By Kent R. Kroeger (NuQum.com, December 20, 2019)

________________________________________________________________

This essay documents my challenges and observations during my family’s recent travels through Oman and Jordan.

This is the fourth essay in a series. The previous essays can be found here, here and here.

________________________________________________________________

“Zach, you know what a hijab is, right?” I asked my teenage son, Zach, a few days prior to a recent family trip to Oman and Jordan.

“Yes, Dad. I do.” he responded in a reflexive, annoyed-teenager tone. “We have girls in school that wear them. I see them all the time.”

“Yes, but, especially in Oman, some will cover their entire face,” I said. “I don’t want it to…”

“Dad, I know. I’ve seen that before too,” Zach interrupted me mid-sentence.

“It will be more common.”

“Dad. Stop it. I don’t care.”

For some reason, I always find Zach’s thorough indifference about everything refreshing. I’m even a little jealous. He doesn’t waste a lot of energy worrying about the future or other people’s lives. Greta Thunberg he is not.

And after thinking about my non-conversation with Zach, I realized the problem was more mine than his.

Prior to this most recent trip, I had been to Middle Eastern countries where the burka (a common hijab in Afghanistan) or the niqaab (a usually black hijab that covers the entire face except for the eyes) were common. I found those particular versions of the hijab unsettling and I just wanted to prepare my son. Is that so wrong?

My wife, Christa, and I try to take advantage of any opportunity we can to engage our son in conversations about politics and current issues — in this case, the status of women in the Islamic world (and the world, in general). It is obviously not a subject self-absorbed, 13-year-old boys want to talk about, but it is precisely at that age where, as parents, my wife and I feel we can have the most lasting impact. [We admit we may be deceiving ourselves on that one; but, as progressive Democrats and regular-attending Unitarians, self-delusion is one of our most highly-developed skills.]

We just didn’t want our son to judge the women we’d be meeting on our trip based on their clothing attire. We believe what a person wears (and other daily practices) can only be understood through a deep knowledge of that person’s culture. In theory, we try not to use American cultural norms and values as criteria for judging other people and cultures. In other words, we are the people Rush Limbaugh started warning everyone about thirty years ago: We are practicing cultural relativists.

Poorly executed, cultural relativism in practice often comes across as condescending. Employed with the proper balance between humility and objective judgment, however, and cultural relativism opens up doors and understanding to other places on a level you can never attain when you restrict your analytic lens to the one provided by your own culture.

I tried to explain ‘cultural relativism’ to Zach and wasn’t sure if it really sank in.

“Dad, don’t worry. I won’t say or do anything to embarrass you and Mom on the trip,” was his curt reaction.

He can be charmless sometimes, but he knows how to cut to the chase.

_________________________________________________________________

I’m a political scientist and statistician by training and to me, Islam, as with any cultural attribute, is but one variable in a larger explanatory model. In the aggregate, all else equal, does it explain anything substantive in the corporeal world?

Western academics and thought leaders periodically trot out research and essays broadly condemning Islam and the Qur’an for the mistreatment of Muslim women.

One of the most provocative denunciations of Islam’s view on women has come from Mona Eltahawy, the renowned Egyptian writer and journalist who now lives in Cairo and New York. In her 2015 book, Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution, she repeatedly whomps Muslim men by referring them merely as ‘they’ as she summarizes what life was like for her living in Egypt and Saudi Arabia:

“They hate us because they need us, they fear us, they understand how much control it takes to keep us in line, to keep us good girls with our hymens intact until it’s time for them to fuck us into mothers who raise future generations of misogynists to forever fuel their patriarchy. They hate us because we are at once their temptation and their salvation from that patriarchy, which they must sooner or later realize hurts them, too. They hate us because they know that once we rid ourselves of the alliance of State and Street that works in tandem to control us, we will demand a reckoning.”

