By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; May 20, 2019)

Defense of the left flank has been pivotal in U.S. history.

Perhaps no example more important than during the Battle at Gettysburg when General Lee’s Confederate Army attacked the Army of the Potomac’s lightly-defended left flank, commanded by Major General George Meade, at Little Round Top on July 2, 1863.

Had the Confederates captured Little Round Top, Confederate cannon fire likely would have broken the Union lines and led to their defeat at Gettysburg, allowing Lee’s Confederate forces to march on towards Washington, D.C. and possible victory in the Civil War.

Had that happened, our country would probably be very different today.

As it is, some otherwise reasonable people are arguing, including Donald Trump’s former lawyer, Michael Cohen, that President Trump would start a Second Civil War, if he had to, just to stay in office.

“In years past, Americans have trusted our system of government enough that we abide by its outcomes even though we may disagree with them. Only once in our history — in 1861 — did enough of us distrust the system so much we succumbed to civil war,” writes former Secretary of Labor under Bill Clinton, Robert Reich. “But what happens if an incumbent president (Trump) claims our system is no longer trustworthy?”

Such speculation is careless hyperbole, but does demonstrate how critical many Democrats view the upcoming 2020 presidential election and why they might want to pay more attention to their left-flank problem.

How big could a left-flank collapse become within the Democratic Party?

The Democratic Party’s left flank is not as big as progressives want to believe, either is it as small as establishment Democrats want to admit. Using the 2018 American National Election Study’s (ANES) survey of 2,500 vote eligible Americans, in previous essays to I tried ascertain the size of the Democrats’ most progressive wing. Whether using self-described ideology measures or a summary of public policy attitudes, my conclusion has generally been that approximately 25 percent of the Democratic Party is a left-flank progressive.

Its not large enough to take control the Democratic Party, but large enough to tilt the balance in a close presidential election — which is the focus of this essay: If the Democrats nominate former Vice President Joe Biden, how many left-flank progressives could potentially defect from their party’s 2020 presidential nominee?

The answer might not satisfy either ideological side of the Democratic Party.

Data and Methods

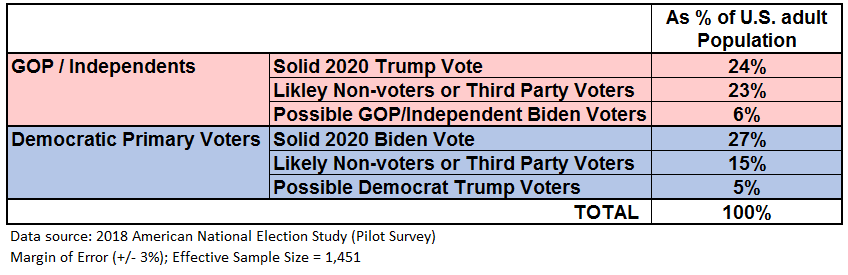

To assess the potential scale of a left-flank collapse within the Democratic Party, I looked at the self-reported votes and vote intentions of all 2,500 ANES respondents (an effective sample size of 1,451 respondents when survey design effects are considered).

As a first step, I divided the respondents into two groups: (1) Those intending to vote in the 2020 Democratic primaries (48% of the voting eligible population [VEP]), and (2) those respondents that are not (52% of VEP). Not surprisingly, most in the first group are self-reported Democrats (80%) and the remaining are evenly split between Republicans and independents. Likewise, 61 percent in the second group are Republicans, followed by independents (26%) and Democrats (13%).

