By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; February 20, 2019)

Donald Trump, the candidate, has a market share problem. His support has very little upside and — as of now — has a maximum potential market (vote) share of just 45 percent among eligible voters.

That will not win the next election. He needs a new strategy and he needs one fast.

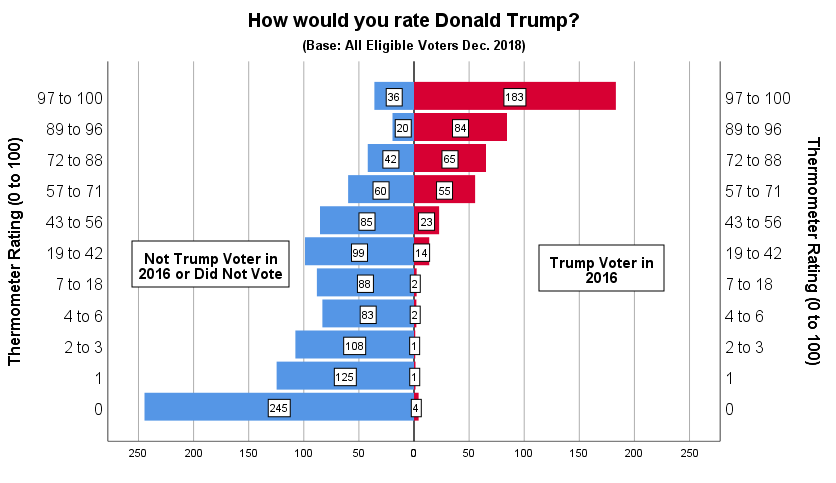

To demonstrate the problem, Figure 1 offers a simple volumetric analysis of eligible U.S. voters using data from the December 2018 American National Election Study (ANES).

Figure 1: How Eligible Voters Rate Donald Trump (Dec. 2018)

Data Source: 2018 American National Election Study (Pilot); Analytics by Kent R. Kroeger

First, assume voters that currently rate Trump 57 or higher on a 0–100 thermometer scale potentially will vote for him if the election were held today. Likewise, I estimate 60 percent of those rating him between 43 to 56 are potential votes for him today (the 60 percent estimate is based on percentages derived from the 2016 election). Finally, since we are seeking a maximum in vote share potential, assume any voter that voted for Trump in 2016 potentially will vote for him again (even if their rating of him is below 43).

This adds up to 45 percent of all eligible voters. Of course, many people won’t vote at all, but if non-voting is randomly distributed across levels of Trump support, the highest vote share Trump can expect (under the current status quo) is only 45 percent.

This is a gut-punching number if you work for the Trump White House or Republican National Committee (RNC).

