By Kent R. Kroeger (May 2, 2018)

A delusive debate has erupted in Washington, D.C., driven mostly by narrow partisan agendas, with little attention to the real issues involved. In the process, the Trump administration has put congressional Democrats in the position of defending government secrecy and privilege at the expense of the public’s right to know how its government operates.

This newest partisan conflict concerns a proposed policy at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) that will change how the agency assesses and uses scientific research during the regulatory and rule-making process.

Though this new policy has not been formally written, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt announced in an April interview with the Daily Caller a potential policy that would prohibit the EPA from using scientific research unless its resultant data are released publicly for independent scientists and industry experts to review.

Pruitt’s policy proposal would change a long-standing EPA policy allowing regulators to depend on non-public scientific data in developing environmental rules and regulations.

“We need to make sure their data and methodology are published as part of the record,” Pruitt said to The Daily Caller. “Otherwise, it’s not transparent. It’s not objectively measured, and that’s important.” According to Pruitt, ‘scientific secrecy’ increases the likelihood of bad science— and even fraud — influencing public policy.

Pruitt will reverse long-standing EPA policy allowing regulators to rely on non-public scientific data in crafting rules.

The response from Democrats and environmental advocates was swift. In their view, this policy is designed to restrict the scientific research available to the agency when it writes environmental regulations and, in cases where a study’s data are made available to the public, risks violating confidentiality agreements signed by the study’s participants.

Moreover, such transparency will give critics of EPA regulations, particularly those pertaining to the fossil fuels industry, an increased opportunity to undermine the credibility of the science underwriting those regulations.

Recalling industry resistance to the Six Cities Study (published in 1993) on the health impact of air pollution, Sean Gallagher, a government relations officer with the American Association for the Advancement of Science, said Pruitt’s new transparency policy would have prevented research like the Six Cities Study to influence environmental policy.

“They (the fossil fuels industry) didn’t like the regulation, so they tried to attack the science underlying the regulation,” Mr. Gallagher told the New York Times. “It has become very clear to us that this is not about science. This is a means to an end.”

According to Pruitt’s critics, this transparency policy would have a significant impact on environmental regulations premised on research linking pollution and other toxic hazards to individual health outcomes. Without human exposure data, many EPA regulations would never exist.

Hence, the strong belief among congressional Democrats that this is exactly the outcome Pruitt and the Trump administration want.

The New York Times editorial board summarized Pruitt’s motives as such:

“Scott Pruitt, the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, took yet another step to muzzle the scientific inquiry that for years has informed sound policy at an agency he seems determined to destroy. He told his subordinates that they could no longer make policy on the basis of studies that included data from participants who were guaranteed confidentiality.”

So who is right? Is the Pruitt transparency proposal an attempt to increase the government’s accountability to the people? Or a cynical use of privacy rights to prevent significant public health research influencing environmental policy?

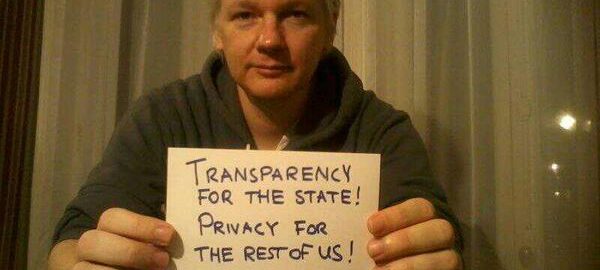

In essence, this current dispute is a battle between two equally democratic virtues: government transparency versus individual privacy rights.

With respect to EPA regulations, Pruitt’s critics assume privacy is sacrificed by increased transparency. Pruitt and the Trump administration, in contrast, believe one doesn’t compromise the other.

In this debate, Pruitt and the Trump administration are more right than their critics. Increased scientific transparency through the public release of scientific data does not have to jeopardize study participants’ privacy and, therefore, should not impact the availability of scientific data in the development of environmental policy.