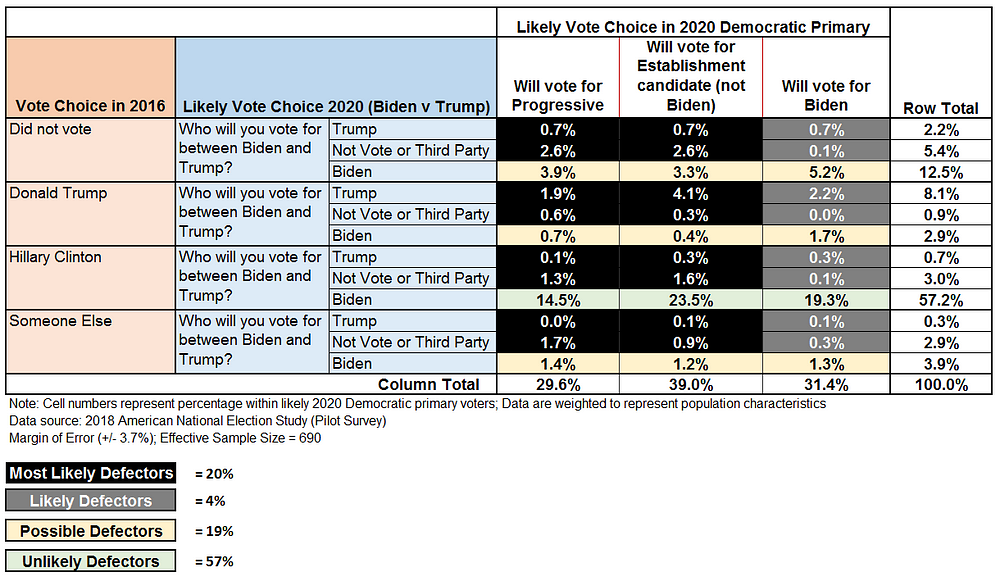

Respondents intending to vote in the 2020 Democratic primaries were asked their vote preference at the time of the ANES survey (December 2018), along with their 2016 vote choice and their preference between Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden in 2020.

Figure 1 shows the cell percentages within likely 2020 Democratic primary voters crossed by their 2016 vote choice (Clinton, Trump, Someone Else, or Not Voting) and their likely choice in 2020 (Biden, Trump, or Third Party/Not Voting). Respondents indicating they would vote for either Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren in the primary were labeled ‘progressive’ Democratic primary voters, and those indicating they would vote for Biden, Kamala Harris, Beto O’Rourke, Cory Booker, Kirsten Gillibrand, or Amy Klobuchar, were labeled ‘establishment’ voters.

Figure 1: Vote Choice in 2016 and Vote Intentions (as % of Likely 2020 Democratic Primary Voters).

From this crosstabulation, respondents were classified into one of four ‘Democrat Party defector’ categories: (1) Most Likely Defectors, (2) Likely Defectors, (3) Possible Defectors, and (4) Unlikely Defectors.

Democratic Party Defector Definitions:

The Results

Of primary interest in this essay are the Most Likely Defectors — who are the group most likely to either vote for a third party candidate or not vote at all. They account for 20 percent of likely Democratic primary voters and are evenly split between ‘progressive’ Democratic voters and ‘establishment’ (but not Biden) voters. Likely Defectors are a mere 4 percent, while Possible Defectors make up 19 percent of likely Democratic primary voters. By far, Unlikely Defectors are the largest category, representing 57 percent of likely Democratic primary voters.