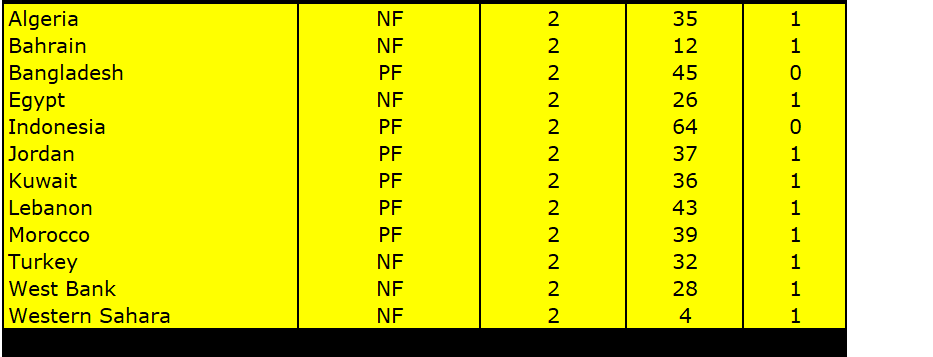

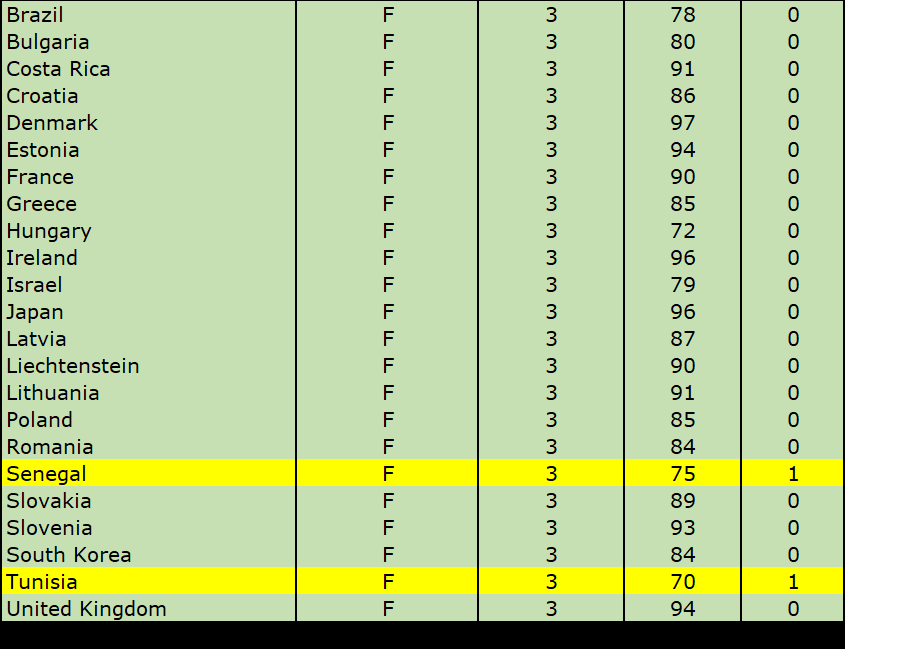

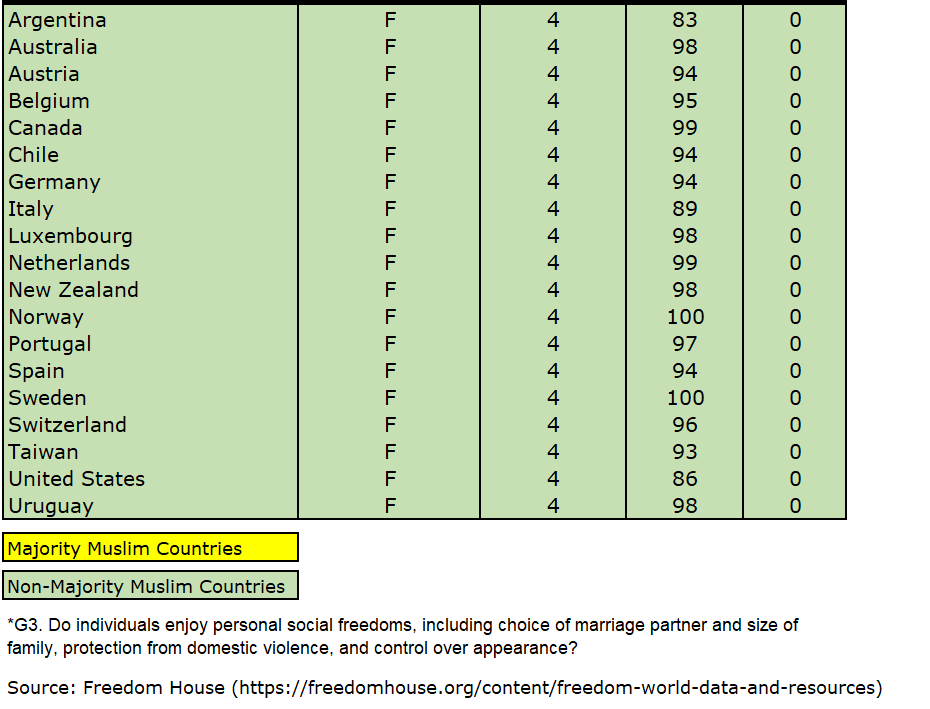

Eltahawy’s has an uncompromising view of the inveterate misogyny that is prevalent in most Muslim-majority countries today. And backing her perspective are objective data that overwhelming and unforgiving categorize Muslim-majority countries as brutal towards women (see Appendix B for the Freedom House scoring of selected countries on gender-related freedoms).

