By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, February 19, 2018)

“The Number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every thirty Thousand, but each State shall have at least one Representative.”

U.S. Constitution: Article I, Section 2, clause 3

It says a lot about our democracy that our Founding Fathers were worried more about too much representation than too little.

For the U.S. House of Representatives, the “people’s chamber,” the Founders set a limit on representation: a ratio of one representative for over 30,000 citizens (1:30,000). They designed a representative democracy, but not too much of one.

For a comparison, in a theoretical direct democracy, where citizens vote directly on major policy questions, that ratio would be 1:1.

Today, the average House member represents 575,000 vote eligible adults living in 290,000 households. If, when Congress is out of session, members devoted 8-hours-a-day to door-knocking, it would take almost 15 years for a House member to visit every household in their district.

If we do not expect our elected representatives to possess a deep, personal connection to a wide breadth of their constituents, there is no reason to increase the size of the House. If, however, we believe our representatives are too detached from their constituents, such as by space, interests or social hierarchies, then we need to consider changing that relationship.

In his treatise, Politics, Aristotle noted that increasing the number of people in a political unit affects relationships within that unit. With greater numbers come greater levels of individual variation. Sociologist Louis Wirth, in his seminal 1938 article, “Urbanism as a Way of Life,” inferred that such increases in individual variation “give rise to the spatial segregation of individuals according to color, ethnic heritage, economic and social status, tastes and preferences.”

Over a century before Wirth’s scholarship, a similar social dynamic weighed on our Founding Fathers as they debated and created the U.S. Constitution.

James Madison, the fourth President of the United States and the “Father of the Constitution,” dedicated much of his attention in the Federalist Papers to the belief that our national government need not worry about the heterogeneity of interests and preferences in the American federal structure.

In Federalist Paper No. 55, James Madison articulated the basic argument for limiting the number of U.S. House members: “The number ought at most to be kept within a certain limit, in order to avoid the confusion and intemperance of a multitude. In all very numerous assemblies, of whatever characters composed, passion never fails to wrest the sceptre from reason. Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates; every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob.”

James Madison, the co-founder along with Thomas Jefferson of the Democratic-Republican Party, the precursor of today’s Democratic Party, believed it necessary to keep the decision-making powers of representative government in the hands of the few, not the many.

However, despite his siding with Alexander Hamilton and other federalists arguing for a smaller, constitutionally limited number of representatives, a prescient Madison identified in Federalist Paper No. 55 the potential problems associated with too few representatives:

- First, that so small a number of representatives will be an unsafe depository of the public interests;

- Second, that they will not possess a proper knowledge of the local circumstances of their numerous constituents;

- Third, that they will be taken from that class of citizens which will sympathize least with the feelings of the mass of the people, and be most likely to aim at a permanent elevation of the few on the depression of the many;

- Fourth, that defective as the number will be in the first instance, it will be more and more disproportionate, by the increase of the people, and the obstacles which will prevent a correspondent increase of the representatives.

Every one of his four points has materialized since the formation of our representative democracy in 1789. And with the Permanent Apportionment Act of 1929, which fixed the number of House members at 435 and created a procedure for automatically reapportioning House seats after every decennial census, it was ensured that as the country’s population grew, the House would not.

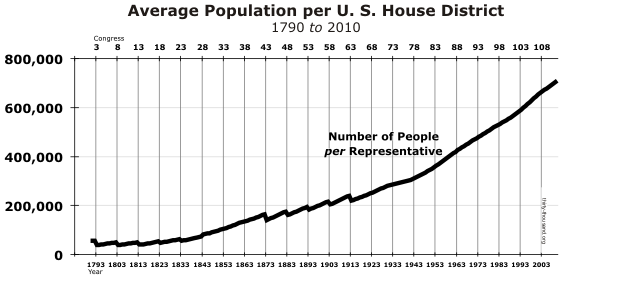

The result is our elected representatives are increasingly distant from the people they represent. The chart below shows the average House district’s population size since 1789 (Note: the chart uses total population, including vote ineligibles such as minors):

As district populations get bigger and often more heterogeneous, it becomes more difficult for House members to stay connected with their constituents. Modern communication technology may increase the ability of a member to communicate with his or her constituents, but such technology does not change the social distance between them.

