By Kent R. Kroeger (NuQum.com, October 26, 2019)

_________________________________________________________________

This essay documents my challenges, observations and an occasional, unintended interpretation of their broader meaning during my family’s recent travels through Oman and Jordan.

This is the first essay in a series.

_________________________________________________________________

[Note: The names in this essay have been changed to protect identities.]

If the world seems on the verge of exploding, you are probably watching too much news on cable TV.

On the other hand, there may be something real going on. Something so fundamental that even the U.S. can’t alter its trajectory.

In the past few months, we have had protests in Hong Kong, Ecuador, Chile, Lebanon, Iraq, UK and Jordan. Whether it is teachers, pro or anti-Brexiteers, students, or disgruntled commuters, anger appears to be rising among the world’s citizens.

The dark forces exploiting this growing discontent are gaining power so fast, Washington Post columnist David Ignatius is convinced the time is now for the U.S. to extend its regime-change magic to Lebanon. [What could possibly go wrong?]

But is this apparent increase in worldwide protest significantly different from the recent past? The answer is a tentative ‘yes.’

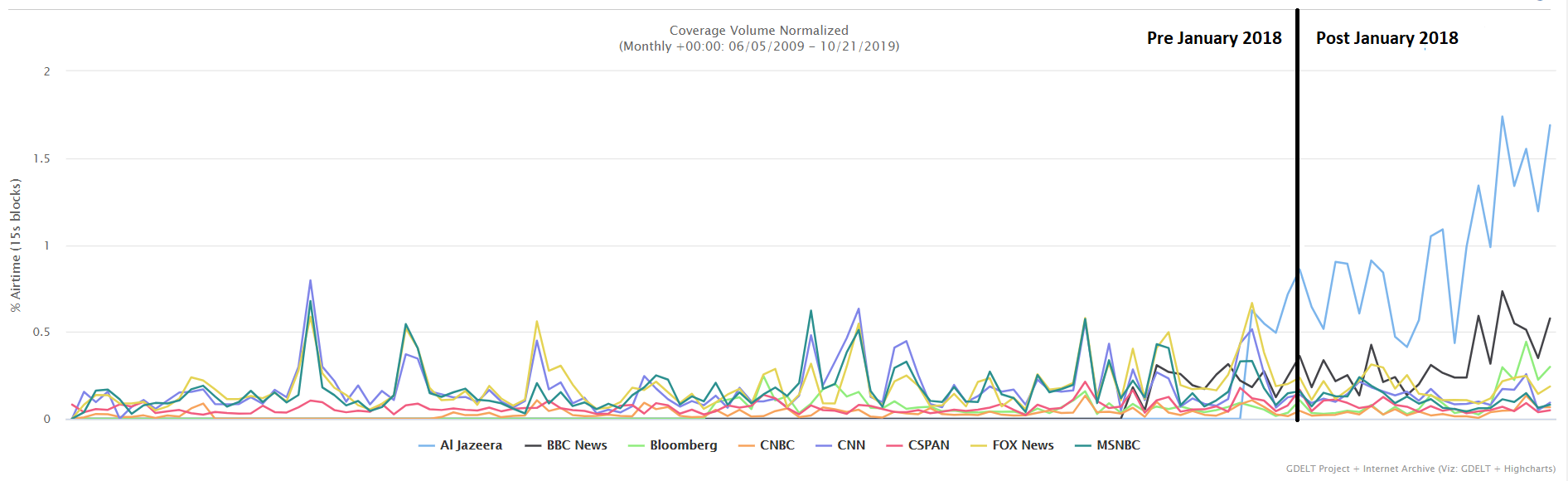

Let us look at the data. According to the GDELT project, the term ‘protest’ in the world’s TV news has been on the rise since January 2018, particularly on Al Jazeera and the BBC World Service.

Figure 1: Frequency the term ‘protest’ used in major news broadcasts

We are repeatedly told by the news media that, since the election of Donald Trump, the world has become more agitated (and Figure 1 suggests this is true). And this tumult has had profound consequences on countries otherwise free of conflict and violence.