Few disagree on the problem. In most Muslim-majority countries the oppression of women is pervasive, persistent, codified and institutionalized. Gender bias runs deep in a country like Saudi Arabia where women only recently have been granted the right to drive and to travel outside the country without a male guardian’s permission.

Yet, there is significant variation in gender equality within Muslim-majority countries that should give us pause before accepting any reductive explanation ascribing the oppression of women almost solely to Islam and the Qur’an. If Muslim-majority countries like Tunisia and Senegal can be ranked similarly to the United Kingdom, Israel, Denmark and France in terms of gender-related freedoms, perhaps Islam and gender equality are compatible under the right conditions. If how Islam is practiced can adapt in some countries to the liberation of women, why not in all countries?

_________________________________________________________________

Eltahawy puts ‘headscarves’ front and center among the symbols of women’s suffering in the Islamic countries. But there is so much variation in hijab styles, it seems unnecessary to lump the overt symbolism of the burka or the niqaab — which cover a woman’s face — with the more common shayla or al-amira styles which do not cover the face.

Is the hijab really a visible sign of oppression or is it merely an article of clothing motivated by social norms, personal preferences, and/or a desire to demonstrate one’s faith?

“Sometimes a hijab is just a hijab,” a Muslim (Malaysian) friend once explained to us — a group of her graduate school colleagues — when someone suggested her hijab symbolized oppression.

At the same time, stories today of Muslim women and girls being forced to wear the hijab or enter into arranged marriages are real and include examples from Western countries. In her book, Unveiled: How Western Liberals Empower Radical Islam, Yasmine Mohamed, an author and civil rights activist, recounts her own experience growing up in Canada in a household where the rules closely resembled Sharia law and where the hijab was mandatory starting at age nine.

________________________________________________________________

While I prepared for our family trip, I reacquainted myself with the often contentious debate between religious scholar, Reza Aslan, and neuroscientist, Sam Harris, over the roles of reason (science) and religion in explaining various issues in modern society. Inevitably, their discussion miscarries into a dispute over Islam and terrorism.

Where Aslan argues Islam and its guiding text, the Qur’an, is not the cause of terrorist violence, but rather a product of long-standing social conditions and cultural norms (which can change), Harris views the Qur’an itself as a contributing factor to violence against apostates to Islam and to the oppression of women in Islamic societies. “On almost every page, the Qur’an instructs observant Muslims to despise non-believers,” HBO’s Real Time host Bill Maher once said in defending Harris.

While Harris dismisses as false equivalencies any comparisons of the Qur’an to Judeo-Christianity’s Old Testament — which is comparably soaked in violence and misogyny — more disappointing is his resistance to consider the organized violence perpetrated by Western societies against Islamic populations in distant and recent history.

Still, Harris is right when he says ‘the words matter’ and I do consider elements of his thesis as useful, particularly when considering the status of women in Islamic societies. The words we write are important. Major religions codify their rules for a reason — to maintain religious discipline and rules of engagement among their followers.

Nonetheless, my overall impulse is to side with Aslan’s multiculturalist perspective which emphasizes the central role of evolving cultural norms and social conditions in explaining current society.

The hijab is a visible manifestation of the Aslan-Harris debate. Is it the reflection of culture and, therefore, subject to change as cultural norms and rules change? Or, has the garment’s centuries-old existence through the present further evidence that the Koran’s text reinforces and preserves the oppression of women.

In a 2014 Huffington Post article by psychologist Valerie Tarico, Faisal Saeed Al Mutar, a Washington D.C.-based writer and the founder of Global Secular Humanist Movement, tells her why he rejects multiculturalism’s instinct to not judge the hijab:

“I understand the liberal impulse to respect multiculturalism, but aren’t human rights more important than cultures? Humans have rights, cultures don’t, cultures evolve and reform. Liberal friends and allies ask churches and pastors to accept gay rights and women’s rights. It is disrespectful and even racist to ask any less of mosques and Muslim leaders.”