Can elites represent the interests of the masses? Yes. That is not the problem

Being, or having been, a member of the House is to be part of an elite club. Of the 545 million Americans that have ever lived, only 10,945 have served in the House.

And it requires significant financial resources to get the job. According to OpenSecrets.org, the average 2016 House candidate in spent approximately $465,736 and to win it typically required three times that amount. While not every House member is a millionaire, without either considerable personal wealth or access to other peoples’ wealth, to run for the House is simply impossible for the vast majority of Americans.

Yet, the problem isn’t that half of our national representatives are millionaires. A good argument can be made that our elected representatives should be drawn from the most successful in our society. No, that is not our fundamental problem.

The problem is, instead, that our government’s policies increasingly represent the interests of affluent Americans at the expense of the majority. Our best and brightest aren’t going to Washington to represent their constituents. They go to Washington to represent the political donor class.

In their widely-praised 2014 study, political scientists Martin Gilens and Benjamin I. Page found that American policymaking is dominated by the interests of powerful business organizations and the wealthiest segment of American society.

Using 1,779 policy disputes between 1981 and 2002 in which a national survey of the general public asked a favor/oppose question about a proposed policy change, Gilens and Page assessed opinions on these policy changes by income level (e.g., poor, middle class, affluent).

The following graphs from their paper summarize their findings:

The near horizontal, black line in the first graph indicates the policy preferences of the average American voter do not relate to actual policy outcomes. In contrast, as seen in the upward sloped black lines in the next two graphs, there is a strong relationship between policy outcomes and the policy preferences of economic elites and interest groups.

“Americans do enjoy many features central to democratic governance, such as regular elections, freedom of speech and association, and a widespread (if still contested) franchise,” conclude Gilens and Page. “But we believe that if policymaking is dominated by powerful business organizations and a small number of affluent Americans, then America’s claims to being a democratic society are seriously threatened.”

Whatever the Founding Fathers intended in setting the maximum ratio of U.S. House representatives to constituents, the result is a federal government responsive to the policy preferences of the most privileged Americans, and unresponsive to average Americans.

If we, as a country, are comfortable with such influence disparity, then changing the size of the U.S. House from the current 435 members is unnecessary. If, however, this imbalance is incompatible with our expectations and requirements for representative democracy, it is time to seriously consider increasing the number of members in the U.S. House.

Canadian novelist John Ralston Saul articulates well the practical goals of representative democracy:

“The strength of representative democracy is its ability to slow down those in power who wish to govern by blank cheque, but also those not in power who wish to yank the state about on the sole basis of their self-interest,” he writes.

Based on Gilens and Page’s research, the American state doesn’t get yanked very often by the average American. Without some structural change, the American democracy is stubbornly skewed towards the interests of the elite. And, if we agree this is a problem, we need to find the essential institutional change that most directly offers a remedy.

Per Madison’s insights in Federalist Paper No. 55, the simplest answer is to make congressional districts significantly smaller.

A Rationale for Increasing the Size of the U.S. House to 6,000 Members

Lets start with what the U.S. Constitution itself. With a current voting eligible population of 250,056,000, the Constitution limits the size of the U.S. House to 8,335 members — which is roughly two-thirds the size of the average crowd at a Big Ten men’s basketball game. At that numerical size, the House chamber would need to be the size of the MCI Center in Washington, D.C.’s Chinatown district or Michigan State University’s Breslin Center.

But, before deciding on the ideal size of the House, let us establish an ideal goal towards which to aim.

Here is one idea:

At the House level, an elected representative should have the ability to meet most vote eligible person in their district within a legislative term (2 years). And if the representative can meet his or her constituents, so could any other person living in the district that may want to run for Congress.

