correlates with political attitudes and opinions, we could see the same results shown in Figures 1 and 2 without being the result of the Russians.

Next steps and final thoughts

The relevant questions to vote eligible Americans about the 2016 presidential election and the Russian-sourced social media effort are simple:

- What did the eligible voter see on social media during the campaign and when did he/she see it?

- What Russian-sourced content did he/she see on social media and when did he/she see it?

- Did his/her candidate evaluations change over the course of the campaign and, if so, when did the evaluations change?

- Did changes in his/her candidate evaluations relate to his/her social media exposure?

Simple to ask, but hard to answer.

A comprehensive media study of the 2016 election by Rob Faris, Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman and Yochai Benkler shows that the media’s “coverage of Trump overwhelmingly outperformed coverage of Clinton.” Where Clinton’s coverage was focused on scandals, Trump’s was focused on his core issues (immigration, trade and jobs). To what extent Russian trolls contributed to that phenomenon is difficult (if not impossible) to assess using their data (..but we are trying as you read this). You can access their data here.

So, we are extremely cautious about reading too much into some attitudinal differences within a small segment of the vote eligible population (25 percent, approximately). It is too soon to assign these differences to Russian meddling.

Yet, the attitudinal differences among older conservatives are proving to be robust across our analyses of the 2016 ANES. Though not included in this article, in trying to explain candidate favorability ratings and assessments of their honesty, we ran numerous linear regression models controlling for factors such as age, partisanship, ideology, sex, education, interest in politics, race, and Hispanic heritage. And, across the various models, the impact of social media use (Facebook/Twitter) among older conservatives never lost statistical significance.

Is it the Russians? Not too long ago we would have said, emphatically, no way. Now we are not so sure.

We believe these attitudinal differences within older conservative Americans warrant closer examination if we are ever to find how Russian meddling affected the 2016 election.

The 2016 USC Dornsife / LA Times Presidential Election Poll and the RAND 2016 Presidential Election Panel Survey (PEPS), both of which implemented panel designs to allow for assessing the impact of specific events and media exposures during the campaign, may offer an opportunity to merge Facebook, Twitter and Instagram behaviors to specific individuals in their surveys. If so, those two research instruments may represent the best (and only) chance we have to answer the question, “Did the Russians affect our presidential election result in 2016?”

As of today, we believe the Russians did target older conservatives who were more vulnerable to their anti-Clinton memes and messages. The result is that these conservatives became significantly more negative towards Hillary Clinton than they would have been otherwise without Russian meddling.

Appendix A – Methodology

The 2016 American National Elections (Time-Series) Study is sponsored and managed by the University of Michigan and Stanford University.

The national survey is designed to assess electoral participation, voting behavior, and public opinion as it relates to eligible U.S. voters. In addition to the political content of the survey, it also measures media exposure, cognitive style, and personal values.

Data collection for the ANES 2016 Time Series Study began in early September and was completed in January, 2017. Pre-election interviews were conducted with study respondents during the two months prior to the 2016 elections and were followed by post-election re-interviewing beginning November 9, 2016. Both face-to-face interviewing and Internet-based data collection was conducted independently, using separate samples but substantially identical questionnaires. Web-administered cases constituted a representative sample separate from the face-to-face.

The SPSS dataset we used for our analysis combined the face-to-face and Internet samples which can be summarized as follows:

Analytic survey weights, provided by the ANES researchers, were used in all of the quantitative analyses presented in this article.

A complete description of the ANES 2016, including datasets, questionnaires, and supporting documentation, can be found here.

Appendix B – Other Tables and Figures

{Send comments to: kkroeger@nuqum.com}

About the author: Kent Kroeger is a writer and statistical consultant with over 30 -years experience measuring and analyzing public opinion for public and private sector clients. He also spent ten years working for the U.S. Department of Defense’s Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness and the Defense Intelligence Agency. He holds a B.S. degree in Journalism/Political Science from The University of Iowa, and an M.A. in Quantitative Methods from Columbia University (New York, NY). He lives in Ewing, New Jersey with his wife and son.