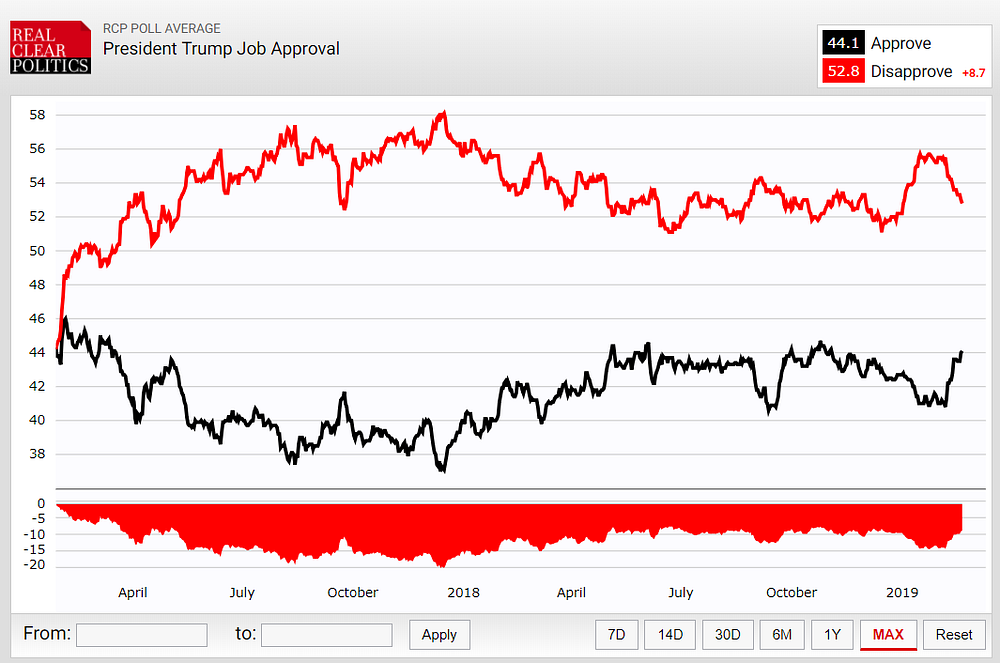

That potential vote share is noticeably similar to Trump’s maximum job approval rating over the first two years of his presidency — 46 percent (occurring at the start of his term in Figure 2).

Figure 2: Average Trump Approval Rating (RealClearPolitics.com)

Source: RealClearPolitics

This is not a coincidence. Trump has a hard ceiling when it comes to support and unless something shocks the system (e.g., a nuclear disarmament deal with DPRK or some national security emergency of the real kind), it is hard to see where Trump can go prospecting for new supporters.

White Republicans stand almost alone in the American electorate

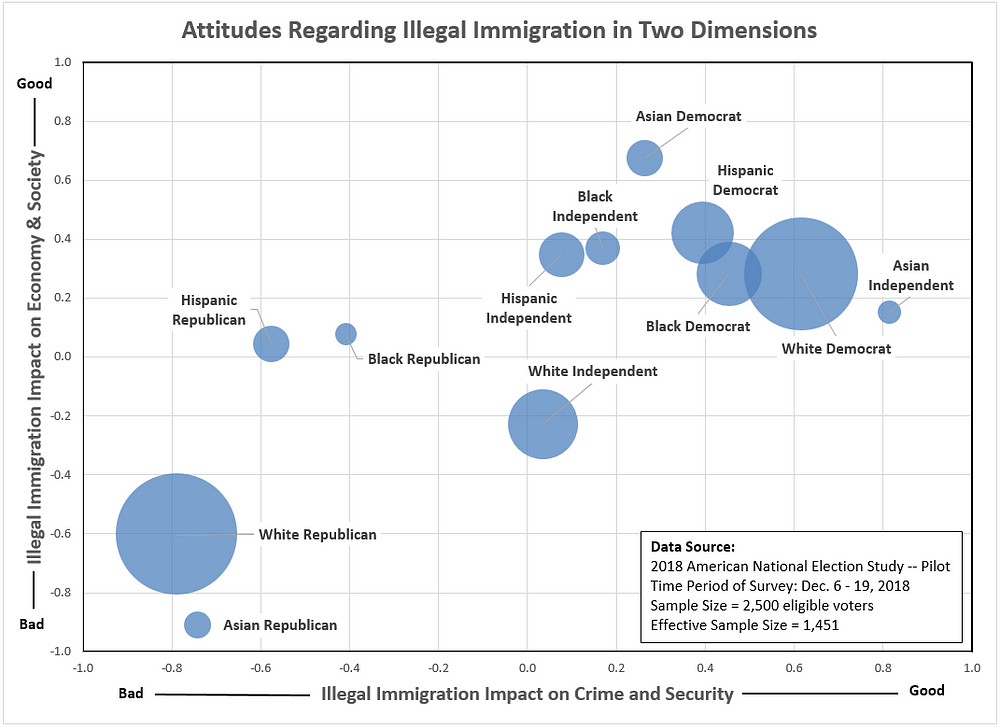

The independent voters (and ‘weak’ partisans) Trump needs to win reelection are too far removed in their attitudes from the GOP’s core voters to become probable Trump voters in 2020. The distance between independents and the Republican Party can be seen in two charts from the 2018 ANES.

