By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; January 31, 2019)

In early January, New York Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez chided CBS News for failing to have even one African-American journalist among its newly selected 2020 election team.

“This (White House) admin has made having a functional understanding of race in America one of the most important core competencies for a political journalist to have, yet, @CBSNews hasn’t assigned a ‘single’ black journalist to cover the 2020 election,” tweeted Ocasio-Cortez soon after CBS released its new election reporting team.

“CBS, your 2020 election team is disgraceful,” was the headline at one Virginia newspaper.

“CBS News’ decision to not include Black reporters on their 2020 Election news team further proves the voting power and voices of Black America continue to be undervalued,” said the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in a press release.

Whether CBS News’ human resource decisions are within Ocasio-Cortez’ lane of responsibility is questionable, but not the concern in this essay. Nor are we concerned with whether CBS News should feel defensive about their hiring decisions. That is a political debate.

The topic for this essay is how CBS News could have easily avoided this controversy.

Best talent and diversity are complementary but independent hiring goals

American business schools are filled with theories, graduate seminars and practicums on the best hiring practices for businesses and organizations to attract the best talent and achieve diversity. Those are complementary goals, but achieving one is no guarantee in achieving the other.

But as revealed in the CBS News case, many organizations still don’t meet both goals in tandem. Surprisingly, the solution is well-known and quite easy — yet, for many reasons, organizations resist this solution.

The solution is to introduce random-selection at critical points in the hiring process as a way to ameliorate the common biases introduced by human judgment.

Humans are inherently and hopelessly biased when it comes to making hiring decisions.

In the age of identity politics and demands to rectify historical injustices based on ascribed characteristics such as race, ethnicity or sex, a variant of random selection — stratified random-selection — offers the most defensible and equitable method for addressing the twin hiring goals.

Stratified random-selection (or sampling) divides a population into smaller, homogeneous groups (called strata) where the members of each group share similar characteristics. A predetermined number of members are then randomly selected from each stratum.

This idea is not new and has been suggested, for example, as one way to make the acceptance process at universities and colleges more representative and fair.

The Atlantic’s Alia Wong wrote an excellent article last year on the proposals to adopt the random-selection process to fix the admissions problems at elite U.S. universities. Though she concluded it is unlikely any Ivy League school is soon going to adopt such a process, her reporting did identify schools in Europe where random-selection has been used with some success (e.g., England’s Leeds Metropolitan University and Huddersfield University; and many universities in the Netherlands).

The Washington Post also recently published an opinion piece supporting the idea of a random-based selection process for the college admissions.

Some HR academics and theorists are suggesting Artificial Intelligence (AI) could be used to eliminate human biases in the hiring process, but recent research has shown AI algorithms also bring race and gender biases into the equation. AI algorithms, after all, are written by humans whose biases end up encoded into the algorithms.

UK computer scientist Joanna Bryson (University of Bath), co-author of the AI hiring algorithm research, warns that AI’s problems in making hiring decisions is a double-whammy: Not only can AI be prejudiced (because of human programmers), but unlike humans, AI is not equipped to consciously counteract learned biases. Or, at least, it is still difficult to program such types of morality into AI algorithms.

Until the time that becomes possible, the easier solution is to incorporate a smidgen of randomness into the process.

A hypothetical example of a random-enhanced hiring process

In the context of a hiring situation, such as the one faced by CBS News, the randomized selection process might go as follows:

(1) A news organization needs to hire 12 people for an anticipated event. The organization wants the new hires to reflect the racial-ethnic diversity of the country (i.e., hiring target percentages). [For the sake simplicity in describing the random-selection process, let us assume an equal number of men and women applicants are processed within each strata.]

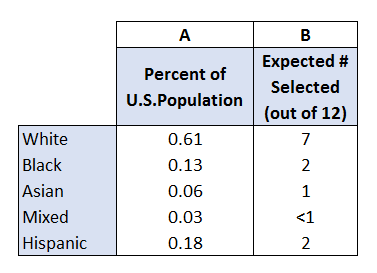

According to the U.S. Census (column A in the table below), the following represents the racial-ethnic percentages of the U.S. population: Whites (61%), Blacks, (13%), Hispanic (non-white) (18%), Asian (6%), Mixed-race or Other (3%). From the table, we see how the 12 new hires should breakout for each racial-ethnic strata (column B). Since Mixed-race is such a small category, the organization may combine the strata with the next smallest group (Asian):

(2) The organization recruits, receives and processes 100 ‘credible’ applicants where the applicants meet some predetermined minimum requirements for the new positions. Note: This step has the potential to introduce significant bias into the hiring process, as the applicant pool may not reflect general population characteristics.

(3) Those applicants are separated into homogeneous groups (strata) and a determination is made whether each applicant qualifies for a follow-up interview(s). At this step, that selection could be determined through random selection — depending on the thoroughness of the screening process in Step 2 — or human judgement.

(4) From the follow-up interview(s), a final set of substantively and highly qualified candidates are identified. If one strata does not have any (or enough) applicants determined to be substantively qualified, the organization would need to go back and re-recruit for that strata and repeat Steps 1 through 3.

(5) The final hiring selection would be determined through random-selection — not human judgement. The number selected from each strata would be determined by the target percentages in Step 1 (column B in the table).

The stratified element in this hypothetical hiring process is not absolutely necessary. The stratification merely removes the random component from the race-ethnicity breakout of the final hires. If an organization is confident that its applicant pool is drawn from a broad range of society, it would be defensible to utilize simple random sampling and forgo the stratification of applicants into the race-ethnicity strata.

There will be resistance to random-selection

A commonly heard complaint about using random-selection in the college admissions process is that it goes against the America’s historical ethic of individualism and merit-based advancement. If advancement is random, it must therefore throw individual merit out the window, right?

Forbes’ Willard Dix writes:

“Calling the process a “crapshoot” works as a metaphor for the applicant and it’s handy for general conversation, but it’s not truly as random as it seems from the outside. Yes, at some point in the process candidates can look very similar and choosing among them can be a matter of time of day, mood of the admission officer or the overabundance of oboe players. But human foibles and flaws as well as accomplishments and distinguishing features are integral parts of the process and an expression of our belief in being the master of one’s own fate, no matter how misguided that may be.”

Dix’ criticism is well-received but misunderstands the random-selection concept. It is not a “crapshoot” or even random. While the final selection step possesses a random-selection component, every step up to that point reflects the same merit-based ideals Dix assigns to the current college admissions system.

Random-selection hiring processes (or college admissions) will not result in unqualified people filling work positions or college admissions lots.

It will result in the people filling these positions as being more representative of the population from which they are drawn.

The above hiring process is not complicated nor dramatically different from what already occurs in most organizations. The novel addition to the process is Step 5.

If the final set of applicants (Step 4) are highly qualified — and, yes, decisions in Steps 1 through 4 will still include human bias — using random-selection at the last step offers an organization a final line of defense against bad hiring outcomes like that one at CBS News.

Instead of allowing human judgement to bias the entire hiring process, random chance is the final, unbiased judge.

Had CBS News used the random-selection process suggested here, they wouldn’t have faced the criticisms they did from Ocasio-Cortez, et al.

- K.R.K.

Comments and critiques can be sent to: kroeger98@yahoo.com