By Kent R. Kroeger (October 9, 2018; Source: NuQum.com)

This essay was originally published on October 5th. Since then, a Saudi journalist has disappeared in Turkey and a Bulgarian TV journalist has been killed.

According to sources speaking to The Washington Post, the Turkish government believes Saudi Arabian journalist Jamal Khashoggi was “killed in the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul last week by a Saudi team sent specifically for the murder.” The Post’s sources offered no evidence to support their account of events.

Khashoggi, missing since October 2nd, has been an open critic of the current Saudi regime, led by King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud and his son, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

“The humble man I knew, who disappeared from the consulate in Istanbul, saw it as his duty to stand up for ordinary Saudis,” says fellow journalist and friend of Khashoggi, David Hearst.

“Again a courageous journalist falls in the fight for truth and against corruption,” Frans Timmermans, vice president of the European Commission, said Monday in Brussels.

In the other incident, 30-year-old TV journalist Viktoria Marinova was found dead on October 6th in a park in Ruse, Bulgaria.

Marinova was a director of TVN, a TV station in Ruse, Bulgaria and a TV presenter for two investigative news programs, one of which, Detector, recently featured two investigative journalists reporting on suspected fraud involving European Union funds.

Her final TV appearance was on Sept. 30.

Though Bulgarian authorities do not know yet if there is a connection between Marinova’s death and her work as a journalist, many European journalists are concerned as she is the third journalist to be killed in Europe in the past year. The other two murdered journalists were Jan Kuciak in Slovakia and Daphne Caruana Galizia in Malta.

These deaths add to a growing concern among European journalists that their profession is being targeted by power elites and criminal elements threatened by investigative journalism.

Original essay (published October 5, 2018):

In late August, an anti-immigration rally jn Chemnitz, Germany provided vivid evidence of the far right’s growing popularity, the crowd’s anger directed mainly at Chancellor Angela Merkel and her 2015 decision to allow into the country more than 1 million refugees fleeing civil war and violence in the Middle East.

In Germany, the anti-immigration sentiment has been accompanied by a rise in violence attacks on journalists, according to Reporters Without Borders(RSF), who reports “after reaching a peak of 39 attacks against journalists in 2015, this figure dropped to below 20 in 2016 and 2017.” However, in 2018, such violent attacks are already higher than in 2016 or 2017.

RSF also reports this trend is growing worldwide.

Source: ruptly.tv

According to RSF, 70 journalists, including citizen journalists and media assistants, have been killed so far in 2018, and is on pace to exceed 90 deaths by year’s end. In addition, 316 journalists are currently imprisoned, including two Reuters journalists who were recently sentenced by a Myanmar judge to seven years in prison for breaching a law on state secrets.

In comparison, 74 journalists died worldwide in 2017, and 80 died in 2016.

But RSF does more than monitor violence against journalists. Since 2002, the Paris-based group has computed the World Press Freedom Index (WPFI) for over 180 countries. RSF describes the WPFI as follows:

WHAT DOES THE WORLD PRESS FREEDOM INDEX (WPFI) MEASURE?

The Index ranks 180 countries according to the level of freedom available to journalists. It is a snapshot of the media freedom situation based on an evaluation of pluralism, independence of the media, quality of legislative framework and safety of journalists in each country.

HOW THE WPFI IS COMPILED

The degree of freedom available to journalists in 180 countries is determined by pooling the responses of experts to a questionnaire devised by RSF. This qualitative analysis is combined with quantitative data on abuses and acts of violence against journalists during the period evaluated. The criteria used in the questionnaire are pluralism, media independence, media environment and self-censorship, legislative framework, transparency, and the quality of the infrastructure that supports the production of news and information.

RSF’s 2018 report on worldwide press freedom is one of its most pessimistic.

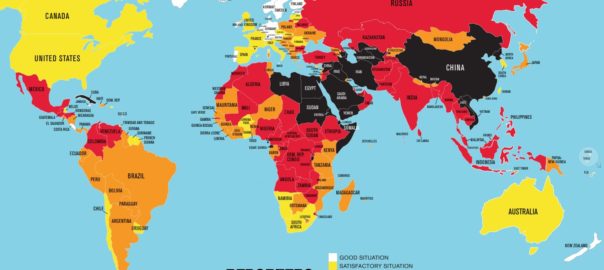

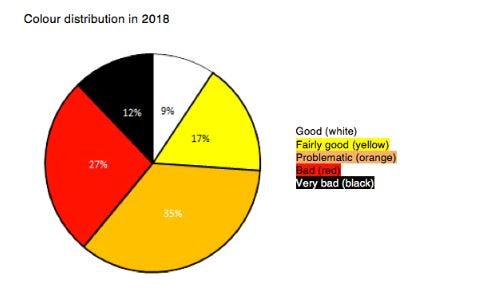

According to the WPFI, in 2018, press freedom in 74 percent of countries is either problematic, bad or very bad (see Figure 1). In 2002, the first year RSF calculated the WPFI, press freedom in only 45 percent of countries was categorized as problematic, bad, or very bad.

Figure 1: Distribution of World Press Freedom Index Scores (2018)

“Hostility towards the media from political leaders is no longer limited to authoritarian countries such as Turkey (ranked 157th out of 180 countries, down two ranks from 2017) and Egypt (161st), where “media-phobia” is now so pronounced that journalists are routinely accused of terrorism and all those who don’t offer loyalty are arbitrarily imprisoned,” reports RSF. “More and more democratically-elected leaders no longer see the media as part of democracy’s essential underpinning, but as an adversary to which they openly display their aversion.”

While citing President Donald Trump as one of the most visible culprits in verbally attacking journalists, RSF’s deepest concern is directed towards younger democracies.

“The line separating verbal violence from physical violence is dissolving. In the Philippines (ranked 133rd, down six from 2017), President Rodrigo Duterte not only constantly insults reporters but has also warned them that they “are not exempted from assassination,” says RSF. “In India (down two ranks to 138th), hate speech targeting journalists is shared and amplified on social networks, often by troll armies in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s pay. In each of these countries, at least four journalists were gunned down in cold blood in the space of a year.”

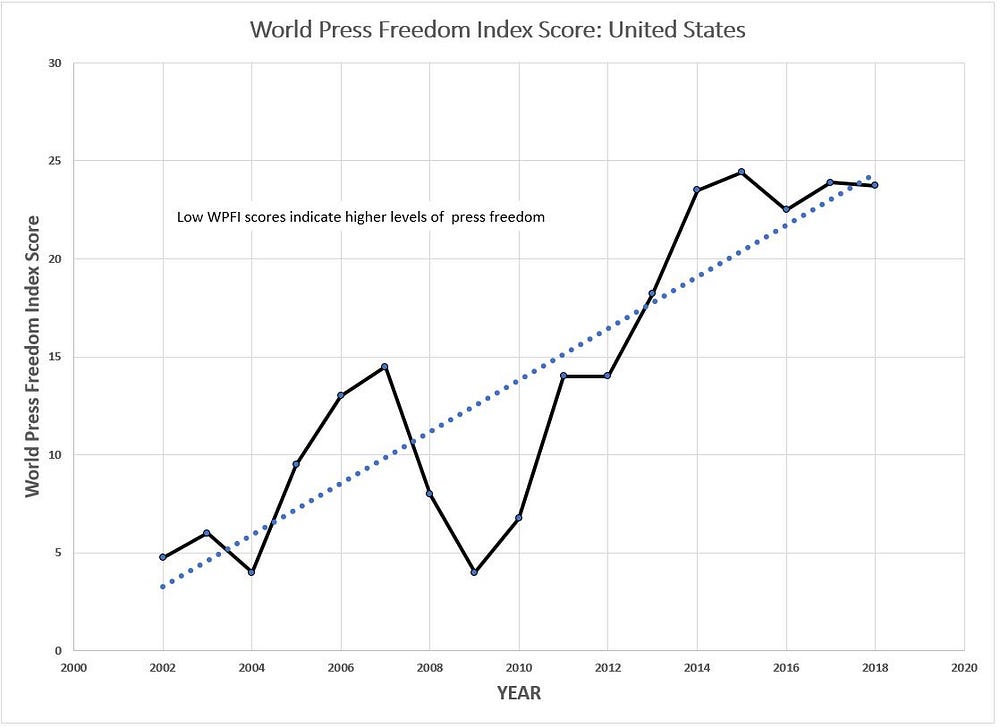

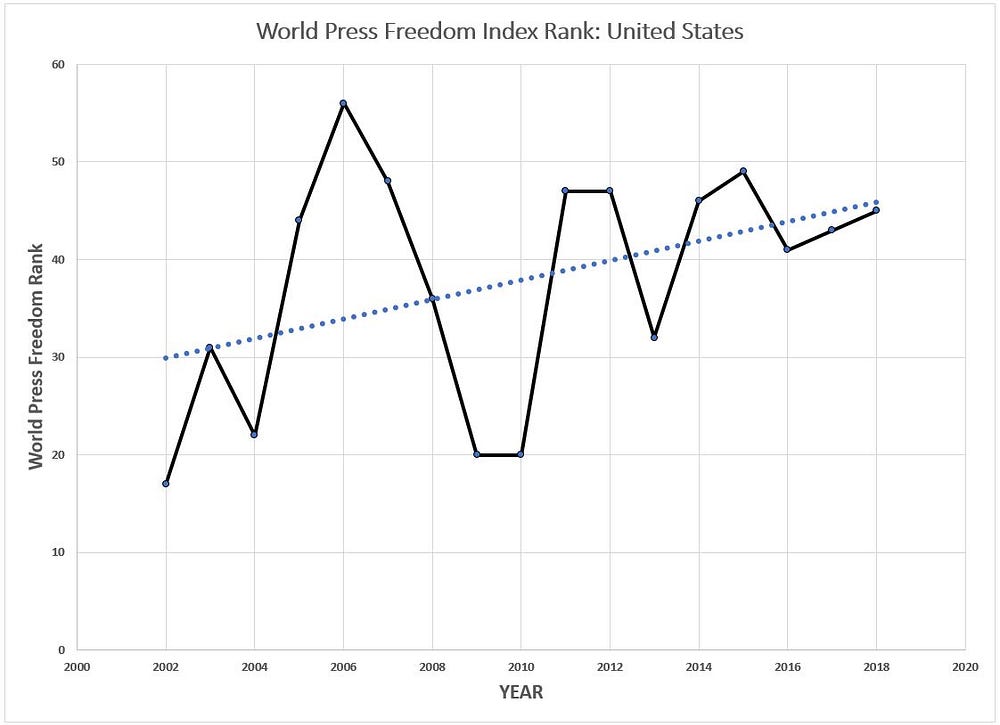

Though physical attacks on U.S. journalists are still rare, the murder of five Maryland journalists last June being a sad exception, press freedom in the U.S. has nonetheless experienced an almost monotonic decline since 2002 (see Figures 2 and 3; high WPFI scores indicate lower levels of press freedom). Only a two-year interlude immediately before and after the 2008 presidential election saw the U.S. score significantly improve.

In 2002, the WPFI score for the U.S. was 4.75 (Rank 17th). Today, the U.S. score is 23.73 (Rank 45th). RSF’s singling out of President Trump as a causal factor in the U.S.’s press freedom decline is misplaced given that the U.S. WPFI score has been relatively flat over the past four years (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: World Press Freedom Index Score for the U.S. (2002–2018)

Figure 3: U.S. Rank on the WPFI (2002–2018)

And RSF is not the only monitoring organization that has found press freedom to be in decline worldwide.

“Only 14 percent of the world’s population live in societies in which there is honest coverage of civic affairs, journalists can work without fear of repression or attack, and state interference is minimal,” according to Freedom House’s Leon Willems and Arch Puddington. “Far too often today, the media present a regime account of developments in which the opposition case is ignored, distorted, or trivialized. And even in more pluralistic environments, news coverage is frequently polarized between competing factions, with no attempt at fairness or accuracy.”

The most troubling aspect of Freedom House’s finding is that even countries within the 14 percent (such as the U.S.) are witnessing an alarming rise in highly-polarized, non-objective journalism. And, in the case of the U.S., journalism is one of the least respected professions, according to the Gallup Poll.

Why has press freedom declined?

The decline in press freedom, worldwide and within the U.S., has many causal antecedents, according to RSF. In explaining the worldwide decline in press freedom in 2014–2015, RSF concluded, “Beset by wars, the growing threat from non-state operatives, violence during demonstrations and the economic crisis, media freedom is in retreat on all five continents.”

In the U.S. context, RSF’s hypotheses are plausible. Since 2002, the U.S. has engaged in two significant wars (Iraq, Afghanistan), both of which have produced mixed results (at best), has led or assisted military actions in Syria, Libya, and Yemen, has experienced a significant economic crisis (2008), and has seen the rise of two large domestic protest movements against an incumbent administration (Tea Party, #Resistance).

Declining media competition may be the biggest threat to journalism

RSF and other media researchers also cite media competition as a significant factor in explaining levels of press freedom. At one extreme is state-controlled media (China, North Korea) where there is no competition and press freedom is severely or completely curtailed. On the other end are pluralistic, democratic societies where media competition is not only present, but facilitated through government policy (Scandinavian countries, Germany New Zealand, Austria).

For the U.S., the media regulatory environment fundamentally changed in 1996 with the U.S. Telecommunications Act.

“There is no doubt the 1996 U. S. Telecommunications Act fueled increasing consolidation across the communication industries. Designed to eliminate barriers to competition, the 1996 Act greatly liberalized ownership limitations for broadcasting and cable companies, allowing companies to acquire more competitors,” according to media economics researchers Alan Albarran and Bozena Mierzejewska. “For example, in the radio industry alone, some 75 different companies operating independently in 1995 were consolidated into just three companies by 2000.”

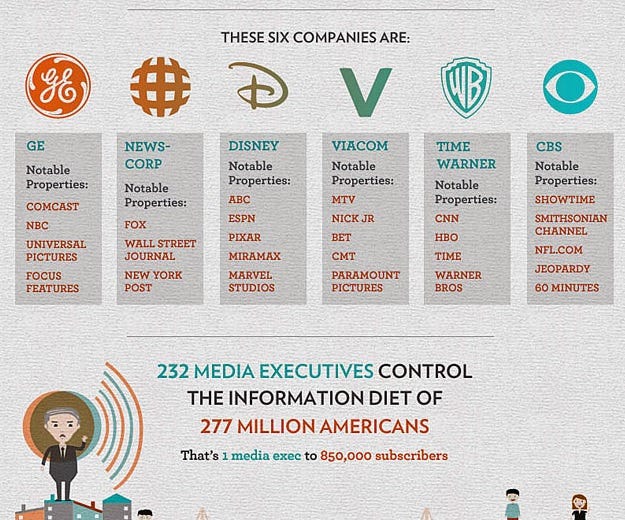

In 1983, 90 percent of US media was controlled by 50 companies. Today, according to Fortune magazine, 90 percent of U.S. media is controlled by just six companies.

Figure 4: Media concentration in the U.S.

How can media consolidation be bad given that the average American has access to over 100 TV channels, not to mention the thousands of internet websites? Shouldn’t the profit-motive impel major corporations to increase the number of information and entertainment choices in order to capture as much of the audience as possible?

That is the argument The New York Time’s Jim Rutenberg made in 2002 as the media consolidation trend was hitting its stride: media mergers create more choice, not less, according to Rutenberg.

Unfortunately, the evidence is not clear at all on that contention. In fact, it appears the opposite is true. Instead of getting real choice, consumers are given the illusion of choice.

“As massive media conglomerates persevere in their quest to monopolize the industry, it is important to realize what this means for alternative viewpoints in media and the already overwhelming effort to hush voices these media giants consider outside the mainstream,” according to Rick Manning, President of Americans for Limited Government. “Differing ideas and perspectives are what make up the very fabric of this great nation, and if we’re not careful with putting too much power in the hands of too few, this could all disappear.”

And when Manning says “alternative viewpoints” he is not talking about the Traditionalist Worker Party getting its own cable TV network. He’s talking about news organizations such as Bloomberg getting squeezed out of the news and information marketplace. Manning is particularly critical of Comcast-NBCU (which owns MSNBC and CNBC).

“Since the Comcast-NBCU merger in 2011, they have proven time and time again that they are not beneath stifling competition or other viewpoints that may not line up with their own. In fact, not only are they not beneath it, there is ample evidence that points to Comcast repeatedly doing so,” contends Manning. “Take Bloomberg TV, for example. Comcast’s conditions stipulated that they place Bloomberg programming next to MSNBC and CNBC, or other competing news channels such as Fox or CNN, in the channel lineup — yet for three years Bloomberg was blocked from the news channel neighborhood and slotted in an unfavorable spot, which negatively affected their viewership.”

With respect to journalism, another potential information-biasing process occurs when large media companies control journalists’ access to audiences through the allocation of broadcast airtime or print space [Whatever happened to Dylan Ratigan and Ed Schultz on MSNBC?]. And instead of providing in-depth information and analysis, today’s news outlets, particularly the cable news networks, bludgeon Americans with lively but mostly content-sparse debate. Why? Because it is profitable. The rule for cable news is this: find your audience, reinforce what they already believe, and for God’s sake don’t make them uncomfortable. Disney, Fox, and Comcast would be delinquent in their duties to shareholders if they did otherwise.

Noam Chomsky, as he often does, offers the most damning critique of cable news: “The smart way to keep people passive and obedient is to strictly limit the spectrum of acceptable opinion, but allow very lively debate within that spectrum.”

Large media conglomerates have enormous power through a variety of effective tools to influence, modify, and censor information disseminated through the major media outlets. Only the U.S. Government wields greater power in that respect.

Here is a specific example of how The Disney Company recently attempted (and thankfully failed) to deny the Los Angeles Times access to advance screenings which are critical to the paper’s ability to do its job.

Access to credible sources is the lifeblood for any journalist. A journalist with sources is called an unemployed journalist.

So why would Disney deny the LA Times access to their advance screenings?

Case Study: Disney Bans LA Times

This is a note the Los Angeles Times offered to its readers last November:

The annual Holiday Movie Sneaks section published by the Los Angeles Times typically includes features on movies from all major studios, reflecting the diversity of films Hollywood offers during the holidays, one of the busiest box-office periods of the year. This year, Walt Disney Co. studios declined to offer The Times advance screenings, citing what it called unfair coverage of its business ties with Anaheim. The Times will continue to review and cover Disney movies and programs when they are available to the public.

So why was the LA Times excluded from advance screenings of Disney films during the 2017 Christmas season?

LA Times writer Glenn Whipp explained on Twitter that The Disney Companywas unhappy with the LA Times’ investigation into Disney’s questionable business ties in Anaheim, California, home of the company’s Disneyland theme park.

Apparently, the LA Times’ critical reporting on how The Disney Company‘strong-armed’ Anaheim’s local government was not well-received at Disney headquarters, prompting the company to blacklist the LA Times from interviews and advance screenings of Disney films in late 2017.

However, days after Disney banned the LA Times, other critics condemned the Disney action and compelled the company to lift its screening ban of the LA Times. Nonetheless, Disney made its point clear to entertainment journalists: Don’t cross the Mouse.

Since their late-2017 kerfuffle, Disney and the LA Times are cooperating again, but the recent approval of the Disney/Fox merger should raise an alarm for journalists. With every new Disney acquisition, its control over the information and entertainment landscape grows. With their acquisition of Fox’s entertainment properties, Disney will add the Avatar, The X-Men and Planet of the Apes franchises to its portfolio. And for every entertainment journalist working today, the Disney/Fox merger just makes the likelihood of their pissing off Disney (and losing access to critical industry sources) a little more likely.

Where media control is concentrated, press freedom suffers

What evidence exists showing the negative effects of media consolidation on press freedom? The amount of published research demonstrating this connection is small, but growing (some recent examples can be found: here, here, and here).

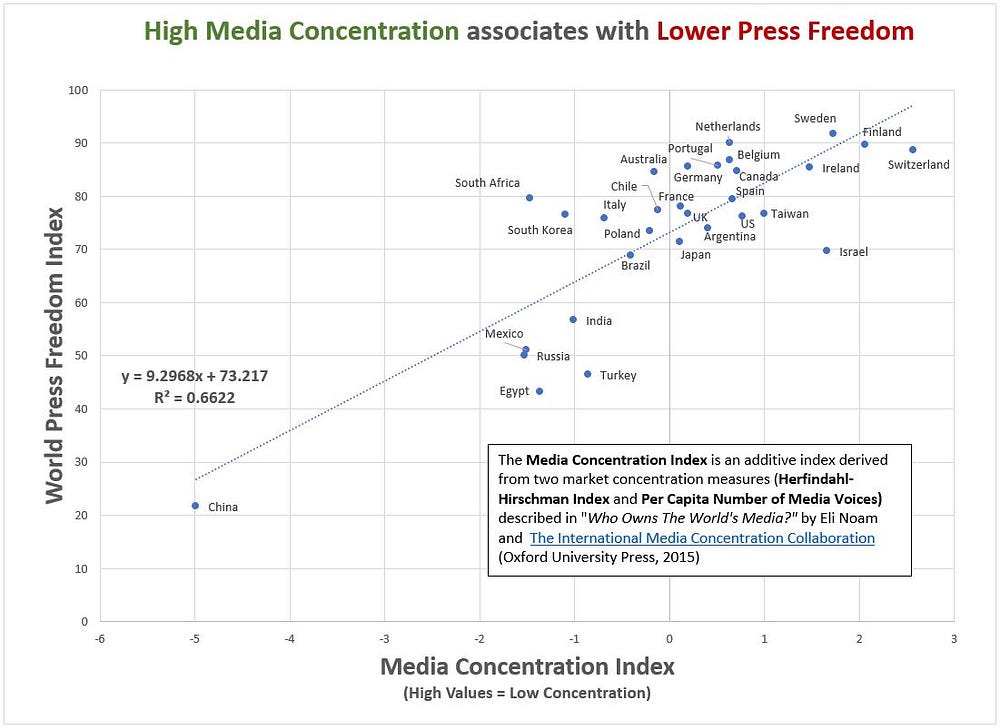

Along with RSF and Freedom House’s empirical work on press freedom, Columbia University Economics Professor Eli Noam has pioneered some expansive work on quantifying levels of media concentration across the globe.

In his 2016 book, Who Owns the World’s Media?, Noam and his collaborative team provide a data-driven analysis of global media ownership trends and their drivers. Using 2009 data (or later), they calculate overall national concentration trends, the market share of individual companies in the overall national media sector, and the size and trends of transnational companies in overall global media.

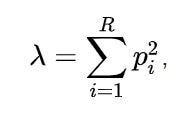

Employing a variety of concentration measures — in particular, the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) and the Per Capita Number of Voicesfor firms with at least 1% market share (PCNV), both commonly used measures of market concentration — Noam computes media concentration scores for 30 countries where sufficient market share data are available.

The HHI (λ) is generally computed as follows:

Within each country, Noam computes an HHI score for each media sector and creates a total HHI score using a weighted average across media sectors.

The HHI is influenced by the relative size distribution of the media firms in each country and is not related to a country’s absolute market size. Whereas, the Per Capita Number of Voices (PCNV) is heavily influenced by a country’s population size. Hence, the U.S., China, India, Russia, and Brazil have very low PCNV scores (high media concentration). Also, for the graph below, RCF’s World Press Freedom Index was inverted (100 — WPFI) for ease of interpretation (i.e., high values of the inverted WPFI equals high levels of press freedom).

The Results

Figure 5 reveals a negative linear association between press freedom and media concentration (as measured by an additive index combining the HHI and PCNV scores computed by Noam).

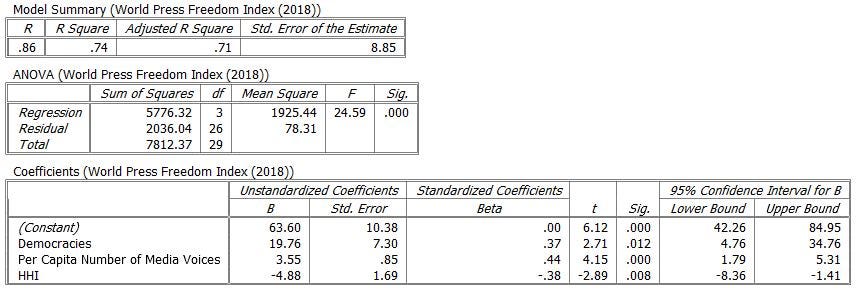

While China is clearly an extreme outlier, pulling the relationship into a strong positive direction, its exclusion from the analysis does not change the significance of the relationship. The linear regression models shown in the Appendix — using these explanatory variables: HHI, PCNV, Media Concentration Index (HHI+PCNV) and an indicator variable for democracies — found all four variables to be significantly associated with press freedom. Overall, both linear models explained almost three-quarters of the variance in press freedom.

Figure 5: Relationship between Press Freedom & Media Concentration

Notice in Figure 5 the location of Egypt, India, Russia, Turkey, Mexico, and China. All five countries have experienced significant violence against journalists in the past decade, according to RCF, and are either ruled by autocratic regimes (China, Russia, Egypt) or are democracies under significant internal stress (Mexico, Turkey, India). Press freedom and autocracies are incompatible.

Even within the subset of democratic countries, there remains a significant positive relationship between press freedom and media concentration. In countries such as Switzerland, Ireland, Finland, Sweden, Belgium, and the Netherlands, where media pluralism is strong, their press freedoms are among the highest in the world. Though, Israel is an interesting outlier (low media concentration / relatively low press freedom).

Europe addresses media pluralism as the U.S. continues to approve mega-media mergers

Much of the recent research on media pluralism and market concentration relates to Europe, with the most comprehensive research conducted by the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute. CMPF, a European Union co-funded research center, publishes the Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) to assess the risks to media pluralism in a given country.

In its 2016 MPM report, the CMPF concluded: “Amongst the 20 indicators of media pluralism, concentration of media ownership, especially horizontal, represents one of the highest risks for media pluralism and one of the greatest barriers to diversity of information and viewpoints represented in media content.”

The European Union is actively monitoring media concentration, even using Russian election meddling in the U.S. and Europe as one of the justifications for addressing the issue. In March 2017, the EU’s High Level Expert Group (HLEG) for online disinformation concluded that one way to counter disinformation is through safeguarding the diversity of the European news media. In May 2017, the European Parliament adopted HLEG’s recommendation to create an annual mechanism to monitor media concentration in all EU Member States.

And what has the U.S. done for the past two decades with respect to media concentration?

Despite a significant number of major media mergers since the 1996 Telecommunications Act, most recently the Disney-Fox merger which still needs antitrust approval from Europe before it can be executed, the U.S. has not been silent on media pluralism and the dangers of media consolidation.

In 1945, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in AP v. United States, “[the First] Amendment rests on the assumption that the widest possible dissemination of information from diverse and antagonistic sources is essential to the welfare of the public, that a free press is a condition of a free society.” In its 8–0 ruling (Justice Robert Jackson did not participate in the ruling), the Court upheld media ownership regulations to ensure source diversity, arguing “freedom to publish is guaranteed by the Constitution, but freedom to combine to keep others from publishing is not.”

Officially, the FCC’s policy objectives are competition, localism and diversity. Thus, before media mergers can occur they need approval from the FCC to ensure competition, localism and diversity are not threatened by a proposed merger.

In 2003, the FCC relaxed its ownership rules by eliminating cross-media ownership regulations in media markets with eight or more television stations, and allowed newspaper/television/radio cross-ownership in media markets served by four to eight television stations.

To assist the FCC in this new regulatory policy, the FCC developed a Diversity Index in 2002, which measured viewpoint diversity using a formula related to the Herfindahl-Hirschmann Index (HHI), a metric U.S. antitrust authorities have used to assess market competitiveness (i.e., concentration). The FCC Diversity Index (FDI) used consumers’ average time spent with each medium to weight its importance. It then assigned equal “market shares” to each outlet within each medium and combined those “market shares” for commonly owned outlets.

The FDI was controversial at its onset with many consumer advocacy groups arguing that it failed to capture the real degree of media concentration occurring in the U.S.

During testimony before the FCC in 2003, Dr. Mark Cooper, Director of Research for the Consumer Federation of America, offered this assessment of the FDI:

“The decision to allow newspaper-TV cross ownership in the overwhelming majority of local media markets in America is based on a new analytic tool, the Diversity Index, that was pulled from thin air at the last moment without affording any opportunity for public comment. The Diversity Index played the central role in establishing the markets where the FCC would allow TV-Newspaper mergers without any review. It produces results that are absurd on their face.”

“The Commission arrives at its erroneous decision to raise the national cap on network ownership to 45 percent and to triple the number of markets in which multiple stations can be owned by a single entity because it incorrectly rejected source diversity as a goal of Communications Act. The Commission ignored the mountain of evidence in the record that the ownership and control of programming in the television market is concentrated and extensive evidence of a lack of source diversity across broadcast and non-broadcast, as well as national and local markets. Allowing dominant firms in the local and national markets to acquire direct control of more outlets will enable them to strengthen their grip on the programming market, which undermines diversity and localism.”

Twenty-two years ago, President Bill Clinton signed the Telecommunications Act of 1996, a sweeping piece of legislation that was “essentially bought and paid for by corporate media lobbies…and radically opened the floodgates on mergers,” according to the media watchdog, Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR).

Understandably, PACs and lobbyists for the big media companies put their money behind Hillary Clinton in 2016 (about $50 million, not including internet-related PACs or individual contributions…and that does not include donations to the Clinton Foundation from media-related sources). But, as we’ve seen so far in the Trump administration, the media mergers have continued unabated and, if anything, Trump’s presence in the White House has lifted profits for all of the major media companies.

Why does this all matter?

The news media plays a critical role in informing the public about our democracy and, as we saw in the 2016 election, the mere possibility that malevolent forces might have manipulated information in that election is unsettling. Add in social media and other new media platforms and the potential for real mischief is substantial.

But it isn’t just foreign actors like Russia that we need to guard against. We need to look closely at the domestic forces that can censor and manipulate what information Americans receive.

“How can we have a real debate about media issues, when we depend on that very media to provide a platform for this debate?” asks Boston journalist Michael Corcoran. “It is no surprise, for instance, that the media largely ignored the impact of Citizens United after the Supreme Court decision helped media companies generate record profits due to a new mass of political ads.”

“Democracy suffers when almost all media in the nation is owned by massive conglomerates. In this reality, no issue the left cares about — the environment, criminal legal reform or health care — will get a fair shake in the national debate,” laments Corcoran.

Of course, it is not just the progressive left that suffers under the American media oligarchy — any viewpoint or perspective substantially deviant from the interests of the media oligarchs suffers. The agenda-driven journalism that defines most of what we watch and read today, effectively discharged from the strict requirements of objectivity and backed by the enormous resources of the major media companies, is becoming ever harder to counteract.

Conversely, the major media companies — along with the social media giants — are increasingly equipped to suffocate news and information that threatens their corporate interests.

If Comcast, News Corp., Viacom, Disney, CBS, and Time Warner collectively or informally decide a U.S.-backed invasion of Iran will help keep their corporate revenues growing, what independent news outlet or journalist is going to have the coverage and market share to challenge them?

Democracy Now, The Intercept, and The Empire Files are not enough to defend against the palpable threat the major media companies pose to American journalism and, by necessary extension, the American democracy.

- K.R.K.

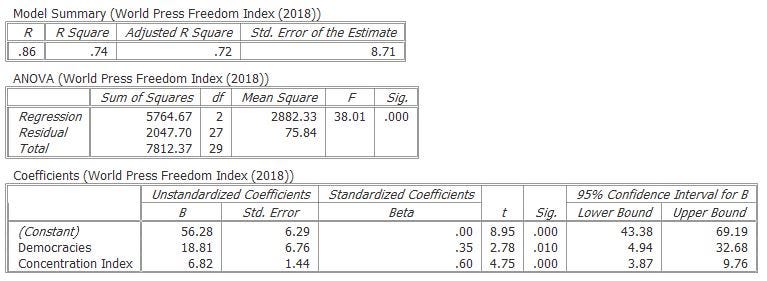

APPENDIX: LINEAR REGRESSION MODELS

Three-Variable Model

Dependent Variable: Press Freedom as measured by WPFI

Independent Variables: HHI, PCNV, Democracy Indicator

Two-Variable Model

Dependent Variable: Press Freedom as measured by WPFI

Independent Variables: Concentration Index (HHI+PCNV), Democracy Indicator