The first chart (Figure 3) plots eligible voters by their partisan and racial/ethnic identification. The bubble size indicates the relative size of that voter segment — the biggest being white Republicans (31%), followed by white Democrats (27%), white independents (10%), Black Democrats (9%), Hispanic Democrats (8%), Hispanic independents (4%), Asian Democrats (3%), Hispanic Republicans (3%), Black independents (2%), Asian Republicans (2%), Asian independents (1%), and Black Republicans (1%).

In Figure 3, the horizontal axis is defined by an index score formed by illegal immigration questions from the 2018 ANES focused on crime and security. The vertical axis is defined by an index score formed by illegal immigration questions from the 2018 ANES focused on the economy and society (all data and SPSS coding syntax available upon request to: kroeger98@yahoo.com).

The relative distance between white Republicans and the other voter segments (except Asian Republicans) is substantively significant. White Republicans are much more likely to view illegal immigration has harmful to both the national economy and crime. In contrast, Hispanic Republicans view illegal immigration has impactful on crime and security, but no so much on the economy. This finding is consistent with other research on the immigration attitudes of Hispanic Republicans (here, here and here).

Figure 3: Voter Segments by Attitudes Regarding Illegal Immigration

Data Source: 2018 American National Election Study (Pilot); Analytics by Kent R. Kroeger

Problematic for Republicans in Figure 3 is the gap between white Republicans and white independents, who generally fall in the middle on both immigration indexes. While white independents have a slightly negative view of illegal immigration’s impact on the economy, their attitudes are not as extreme as white and Asian Republicans. However, white independents are almost equidistant between white Democrats and white Republicans, suggesting that the Republicans could still bring them into the voting fold with improved messaging and less extremism on the issue. In contrast, Hispanic, Asian and Black independents appear lost causes for supporting the Republicans on illegal immigration.

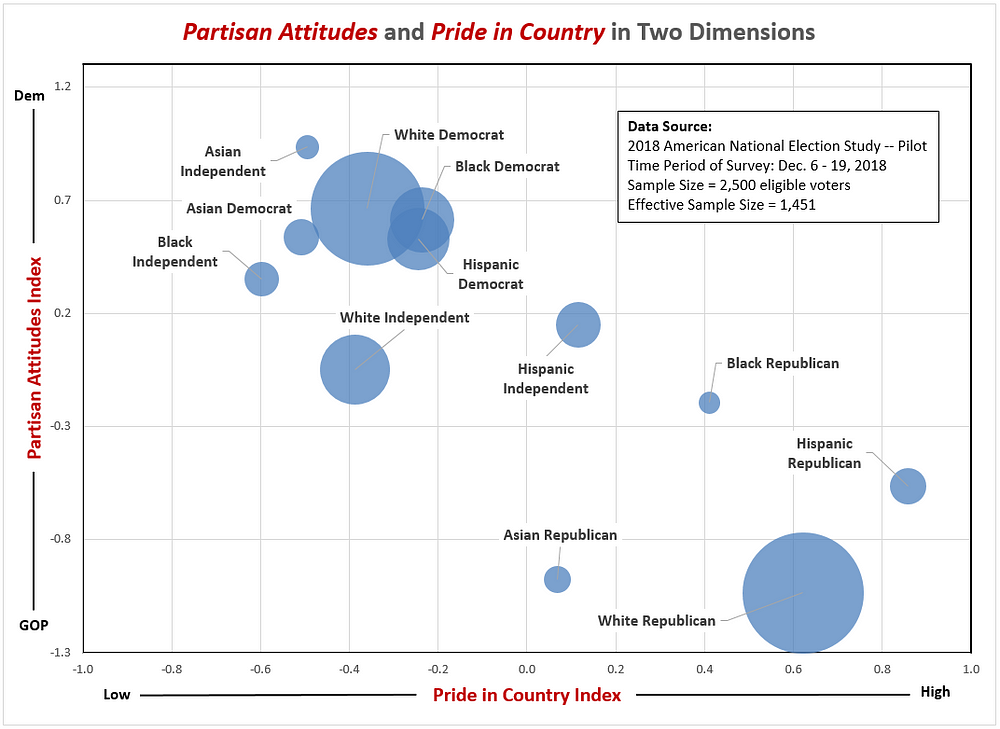

A similar analysis in Figure 4 focuses on partisan policy attitudes and national pride. And, again, white Republicans stand virtually alone relative to the bulk of the American electorate.