Nowhere more so than Jordan and its capital city of Amman.

Amman, Jordan rests in the middle of it all

Human settlements in Amman, Jordan date back over 9,000 years, but the city today doesn’t look a day over 200-years-old.

Amman is like a pair of old leather shoes that are comfortable. Clearly having seen more prosperous days, the city is ragged but relaxed. It’s worn down but durable.

My son and I had just arrived in Amman from Muscat, Oman, the day before when a hired driver picked us up at our hotel near the old city center.

Our driver, Farouk, a middle-aged Palestinian and father of four, said he was eager to show us his city as he took one last drag on his half-smoked cigarette before snuffing it out. [Everyone in Jordan smokes, or so it seemed. Hookah lounges were everywhere.]

As our hotel was in old Amman, near the former parliament building, we were walking distance to most everything we needed during our four-day stay. Still, an informal driving tour is a useful introduction to any new city.

Farouk’s English was far better than my Arabic so after a few minutes of exploratory small-talk, we settled into a conversational rhythm that seemed to facilitate mutual understanding.

Soviet-era Russian proverb: To learn about someone’s politics, avoid talking politics.

When traveling abroad, it is advisable to avoid conversations about politics, particularly in a country like Jordan which, despite the generally laid back demeanor of its citizens, is still a constitutional monarchy where political speech and press freedoms are significantly constrained. The democracy watchdog group, Freedom House, classifies Jordan as only ‘partly free,’ scoring the country a 37 out of 100 on their Freedom Index. In its 2019 report on worldwide press freedom, Reporters without Borders (RWB) ranked Jordan 130th out 180 countries (Afghanistan ranks higher than Jordan on the RWB’s Press Freedom Index).

Nevertheless, in a region where one’s very existence can be a potent political statement, politics hangs in the bone-dry Jordanian air like a low-frequency hum. You see politics everywhere, if you look for it.

Using an unscientific sampling method (i.e., any taxi cab that passed Farouk’s car), I estimated that about 1-in-20 Amman taxi cabs had Saddam Hussein’s image pasted on the back bumper or window. Not a surprise, considering the former Iraqi strongman was one of the first Arab leaders to embrace the Palestinian cause, at least superficially; but the ubiquity of his image still begged the question: “Why Saddam Hussein?”

“He is admired by many Palestinians,” Farouk said. He didn’t elaborate. He didn’t need to.

During his rule, Saddam Hussein granted equal-rights status to roughly 35,000 Palestinian refugees living in Iraq — most of whom came to Iraq in one of three waves: (1) the 1948 war surrounding Israel’s creation, (2) after the Six-Day War in 1967, and (3) and in the 1990s after many Palestinians were expelled by Gulf states opposed to Iraq’s occupation of Kuwait.

“Portraying himself as a defender of the Palestinian cause for statehood, Saddam gave them subsidized housing and the right to work — rare privileges for foreign refugees that bred resentment among many Iraqis,” according to journalist Ahmed Rasheed.

In 2017, reacting to that popular resentment, the current Iraqi regime rescinded those special citizenship rights for Palestinians leaving the roughly 10,000 Palestinians still in Iraq feeling particularly vulnerable.

Not every Jordanian Palestinian keeps warm feelings about Saddam, however. One such person on my Reddit feed (“Samir”) explained the Jordanian fondness for the former Iraqi leader as rooted in his selling oil to Jordan in the 1990s at preferential prices in exchange for the Jordanians helping Saddam escape U.N-imposed sanctions by utilizing Jordan’s Aqaba port.

“Let us not forget that Iraq under his reign tried to blow up some Amman hotels in the 1990s hosting Americans,” Samir noted.

___________________________________________________________________

Farouk abruptly merged onto Khaled Ben Al-Walid Street, a major road artery in Amman’s central district, cutting off a taxi cab in the process. As he darted back and forth between lanes of fast-moving traffic, I felt like I was on Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride at Disney World.