Yet, other Muslim women say the hijab is a symbol of faith, not oppression, and resent the assumption that their personal decision to wear it is forced on them by the men in their lives.

There are no right or wrong answers here. Just a lot of opinions.

_______________________________________________________________

Like many of the world’s older cities Amman, Jordan is very walkable. Every daily need is within a short distance from where you might be standing, as self-contained neighborhoods are one of Amman’s defining features.

Leveraging this aspect of Amman, Zach and I decided to make our last day in Amman as simple as possible: walk to a nearby restaurant; wander through a few shops for last minute mementos and gifts; before using the Lyft taxi service to take us to the University of Jordan where my wife and her colleagues were wrapping up their business trip.

After picking us up at our hotel, the Lyft driver snaked at varied, erratic speeds through Amman’s near constant heavy traffic. On the approach to the University of Jordan’s (UJ) campus, my son spotted a McDonald’s near our drop off point — the UJ’s main gate along Queen Rania Street. Annoying our driver with a u-turn request that put us in front of McDonald’s, we stumbled out the Hyundai sedan (which appeared to be every other car in Amman) and texted my wife to announce our arrival.

As we waited for my wife and her colleagues, we felt like pinballs as the high volume of foot traffic passing near the UJ main gate bounced us around. At 31,000 students, UJ is Jordan’s largest university. It is also the oldest and most prestigious.

While being absorbed into this crowd, I was immediately struck by the high percentage of woman compared to men heading in and out of the UJ campus. It wasn’t even close. Doing a quick headcount (as best I could), I estimated three females for every male student. Just a guesstimate. And, as it turns out, not too far off the actual gender ratio reported by the UJ’s statistical office: Female students at UJ outnumber male students two-to-one. In comparison, females represent 49 percent of Harvard University’s undergraduate population.

________________________________________________________________

Based on their student populations, Jordan’s most elite university is more female-dominated than Harvard. Such is the world we live in today.

More importantly, we are seeing this trend throughout the Middle East and North Africa, not just with respect to tertiary institutions (i.e., higher education), but also with primary and secondary education (grades K-through-12).

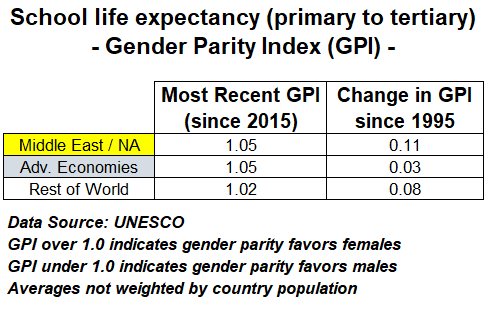

UNESCO has created indexes monitoring the status of women in the world’s education system. Since 1995, the evidence is overwhelming: Women in Islamic countries are increasingly being educated at rates comparable to women in economically advanced countries (e.g., the U.S. and Europe).

This fact will fundamentally change the Middle East.

