By Kent R. Kroeger (NuQum.com, March 12, 2020)

Wealth, tourism and inexperience with communicable diseases are significant correlates with the current nation-level distribution of confirmed cases of COVID-19 (the disease caused by the coronavirus).

Using nation-level COVID-19 data from the World Health Organization (WHO) and socio-economic data from the World Bank, I developed a cross-sectional linear model to explain why, as of 10 March, some countries are seeing more confirmed cases of COVID-19 than others.

My initial findings are, on the one hand, unsurprising:

- All else equal, countries with larger populations have more confirmed cases of COVID-19;

- Countries with a high percentage of annual deaths from communicable diseases are seeing relatively fewer COVID-19 cases (mostly African, SE Asian, and Latin American countries);

- China has a disproportionate number of COVID-19 cases, even given its large population size;

And, in other cases, more thought-provoking:

- Countries with higher national incomes per capita are experiencing higher numbers of COVID-19 cases;

- Countries with higher numbers of tourists entering the country are experiencing higher numbers of COVID-19 cases.

[The linear regression model results can be found in the Appendix below]

The linear model accounts for 71 percent of the variance in confirmed COVID-19 cases on a national level.

Residual Analysis

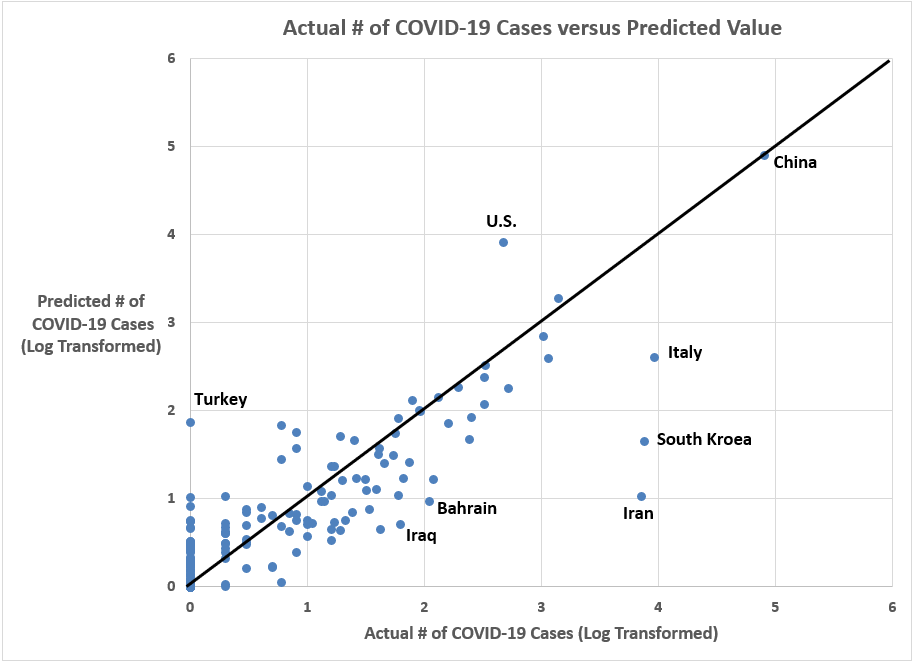

Perhaps more interesting than those factors found to be significant correlates with COVID-19 cases were those countries where the model did not fit the data very well (see chart below).

Two countries in particular stand out in this chart: Turkey and the United States. Both have predicted values for the number of COVID-19 cases significantly higher than their reported numbers. As of 10 March, the U.S. reported 472 cases; whereas, the model suggests — based on the previously discussed variables — that the U.S. should have around 8,350 confirmed cases. Likewise, Turkey had not reported any cases as of 10 March, though the model predicts Turkey should have around 75 cases by now.

Given Turkey’s population size, economic wealth and sizable tourism industry, it is hard to believe there are no COVID-19 cases in the country. My presumption is that they are not testing for the coronavirus in any substantive way.

In the case of the U.S. we are faced with choosing one of two explanations: (1) Either the U.S. has done an unparalleled job of keeping the coronavirus from spreading, or (2) the U.S. has failed to adequately test for the coronavirus and thousands of Americans (possibly as many as 8,350 as of 10 March) have contracted this virus but have not been identified by the health care community and the CDC.

I want to believe the former explanation, but I’m afraid the answer is the latter.

With Vice President Mike Pence’s announcement last week that 1.1 million coronavirus tests would be distributed to qualified labs throughout the country, some optimism that the U.S. government is catching up to the gravity of the crisis. Unfortunately, the estimated U.S. infection numbers presented here tell a different story (see Table 1 below).

Using coronavirus test result numbers collected by British journalist Charlotte Gracias, the 1.1 million tests ordered by the U.S. government may not be near enough to handle the scale of this virus outbreak. If, in fact, there were 8,350 Americans with the coronavirus on 10 March, random testing at a national level would require over 500,000 Americans would need to be tested to find the positive cases. However, most subjects require two tests to determine if they carry the virus, meaning the U.S. will need over 1 million test kits to handle the magnitude of the outbreak on 10 March.

That was three days ago. Since then, the number of confirmed cases in the U.S. has risen from 472 to 1,268 (an over 160% increase). The U.S. government’s 1.1 million test kits won’t be completely distributed until next week (at the earliest). Yet, to handle this crisis, the U.S. already needs twice that number to handle the virus’ spread since VP Pence’s announcement.

This is a public health crisis unlike anything we’ve experienced since the 1918 Spanish Flu.

Implications

As this health crisis unfolds, I continue to test additional risk factor models using measures for volume of international trade, hospital beds/physicians per capita, quality of health care system, availability of affordable health care, demographic characteristics, income inequality, average climate, as well other variables. But so far, in every model I’ve tested, national wealth (per capita), tourism levels, and a nation’s previous experience with communicable diseases consistently maintained their statistical significance.

Of course, COVID-19 is an evolving crisis. These numbers will change over time and many of the countries not currently experiencing high numbers of COVID-19 cases (such as African and South American countries) may see their numbers rise dramatically — thereby, changing the model estimates.

In the meantime, it does appear national levels of wealth, tourism and inexperience with communicable diseases are significant upward drivers in the spread of COVID-19 worldwide.

Could it be that economic neoliberalism and globalization render us increasingly prone to these types of pandemics? Will viruses like the coronavirus become one of the recurring costs associated with the current international economic order?

The most likely answer is Yes.

_________________________________________________________________

Personal Thoughts on COVID-19

I once thought epidemics and pandemics were generally restricted to African countries and places where people eat monkeys and bats.

“I’ll just get a flu shot,” I would say to myself.

Its a callousness built by time and experience.

I lived through the Hong Kong flu of 1968–69, the Swine Flu of 1976, and the H1N1 Flu of 2009 — which is to say, I have no real memory of those epidemics. None of them impacted me personally. I vaguely recall getting in line at a nearby elementary school to get the Swine Flu vaccine in 1976 and being mad at my parents because I was missing an episode of Welcome Back, Kotter.

First world problems.

That has all changed with COVID-19 (which is caused by the virus 2019-nCoV, otherwise known as the coronavirus).

As of 12 March, there are 127,749 confirmed cases of COVID-19, resulting in 4,717 deaths worldwide. Those numbers will go up a lot before this pandemic ends.

According to infectious disease expert Dr. Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) at the University of Minnesota, told podcaster Joe Rogan that COVID-19 could be “at least 10 to 15 times worse than the worst seasonal flu (in terms of fatalities).”

“We can conservatively estimate that this could require 48 million hospitalizations, 96 million cases actually occurring, and over 480 thousand deaths (worldwide),” says Dr. Osterholm.

A conservative estimate.

For me, the overwhelming emotion right now is that of powerlessness. Beyond the obvious but impractical response — not leaving the house until this is over — I don’t know what else to do to protect my family and myself. It feels like a game of Russian roulette on a global scale. We could do everything possible — wear a mask and gloves, avoid crowds, etc. — and still get the virus.

As a statistician, I bring a clinical, dispassionate understanding of random chance and relative risk to this crisis. As a husband and parent, I am staggered by a slow-burning anxiety these days.

I just want this to be over.

- K.R.K.

Comments and suggestions can be sent to: kroeger98@yahoo.com

_________________________________________________________________

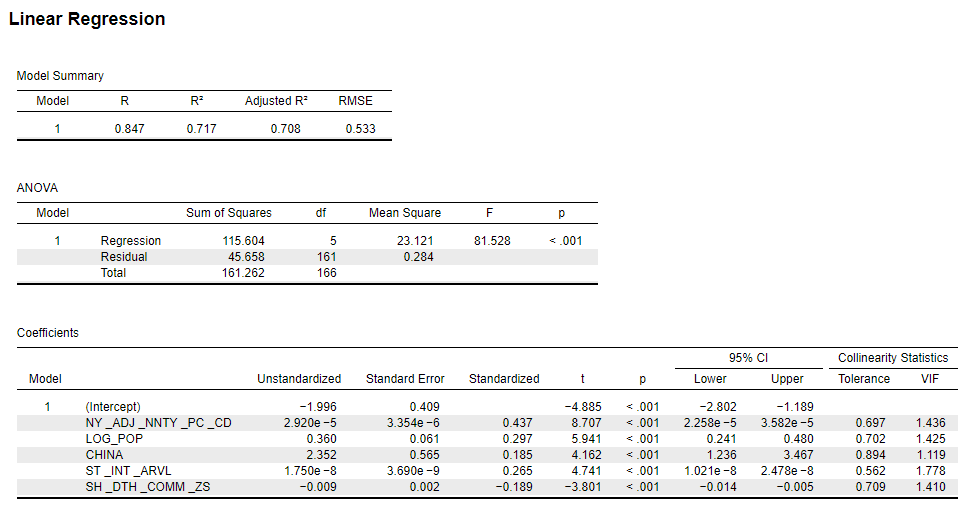

Appendix: A Regression Model of Confirmed COVID-19 Cases Worldwide (as of 10 March 2020)

Variables

Dependent Variable (Source: WHO): Number of confirmed COVID-19 cases as of 10 March 2020 (log transformed)

Independent Variables (Source: World Bank):

NY_ADJ_NNTY_PC_CD = Adjusted net nat’l income per capita (current US$)

LOG_POP = Country’s total populaton (log transformed)

CHINA = Indicator variable (1 = China; 0 = all other countries)

SI_INT_ARVL = International tourism, number of arrivals

SH_DTH_COMM_ZS = Cause of death, by communicable diseases and maternal, prenatal and nutrition conditions (% of all deaths)

More detail on these independent variables can be found in the World Bank’s data catalog at: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators

Model Fit

Overall, the model explained 71 percent of the variance in confirmed COVID-19 cases on a national level.

Other Methodological Issues:

I should note that I used a linear regression model in this analysis. However, a Poisson model is the appropriate technique to use with count-data (such as the number of COVID-19 cases). I chose to report the linear regression model, in part, because linear regression is generally more familiar to a larger segment of readers. Nonetheless, I did run the same model using Poisson regression in SPSS and found no substantive differences in the results.