I worked for five years (2002–2007) in the Defense Manpower Data Center, the U.S. Department of Defense unit responsible for implementing the release of public use datasets derived from opinion surveys of U.S. military personnel.

Our research office conducted surveys of military personnel on topics ranging from a person’s financial situation, health status, mental health issues, sexual assault and attitudes about their military service. These were highly sensitive topics and privacy was paramount in the successful collection and analysis of this type of information.

Internally, data from our surveys informed personnel policy decisions ranging from sexual assault to the DoD’s Tricare health care system. But we also had researchers external to the government using our data for evaluating the status of our nation’s civilian and military defense personnel.

In that effort, our office implemented de-identification methods on the survey data that protected the privacy of survey respondents but also allowed academic and defense policy ‘think tanks’ to access DoD survey data.

It is unlikely that the datasets informing environmental policy are more sensitive than those informing defense personnel policy.

Transparency was not compromised by privacy considerations within DoD survey research because it was never considered a zero-sum game. Both democratic virtues of transparency and privacy existed together without ever one diminishing the other.

How is that possible?

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is a measurement standards laboratory, and a non-regulatory agency within the U.S. Department of Commerce whose mission is to promote innovation and industrial competitiveness.

The Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA) of 2014 establishes NIST as responsible for developing information security standards and guidelines for federal information systems, including establishing rules and procedures for protecting Privacy Act of 1974 information.

In Dec. 2016, NIST released draft guidelines on how government agencies can prepare datasets for public release once those agencies de-identify individuals within the datasets without compromising their scientific value while also protecting individuals’ private information.

According to NIST, “De-identification is not a single technique, but a collection of approaches, algorithms, and tools that can be applied to different kinds of data with differing levels of effectiveness. In general, the potential risk to privacy posed by a dataset’s release decreases as more aggressive de-identification techniques are employed, but data quality decreases as well.”

Data scientists have established procedures by which identifying information in a dataset can be protected using indirect identifiers, such as the commonly used k-anonymity model. Furthermore, a wide range of software tools are already developed to implement various de-identification procedures, including AnonTool, ARX, the Cornell Anonymization Toolkit, Open Anonymizer, Privacy Analytics Eclipse, µ-ARGUS, sdcMicro, SECRETA, and the UTD Anonymization Toolbox.

Once identifying information is removed from a government dataset, the government has a number of methods by which it can release the dataset to the public. These include:

● The Release and Forget model: The de-identified data is released to the public directly without any access restrictions.

● The Data Use Agreement (DUA) model: The de-identified data is made available only to qualified users under a legally binding data use agreement that details how the data can be used.

● The Synthetic Data with Verification Model: A synthetic dataset is created that maintains the statistical properties of the original dataset, but which does not contain private information.

● The Enclave model: The de-identified data is maintained in a segregated enclave that restricts access to the original data, and only accepts queries from pre-qualified researchers.

There is no privacy-based excuse for federal agencies to restrict the use of individual-based scientific data in the development of public policy.

Under the Obama administration, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) directed Federal agencies in 2013 to develop plans to provide for increased public access to digital scientific data. Under its guidelines, Federal agencies were charged with releasing data in a form that permits future analysis but does not threaten individual privacy.

Pruitt’s proposal for new transparency rules within EPA are entirely consistent with the OSTP directives. Does that mean Pruitt and the Trump administration won’t use this new requirement to de-legitimize research data that may contradict their political agenda? Of course that is a possibility. Pruitt’s transparency proposal may be no more than a Trojan horse designed to undermine existing and future environmental regulations.

But the challenge facing environmental scientists under Pruitt’s transparency proposal is not how to avoid public disclosure of their research data, but how to defend their findings in the political arena.

Pruitt’s transparency proposal is entirely consistent with this nation’s democratic ideals.

So, why the resistance from Democrats and environmental activists to Pruitt’s proposal?

The answer is politics. Period.

K.R.K.

Insults and ad hominems can be sent to: kroeger98@yahoo.com