By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; August 18, 2020)

The data used in this essay can be found here: GITHUB

“The lady doth protest too much, methinks”

— Queen Gertrude, Act III, Scene II of Hamlet

In the past few weeks, New York Governor Andrew M. Cuomo’s rhetoric attacking the Trump administration’s response to the coronavirus has noticeably escalated.

“This was a colossal blunder, how this COVID was handled by this government,” Cuomo said in an August 3rd press conference. “The worst government blunder in modern history.”

Not stopping there, Cuomo compared the coronavirus pandemic to the Vietnam War (not a bad comparison in my opinion) and capped off his partisan broadside with a gasping “shame on all of you” directed at the entire Trump administration.

Even the normally Cuomo-deferential New York media couldn’t help but notice Cuomo’s pointed hyperbole coincided with a growing examination by the New York state legislature (and a small number of journalists) of Cuomo’s decision early in the pandemic to push for the transfer of elderly COVID-19 patients in hospitals to nursing home facilities.

In other words, New York state officials deliberately inserted #coronavirus patients into locations where the people most vulnerable to the virus (the elderly) were concentrated.

What could go wrong?

According to New York’s Department of Health, over 6,000 New York coronavirus deaths have occurred in nursing homes. But it is likely this “official” number is a significant undercount.

The heat on Cuomo has in fact turned up so significantly that the state’s Health Department has already “exonerated” the Cuomo administration of any blame.

It’s good to have friends in high places.

David L. Reich MD, President and COO of The Mount Sinai Hospital and Mr. Michael Dowling, CEO, Northwell Health led a quantitative investigation into any potential link between the transfer of COVID-19 patents into nursing home facilities and nursing home coronavirus deaths.

In their report, they concluded COVID-19 was introduced into nursing homes by infected staff, not by patient transfers from hospitals. They ruled out the transfer policy as the culprit for the following reasons:

“A causal link between the admission policy and infections/fatalities would be supported through a direct link in timing between the two, meaning that if admission of patients into nursing homes caused infection — and by extension mortality — the time interval between the admission and mortality curves would be consistent with the expected interval between infection and death. However, the peak date COVID-positive residents entered nursing homes occurred on April 14, 2020, a week after peak mortality in New York’s nursing homes occurred on April 8, 2020. If admissions were driving fatalities, the order of the peak fatalities and peak admissions would have been reversed.”

So there you go, the problem wasn’t the Governor Cuomo’s coronavirus policies, it was the substandard COVID-19 mitigation efforts of New York’s nursing home facilities. It’s a good thing Governor Cuomo and the state legislature smuggled a provision into the state’s budget bill in late March that increased legal protections for nursing home operators from wrongful death lawsuits related to the coronavirus.

Case closed. Yes?

Hardly.

Dr. Reich’s and Mr. Dowling’s conclusion that the hospital-to-nursing home transfer policy (H2NH) was not responsible for New York’s large number of nursing home based coronavirus deaths is built on a shaky foundation.

As reported by the Associated Press, New York’s coronavirus death toll in nursing homes is very likely an undercount of the true number of COVID-19-related deaths. According to the AP story, state officials adopted a policy that classifies coronavirus deaths as being nursing home-related only if the residents dies on nursing home property. Based on this policy, nursing home residents that die at a hospital are not considered nursing home deaths. According to state officials, the reason for this counting procedure is that it avoids double-counting coronavirus deaths. Certainly a legitimate reason.

However, using New York Department of Health data on vacant nursing home beds, The Hill’s Zach Budryk estimates that 13,000 New York nursing home residents have died from the coronavirus, over twice the official 6,000 number.

Through no fault of Dr. Reich or Mr. Dowling, their statistical analysis of New York nursing home deaths uses faulty data. Nonetheless, their finding that nursing home staff workers brought the virus into nursing homes, not hospital transfers, still begs the question: Why would the state of New York move their most vulnerable coronavirus patients from hospitals into nursing homes, known early in the pandemic to be susceptible to cluster outbreaks, such as a widely reported example in Washington state in March?