In Figure 4, the horizontal axis is defined by an index score formed by questions on the 2018 ANES related to national pride. The vertical axis is defined by an index score formed by a series of policy-related questions from the 2018 ANES shown to be highly correlated with respondents’ partisanship strength.

Figure 4: Voter Segments by Attitudes Regarding Partisan Issues and Pride in Country

Data Source: 2018 American National Election Study (Pilot); Analytics by Kent R. Kroeger

White Republicans are strikingly more patriotic and conservative in their policy views than the other voter segments. Only Hispanic Republicans are more patriotic and, on policy issues, only Asian Republicans are similarly conservative.

While legitimate methodological and theoretical criticisms can be made regarding the use of spatial distances to explain voting behavior, in the 2018 ANES data at least, the association (no claim of causation) between voter spatial distances and aggregate voting behavior was significant.

It feels safe to conclude that white Republicans have become so isolated from the American mainstream, without an immediate strategy adjustment by the GOP, it is difficult to see how Trump can achieve anything near the 46 percent of the popular vote he garnered in 2016. Without a major third party candidate cutting disproportionately into the Democrat’s voter base, the only question about 2020 is what will be the depth of Trump’s defeat and how will it impact down-ballot Republicans.

Trump cannot expect the same perfect storm that worked for him in 2016

If 2016 taught anything, never say never in American presidential elections. Still, the factors that played major roles in Trump’s 2016 upset victory over Hillary Clinton will not be in Trump’s favor the next time around.

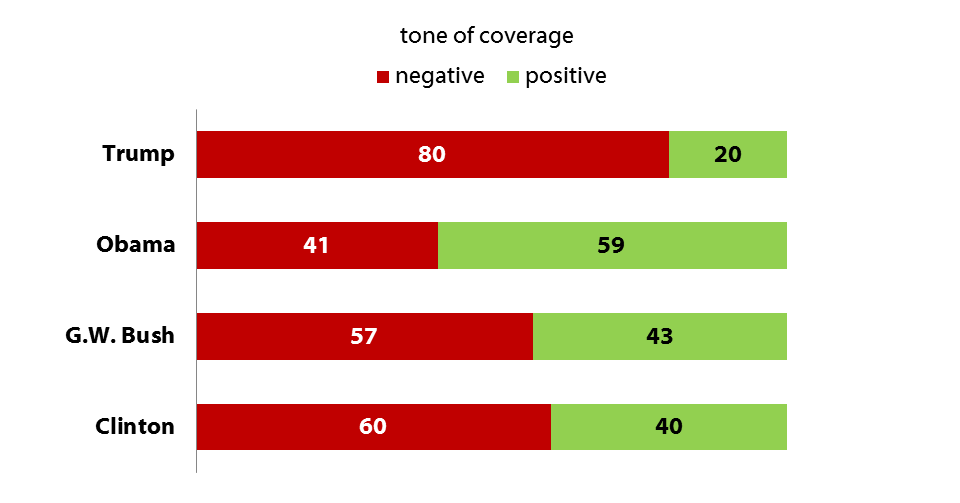

First, the overwhelming advantage in ‘free, unfiltered media’ gifted to Trump by the cable news networks in 2016 will not repeat itself in 2020. To the contrary, according to Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, the first 100 days of the Trump presidency experienced the most negative presidential media coverage of any president they’ve measured (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Tone of President’s News Cover in First 100 Days

Sources: Stephen J. Farnsworth and S. Robert Lichter, The Mediated President (2006), p. 37 for Clinton and Bush; Center for Media & Public Affairs for Obama; Media Tenor for Trump. Percentages exclude news reports that were neutral in tone, which accounted for about a third of the reports.