Is that asking a lot? What is representative democracy if not the principle that elected officials should represent a group of people with whom they are personally familiar?

Bringing Democracy Back to the People

Representation is a tangible intra-human interaction, not an abstraction. So, let us build a U.S. House of Representatives with that in mind. Let us create House districts small enough that a representative can meet every eligible voter within a reasonable amount time.

How small would congressional districts need to be for a House member to have a feasible chance, if they so choose, to meet most of their constituents within a two-year term? That is a hard question to answer.

Madison may be right again: “No political problem is less susceptible of a precise solution than that which relates to the number most convenient for a representative legislature.”

But he is wrong.

Generally, Madison and the Federalists feared if the House chamber was too populated, it would become unruly and incapable of rendering decisions. Madison writes in Federalist Paper No. 55, “The number ought at most to be kept within a certain limit, in order to avoid the confusion and intemperance of a multitude.”

The Federalists were obsessed with preventing mob rule.

However, it is not clear where the Founding Father’s came up with the 1:30,000 ratio in the Constitution or how that would avoid the formation of mobs. After reading Madison’s “Notes of Debate” from the Constitutional Convention in 1786, apart from their general desire to keep the House chamber small enough to avoid unruly cliques, the Founding Fathers offered no concrete rationale for the 1:30,000. It appears to be nothing more than a realization that only 55 men participated in the Constitution Convention sessions and that number represented roughly 1 in 30,000 citizens in 1787.

The number we are going to compute here will try to be more rigorous.

As we’ve argued, today’s House districts are too large (in population) for a House member to have a plausible chance of meeting a large percentage of their constituents during a two-year term, much less meaningfully represent the multitude of interests in their district. So, what is the number of House members that will make congressional districts small enough for those outcomes to be more likely?

I estimate the number is somewhere around 6,000 members, which is the point where each House district would contain around 20,000 households (or about 40,000 vote eligible constituents). To talk to all of them it will require meeting with 27 households per day for two years. Combine door-knocking with a healthy number of large audience events and it will be possible (but not easy) for congressional incumbents and candidates to talk to a sizable percentage of their constituents.

Wouldn’t Voters Prefer to be Left Alone?

The circumstantial evidence does not seem to support the electoral value of political candidates meeting voters face-to-face. In the age of mass media, the internet, and highly-targeted direct mail campaigns, a candidate doesn’t need face time with voters to get his or her message to them.

A good example is the 2016 presidential election. Republican primary candidates, Ted Cruz and John Kasich, visited New Hampshire for more days than any other Republican candidate, including Donald Trump. Yet, neither garnered more than 16 percent of the primary vote; whereas, Trump gained 35 percent of the vote.

However, there is substantial empirical research confirming the critical importance of door-to-door canvassing by candidates. Using a field experiment in a 2010 local election, George Mason University professors Jared Barton, Marco Castillo, and Ragan Petrie, found that personal contact between candidates and voters was more persuasive than literature drops where the candidate did not meet the voters.

They concluded: “Voters are most persuaded by personal contact (the delivery method), rather than the content of the message. Given our setting, we conclude that personal contact seems to work, not through social pressure, but by providing a costly or verifiable signal of quality.”

What possibly could go wrong (or right) with a 6,000-member House of Representatives?

This essay’s argument for a larger U.S. House is predicated on these findings and assumptions:

- Policy outcomes from the current U.S. House misrepresent the interests of the majority of Americans and is biased towards the interests of the wealthy.

- This policy misrepresentation is a function of the selection bias associated with U.S. House elections, where only wealthiest can run for office, and the money required to win excludes segments of society lacking access to significant monetary resources. The result is U.S. House elections that are prohibitively expensive, non-competitive (incumbency bias) and unrepresentative.

- Personal, face-to-face contact between legislator and constituent is superior to indirect contact, such as through direct mail, TV/radio advertising, and mass emails. Voters, all else equal, will prefer candidates they’ve met.

- Smaller House districts will encourage candidates to spend more face-to-face time with constituents.

- Smaller House districts will make individual House races less expensive and within the realm of possibility for people of relatively modest means to win House elections.

- Therefore, with smaller House districts, the interests of average Americans are more likely to be considered during the policymaking process.

Is there empirical evidence supporting this last point? We could compare the world’s largest legislatures to smaller ones in the democratic world today. For example, in absolute numbers, the European Parliament is the largest with 751 legislators (one legislator per 656,527 people), followed by the German Bundestag with 709 legislators (one legislator per 104,109 people).

But the proper comparison is based on the relative size of the legislature vis-a-vis the population size. A U.S. House with 6,000 members, for example, would have one House member per 54,000 people. That would be comparable to the United Kingdom’s House of Commons (650 members) with one House of Commons member for every 45,000 people. Finland and Sweden have one lower house legislator for every 27,000 people.

On the other end of the spectrum is the U.S. House, with the lowest ratio of members to people (1 to 733,000). The U.S. is on par with countries like Pakistan (1 to 574,000), Bangladesh (1 to 554,000), and Nigeria (1 to 492,000).

Sadly, very little cross-national or intra-national research exists on the effects of legislature size on public policy or political representation. However, what research does exist is generally mixed regarding the benefits of large legislative bodies.

In 1971, the Citizens’ Conference on State Legislatures (CCSL) described the New Hampshire House, with 400 members for a population of 700,000 people, as a place “where 15 people made all the decisions, and if you were among the other 385, you just watched, part of an onlooking audience rather than a full- fledged member.”

Writing for Governing magazine years later, Alan Ehrenhalt noted that in 2000, among the 400 New Hampshire citizens voted into the state house, one was a convicted forger and another advocated violence against police.

While that result may argue against enlarging legislature, it actually reinforces its central benefit: larger legislatures bring in a wider of range of citizenry backgrounds. What, you don’t want forgers in your U.S. House of Representatives? You are convinced our current House members are significantly above such behavior? Please feel free to check out this sobering website that ranks the most corrupt U.S. Congress members in history: Ranker.com. (Spoiler alert:) It is a long list.

But other problems have also been found with larger legislative bodies.

In their 1999 study of state spending, University of Southern California professors, Thomas Gilligan and John Matsusaka, found that the larger Senate (upper house) chambers, spend more money and raise more revenues: “The more seats in the upper House of the legislature, the more the government spends and the more revenue it collects,” they concluded. “A one-seat increase in the upper house is associated with a 0.38 percent increase in total spending.”

Other potential problems with enlarging the size of the U.S. House from the current 435 to 6,000 members would be:

- Where is the office space to accommodate 6,000 House members and their staffs?

- Where will they meet when the full House is in session? The current House chamber only seats a fraction of that number.

- The cost of governing (member and congressional staff salaries, office space, etc.) could be as much as 15 times higher

- Even if smaller districts translates into lower campaign expenditures per House race, the overall cost of House elections would skyrocket.

- It will put more power in the hands of the House leadership.

- House members represent more than just the best interests of their district, they also represent the country — a larger House size might make members more parochial and lessen their attention to broader national interests.

- For all the effort of increasing the House to 6,000 members, policy outcomes might remain biased towards wealthy interests.

There is no question, there are advantages to small legislatures and some of those benefits should be not be given up lightly. Summarizing years of their organization’s research, the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) lists some of the benefits of small state legislatures:

- Fewer legislators does not mean less responsive legislators. Using modern communication mechanisms, a legislator can easily reach, and be reached by, many more constituents.

- Legislative elections will be more competitive and encourage greater voter participation.

- In a smaller body, the role of a legislator will be more prestigious and more satisfying. A smaller legislature increases the responsibility of each member. Individual legislators have more opportunity to influence decisions. Each legislator should be more visible and therefore more responsive to the voting public.

- With a smaller legislature, there will be better discussion and clearer debate. There is more opportunity for each member to make his or her views known, to have his or her voice heard.

