By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; January 9, 2019)

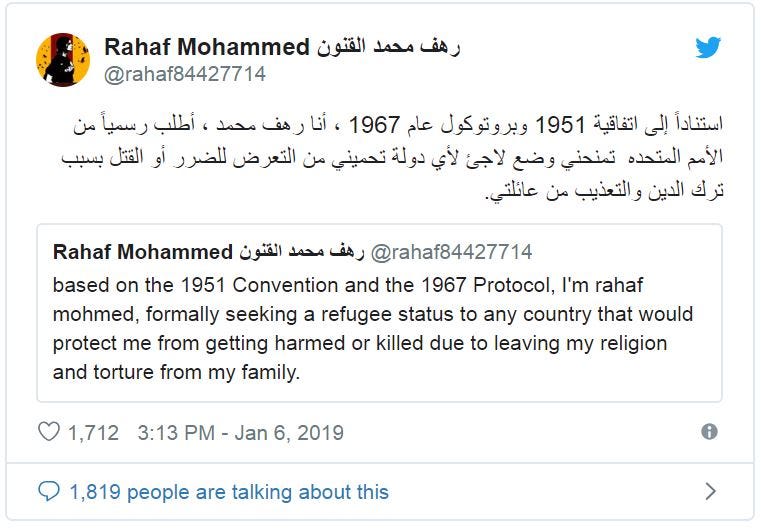

No story has made my heart sink faster than the recent one about Rahaf Mohammed Alqunun — a Saudi Arabia teen allegedly fleeing to Thailand from her family (living in Kuwait) out of fear they would kill her.

At this point in the story, events are fluid and many facts are still unknown. The evidence we do possess is mostly a series of conversations between Rahaf and her Twitter followers, along with officials statements coming from the Thai government and the United Nations Refugee Agency stating, at least for now, support for her staying in Thailand until her case can be resolved.

In less than 48 hours of her first asylum plea via Twitter, Rahaf’s Twitter account has attracted tens of thousands of new followers. Whether Rahaf’s story ends happily is still to be determined.

Similar stories of Saudi women but did not end well have emerged in the past few years. Here are two of them:

Where is Dina Ali Lasloom?

Dina Ali Lasloom is a Saudi woman who sought asylum in Australia but was detained at the Ninoy Aquino International Airport in Manila, Philippines on April 10, 2017, and deported back to Saudi Arabia, accompanied by two of her uncles, on April 11, 2017.

Below is the last known picture of Dina (see talking to her two uncles at the Manila airport).

Her reason for trying to leave Saudi Arabia? In a self-recorded video, Dina says that she is seeking asylum and will be killed if forced to return to her family. In another video, taken by a Canadian tourist in the Manila airport while Dina was being detained by Philippine authorities, captures Dina screaming at a Saudi woman, who had accompanied Dina’s uncles.

According to eyewitnesses on Dina’s return flight to Saudi Arabia, she was covered by a blanket, her mouth taped shut, and physically resisting as her uncles forced her onto the plane.

Since returning to Saudi Arabia on April 11, Dina has never been seen again. A anonymous Saudi government official told Bloomberg that, upon arrival in Riyadh, Dina Ali was taken to a detention facility for women aged under 30 but did not face any charges. However, feminist activist Moudhi Aljohani, who says she talked to Dina on the phone while she was detained in the Manila airport, is less sanguine. “It is most likely that she is not alive,” she says.

The “Double Suicide” of Two Saudi Sisters in New York’s Hudson River

This next story is perhaps more chilling. On October 24, 2018, the bodies of sisters Tala and Rotana Farea, Saudi citizens living in Virginia with their family, were found along the banks of New York’s Hudson River bound together by duct tape in a way suggesting it was meant to hold them together but not bind them. According to New York City Police, there was no evidence of foul play as they concluded the deaths were part of a suicide pact.

Assuming the conclusions of the NYC Police are correct, it still begs the question, why would two sisters do such a thing?

Sources told investigators that the sisters once said they would “rather kill themselves than return to Saudi Arabia.” Their mother reportedly told local reporters that the Saudi embassy in Washington told the family they would need to return to Saudi Arabia.

As the sisters’ full story remains a puzzle, the basic outline sounds familiar to human rights observers that track the fate of Saudi women attempting to find asylum outside the Kingdom.

“Although there are no official statistics, anecdotal evidence from cases reported in Saudi media and from human rights advocates suggest dozens of Saudi women — some with their children — have attempted to flee abroad in recent years,” says journalist Aya Batrawy who has covered a number of these stories in her career.

Whether the stories of Rahaf, Dina and the Farea sisters represent a trend is difficult to say. If they do, these asylum cases are happening at a time when Saudi women have seen recent gains in freedom, including the right to drive, and the right to run and vote in local elections. That those gains occurred because of growing discontent among Saudi women is entirely possible as well.

The Data Paints a Bleak Picture for Saudi Women (and Muslim Women, in general)

As the anecdotal evidence of systematic abuse continues to emerge from Saudi women seeking asylum in the West, the quantitative evidence substantiates their stories.

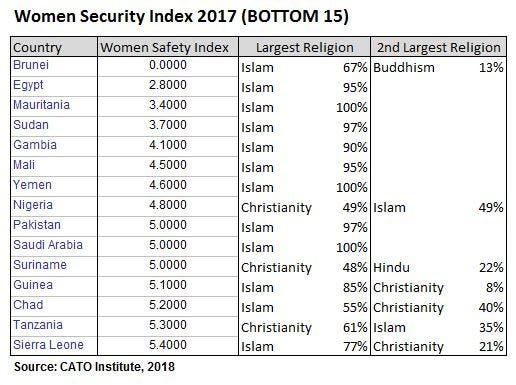

As part of its annual computation of the Human Freedom Index (HFI’s), the CATO presents the “state of human freedom in the world based on a broad measure that encompasses personal, civil, and economic freedom.” Among the HFI’s many sub components is a Women Security Index (WSI) which is computed for over 170 countries and is based on: (1) the prevalence of female genital mutilation, (2) the gender bias in mortality, and (3) the inheritance rights of wives and daughters. The WSI ranges between 0 and 10 where ‘0’ indicates low security for women and ‘10’ indicates high levels of security.