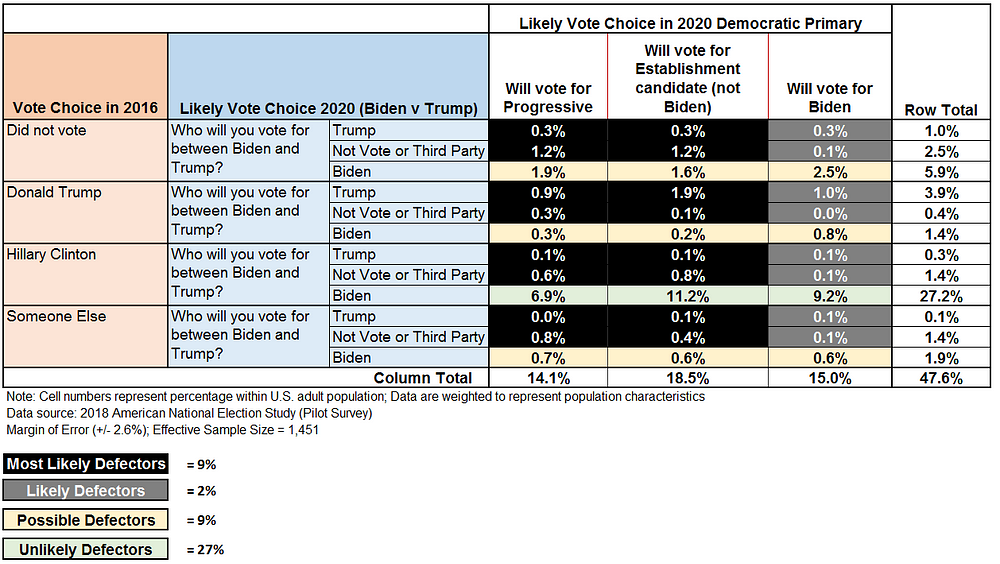

More instructive is to look at those proportions relative to the VEP. In Figure 2, we see that Most Likely Defectors make up 9 percent of the VEP, of which 4.2 percent are progressives — representing a voter group larger than the popular vote gap between the two major-party candidates in four of the past six presidential elections. And that does not factor in the Possible Defectorsthat could add as much as 2.2 percent of the VEP to that voter group.

Given that Hillary Clinton won the 2016 popular vote with only 27 percent of the VEP (compared to 26 percent for Trump), the possibility of Biden losing even half of the Most Likely Defectors in the Democratic Party’s left flank is potentially decisive.

Figure 2: Vote Choice in 2016 and Vote Intentions (as % of Vote Eligible Population).

The Democratic Party’s vulnerability to a collapse of its left flank is far from certain should Biden become the party’s nominee. It is equally probable that the establishment-preferring right flank — equal in size to the left flank — will defect. The 2020 outcome very likely could come down to how well Biden (or any Democratic nominee) balances the policy demands of the left flank (e.g., Medicare-for-All, the Green New Deal, etc.) and the centrist policy preferences of the party’s right flank. Going too far in either direction could be the biggest mistake the party nominee makes.

It’s a balancing act Joe Biden has never accomplished as a presidential candidate.

Barack Obama was able to paper over many of those fundamental party differences with his charisma and barrier-breaking candidacy. It is hard to see how Biden can recapture that level of political energy.

However, thanks to Trump’s comparatively low approval ratings and apparent inability (or desire) to expand his support base, Biden may not need Obama’s magnetism. He only needs the support of more than 26 percent of the vote eligible population which appears to be the maximum Trump can expect.

To be clear, the Republicans have a much bigger electoral coalition problem at the presidential level than do the Democrats — which I examined in a previous essay.

Nonetheless, Biden potentially losing support from four percent of the vote eligible population due to a left-flank rebellion is unacceptable and, based on the 2018 ANES, not at all impossible.

- K.R.K.

Data and SPSS code available upon request to: kroeger98@yahoo.com

Appendix: Notes on Expected 2020 Presidential Voter Turnout

Vote choice represents roughly half of the prediction equation. Also important is the decision whether to vote at all, or to vote for a third party (which is equivalent to not voting from the perspective of the two major-party candidates).

Therefore, for methodological simplification, I’ve combined non-voting with third-party voting in this essay.

The 2016 presidential election had a 55.7 percent voter turnout, with 94.3 percent of the vote going to either Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump, the remaining vote going to other candidates. Adjusted to represent only Clinton or Trump voters (the two-party vote), the 2016 presidential election had a voter turnout of 52.5 percent. The average two-party presidential vote turnout since 1996 has been 51.9 percent.

Based respondents’ self-reported intentions in the 2018 ANES, the two-party voter turnout in 2020 will be around 62 percent of the VEP (see Figure A1). That would exceed by a significant margin the 57 percent two-party voter turnout in the 2008 election. While self-reported behaviors in opinion surveys are often inflated, the 2018 ANES results may be foreshadowing an unusually large voter turnout in 2020.

Figure A1: Expected Two-Party Vote in 2020 based on 2018 ANES