As our speed settled into a crawl as we came upon a minor traffic jam, Farouk pointed to some nondescript buildings to our left. “Jabal el-Hussein refugee camp,” he said.

“A Palestinian camp?” I asked.

“Yes,” he responded. “Created after 1948 (Arab-Israeli war). But now also Syrians and Egyptians.”

Built in 1952, the camp originally housed 8,000 Palestinian refugees in a area covering 0.4 square kilometers in northwest Amman, not far from the The Citadel, a Roman-era complex of ruins in the heart of Amman. Today, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) says the camp’s population exceeds 29,000 registered refugees, but unofficial population estimates report the number of people living in Jabal el-Hussein camp is between 40,000 and 60,000 people, including many Syrian refugees who escaped that country’s recent civil war.

My first surprise was that the Jabal el-Hussein camp looked like just another Amman neighborhood. The buildings were closer together, perhaps. But, otherwise, it would be hard to know where the camp begins and where it ends.

After over 60 years in existence, many Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan have morphed from transitory tent cities to complex, permanent communities that, by all appearances, seem integrated into the host country’s economy.

“Is it safe for us to walk around the camp?” I asked timidly, not wanting to offend our host.

“Safe?” he said with a smile. “This is Jordan. Of course, it is safe.” A refrain we would hear more than once while in Jordan.

___________________________________________________________________

Before starting our driving tour of Amman, I had asked Farouk if we could visit one of the Amman’s Palestinian refugee camps. He didn’t respond at the time, which I assumed was either a function of the language barrier or that I was asking something politically sensitive.

So when in the middle of our car tour he pointed out the Jabal el-Hussein camp, I was surprised. Pleasantly so. And even more so as he continued talking about refugees more broadly — specifically, their impact on everyday life in Jordanian society.

“We have many refugees because we are safe,” Farouk started. “But our government doesn’t have the money to take care of everyone.”