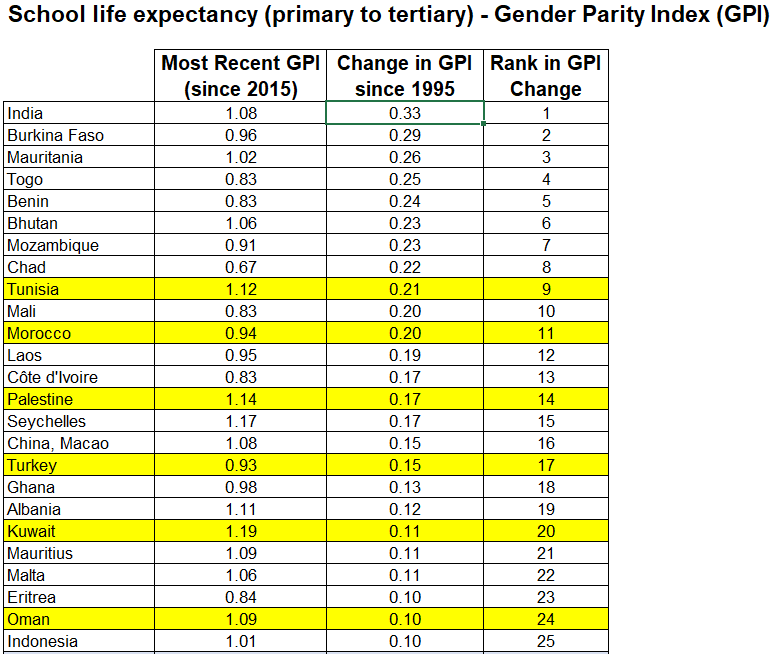

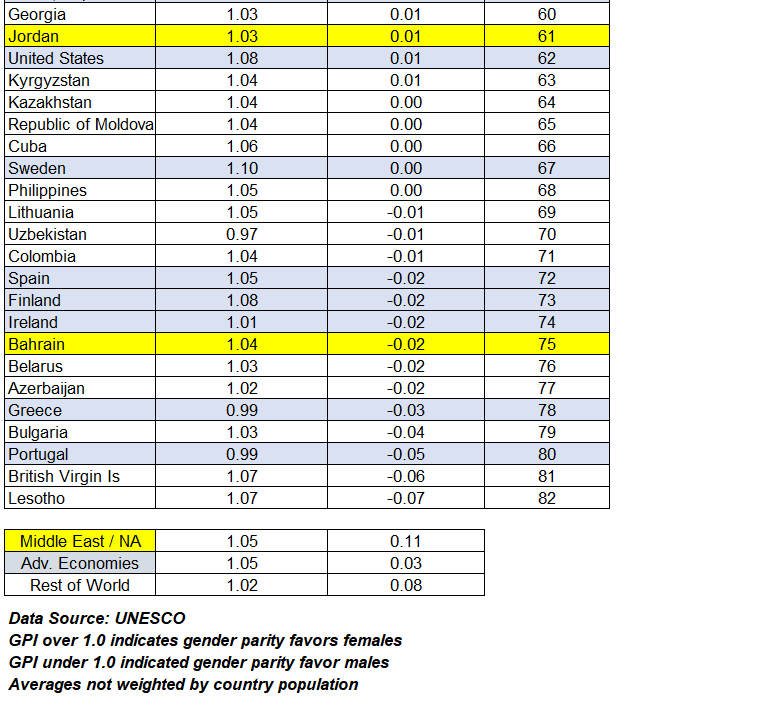

One UNESCO measure is particularly informative: The Gender Parity Index for School Life Expectancy (GPI-SLE). The SLE component is defined as the number of years of schooling from primary to tertiary levels of education. Subsequently, the GPI-SLE is calculated as the ratio of female of school life expectancy to male school life expectancy.

A GPI-SLE equal to 1 indicates parity between females and males. In general, a value less than 1 indicates disparity in favor of males and a value greater than 1 indicates disparity in favor of females.

On this UNESCO measure, women in the Middle East may have already equaled their sisters in the advanced economic world (see table below). For 82 countries with consistent data from 1995 to 2018, each was categorized into one of three categories: Middle East/North Africa, Advanced Economies, Rest of World (see Appendix A for the list of countries and categorization).

The Middle East/North Africa (MENA) countries with reliable data include: Tunisia, Morocco, Palestine, Turkey, Kuwait, Oman, Iran, Jordan and Bahrain.

According to the most recent GPI-SLE, MENA countries have an average GPI-SLE of 1.05, indicating a slight bias in favor of females. This MENA index score is the same as for the advanced economies and slightly higher than all remaining countries (GPI-SLE = 1.02).

It may surprise some that the education systems of Kuwait, Palestine, Tunisia and Oman are more gender biased in favor of females than the United States, Norway, Israel, Denmark, and Finland (see Appendix A). The educational advancement of women in MENA countries defies an arrogant and common assumption about the West’s advantage over Islamic countries in terms of gender equity.

And while the GPI-SLE is just one measure of gender equality in education, other UN-monitored gender equity measures show a similar worldwide pattern to the GPI-SLE (e.g., gross enrollment ratios, adjusted net enrollment rates, adjusted net intake rate to Grade 1, Percentage of female graduates by level of tertiary education).

In terms of education, women living in MENA are rapidly catching up to their counterparts in the advanced economies. And its happened relatively fast. In the above table (2nd column) we see that, since 1995, the increase in the GPI-SLE (i.e., the education system has become less biased towards females) has been greater among MENA countries (Δ GPI-SLE = +0.11), than the advanced economics (Δ GPI-SLE = +0.03), or the remaining countries (Δ GPI-SLE = +0.08). The higher magnitude improvements in MENA countries are due, in part, to those countries having started their gender equity efforts with females significantly more disadvantaged at the beginning of the process.