No evidence exists to suggest the tone of Trump’s news coverage has improved since the first 100 days. In fact, if we accept recent research from the partisan media watchdog, Media Research Center, over 90 percent of Trump’s news coverage has been negative in the first two years of his presidency.

Second, in 2016, Trump’s opponent made a whole host of significant strategic mistakes, along with coming into the race with high negative ratings across a large swath of the American public and news media.

Arguably, Clinton’s biggest error, however, was not personally campaigning in Wisconsin and Michigan in the final months of the campaign; and perhaps more critically, Clinton essentially took the month of August and a good part of September off from the campaign trail, only occasionally emerging at fundraisers. In that period, Trump was doing multiple campaign rallies a dayand saw his polling deficit to Clinton shrink from nearly eight points in early August to just one point in mid-September 2016, according to the RealClearPolitics poll averages.

There is no gentle way of saying this: Hillary Clinton was too inactive for too many long stretches in the campaign. But that will not be the case with the next Democratic nominee Trump faces.

Lastly, and most importantly, the U.S. has become a center-left country since the 2016 election and, with every day, a little bit bluer as Republicans disproportionately are dying off while identity groups associated with the Democrats are slowly growing in size.

The Democrats’ emerging majority through demographics thesis has been over-predicted by many social scientists and political pundits, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t happening in the long run.

Even if there is no deterministic relationship between vote choice and a person’s demographic characteristics, demographic trends are still in the Democrats’ favor.

Republicans can take some comfort in knowing political parties and people’s attitudes do change over time in predictable ways and only rarely has either major party been noncompetitive for long stretches of time. Political parties are strategic actors skilled at adjusting to changing electoral environments in order to remain relevant. It is a survival instinct.

Nonetheless, the following figures from Pew Research and the U.S. Census Bureau should keep RNC Chair Ronna McDaniel and Trump 2020 campaign manager Brad Parscale restless at night:

(1) “The Silent Generation (born 1928 to 1945) is the only generational group that has more GOP leaners and identifying voters than Democratic-oriented voters,” according to a 2017 study by Pew Research. “Democrats enjoy a 27-percentage-point advantage among Millennial voters (59% are Democrats or lean Democratic, 32% are Republican or lean Republican).”

Millennials account for 30 percent of the U.S. voting age population and is larger than the once dominant Baby Boomer generation.

If the GOP doesn’t become more competitive for Millennial support, the GOP will become the minority party at all levels of elected government in the next 10 years.

(2) Similarly, racial and ethnic divisions increasingly differentiate Republicans from Democrats, according to the Pew study, and the trends in this area favor the Democrats. “By more than two-to-one (63% to 28%), Hispanic voters are more likely to affiliate with or lean toward the Democratic Party than the GOP.” Trump made minor improvements among Hispanic voters when compared to Mitt Romney’s 2012 campaign, but hardly enough to suggest a trend favoring the GOP.

The Democratic advantage among Hispanics has been relatively stable. However, as a percentage of all Americans, Hispanic power is growing steadily and will be potentially decisive in every election hereafter. In 2014, Hispanics represented 17 percent of the U.S. population — in 2060, that number will be 29 percent, only 15 percentage points behind the non-Hispanic white population (44 percent).

In the future, it is hard imagine a successful Republican Party that hasn’t expanded its base to include more Hispanics and Millennials.

In the near-term, the Republicans are faced with a (likely) presidential candidate already skating on the thinnest of margins who must now navigate an even narrower path to victory.

The normal benefits of incumbency (money, agenda-setting powers, free media, policy victories) are muted by a unvaryingly hostile national news media (even Ann Coulter is calling Trump an ‘idiot’ these days). Where once a strong economy would make a president a sure bet for reelection, today, it has done little more for Trump than to prevent the bottom from dropping out of his approval ratings. Even a slight weakening in the economy could portend an election bloodbath against Trump on a scale similar to Reagan-Mondale.

Is Trump destined to lose in 2020? Not if the Democrats have anything to say about it…

The expectation here is that I will say something about how, if the Democrats move too far to the left, they risk what should be an easy victory in 2020.

That conclusion is not supported by the data.

Look again at Figure 4.

If anything, most of the voter segments are clustered in the ‘Democrat’ corner of the partisan attitudes index. It is not the Democrats most at risk of being ‘too extreme,’ it is the Republicans that are risking being relatively too extreme.

Independents are closer to Democratic positions than they are to Republican positions. Sure, that could change. I could imagine the Democrats pushing too hard on an issue where the American center is undecided (e.g., continuation of the current American wars in Syria and Afghanistan) and Trump using that issue to pull independents and ‘weak’ partisans back towards the GOP.

Voters, including independents and centrists, do not generally like vagueness coming out of the mouths of their politicians. That is why voters with otherwise moderate views will nonetheless prefer a candidate with strong partisan policy positions over a “centrist” candidate with views closer to their own. The research confirms this dynamic is not uncommon between voters and candidates. Distinctive candidates (and parties) attract voters.

And every election finds new issues (potentially important to voters) where candidates and parties can re-position themselves to become more distinctive and attractive. It is on these issues where the two parties subsequently skirmish to find the high ground position; and it is this strategic positioning that keeps the two parties competitive from one election to the next.

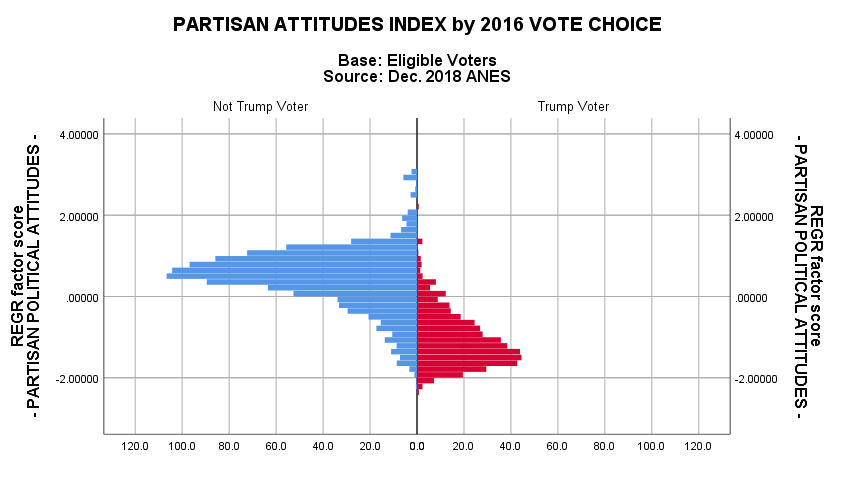

Figure 6: Partisan Attitudes by 2016 Vote Choice

Data Source: 2018 American National Election Study (Pilot); Analytics by Kent R. Kroeger

So while on most issues voters have sorted themselves out along partisan lines (see Figure 6 where positive values indicate ‘Democratic’ positions and negative values indicate ‘Republican’ positions), there are still many important issues where Americans have not yet picked sides. And these issues represent fertile battle spaces for strategic positioning by the parties looking for that next big electoral advantage.