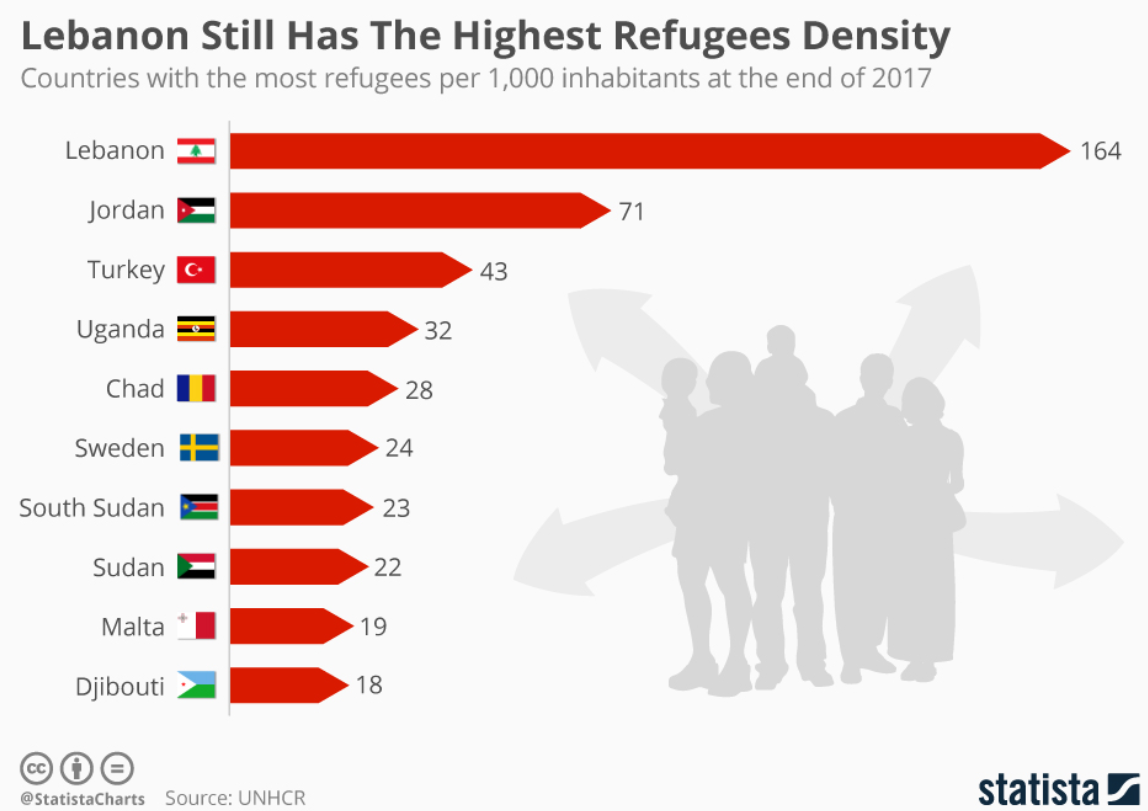

Behind only Lebanon, Jordan has 71 refugees for every 1,000 Jordanian citizens. In third place is Turkey, with 43 refugees for every 1,000 Turkish citizens.

Figure 2: Countries with highest refugee density (2017)

But, factoring in undocumented refugees, one World Bank official estimated that one-out-of-three people living in Jordan in 2015 was a refugee. In a country of 9.7 million, that is around 3 million refugees.

Whatever the true figure, refugees are a major cost factor within the country’s public and private economies.

“Jordan is now hosting just over 650,000 registered Syrian refugees, with some estimating the total number, including unregistered persons, closer to double that,” according to Mark Plant, Chief Operating Officer of the Center for Global Development (Europe), an independent research organization. “At the same time, international partners, notably the International Monetary Fund (IMF), have been insisting that Jordan take actions to bring down government debt to more sustainable levels through increasing fiscal discipline to tame government deficits. These dual imperatives by the international community — host more refugees and tame the budget — seem to put Jordan in an untenable situation as long as the refugee crisis continues.”

In terms of Jordan’s financial ability to handle such a large refugee population, the evidence is mixed. On the positive side, at 30 percent of GDP, Jordan has a relatively small amount of external debt (i.e., total public and private debt owed to nonresidents repayable in internationally accepted currencies). In terms of gross government debt, however, Jordan possesses one of the highest debt levels relative to GDP at 96 percent (for comparison, the gross government debt relative to GDP for the U.S. is 107 percent). For all countries, the average gross government debt relative to GDP is 60 percent, according to the IMF.

Jordan receives substantial support from the international community. But, even with that assistance, Jordan’s government budget is strained…and the people feel it.

__________________________________________________________________

More than once Farouk reminded me that the Palestinians in Jordan “are Jordanians.” And he wanted to make it clear that Jordanian support for the Syrian and Iraqi refugees is evidence of Jordan’s strong humanitarian history, but that Jordanian citizens — most of whom are Palestinian — cannot be of secondary importance.

Farouk’s sentiment should sound vaguely familiar to Americans. Replace “Syrian refugees” with “Mexicans” and “Jordanians” with “Americans” and you have Donald Trump’s core immigration platform.

And it is not just working-class Jordanians extending this opinion. Ahmed, a Jordanian academic and former senior government official for Jordan’s King Abdullah told me during dinner, “Few countries have more refugees for its population size than Jordan — and we have expertise on refugees issues that we need to share — but we also have limits.”

Concerned that Jordan’s government budget deficit was too high to maintain long-term, he cited Jordan’s recent teachers strike that resulted in Jordanian teachers getting a 35 percent pay raise. “The government didn’t even get the teachers to accept performance pay standards,” he lamented.

The Jordanian teachers strike underscores the risk in underestimating the potential for Jordan’s domestic stressors to impact regime stability. Nevertheless, casual conversations with Jordanians leave a strong impression that popular support for the King Abdullah is high and not immediately threatened.