It should be noted that the educational rise of women in MENA countries mirrors similar increases in other parts of the world. It is not an Islamic-thing, it is a world-thing. And this trend is particularly evident in higher education.

“Despite what history across the globe has told us, women now outnumber men at universities — and it is a trend which is accelerating year upon year in the majority of countries,” Isabelle Bilton wrote last year for Study International News, an independent news service monitoring education trends for international students.

Many theories have emerged explaining this worldwide, systemic shift in education attendance and outcomes favoring females. In summarizing the research on this question, Bilton offered this: “There is no answer to why the gender shift occurred but many researchers have speculated problems occur when students are in school. Boys tend to be less interested and less focused on schoolwork, leading to lower grades at all levels of study. As a result, fewer of them choose — or are able — to enroll in universities.”

But something deeper is going on in Jordan and the Middle East more generally. As girls are rising, boys are falling precipitously. As noted by education researcher and author Amanda Ripley in a September 2017 article for The Atlantic, “In school, Jordanian girls are crushing their male peers. The nation’s girls outperform its boys in just about every subject and at every age level. At the University of Jordan, the country’s largest university, women outnumber men by a ratio of two to one — and earn higher grades in math, engineering, computer-information systems, and a range of other subjects.”

This relative trend between males and females in Jordan is not entirely dissimilar from trends in the U.S. where girls do better than boys on standard tests, are more likely to take Advanced Placement tests, more likely to go to college, and will spend more than a year longer in school over their lifetimes compared to their male counterparts.

But, as Ripley’s research shows, something more pernicious may be happening in the Middle East that is (literally) hitting boys hard. In her article, Ripley shared an interview she conducted with a group of teenage girls at an elite Jordanian secondary school. When the girls were asked why they thought girls do better than boys in school, one 16-year-old student, Nawar Mousa, was quick with an answer: “I do my homework, and I read books. My brother, what does he do? He goes with his friends. He plays PlayStation.”

During her research, Ripley also interviewed a Jordanian family with a 15-year-old son attending an all-boys high school. In the course of the interview, the son acknowledged that is common in his boys-only school for teachers to hit students (boys). The boy’s mother added: “Girls’ schools are better,” she said, “less dangerous.”

Whether we can generalize from Ripley’s research to the Jordanian education system writ large is debatable, but her work does conform to other research in Jordan showing academic achievement is affected by violence in the learning environment. Students don’t learn in threatening environments and gender-segregated schools may amplify those threats for boys.

Half of Jordanian primary and secondary public schools are gender-segregated. While there has long been evidence in the U.S. that girls learn better in all-female environments, boys clearly don’t flourish in all-male environments. Quite the opposite. Boys achieve more academically when more girls are in the environment, according to recent research.

In practice, educational strategies that work for girls also work for boys, and vice versa. The research is unequivocal on this point: What drives academic performance is expectations placed on the individual student, regardless if it is a boy or girl.

“Our research shows that boys will compete for good grades and often achieve them in schools where academic effort is expected and valued,” says Claudia Buchmann, a sociology professor at Ohio State University and co-author (with Thomas A. DiPrete) of the book, The Rise of Women: The Growing Gender Gap in Education and What It Means for American Schools.