Even if their Granger-like causality test didn’t find a rise in nursing home transfers from hospitals was followed by a rise in nursing home coronavirus deaths, Dr. Reich and Mr. Dowling offer no defense of the H2NH policy.

Nursing Home Immunity and the Hospital-to-Nursing Home Transfer Policy

Governor Cuomo is right about one thing, he just failed to name one of the most culpable policymakers — himself. He, along with a handful of other governors, probably made a colossal blunder very early in the pandemic.

The unfortunate interaction of two specific coronavirus policies implemented by a small number of U.S. states (CT, MA, MI, NJ, NY, RI) may have resulted in an additional 27,500 deaths, as of August 13. That translates into about 15 percent more coronavirus deaths than should have occurred given other factors known to correlate with the relative number of state-level coronavirus deaths.

What were the policies?

(1) Granting enhanced immunity to nursing home operators from prosecution over coronavirus-related nursing home deaths (immunity protections), and

(2) Financially enticing nursing home operators to take on elderly coronavirus patients who had been occupying hospital beds (H2NH).

As of today, 19 states have some type of enhanced legal immunity for nursing home operators during the coronavirus pandemic. Those states include: Alabama, Arizona, Connecticut, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Kansas, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Utah, Vermont, Virginia and Wisconsin. According to the AARP, these laws “differ slightly from state to state, but most shield facilities from civil claims only, and just for the duration of the COVID-19 emergency.”

As for transferring COVID-19 patients to nursing homes, my own research has found only six states that have immunity protections for nursing home operators and have actively provided financial incentives to nursing home operators to take these patients (Connecticut, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island).

Superficially, both state-level policies sound morally horrendous: Why grant enhanced legal protections to nursing home operators — an economic group that is not exactly suffering financially these days? And why transfer elderly coronavirus patients from hospitals to nursing homes?

But both policies are predicated on sound reasoning, particularly at the beginning of a pandemic in which experts don’t know the lethality or morbidity rates of a fast-spreading virus. With mortality rates of 4 percent floating around in the media-fueled panic in March (the true number is probably around 0.65 percent, according to the latest CDC numbers), it would seem rational for governors to consider any policy configured to conserve hospital beds.

Cuomo, like all governors, did not know in early March whether the coronavirus might overwhelm the state’s hospital and ICU beds in a matter of weeks or days. Since nursing homes can provide near-hospital level care, it made sense to some states to use excess bed capacities in nursing homes to augment limited bed capacities in hospitals. If that policy required additional protections for nursing home operators, in the end, it would be worth it if the two policies together saved lives.

It was not a crazy set of policies to consider — but it was a tragic set of policies to implement.

For the six states that implemented the immunity protections for nursing homes and the policy of incentivizing nursing homes to take hospital transfers, the outcome is measured in human lives.

According to my analysis below, around 22,500 additional coronavirus deaths have occurred in the U.S. due to Connecticut, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island adopting the combination of nursing home operator immunity enhancements and the attendant transfer of elderly coronavirus patients from hospitals to nursing homes.

The Analysis

Policy analysis requires as much piety as it does statistics. It creates mythical worlds — What would be different if this policy did or didn’t exist? — and compares that result to the actual world.

My first pious decision is to ignore existing data provided by most U.S. states on the number of coronavirus deaths in nursing homes — as the evidence suggests those numbers are not consistent across states — and, instead,

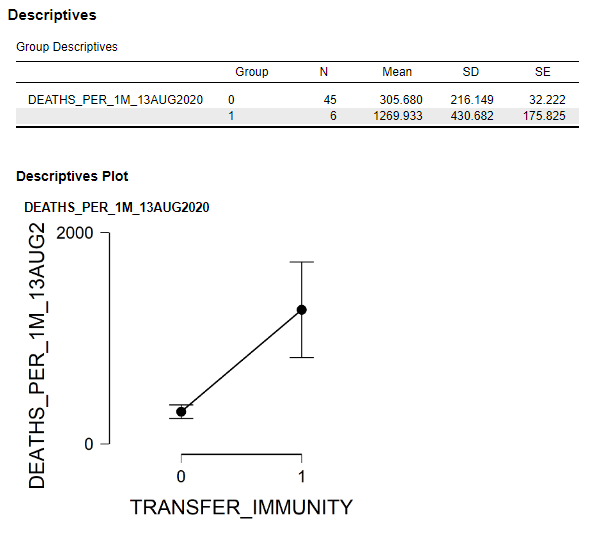

In that spirit, here is a simple comparison of the six dual policy U.S. states that had both policies — the enhanced immunity for nursing homes and the transfer of COVID-19 patients from hospitals to nursing homes — with the 44 states (plus the District of Columbia) that did not. Figure 1 shows the differences in the mean number of coronavirus deaths per 1 million people for those two groups of states.

Figure 1: Comparison of mean coronavirus deaths per 1 million people between U.S. states with both immunity and nursing home transfer policies and U.S. states without the combined policies.

As of August 13, the six dual policy states had a mean number of coronavirus deaths per 1 million people of 1270, compared to only 306 for the other states. This difference is statistically significant.

Why such a big difference?

The answer may be that the combination of the immunity protections and H2NH policies adopted by Connecticut, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island were horrendously bad policy decisions. But other factors could also explain those differences such as population density, percentage of the population without health insurance, the state’s relative economic wealth, and other policy decisions.

[Though not addressed in the analysis here, there is also the possibility the coronavirus that has ravaged the U.S. northeast is fundamentally different from the coronavirus hitting other parts of the U.S.]

I further analyzed the U.S. state-level data (including the District of Columbia) using a mediation analysis (see Figure 2) which controls for the other factors that may explain why Connecticut, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island have had significantly more deaths per capita (as of August 13).

In this analysis, where the number of deaths per capita is the outcome variable, the number of coronavirus cases per capita is the mediator variable through which the independent effects of (a) the number of tests per capita, (b) population density, © GDP per capita, (d) percent of state population without health insurance, (e) the presence of state- or local-level travel restrictions, and © the dual policy of immunity protections and H2NH are estimated.

Figure 2: Mediation model of coronavirus deaths per capita in the 50 U.S. states plus the D.C. (Data source: Johns Hopkins Univ. [CSSE]; data through August 13, 2020)

The focus of this essay is on the effects of the dual policy of immunity protections and the transfer of elderly coronavirus patients from hospitals to nursing homes. In the model estimates (Figure 2), this policy is found to be significantly associated with differences in state-level coronavirus deaths per capita, all else equal. Though I won’t discuss in detail here, other variables found to be significant predictors of coronavirus deaths were (in order magnitude): (1) a state’s population density, (2) the presence of state- or local-level travel restrictions, (3) percent of the state’s population without health insurance, and (4) the number of coronavirus tests per capita.

Using the parameter estimates from the mediation model in Figure 2, two predicted values for each state were calculated: one with the effects of the dual policy (immunity protection and H2NH) included, and one without the effects of the dual policy. Figure 3 compares these predicated values with the actual number of coronavirus deaths per capita for the six states that adopted the dual policy.

Figure 3: The Actual and Predicted Number of Coronavirus Deaths per Capita with and without the Effects of the Dual Policy (CT, MA, MI, NJ, NY, and RI)

According to the estimates in Figure 3, an additional 22,531 coronavirus deaths may have occurred in CT, MA, MI, NJ, NY and RI due to the dual policy of immunity protections and transfer of elderly coronavirus patients from hospitals to nursing homes. New York alone may have already witnessed 9.417 excess deaths due to the dual policy — more than the 6,000+ nursing home deaths currently being reported by the New York Health Department.

If accurate, these are shocking numbers for the six dual policy states. Shocking enough that, at a minimum, further investigation and more sophisticated statistical modeling is warranted to fully understand the potential damage done by the nursing home operator immunity and H2NH policies.

Final Thoughts

Not only in the U.S. were these policies implemented during the current pandemic, Scotland (U.K.) adopted similar policies with perhaps equally dreadful consequences.

How could such policies be adopted so quickly without more public and scientific input on their rationality? Governor Cuomo and other prominent Democrats enjoy lecturing us on “believing the science.” But where was the science on these two policies?

No doubt, the Republicans will point out that the six dual policy states are all Democrat-dominated states and five are led by Democrat governors (the exception being Massachusetts).

Why would Democrats be more inclined to protect nursing home operators and use nursing home beds to relieve stress on a state’s hospital system?

Could it be money?

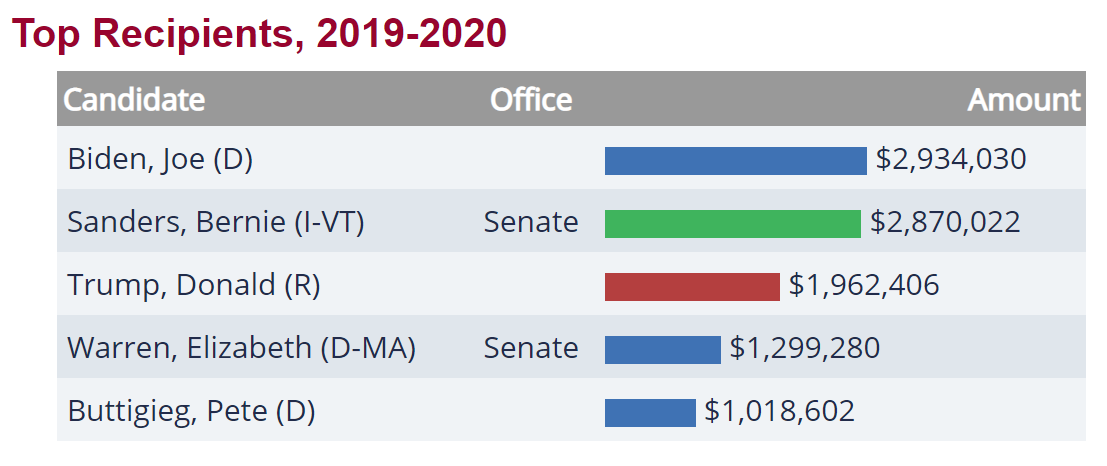

Figure 4: Campaign contributions from hospital and nursing home related donors by political party (Source: OpenSecrets.org)

Figure 5: Leading recipients of campaign contributions from hospital and nursing home related interests during the 2019–2020 election cycle (Source: OpenSecrets.org)

For the past three election cycles, the Democrats have received the most campaign contributions from hospital and nursing home donors (see Figure 4). In the current election cycle (2019–2020), the Democrats have received almost twice as much money as the Republicans from hospital and nursing home interests ($24 million versus $12 million, respectively). And it particularly pains me to note that Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders trails only Joe Biden in hospital and nursing home donor money.

Admittedly, this is circumstantial evidence of undue influence on state and federal coronavirus policies by the hospital and nursing home lobbies during this pandemic, but my deep-seated cynicism has suspicions that the scientific community and the American people in general were not at the table when these policies were decided.

Its just a hunch.

- K.R.K.

The data used in this essay can be found here: GITHUB

Please send comments to: kroeger98@yahoo.com

or DM me on Twitter at: @KRobertKroeger1

Even the normally Cuomo-deferential New York media couldn’t help but notice Cuomo’s pointed hyperbole coincided with a growing examination by the New York state legislature (and a small number of journalists) of Cuomo’s decision early in the pandemic to push for the transfer of elderly COVID-19 patients in hospitals to nursing home facilities.

In other words, New York state officials deliberately inserted #coronavirus patients into locations where the people most vulnerable to the virus (the elderly) were concentrated.

What could go wrong?

According to New York’s Department of Health, over 6,000 New York coronavirus deaths have occurred in nursing homes. But it is likely this “official” number is a significant undercount.

The heat on Cuomo has in fact turned up so significantly that the state’s Health Department has already “exonerated” the Cuomo administration of any blame.

It’s good to have friends in high places.

David L. Reich MD, President and COO of The Mount Sinai Hospital and Mr. Michael Dowling, CEO, Northwell Health led a quantitative investigation into any potential link between the transfer of COVID-19 patents into nursing home facilities and nursing home coronavirus deaths.

In their report, they concluded COVID-19 was introduced into nursing homes by infected staff, not by patient transfers from hospitals. They ruled out the transfer policy as the culprit for the following reasons:

“A causal link between the admission policy and infections/fatalities would be supported through a direct link in timing between the two, meaning that if admission of patients into nursing homes caused infection — and by extension mortality — the time interval between the admission and mortality curves would be consistent with the expected interval between infection and death. However, the peak date COVID-positive residents entered nursing homes occurred on April 14, 2020, a week after peak mortality in New York’s nursing homes occurred on April 8, 2020. If admissions were driving fatalities, the order of the peak fatalities and peak admissions would have been reversed.”

So there you go, the problem wasn’t the Governor Cuomo’s coronavirus policies, it was the substandard COVID-19 mitigation efforts of New York’s nursing home facilities. It’s a good thing Governor Cuomo and the state legislature smuggled a provision into the state’s budget bill in late March that increased legal protections for nursing home operators from wrongful death lawsuits related to the coronavirus.

Case closed. Yes?

Hardly.

Dr. Reich’s and Mr. Dowling’s conclusion that the hospital-to-nursing home transfer policy (H2NH) was not responsible for New York’s large number of nursing home based coronavirus deaths is built on a shaky foundation.

As reported by the Associated Press, New York’s coronavirus death toll in nursing homes is very likely an undercount of the true number of COVID-19-related deaths. According to the AP story, state officials adopted a policy that classifies coronavirus deaths as being nursing home-related only if the residents dies on nursing home property. Based on this policy, nursing home residents that die at a hospital are not considered nursing home deaths. According to state officials, the reason for this counting procedure is that it avoids double-counting coronavirus deaths. Certainly a legitimate reason.

However, using New York Department of Health data on vacant nursing home beds, The Hill’s Zach Budryk estimates that 13,000 New York nursing home residents have died from the coronavirus, over twice the official 6,000 number.

Through no fault of Dr. Reich or Mr. Dowling, their statistical analysis of New York nursing home deaths uses faulty data. Nonetheless, their finding that nursing home staff workers brought the virus into nursing homes, not hospital transfers, still begs the question: Why would the state of New York move their most vulnerable coronavirus patients from hospitals into nursing homes, known early in the pandemic to be susceptible to cluster outbreaks, such as a widely reported example in Washington state in March?

Even if their Granger-like causality test didn’t find a rise in nursing home transfers from hospitals was followed by a rise in nursing home coronavirus deaths, Dr. Reich and Mr. Dowling offer no defense of the H2NH policy.

Nursing Home Immunity and the Hospital-to-Nursing Home Transfer Policy

Governor Cuomo is right about one thing, he just failed to name one of the most culpable policymakers–himself. He, along with a handful of other governors, probably made a colossal blunder very early in the pandemic.

The unfortunate interaction of two specific coronavirus policies implemented by a small number of U.S. states (CT, MA, MI, NJ, NY, RI) may have resulted in an additional 27,500 deaths, as of August 13. That translates into about 15 percent more coronavirus deaths than should have occurred given other factors known to correlate with the relative number of state-level coronavirus deaths.

What were the policies?

(1) Granting enhanced immunity to nursing home operators from prosecution over coronavirus-related nursing home deaths (immunity protections), and

(2) Financially enticing nursing home operators to take on elderly coronavirus patients who had been occupying hospital beds (H2NH).

As of today, 19 states have some type of enhanced legal immunity for nursing home operators during the coronavirus pandemic. Those states include: Alabama, Arizona, Connecticut, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Kansas, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Utah, Vermont, Virginia and Wisconsin. According to the AARP, these laws “differ slightly from state to state, but most shield facilities from civil claims only, and just for the duration of the COVID-19 emergency.”

As for transferring COVID-19 patients to nursing homes, my own research has found only six states that have immunity protections for nursing home operators and have actively provided financial incentives to nursing home operators to take these patients (Connecticut, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island).

Superficially, both state-level policies sound morally horrendous: Why grant enhanced legal protections to nursing home operators–an economic group that is not exactly suffering financially these days? And why transfer elderly coronavirus patients from hospitals to nursing homes?

But both policies are predicated on sound reasoning, particularly at the beginning of a pandemic in which experts don’t know the lethality or morbidity rates of a fast-spreading virus. With mortality rates of 4 percent floating around in the media-fueled panic in March (the true number is probably around 0.65 percent, according to the latest CDC numbers), it would seem rational for governors to consider any policy configured to conserve hospital beds.

Cuomo, like all governors, did not know in early March whether the coronavirus might overwhelm the state’s hospital and ICU beds in a matter of weeks or days. Since nursing homes can provide near-hospital level care, it made sense to some states to use excess bed capacities in nursing homes to augment limited bed capacities in hospitals. If that policy required additional protections for nursing home operators, in the end, it would be worth it if the two policies together saved lives.

It was not a crazy set of policies to consider–but it was a tragic set of policies to implement.

For the six states that implemented the immunity protections for nursing homes and the policy of incentivizing nursing homes to take hospital transfers, the outcome is measured in human lives.

According to my analysis below, around 22,500 additional coronavirus deaths have occurred in the U.S. due to Connecticut, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island adopting the combination of nursing home operator immunity enhancements and the attendant transfer of elderly coronavirus patients from hospitals to nursing homes.

The Analysis

Policy analysis requires as much piety as it does statistics. It creates mythical worlds–What would be different if this policy did or didn’t exist?–and compares that result to the actual world.

My first pious decision is to ignore existing data provided by most U.S. states on the number of coronavirus deaths in nursing homes–as the evidence suggests those numbers are not consistent across states–and, instead,

In that spirit, here is a simple comparison of the six dual policy U.S. states that had both policies–the enhanced immunity for nursing homes and the transfer of COVID-19 patients from hospitals to nursing homes –with the 44 states (plus the District of Columbia) that did not. Figure 1 shows the differences in the mean number of coronavirus deaths per 1 million people for those two groups of states.

Figure 1: Comparison of mean coronavirus deaths per 1 million people between U.S. states with both immunity and nursing home transfer policies and U.S. states without the combined policies.

As of August 13, the six dual policy states had a mean number of coronavirus deaths per 1 million people of 1270, compared to only 306 for the other states. This difference is statistically significant.

Why such a big difference?

The answer may be that the combination of the immunity protections and H2NH policies adopted by Connecticut, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island were horrendously bad policy decisions. But other factors could also explain those differences such as population density, percentage of the population without health insurance, the state’s relative economic wealth, and other policy decisions.

[Though not addressed in the analysis here, there is also the possibility the coronavirus that has ravaged the U.S. northeast is fundamentally different from the coronavirus hitting other parts of the U.S.]

I further analyzed the U.S. state-level data (including the District of Columbia) using a mediation analysis (see Figure 2) which controls for the other factors that may explain why Connecticut, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island have had significantly more deaths per capita (as of August 13).

In this analysis, where the number of deaths per capita is the outcome variable, the number of coronavirus cases per capita is the mediator variable through which the independent effects of (a) the number of tests per capita, (b) population density, (c) GDP per capita, (d) percent of state population without health insurance, (e) the presence of state- or local-level travel restrictions, and (c) the dual policy of immunity protections and H2NH are estimated.

Figure 2: Mediation model of coronavirus deaths per capita in the 50 U.S. states plus the D.C. (Data source: Johns Hopkins Univ. [CSSE]; data through August 13, 2020)

The focus of this essay is on the effects of the dual policy of immunity protections and the transfer of elderly coronavirus patients from hospitals to nursing homes. In the model estimates (Figure 2), this policy is found to be significantly associated with differences in state-level coronavirus deaths per capita, all else equal. Though I won’t discuss in detail here, other variables found to be significant predictors of coronavirus deaths were (in order magnitude): (1) a state’s population density, (2) the presence of state- or local-level travel restrictions, (3) percent of the state’s population without health insurance, and (4) the number of coronavirus tests per capita.

Using the parameter estimates from the mediation model in Figure 2, two predicted values for each state were calculated: one with the effects of the dual policy (immunity protection and H2NH) included, and one without the effects of the dual policy. Figure 3 compares these predicated values with the actual number of coronavirus deaths per capita for the six states that adopted the dual policy.

Figure 3: The Actual and Predicted Number of Coronavirus Deaths per Capita with and without the Effects of the Dual Policy (CT, MA, MI, NJ, NY, and RI)

According to the estimates in Figure 3, an additional 22,531 coronavirus deaths may have occurred in CT, MA, MI, NJ, NY and RI due to the dual policy of immunity protections and transfer of elderly coronavirus patients from hospitals to nursing homes. New York alone may have already witnessed 9.417 excess deaths due to the dual policy–more than the 6,000+ nursing home deaths currently being reported by the New York Health Department.

If accurate, these are shocking numbers for the six dual policy states. Shocking enough that, at a minimum, further investigation and more sophisticated statistical modeling is warranted to fully understand the potential damage done by the nursing home operator immunity and H2NH policies.

Final Thoughts

It was not just in the U.S. where these policies were implemented during the current pandemic. Scotland (U.K.) adopted similar policies with perhaps equally dreadful consequences.

How could such policies be adopted so quickly without more public and scientific input on their rationality? Governor Cuomo and other prominent Democrats enjoy lecturing us on “believing the science.” But where was the science on these two policies?

No doubt, the Republicans will point out that the six dual policy states are all Democrat-dominated states and five are led by Democrat governors (the exception being Massachusetts).

Why would Democrats be more inclined to protect nursing home operators and use nursing home beds to relieve stress on a state’s hospital system?

Could it be money?

Figure 4: Campaign contributions from hospital and nursing home related donors by political party (Source: OpenSecrets.org)

Figure 5: Leading recipients of campaign contributions from hospital and nursing home related interests during the 2019-2020 election cycle (Source: OpenSecrets.org)

For the past three election cycles, the Democrats have received the most campaign contributions from hospital and nursing home donors (see Figure 4). In the current election cycle (2019-2020), the Democrats have received almost twice as much money as the Republicans from hospital and nursing home interests ($24 million versus $12 million, respectively). And it particularly pains me to note that Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders trails only Joe Biden in hospital and nursing home donor money.

Admittedly, this is circumstantial evidence of undue influence on state and federal coronavirus policies by the hospital and nursing home lobbies during this pandemic, but my deep-seated cynicism has suspicions that the scientific community and the American people in general were not at the table when these policies were decided.

Its just a hunch.

- K.R.K.

Please send comments to: kroeger98@yahoo.com

or DM me on Twitter at: @KRobertKroeger1

The data used in this essay can be found here: GITHUB