By Kent Kroeger (June 26, 2018)

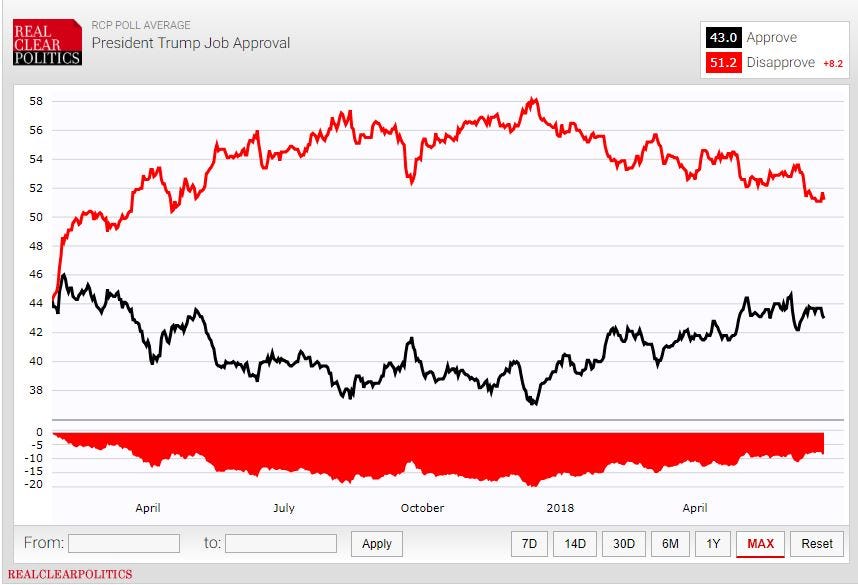

On June 11, 2018, President Donald Trump’s average job approval rating, according to RealClearPolitics.com, stood at 42.9 percent.

On June 12, 2018, President Trump shook hands with North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un to start a negotiation process that could lead to the end of the Korean War and the de-nuclearization of the Korean peninsula.

By June 16th, Trump’s average approval rating had risen to 43.8 percent — a mere 0.9 percentage point increase.

Trump’s critics justifiably argued the Singapore Summit was inconsequential in that it produced nothing concrete other than an agreement to continue the negotiation process. Nonetheless, the images of the two leaders meeting were powerful and genuine optimism now exists about ending North Korea’s nuclear weapons program.

Zero. Point. Nine.

Fine, so maybe the public isn’t easily manipulated by staged presidential media events anymore. Surely, the public can’t ignore the humanitarian travesty that was the Trump administration’s ‘zero tolerance’ immigration policy which included the premeditated separation of families upon their apprehension by U.S. border patrol agents. Can they?

As the news about the family separations began to dominate the news cycle immediately after the Singapore Summit, Trump’s job approval ratings stood at 43.8 percent. After two weeks of intense and predominately negative news coverage regarding Trump’s family separations policy, his job average job approval rating is at 42.9 percent — a measly 0.9 percentage point drop.

What does it take to move the needle on a president’s job approval numbers these days?

A lot, apparently.

In the age of hyperpartisanship, does the news matter anymore?

Most people don’t experience a president’s job performance first-hand. While we do directly experience the state of the economy; and, if we are in the military or have family and friends serving, may have some direct experience with wartime. But, for the most part, what the average person knows about the president’s job performance comes to them, directly or indirectly, through a news media filter.

Democratic theory posits that democracies are strengthened by an independent news media motivated to ensure greater transparency and accountability on the part of political leaders and institutions.

And the empirical evidence as generally confirmed this relationship between public opinion and the news media.

In their 1992 landmark study on what moves public opinion, Benjamin Page, Robert Y. Shapiro, and Glenn Dempsey found that “news variables alone account for nearly half the variance in opinion change” among American adults.

Page, Shapiro and Dempsey wrote: “Much of the impact of objective events is indirect, mediated by U.S. political leaders and commentator and experts in ways that we have not yet fully untangled. Events-like statements and actions from foreign countries-seldom speak directly and unambiguously to the public; rather they affect public opinion mostly through the interpretations and reactions of U.S. elites.”

But Page, Shapiro and Dempsey’s research occurred back when the news media was still viewed by the public as mostly non-partisan and objective. There was no Fox News Channel or MSNBC. Though, many conservatives even then decried the ‘liberal bias’ in the mainstream news media. Nonetheless, the prevailing professional ethic among journalists in the early 1990s was still to remain non-partisan and objective in their reporting.

Yet, what happens if the news media, particularly those news outlets dominated by corporate interests (i.e., profit motive), adopt a partisan or biased perspective in the pursuit of readers and viewers? What if, in fact, the dominate news outlets are all either openly partisan or perceived by the public to be such?

If most people were themselves non-partisan and objective, they might endeavor to get their news from a variety of sources in order to come to an enlightened opinion on the news and events of the day.

Unfortunately, most Americans are not objective and, in fact, are becoming increasingly partisan.

We are becoming so partisan that the term hyperpartisan is often used to describe Americans today. Through our living arrangements, workplaces, and online social groups, we are constructing walls around ourselves to keep out those with opinions divergent from our own.

It is somewhat ironic that, at a time when many of us celebrate identity group diversity, we also consciously and proactively seek to reduce our exposure to opinion diversity.

One possible consequence of this trend may be that, as individuals, we increasingly fail to educate ourselves with respect to the diversity of ideas and opinions existing outside our own personal realm. And we are enabled in keeping dissonant ideas and opinions out of our personal space through our news outlet preferences.

If you believe the Fox News Channel’s viewers are dumb and racist hicks, why would you pollute your life with their preferred news source? You wouldn’t. And vice versa. If you believe MSNBC’s viewers are elitist snobs who prefer France over America, why would you watch Rachel Maddow or Chris Hayes?

What could go wrong with this tacit arrangement?

…I don’t know…perhaps the viability of our democracy? Perhaps our democracy’s ability to objectively incorporate new and pertinent information into the political realm, thereby making it difficult for our political institutions to make informed and rational decisions?

How might this dysfunctional result of hyperpartisan become apparent?

I believe an increasingly partisan public, in isolating their news sources to only those with similar partisan biases, makes it more difficult for new (unanticipated) facts and events to shape our political discourse in such a way to maximize the quality of policy decisions and outcomes.

For example, if someone filtered their information about the Singapore Summit through ‘liberal’ news outlets (MSNBC, CNN, Washington Post, New York Times, NPR), they probably formed a negative opinion about its historical importance or likelihood of its achieving the de-nuclearization of North Korea. If their news source was the Fox News Channel, they most likely would have formed a positive opinion about the Summit.

If you are not exposed to contradictory information about Donald Trump, why would you ever change your opinion about him? The result would be fairly stable presidential job approval numbers that may only change as slower-changing contextual factors change (e.g., the economy).

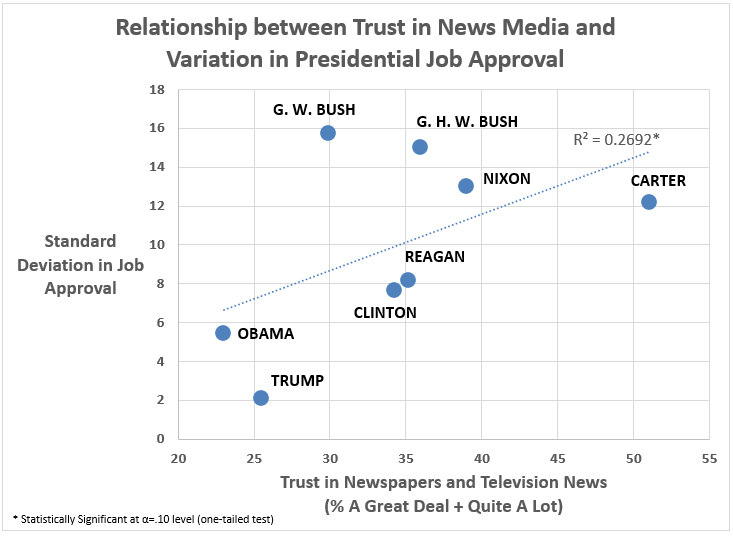

In other words, we would notice a distinct reduction in opinion variation across time…which is exactly what we see in the presidential job approval data (see graph below):

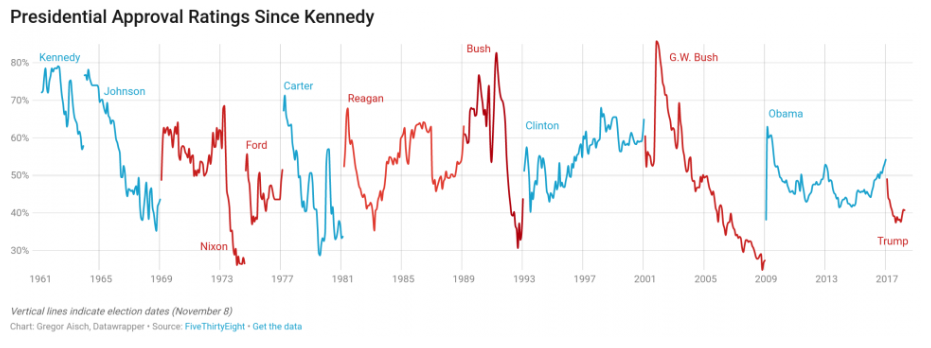

There are two striking features with respect to presidential job approval over time. First, within every administration, job approval tends to decline consistently across a president’s term. That is why the first 100 days is so important in the policy-making process.

The other striking feature is how the job approval numbers for the last two presidents (Obama and Trump) tend to operate within a relatively narrow range of values. With the exception of his first few weeks in office, Trump’s approval has varied between 37 and 43 percent approval. Likewise, Obama’s approval drifted mostly between 45 and 55 percent throughout his two terms.

In contrast, Jimmy Carter’s job approval ranged between 30 and 70 percent, while Ronald Reagan’s ranged between 35 and 65 percent, primarily. The table below summarizes the variance differences in job approval across presidential administrations.

And why are we seeing less variation in job approval for our recent presidents? I contend that the number one suspect is the increased separation and isolation of American society by partisan lines. There are other possible explanations: (1) Today’s economy may be less prone to dramatic changes than in the past, (2) Presidents today may be better at minimizing dramatic declines in job approval (i.e., better at manipulating bad news), or (3) the meaning of presidential ‘job approval’ may have changed in Americans’ minds over time. And there are certainly other possible explanations.

But the most likely cause, in my mind, is the possibility that the average American increasingly avoids exposure to dissonant information and opinions by only receiving their information from partisan news sources. If true, we should also expect to see more and more Americans lose their trust in the news media in general as they start perceiving ‘other’ news outlets as being partisan and biased.

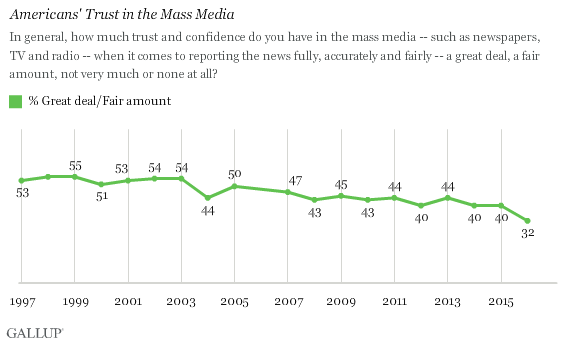

And that is precisely what we are seeing in the aggregate opinion data (see graph below):

“Over the history of the entire trend, Americans’ trust and confidence hit its highest point in 1976, at 72 percent, in the wake of widely lauded examples of investigative journalism regarding Vietnam and the Watergate scandal,” notes Gallup Poll analyst Art Swift. “After staying in the low to mid-50s through the late 1990s and into the early years of the new century, Americans’ trust in the media has fallen slowly and steadily. It has consistently been below a majority level since 2007.” Not coincidentally, the two presidents since 2007, Obama and Trump, have experienced the lowest levels of variance in their job approval ratings.

Our final graph (below) shows the relationship between the variance in a president’s job approval ratings and the trust in the media held by the American public during each president’s tenure. The relationship is statistically significant.

When Americans distrust the news media, in general, their opinions regarding the job performance of the president tend to become more stable. As it is less likely they are exposed to information contradicting their own partisan bias, they are also less likely to change their opinions regarding political matters such as the president’s job performance.

If true, that is a real problem for our democracy. If all people hear is information confirming what they already believe, how can they properly react to objective and important changes in the information ecosystem?

The above graph is not conclusive evidence but is suggestive of a serious dysfunction without our democracy. A malady that, if left uncorrected, may make it increasingly difficult for our elected leaders to implement timely and constructive decisions when addressing serious social problems.

-K.R.K.