________________________________________________________________

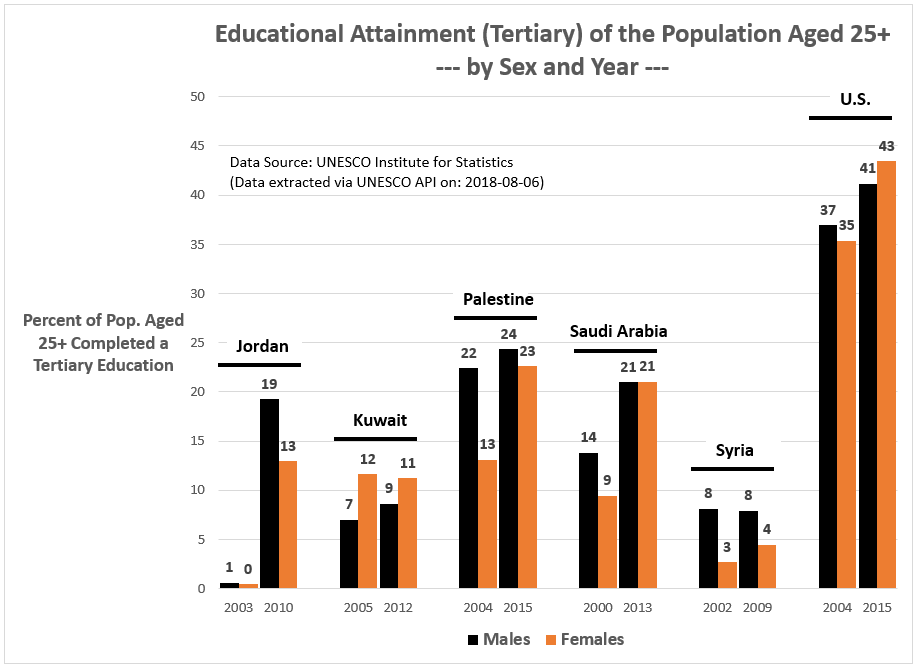

The progress Jordan has made in the past two decades in building its higher education infrastructure can be seen in the chart below. Where in 2000 few Jordanians aged 25 years or more had a higher education degree, in just 10 years 19 percent of men and 13 percent of women had higher education degrees. While these rates are significantly lower than those observed in the U.S., they are comparable to other Middle Eastern countries. Compared to other Middle Eastern countries, over the past two decades Jordan has among the highest increases in educational attainment for women.

Some observers express caution about the educational advancements of Jordanian women given this fact: women may be getting higher education degrees, but it is not translating into comparable employment opportunities.

In Jordan, nearly 27 percent of unemployed university graduates are male, while almost 68 percent are female. In 2013, the World Bank reported a 35 percent unemployment rate among college-educated women, considerably higher than the rate for college-educated men. In fact, the unemployment rate for men goes down with higher levels of education, but for women the exact opposite is true: As women become more educated, the unemployment rate goes up.

In Jordan’s highly patriarchal society where job opportunities for women have been historically limited, the employment rate disparity between men and women is not surprising. However, as more Jordanian women earn college degrees, many will choose to leave Jordan for other countries, such as the United Arab Emirates, where more jobs (and higher paying ones) exist for women.

This brain drain is a critical issue in Jordan today.

________________________________________________________________

Our last activity in Jordan before flying home was to visit with the Chair of UJ’s Political Science department, Dr. Amir Salameh Al-Qaralleh, an imposing figure when standing, but reclined in his office chair with a cigarette in his hand, he was disarming.

Over the course of an hour long conversation, much of it about Syria and the U.S. withdrawal from the Turkish-Syrian border, a number of Dr. Al-Qaralleh’s students popped their heads into his office. One student forgot her notebook for a class and asked if Dr. Al-Qaralleh had paper he could spare. Another asked about a class assignment. And still another asked about an exam.

“Students today,” he said, slightly shaking his head. “They are not self-sufficient.”

But I had a different reaction, first noticing the obvious comfort these students had walking into Dr. Al-Qaralleh’s office, even as he was in a conversation. Where I went to school (University of Iowa, Columbia University), it is unimaginable that I would have walked in on a Department Chair in such a circumstance.

I also noticed that all of the students that asked to speak to Dr. Al-Qaralleh during our meeting were women. That was not random chance, as I’ve seen this pattern before as a college instructor. Of the students that would visit me during office hours, easily three-quarters were women.

When I shared this observation with Dr. Qaralleh, he paused, choosing his words wisely. “Women aren’t afraid to ask for help,” he replied.

Apparently, the reluctance of men to ask for help is a universal phenomenon.

But this anecdotal evidence may also reflect a higher level of engagement found among female students pursuing a higher education in Jordan.

Dr. Al-Qaralleh seemed to agree with this broad generalization.

Apparent is that Jordanian women are getting educated at increasingly higher rates and it is not a transitory phenomenon. Instead, it is proving to be broad-based and sustained, despite the strains put on the Jordanian education system by the influx of over 600,000 registered Syrian refugees into Jordan since the start of the Syrian Civil War.

The rise of women in Jordanian education mirrors similar changes around the globe, but as I’ve documented here, this trend has been more pronounced in MENA countries than in other regions.

In a patriarchal society like Jordan’s, don’t be surprised if in the next decade the question asked among policymakers is less focused on helping Jordanian women achieve educational and economic parity with Jordanian men, but on how to help men keep up with their female counterparts.

__________________________________________________________________

Appendix A:

Appendix B: