[Headline photo: Judit Polgár, a chess super grandmaster and generally considered the greatest female chess player ever (Photo by Tímea Jaksa)]

By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; December 8, 2020)

One the greatest joys I’ve had as a parent is teaching my children how to play chess.

And the most bittersweet moment in that effort is the day (and match) when they beat you and you didn’t let them.

I had that moment during the Thanksgiving weekend with my teenage son when, in a contest where early on I sacrificed a knight to take his queen (and maintained that advantage for the remainder of the contest), I became too aggressive and left my king vulnerable. As I realized the mistake, it was two moves too late. He pounced and mercilessly ended the match.

He didn’t brag. No teasing. Not even a firm handshake. He checkmated me, grabbed a bowl of blueberries out of the fridge, and coolly went to the family room to play Call of Duty with his friends on his Xbox.

I was left with an odd feeling, common among parents and teachers, I suspect. A feeling of immense pride, even as my ego was genuinely bruised.

That is the nature of chess — a game that is both simple and infinitely complex, and offers no prospect of luck for the casual or out-of-practice player. With every move there are only three possibilities: You can make a good decision, a bad decision, or maintain the status quo.

For this, I love and hate chess.

Saying ‘Chess has a gender problem’ is an understatement

My father taught me chess, as his father taught him.

Growing up in the 70s, I had a picture of grandmaster legend Bobby Fischer pasted on my bedroom door, whose defeat of Boris Spassky for the 1972 world chess title ranks with the U.S. hockey team’s 1980 “Miracle on Ice” as one of this country’s defining Cold War “sports” victories over the Soviet Union. That is not an exaggeration.

In part because of Fischer’s triumph, I played chess with my childhood friends more often than any other game, save perhaps basketball and touch football.

But despite chess being prominent in my youth, I have no memories of playing chess with members of the opposite sex. My mom? Bridge was her game of choice. The girls in my neighborhood and school? I cannot recall even one match with them. Granted, between the 5th and 11th grades, I didn’t interact with girls much for any reason. And when I did later in high school, by then my chess playing was mostly on hold until graduate school, except for the occasional holiday matches with my father and brothers.

Any study on the sociohistorical determinants of gender-based selection bias should consider chess an archetype of this phenomenon.

The aforementioned chess prodigy, Bobby Fischer, infamously said of women: “They’re all weak, all women. They’re stupid compared to men. They shouldn’t play chess, you know. They’re like beginners. They lose every single game against a man.”

Any pretense that grandmaster chess players must, by means of their chessboard skills, also be smart about everything else, is easily dispensed by referencing the words that would frequently come out of Fischer’s mouth when he was alive.

Radio personality Howard Stern once observed that many of the most talented musicians he’s interviewed often lack the ability (or confidence) to talk about anything else except music (and perhaps sex and drugs): “You can’t become that good at something without sacrificing your knowledge in other things.”

That may be one of the great sacrifices grandmaster chess players also make. As evidenced by his known comments on women and chess, Fischer is ill-informed on gender science. Even some contemporary chess greats, such as Garry Kasparov and Nigel Short, have uttered verbal nonsense on the topic.

Writer Katerina Bryant recently reflected on the persistent ignorance within the chess world about gender: “Many of us mistake chess players for the world’s best thinkers, but laying out a champion’s words on the table make the picture seem much more fractured. It’s a fallacy that someone can’t be both informed and ignorant.”

Why we are watching the “The Queen’s Gambit”

Over the Thanksgiving holiday, the intersection in time of losing to my son at chess and the release of Netflix’ new series, The Queen’s Gambit, seemed like an act of providence. The two events reignited my interest in chess and launched a personal investigation into the game’s persistent and overwhelming gender bias.

Of the current 80 highest-rated chess grandmasters, all are men. The highest-rated woman is China’s Hou Yifan (#82).

That ain’t random chance. Something is fundamentally wrong with how the game recruits and develops young talent. The Queen’s Gambit, a fictional account of a young American woman’s rise in the chess world during the 1950s and 60s, speaks directly to that malfunction. While the show mostly focuses on drug addiction, dependency, and emotional alienation, I believe its core appeal is in how it addresses endemic sexism — in this case, the gender bias of competitive chess.

For those that don’t know, The Queen’s Gambit is a 7-part series (currently streaming on Netflix) about Beth Harmon, an orphaned chess prodigy from Kentucky who rises to become one of the world’s greatest chess player while struggling with emotional problems and drug and alcohol dependency. Beth is a brilliant, intuitive chess player…and a total mess.

The Queen’s Gambit is more fun to watch than it sounds. My favorite scene is in Episode 1 when, as a young girl, she plays a simultaneous exhibition against an entire high school chess club and beats them — all boys, of course — easily.

The TV series not only perfectly aligns with the current political mood, its gender bias message is not heavy-handed and is easily digestible. It is fast food feminism for today’s cable news feminists.

Aside from the touching characterization of Mr. Shaibel, the janitor at Beth’s orphanage who introduces her to chess, almost every other man in The Queen’s Gambit is either sexist, a substance abuser, arrogant, or emotionally stunted. What saves The Queen’s Gambit’s cookie-cutter politics from becoming overly turgid and preachy, however, is that Beth isn’t much better, or at least not until the end. Anya Taylor-Joy, the actress who plays Beth, is brilliant throughout the series and alone makes the show’s seven hours running time worth the personal investment.

But beyond the show’s high-end acting and production values, its hard not to enjoy a television show about a goodhearted but dysfunctional protagonist (i.e., substance addicted) who must interact with other dysfunctional people in an equally dysfunctional time?

The audience gets all of that from The Queen’s Gambit, along with a thankfully minor but clunky anti-evangelical Christian, anti-anti-Communism side story.

It is the perfect formula for getting love from the critics and attracting an audience, and the reviews and ratings for The Queen’s Gambit prove the point:

“(The Queen’s Gambit) is the sort of delicate prestige television that Netflix should be producing more often.” – Richard Lawson, Vanity Fair

“Just as you feel a familiar dynamic forming, in which a talented woman ends up intimidating her suitors, The Queen’s Gambit swerves; it’s probably no coincidence that a story about chess thrives on confounding audience expectations.” – Judy Berman, TIME Magazine

The audiences have lined up accordingly. In its first three weeks after release (from October 23 to November 8), Nielsen estimates that The Queen’s Gambit garnered almost 3.8 billion viewing minutes in the U.S. alone.

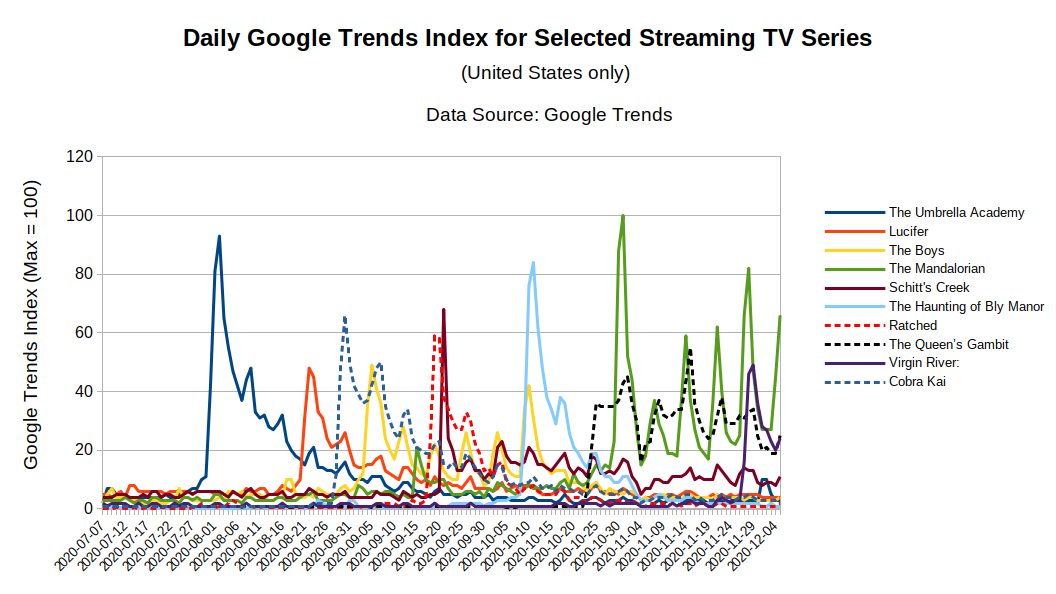

As the streaming TV ratings methodologies are still in their relative infancy, I prefer to look at Google search trends when comparing media programs and properties. In my own research, I have found that Google searches are highly correlated with Nielsen’s streaming TV ratings (ranging between a Pearson correlation of 0.7 and 0.9 from week-to-week).

Figure 1 shows a selection of the most popular streaming TV shows in 2020 and their relative number of Google searches (in the U.S.) from July to early December [The Queen’s Gambit is the dashed black line.]. While The Queen’s Gambit hasn’t had the peak number of searches as some other shows (The Umbrella Academy, Schitt’s Creek, and The Mandalorian), it has sustained a high level of searching over a longer period of time. Over a 5-week period, only The Mandalorian has had a cumulative Google Trends Index higher than The Queen’s Gambit (1,231 versus 1,150, respectively). The next highest is The Umbrella Academy at 1,030.

Figure 1: Google Searches for Selected Streaming TV Shows in 2020

Whatever the core reason for the popularity of The Queen’s Gambit, there is no denying that the show has attracted an unprecedented mass audience for a streaming TV series.

It makes me think Netflix might consider making more than seven episodes.

My one big annoyance with “The Queen’s Gambit”

Mark Twain once said of fiction: “Truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; truth isn’t.”

While I appreciate Twain’s sentiment — fiction should not be too restrained by truth — he clearly never had to explain to his teenage son that fire-breathing dragons did not exist in the Middle Ages, despite what Game of Thrones suggests. I fear The Queen’s Gambit will launch of generation of people who think an American woman competed internationally in chess in the 1960s and thereby diminish the much more profound accomplishments of an actual female chess prodigy, Judit Polgár, arguably the greatest female chess player of all time and who famously refused to compete in women-only chess tournaments.

While her achievements would occur two decades after Beth Harmon’s fictional rise, Polgár, a 44-year-old Hungarian, fought the real battle and offers the more substantive and entertaining story, in my opinion. It would be like Hollywood making a movie about a fictional female law professor defeating institutional sexism and rising to the Supreme Court in the 1960s, when the true story of Ruth Bader Ginsburg already exists.

Granted, Walter Tevis’ book upon which The Queen’s Gambit is based was published in 1983, before Polgár was competing internationally, but for someone who followed Polgár’s career, The Queen’s Gambit‘s inspirational tale rings a bit hollow.

No American woman was competing at the highest levels of chess during The Queen’s Gambit time frame of the 1950s and 60s. In stark contrast, Polgár actually did that from 1990 to 2014, achieving a peak rating of 2735 in 2005 — which put her at #8 in the world at the time and would place her at #20 in the world today.

Perhaps only chess geeks understand how rare such an accomplishment is in chess, regardless of gender.

Polgár, at the age of 12, was the youngest chess player ever, male or female, to become ranked in the World Chess Federations’s top 100 (she was ranked #55) and became a Grandmaster at 15, breaking the youngest-ever record previously held by former World Champion Bobby Fischer.

The list of current or former world champions Polgár has defeated in either rapid or classical chess is mind-blowing: Magnus Carlsen (the highest rated player of all time), Anatoly Karpov, Garry Kasparov, Vladimir Kramnik, Boris Spassky, Vasily Smyslov, Veselin Topalov, Viswanathan Anand, Ruslan Ponomariov, Alexander Khalifman, and Rustam Kasimdzhanov. [I’m geeking out just reading these names.]

And most amazing of all — Polgár may not be the best chess player in her family.

Still, I want to be clear: I loved the The Queen’s Gambit. I don’t sit up at 3 a.m. watching Netflix on my iPhone unless I have a good reason — such as watching Czech porn. I merely offer a piece of criticism so that some poor sap 20 years from now doesn’t think The Queen’s Gambit is based on a true story. It most certainly isn’t. It is a pure Hollywood-processed work of fiction.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: nuqum@protonmail.com