- Larger legislatures tend to have more committees. Too many committees result in overlapping and fragmentation of work–making it more difficult for a legislature to formulate coherent, comprehensive policies on broad public questions.

- Large legislative bodies cost more.

But the NCSL also offers some potential benefits from large state legislatures:

- The more the members, the fewer the constituents. With fewer constituents, a legislator is more likely to have face-to face dealings with them.

- One political party can more easily dominate a smaller-sized legislature. A smaller-sized legislature also may increase regional rivalries, particular between rural and urban areas.

- Relatively few political positions are well known by the general population. Reducing the number of legislators probably will not change this fact.

- The legislative process was not intended to be neat and efficient. The legislature is designed to provide a cross-section of all points of view. Legislators are to study, debate and argue, and finally reach a compromise position that is acceptable to a majority of members.

- A large number of members allows for a more effective division of labor and specialization. The oversight of administrative agencies is greater among larger legislatures.

- There is a greater correlation between a state’s population and legislative costs than between legislative size and cost.

Preliminary Cross-national Evidence on Size of Legislatures

While little cross-national research exists on the effects of legislature size on representation, political participation and policy outcomes, there is some.

The World Bank has been consistently tracking income inequality (as measured by the GINI Index) for over two decades. One hypothesis on the effect of large legislatures is that they will better incorporate the economic interests of middle- and lower-income citizens, which should result in economic policies that reduce income inequality. In fact, in a simple cross-sectional, cross-national analysis, we do see evidence that countries with relatively larger legislatures (i.e., fewer people represented per legislator) have lower levels of income inequality (see chart below):

Of course, the causation could be in the opposite direction. That is, countries with low income inequality created larger legislatures because a broader cross-section of society was consulted during the democratic founding process. Nonetheless, there is correlational evidence that the size of a country’s legislature does relate to levels of economic inequality.