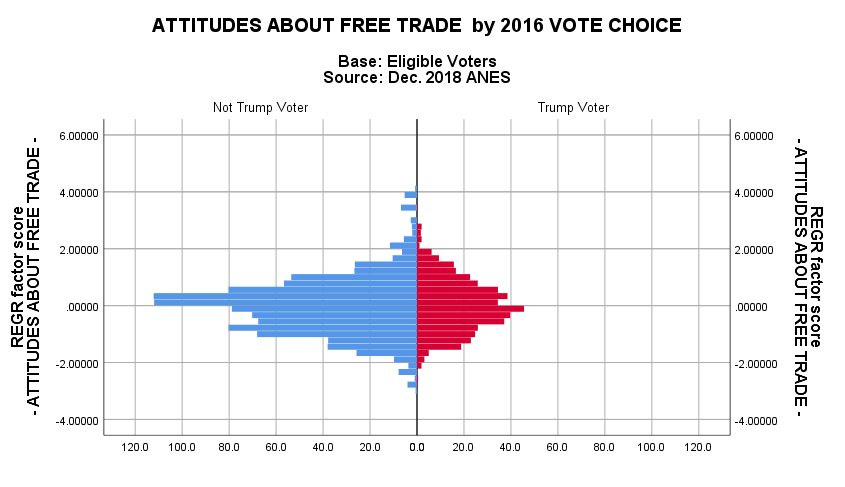

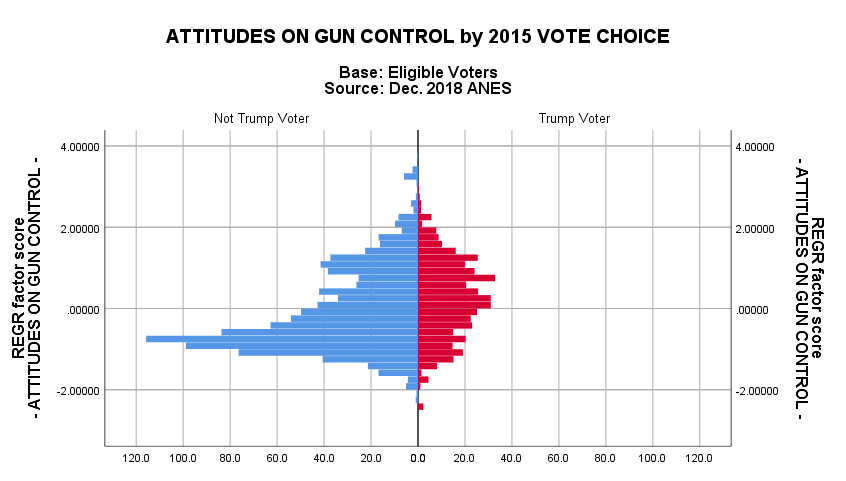

Here are just two examples: Free trade (Figure 7) and Gun control (Figure 8).

Given Trump’s populist takeover of the GOP, it should not surprise anyone that Republicans and Democrats are both divided on this issue — though that may change over time if Trump’s populism remains preeminent in the GOP. For now, free trade remains an issue where one party could still strategically position itself to attract a significant number of new or swing voters.

Figure 7: Attitudes about Free Trade by 2016 Vote Choice

Data Source: 2018 American National Election Study (Pilot); Analytics by Kent R. Kroeger

As for gun control, anyone that has lived in the Midwest knows Democrats own guns too and who doesn’t know a few Republicans that are staunch supporters of more restrictive gun control legislation.

Gun control remains a competitive theater of operations for Democrats and Republicans to prospect for new voters.

Figure 8: Attitudes about Gun Control by 2016 Vote Choice

Data Source: 2018 American National Election Study (Pilot); Analytics by Kent R. Kroeger

The point here is that the American political system, while too rigid in many ways such as the advantages afforded incumbents and the power of special interests to influence public policy, it is still a competitive, two-party system. It is presumptuous to claim either party has a permanent (or even growing) advantage in the voting booth. We are always just one or two elections away from power shifting in the U.S. House or presidency and there is nothing in the data to suggest that will change.

As for Trump, my original thesis that he has a market share problem still stands, but with one caveat. A clever politician (or party) faced with such a problem will look for ways to redefine the competitive space — to change the status quo in such a way that old partisan loyalties may become less relevant in the light of newer contingencies and considerations.

The de-nuclearization of North Korea? A peace treaty between Israel and the Palestinians? Brokering a summit and peace treaty between Iran, Israel and Saudi Arabia? A new era of Chinese-American economic cooperation built on a more equitable trade agreement? I don’t assume anything is impossible when it comes to Trump — no Democrat should.

That said, I’m not saying Trump is capable of being that creative either. He has shown no nimbleness in that regard as he continues to behave as if his biggest challenge is keeping his base supportive. Should someone close to him demonstrate the real problem — a lack of voters available to him in the political center — he might come up with a few surprises just in time for the 2020 election.

- K.R.K.

Please send cards and comments to: kroeger98@yahoo.com