___________________________________________________________________

As Farouk dropped my son and I off at our hotel following our tour, I again asked if there were any areas near our hotel we should avoid walking around at night. He clearly thought I was just another overly cautious, misinformed American — but, in my defense, Amman is a big city and like any city it has ‘bad areas.’

“You are safe,” he assured me. “This is Jordan.”

Farouk’s national pride notwithstanding, a variety of crime statistics do confirm that Jordan is relatively safe, at least compared to its neighbors.

According to Numbeo.com’s survey-based Crime index, Jordan is relatively crime-free compared to its Arab neighbors, ranking 62nd out of 123 countries. In comparison, the Palestinian Territories rank 46th, Lebanon 63rd, Iraq 73rd, Egypt 81st, and Syria 114th. Using a more concrete metric — annual homicide rate — Jordan ranks 67th out of 195 countries with an annual murder rate of 1.4 murders per 100,000 inhabitants, compared to 9.9 for Iraq, 4.0 for Lebanon, and 2.5 for Egypt.

But it is not on individual-level crime statistics that Jordan stands out. Saudi Arabia is much safer than Jordan, but at a tremendous cost to Saudi personal freedoms. It is at a more macro-level that Jordan truly looks like a regional outlier.

In Amman, we were only 55 miles from the Syrian border at the Jaber Border Crossing (similar to the distance between Philadelphia and Dover, Delaware) and 130 miles from Damascus, Syria (similar to the distance between Philadelphia and Washington, D.C.). Yet, the problems of Jordan’s northern neighbor could not have felt more distant. Even as news coverage of Turkey’s incursion into northern Syria dominated the regional news channels, there was no evidence that people in Amman were overly concerned. Our hosts occasionally would make glancing references about the Turkey-Syrian-Kurdish conflict, and only as a contrast to Jordan’s general state of peace and generosity in taking in Syrian refugees.

“You can’t blame the Syrians here in Jordan for not wanting to go back to Syria,” commented Ahmed. “They fear reprisals from (Bashar al) Assad’s police state.”

___________________________________________________________________

My most vivid contrast to Jordan was the country of Oman, where my son and I had spent the previous week prior to arriving in Amman.

Other than Islam’s omnipresence, Jordan is an antipode to Oman. Modernity has settled into Oman with the subtlety of a Donald Trump applause line. The newness found everywhere in Oman’s capital, Muscat, has a calculated presence amidst a still conservative Islamic society, suggesting Muscat as a ‘future Dubai’ at one moment and, at another, emitting the aura of a stubbornly ancient culture. It’s a tension that may work in Oman’s favor in the long run. Or it may not.

What Oman and Jordan have in common is their status as enclaves of peace and stability surrounded by neighbors that are either being bombed or bombing someone else.

Here’s a quick rundown of Jordan and Oman’s neighborhood:

Egypt’s Sisi regime is facing its biggest domestic protests of its relatively brief reign. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict has regressed into an active, never-ending crime scene disproportionately favoring the perpetrator over the victim and showing no signs of changing that dynamic.

Syria is the mess du jour for now. But Iraq always waits in the anteroom ready to take over that role in a moment’s notice.

Lebanon is facing its largest mass protests in decades. And, on Lebanon’s southern border, Hezbollah remains locked in a continuous standoff with Israel while it also support’s Assad’s efforts to regain a tight grip on his people.

Saudi Arabia and UAE continue their cruel proxy war with Iran in Yemen, leaving the most vulnerable in Yemen on the constant brink of death by famine and disease.

And, yet, there is Jordan in the middle of all that chaos, appreciating their relative quiescence, but always aware that it could end.

I asked a prominent Jordanian political scientist what Jordan’s secret is to maintaining stability. It’s not like Jordan controls vast reserves of oil and natural gas to buy social tranquility. They are not a worldwide IT hub like Israel.

How does Jordan do it?

The professor leaned back in his chair, stroking his chin. “If I knew, I’d bottle it and sell it to the world.”

- K.R.K.

Please send comments to: kroeger98@yahoo.com

_________________________________________________________________

Second essay: On the Road to Wadi Rum