By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, August 7, 2020)

As he sat before the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis on July 31st, Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), was asked about Europe’s success in controlling the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) and the possible need for a national-level mandate on mitigation and suppression policies (M&S) in the U.S. His response illustrates the problem in relying solely on scientists to make sound public policy.

“They (Europe) shut down about 95 plus percent of their (economy)…we (the U.S.) shut down only about 50 percent. As a result, Europe came down to a low baseline (for new daily infections), while we plateaued at about 20,000 cases-a-day at the time that we tried to open up the country–and when we opened up the country we saw–particularly in the southern states–an increase of cases up to 70,000 per day.”

The implication Dr. Fauci was making–and what the Democratic committee member were eagerly poised to jump on–was that the U.S. should have shut down 95 percent (plus) of its economy, as Europe did, and that we may still need to do so.

It is somewhat trivial to say that strict lockdown policies can stem the spread of a highly contagious virus like SARS-CoV-2 (“the coronavirus”). At its extreme–say, lock everyone in a hermetically-sealed canister that can provide them food and water for an extended period of time–and, of course, the virus will not spread.

On a more practical level, worldwide seasonal flu data has demonstrated that Christmas and Holiday school closures reduce the spread of the seasonal flu, and there is little scientific controversy over this phenomenon and its causal reasons: Kids are filthy flu magnets.

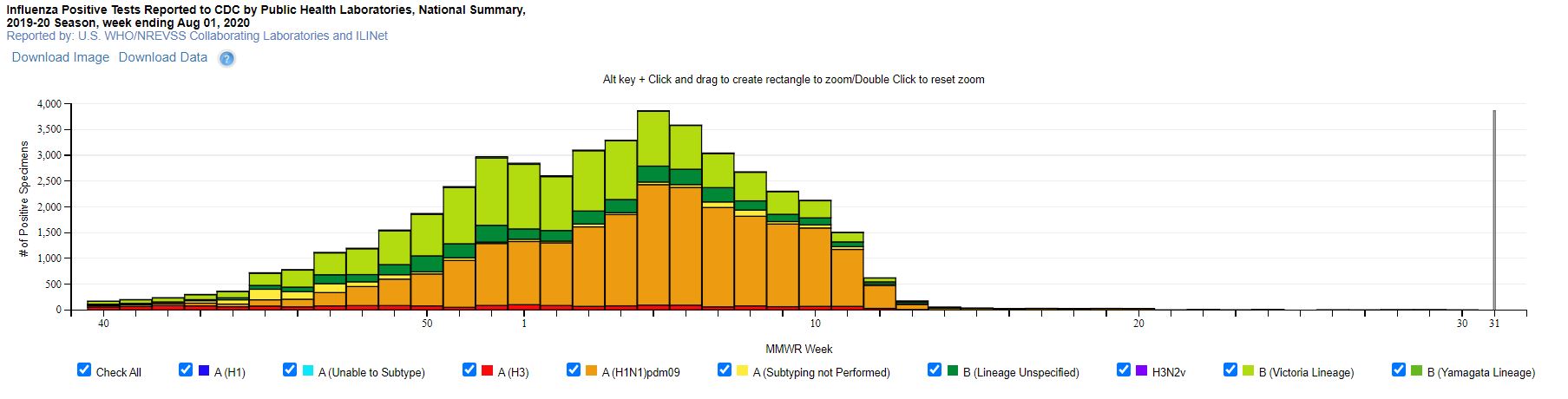

The weekly 2019-20 seasonal flu cases reported by public health laboratories shows this ‘school closure’ dip in the first two weeks of 2020.

Figure 1: Positive Flu Tests in US. Reported to CDC by Public Health Labs from Sept. 2019 to Aug 2020 (Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC))

Few Republicans are arguing that lockdowns (including school closures) don’t achieve their desired goal of reducing viral transmissions. Of course they do.

Instead, the bigger question from the Republicans has always been: By implementing broad (statewide) shut downs, are we doing more damage to the U.S. economy (and the educational advancement of our students) than warranted given that the coronavirus has an CDC-estimated infection mortality rate of around 0.65 percent (or 6.5 times more lethal than the seasonal flu)?

Dr. Fauci, like many epidemiologists weighing in on the “science” of the coronavirus, doesn’t offer a substantive analysis of the trade-off between M&S policies and their economic consequences. And, frankly, its neither his job or expertise to do so.