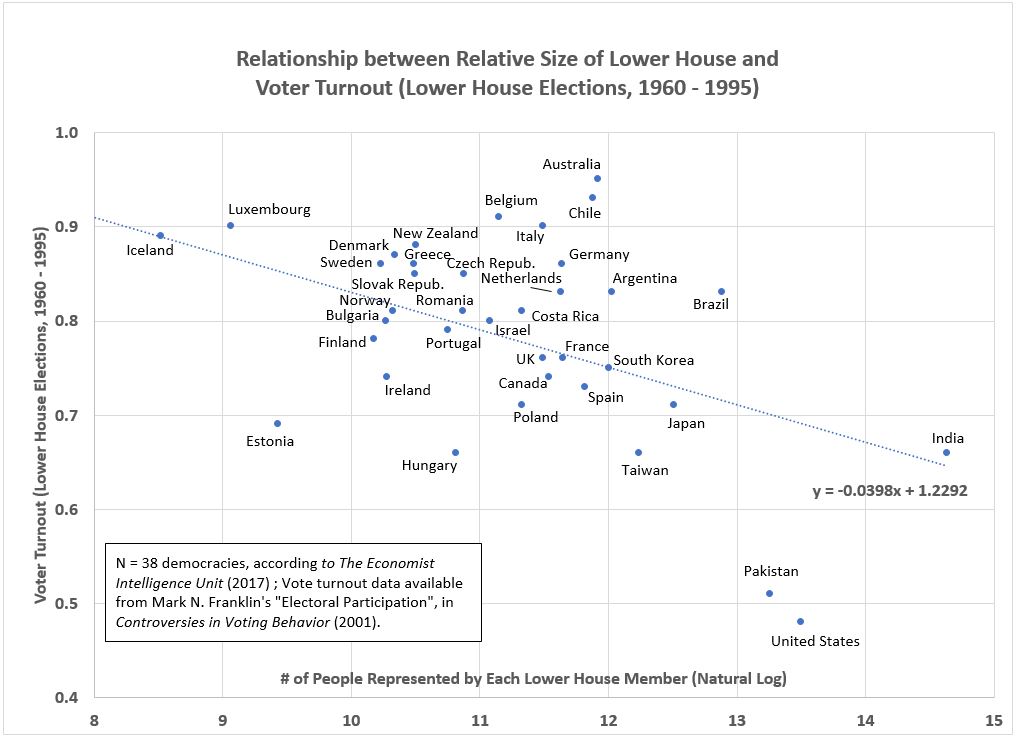

There is also evidence that relatively larger legislatures encourage stronger voter participation and turnout. Using voter turnout data provided by political scientist Mark Franklin, we see a strong negative correlation between the number of people each legislator represents and voter turnout for lower house elections (see chart below):

The arguments in support of small and large legislatures elicit a wide range of research questions that would need to be answered before we muck around with the size of the U.S. House.

For example, would a 6,000-member House lead to a geographically-dispersed, hierarchical structure where only “senior” House members (e.g., the current 435 members) would maintain offices on Capitol Hill, while the remaining “backbenchers” would remain in their home districts and participate in committee meetings, floor deliberations and votes through teleconferencing or other remote services?

Is there a benefit in not having all House members residing in the nation’s capital? Could the geographic dispersal of House members constrain the influence of lobbyists and special interests?

Without a doubt, a significantly larger U.S. House of Representatives will require brand new thinking on the design and function of legislatures.

A small U.S. House is not working — Let us consider making it bigger

We know the policy implications of small U.S. House, and it is set of policies that reflect the interests of the few over the many. Therefore, this country should seriously consider a major structural overhaul of its national lower house.

This essay is not attempting to outline in detail the mechanics required to increase the size of the House. Instead, it is offering a theoretical rationale for not just increasing the size of the U.S House, but to do so on a transformational scale.

Allowing the House to increase incrementally over time (as it did before 1929) will probably not address the policy bias problem. To do that, individual House members must be spatially closer and more accountable to all of their constituents. A larger U.S. House needs to be large enough (i.e., much smaller districts) so that people of modest means can at least contemplate the idea of running for Congress.

Advertising, social media and direct mail campaigns won’t go away just because House districts are smaller. But with small House districts, expensive broadcast television and radio ad buys become less attractive.

For example, in my home state of Iowa, the 1st U.S. Congressional District covers two local TV markets (Cedar Rapids/Waterloo, and Dubuque). Their coverage areas correspond fairly closely to the 1st District’s boundaries. Today, it makes sense for a congressional candidate to spend a lot of money on broadcast TV ads. And only well-funded candidacies can do that. On the other hand, if Iowa had 60 U.S. House districts, district boundaries would be roughly the size of an Iowa county. At that size, expensive broadcast TV/radio buys make much less sense.

Instead, small district will increase the potential for an underfunded but hardworking doorknocker to beat an entrenched incumbent. In a 6,000-member House, hard work will be a legitimate substitute to campaign money and that will scare the hell out of current House incumbents. If incumbents aren’t able to connect with their constituents on a personal level, the days of 90 percent re-election rates will be over.

And any idea that scares the hell out of incumbents, can’t be all bad.

K.R.K.

====================================================

Addendum:

I did’t address the U.S. Senate in this essay, which likely contributes to the elite bias in national policymaking. Therefore, any effect of changing the size of the U.S. House will be muted by the current structure of the U.S. Senate. Nonetheless, changing the size of the U.S. House should still bring an increased level of accountability and responsiveness of that chamber to the opinions of average Americans.

====================================================

{Send comments to: kkroeger@nuqum.com}

About the author: Kent Kroeger is a writer and statistical consultant with over 30 -years experience measuring and analyzing public opinion for public and private sector clients. He also spent ten years working for the U.S. Department of Defense’s Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness and the Defense Intelligence Agency. He holds a B.S. degree in Journalism/Political Science from The University of Iowa, and an M.A. in Quantitative Methods from Columbia University (New York, NY). He lives in Ewing, New Jersey with his wife and son.