Figure 1 shows the Bottom 15 countries on the WFI — the lowest index score going to Brunei (WFI = 0.0), followed by Egypt (WFI = 2.8), Mauritania (WFI = 3.4) and Sudan (WFI = 3.7). Saudi Arabia has the 12th lowest WFI at 5.0 (tied with Suriname and Pakistan).

The relationship of the WFI to a country’s dominant religious culture is strong. Fourteen out of 15 countries at the bottom of the WFI are predominately Islamic or have a large Islamic minority.

Figure 1: Women (In)Security Index 2017 (Source: CATO Institute, 2018)

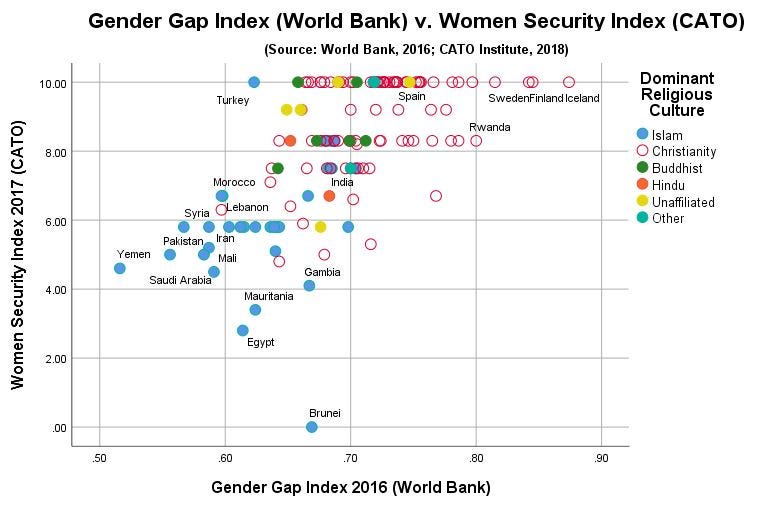

Another quantitative measure related to women’s equality and compiled annually is the World Bank’s Global Gender Gap Index (GGI).

The Global Gender Gap Index is the combination of four components: (1) Economic Participation and Opportunity, (2) Educational Attainment, (3) Health and Survival and (4) Political Empowerment. The highest possible country score is 1 (equality) and the lowest possible country score is 0 (inequality).

As seen in Figure 2, the GGI and WSI are positively correlated (Pearson r= .62) and reveal Islamic countries (the blue dots) again cluster on the low end for both indexes.

Figure 2: The World Bank’s Gender Gap Index (GGI) and CATO’s Women Security Index (WSI) — The Relationship to Religious Culture

The World Bank has been computing the GGI since 2006. Between 2006 and 2016, only one country, Sri Lanka, experienced a significant decline in their GGI (-0.05). Figure 3 shows the Top 10 countries experiencing the most significant increases in gender equality: Nicaragua (0.12), Nepal (0.11), Bolivia (0.11), Slovenia (0.11), and France (0.10).

Figure 3: Changes in Gender Gap Index (2000 to 2016) (Source: World Bank, 2016)

Among Islamic countries, Bangladesh (0.07), Chad (0.06), Saudi Arabia (0.6), Yemen (0.6) and UAE (0.5) saw the most significant increases in gender equality between 2006 and 2016.

If the World Bank’s GGI is any indication, there have been substantive improvements to women’s lives in Saudi Arabia since 2006.

Political scientist James Davies once postulated in the 1960s that “revolutions are most likely to occur when a prolonged period of objective economic and social development is followed by a short period of sharp reversal.” Since called the “J-curve” theory, Norwegian political scientist Carl Henrik Knutsen has offered tentative quantitative evidence supporting one aspect of the J-curve theory: “Short-term economic growth rates systematically affect the probabilities of attempted and of successful revolutions. Regimes in countries that experience economic crises are at increased risk of facing revolutionary threats and of eventually being thrown out of office because of them.”

Whether this finding relates to the propensity of Saudi women to carry out their own smaller, personal revolutions is highly speculative.

What we do know, anecdotally, is that (young) Saudi women are routinely putting their lives at risk in seeking asylum outside the Kingdom. The most recent example (Rahaf) may have a relatively happy ending. Many most likely have not.

It is also impossible to disentangle the human rights issue from the diplomatic necessities of the U.S. and Western democracies. Saudi Arabia is too critical to world economic growth to expect political leaders to lead on the issue of women’s rights in Saudi Arabia.

A long list of American notables — Barack Obama, Bill and Hillary Clinton, an assortment of Bushes, Michael Bloomberg, John Kerry, Condoleezza Rice, Bill Gates, Rupert Murdoch, Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, Tim Cook, and Bob Iger— lined up to meet the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman during his charm offensive in March 2018.

That fact is Saudi Arabia remains one the closest U.S. allies in the Middle East and will be for as long as the country needs their cheap oil (which might not be for as long as you think). Said President Donald Trump recently, “Saudi Arabia has been a great ally to me.” Sadly, the Saudi royals are not as great to their own people, especially Saudi women.

- K.R.K.