That is why we elect representatives to go to our state legislatures and Congress to hammer out answers (under advisement from many disciplines) to these difficult questions.

Yes, science is real. But, science is not enough.

Science is not enough in making policies on climate change and it is not enough in making policies on the coronavirus.

Yes, Europe stopped the dangerous spread of the coronavirus through relatively draconian (and I believe necessary) lock down policies. In early March, who really knew how dangerous this virus really is? But what has been the economic damage and how does it compare to the clear benefits of reducing the spread of this virus?

As Europe relaxes its lockdown policies, it is already seeing a renewed rise in daily coronavirus cases–though not to the extent as witnessed in the U.S. since May.

Should Europe return to their prior, severe restrictions? And, if so, for how long? And does your answer to these questions assume the world will have an effective vaccine in the near future?

Though President Donald Trump continues to wax optimistic about a coronavirus vaccine being widely available soon, many epidemiologists are not as sanguine–not because they don’t like Trump–but because the history of vaccines, including effective ones, are peppered with significant setbacks and deficiencies.

According to a February CDC report, the current influenza vaccine has been 45 percent effective overall against the 2019-2020 seasonal influenza A and B viruses. And that is against viral agents–the seasonal flu varieties–where scientists have many decades of intimate experience.

“There’s no silver bullet at the moment and there might never be,” World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus warned earlier this month.

If European and U.S. politicians think their economies can withstand further broad lockdowns until the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is waiting at their local CVS Pharmacy, they aren’t too concerned with the economic well-being of their average constituent.

Neither the Democrats or Republicans are on any particular high ground in this debate. Both sides have legitimate concerns (though embarrassing Trump is not one of them), but like any tug-of-war match, at some point an empirical reality will give the advantage to one side over the other.

The latest worldwide coronavirus data says ‘culture matters.’

Serious research is already weighing in on the effectiveness and importance of lockdown policies and other M&S strategies in controlling the coronavirus. For example, whether due to untimely gubernatorial decisions or bad luck–or both–Connecticut, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island suffered a catastrophic number of coronavirus deaths in March and April. Would they have suffered fewer cases and deaths had they shut down sooner? Columbia University researchers offer an emphatic “Yes!”

However, we are nowhere close to definitive answers to the policy questions surrounding the coronavirus–particularly since this pandemic is far from over.

Hence, I do not have the answers to the questions posed above. But, as a statistician with some minor training in epidemiology, I do feel somewhat equipped to draw impressions from the cross-national coronavirus data publicly available on websites such as those maintained by OurWorldInData.org, Johns Hopkins University and RealClearPolitics.com.

From what I see in the worldwide coronavirus fatality data up to now (i.e., deaths per 1 million people) and a recent index of national coronavirus policies (where 100 = strictest and 0 = None), the saddest cases are indisputable:

(Country — Deaths per 1M — Policy Response Index)

Belgium — 863.3 — 61

United Kingdom — 699.5 — 60

Peru — 638.5 — 78

Spain — 610.0 — 60

Italy — 582.3 — 70

Sweden — 565.9 — 35

Chile — 528.0 — 68

U.S. — 498.5 — 62

Brazil — 471.9 — 67

France — 452.5 — 65

Note: Average Policy Response Index across 145 countries = 64 (ranging between 94 in Libya to 12 in Belarus)

And the success stories are equally evident:

(Country — Deaths per 1M — Policy Response Index)

Taiwan — 0.3 — 29

Iceland — 2.1 — 43

Malaysia — 4.0 — 59

Tunisia — 4.4 — 54

New Zealand — 4.5 — 50

Georgia — 4.6 — 75

Singapore — 4.8 — 66

Slovakia — 5.7 — 56

South Korea — 5.9 — 58

Hong Kong — 6.2 — 64

While the above data does not address the timing of policy responses, it does not offer initial compelling evidence that strict coronavirus M&S policies can alone stem the spread and deadliness of the virus.

The relationship between strict M&S policies and the (population-based) mortality rate of the coronavirus is too complicated to be revealed in a simple bivariate correlational analysis.

Unfortunately, even in a more sophisticated multiple variable analysis, the relationship is more nuanced that can be easily summarized in a 3-minute network news segment.

The Data

I analyzed 108 countries using data from OurWorldInData.org, Johns Hopkins University and RealClearPolitics.com. The data is current through August 3rd for the coronavirus policy data (OurWorldInData.org) and through August 5th for the coronavirus case and fatality data (RealClearPolitics.com). Due to issues with its data reporting, I have excluded China from this analysis. Its inclusion, however, would not have changed the substance of the results reported below.

The variables used in this analysis are as follows (The above variables have hyperlinks to their original data sources):

Coronavirus Deaths per 1M People, Natural Log (LN_D) — outcome variable

Coronavirus Cases per 1M People, Natural Log (LN_C) — this is the mediating variable

Coronavirus Tests per 1M People, Natural Log (LN_T) — predictor variable

Population Density per Sq. Mile, Natural Log (LN_P) — predictor variable

Flu Deaths per 1M People, Natural Log (LN_F) — proxy for quality of health care system

Days Since First Coronavirus Case (DAY) — predictor variable

Avg. Daily Policy Response Index Since 1st Coronavirus Case (AVG) — predictor variable

Indicator Variable for Sinic countries (SIN) — predictor variable

The last two variables deserve some elaboration. The average daily policy response index is derived from an index created by Oxford University researchers (Coronavirus Government Response Tracker) and is averaged on a daily basis over the number of days since a country’s first coronavirus case. Here is a more detailed description of this variable found on OurWorldInData.org:

The research we provide on policy responses is sourced from the Oxford Coronavirus Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT). This resource is published by researchers at the Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford: Thomas Hale, Anna Petherik, Beatriz Kira, Noam Angrist, Toby Phillips and Samuel Webster.

The tracker presents data collected from public sources by a team of over one hundred Oxford University students and staff from every part of the world.

OxCGRT collects publicly available information on 17 indicators of government responses, spanning containment and closure policies (such as such as school closures and restrictions in movement); economic policies; and health system policies (such as testing regimes). Further details on how these metrics are measured and collected is available in the project’s working paper.

The other variable–an indicator for Sinic countries–is taken from work by American Sinologist and historian Edwin O. Reischauer, who grouped China, Korea, and Japan into a cultural sphere that he called the Sinic world. He categorized these countries based on their state centralization and shared Confucian ethical philosophy. This is a blunt measure of a nation’s culture: Is the country a centralized Confucian society or not?

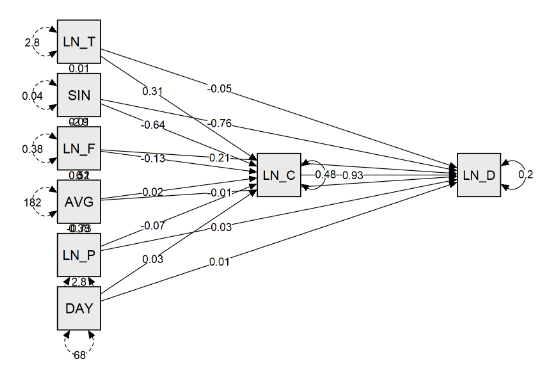

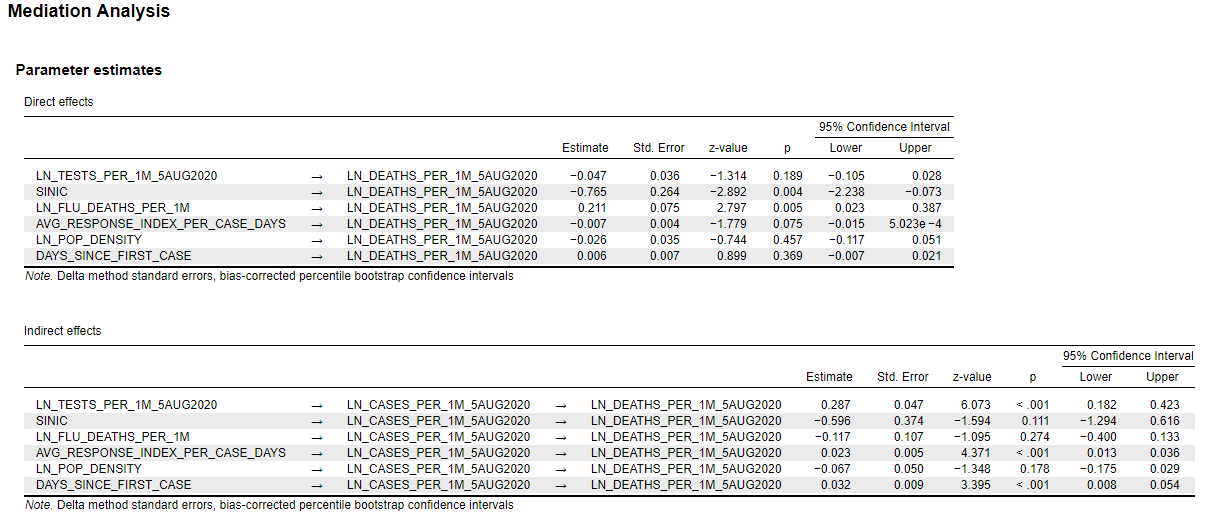

Finally, in order to account for the indirect and direct effects of each variable on the outcome variable (deaths per 1 million people), I employed a mediation analysis using JASP software. The parameter estimates for the complete model are in the appendix below and are available in more detail by request to: kroeger98@yahoo.com.

The Results

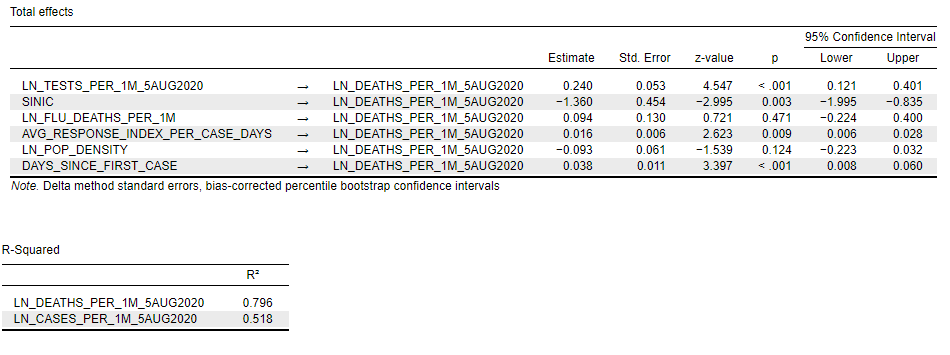

The path model and the parameter estimates for the total effects of each variable on the number of Deaths per 1 Million People (outcome variable) are seen in Figure 2. This table does not include the mediator variable–Cases per 1 Million People–whose effect on the outcome variable is seen in the path diagram and reported in the appendix below.

Figure 2: The Total Effects of Each Predictor Variable on Deaths per 1M People

PATH MODEL:

[Specific interpretations of the parameter estimates are left up to the reader. To learn more about how to interpret parameter estimates in a mediation analysis, I recommend the following resource: University of Virginia Research Data Services]

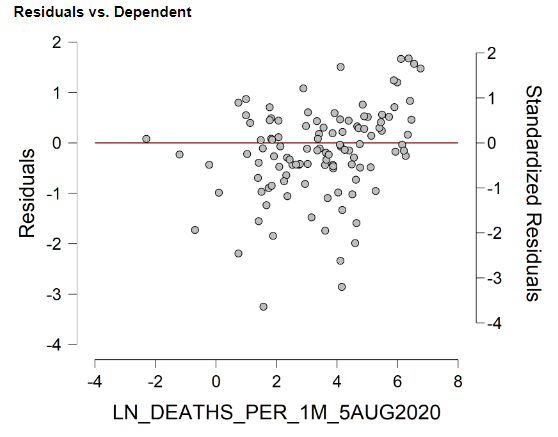

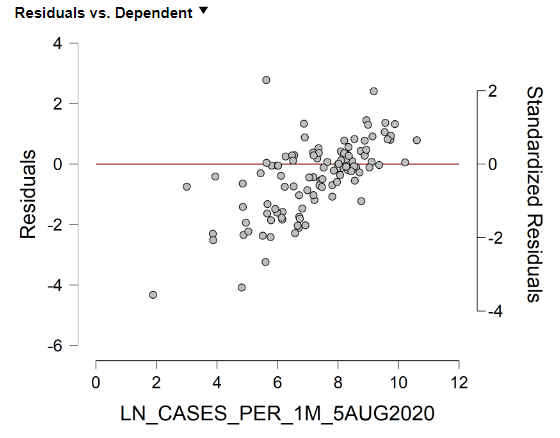

Note first that the models for Deaths per 1 Million People and Cases per 1 Million People have decent fits (R-squared = 0.80 and 0.52, respectively). Also, the errors in both models do not significantly deviate from random noise (see appendix).

More interestingly, only four of the predictor variables are found to have a significant total effect on the number of Deaths per 1 Million People. I will discuss each briefly:

The number of Tests per 1 Million People is the most powerful predictor of the number of Deaths per 1 Million People and the relationship is positive: More tests per capita corresponds to more deaths per capita, all else equal. That does not mean a country can reduce its coronavirus deaths by conducting fewer tests(!). It does mean that countries with relatively more coronavirus deaths also have conducted relatively more tests, even after controlling for the effect of the number of Cases per 1 Million People. In my view, the relative number of tests is a proxy variable for the level of effort a country is putting into understanding and controlling the coronavirus.

The second most significant predictor of coronavirus Deaths per 1 Million People is the number of Days Since 1st Reported Coronavirus Case. In other words, all else equal, the longer the virus has been in the country, the higher the relative number of deaths per capita. Not at all surprising.

The third most significant predictor of coronavirus Deaths per 1 Million People is whether or not a country is a Sinic country. All else equal, highly centralized and Confucian-based societies (i.e., South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong) have a significantly lower number of deaths per capita.

Culture matters when it comes to controlling the spread of the coronavirus. It matters a lot. As it has been put to me many times from multiple sources, people in East Asia (and Russia) know how to be sick.

Finally, the real conundrum of this analysis. The coronavirus policy index variable is a significant predictor of the number of coronavirus deaths per capita, but in the positive direction(!). In other words, all else equal, countries with the strictest coronavirus M&S policies have a higher number of coronavirus deaths per capita.

But relax. The interpretation of this result is critical. The best interpretation, in my opinion, is that strict coronavirus M&S policies are a response by countries that have faced the worst invasion of this virus (up to now)–Italy, Spain, U.S., and Belgium, etc.–with Sweden a notable exception. In Sweden’s case, the country did not have particularly draconian reaction to the pandemic and–as of August 5th–has not suffered any more or less than a large number of countries that with a relatively large number of deaths per capita despite implementing strict M&S policy measures.

These conclusions are obviously far from definitive. And, keep in mind, I have done nothing here to consider the economic consequences of a particular M&S policy.

These conclusions are obviously far from definitive. Further data collection and analyses are required that account for the bidirectional causality of these relationships (such as coronavirus policies being a response of the relative number of deaths) and that model the causal dynamics in a time-series context (e.g, changes in X at time 0 cause changes in Y at time 1).

As the policy science on the coronavirus pandemic stands today, any declarative statements made by politicians, scientists, or the news media about the effectiveness of some M&S policies — such as economic lockdowns — must be considered in concert with the potential political or partisan biases of the statement’s source. The actual evidence supporting the many M&S policy options — -”the science” as they say — is far too complex and nuanced to be handled as simplistically as it usually is in the national media.

The coronavirus pandemic has become a political football, used primarily as a cudgel against the current U.S. administration. When this pandemic is over, the most interesting analytic question–which I have no doubt nobody in U.S. academia will touch–is how many deaths were caused by the politicization of the coronavirus pandemic.

In the past I have said that hyper-partisanship is deadly to our democracy. I didn’t mean it literally then, but I might now.

Final Thoughts

Despite the panic porn that describes most of the national media’s coverage of the coronavirus pandemic, I do believe the policy answers we crave are already out there.

The World Health Organization Director-General Tedros gives perhaps the soundest policy advice, given the known science:

“Testing, isolating and treating patients, and tracing and quarantining their contacts. Do it all.

“Inform, empower and listen to communities. Do it all.

“For individuals, it’s about keeping physical distance, wearing a mask, cleaning hands regularly and coughing safely away from others. Do it all.

“The message to people and governments is clear: Do it all.”

On a fundamental level, Dr. Tedros is talking about changing world culture so it can better handle highly contagious and deadly viruses like SARS-CoV-2. As the analysis here suggests, the Sinic countries may be farther along in that regard.

Dr. Tedros’ advice is also in stark contrast to Dr. Fauci, the Democrats and the anti-Trump mob, as he does not mention the further shutting down of the world economy for indefinite amounts of time in the hope that a vaccine is just around the corner.

He knows better. The world can’t afford to be that wrong.

- K.R.K.

Comments can be sent to: kroeger98@yahoo.com

or tweet me at: @KRobertKroeger1

APPENDIX: