By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, June 15, 2020)

There is no such thing as an attention span. There is only the quality of what you are viewing. This whole idea of an attention span is, I think, a misnomer. People have an infinite attention span if you are entertaining them.

Jerry Seinfeld

Whether comedian Jerry Seinfeld knew it or not, his quote on attention spans was touching one of the ongoing controversies in psychology and marketing science: Are people’s attention spans shrinking?

On the affirmative side is recent research by European researchers Philipp Lorenz-Spreen, Bjarke Mørch Mønsted, Philipp Hövel and Sune Lehmann who found that “the accelerating ups and downs of popular content are driven by increasing production and consumption of content, resulting in a more rapid exhaustion of limited attention resources. In the interplay with competition for novelty, this causes growing turnover rates and individual topics receiving shorter intervals of collective attention.”

Put more simply, in the era of social media and hyper-reactive media content, more competition for people’s finite brainspace is leading to people spending less time watching, reading and listening to specific topics.

If these researchers were to answer Seinfeld’s contention that people’s attention span expands to fit the quality (or novelty) of the content, they might reply: Yes, except that attention spans are actually bounded by time (i.e., we only have our lifetimes to consume content) and biology (i.e., its hard to listen to two people talking at the same time); and, in the internet-era, the increased competition for people’s attention has created more quality (or novel) content that attracts this attention.

In other words, higher quantities of compelling content is increasingly dividing up the finite pie of people’s attention into smaller segments.

So, perhaps, its not people’s attention span that has changed but, rather, the quantity of good content?

Research countering the ‘shrinking attention span’ argument was animated by this question: How is that people can’t pay attention during a 1-hour business meeting but can willingly do a 6-hour binge watch of Game of Thrones or Supergirl?

Using public opinion survey data, researchers at Prezi, a business presentation software company, and Kelton Research, a consumer research company, found in a 2018 study that attention spans are actually improving over time, not decreasing, and that people are, instead, more selective about the content they consume.

“Respondents claimed their ability to maintain focus has actually improved over time, despite an ever-growing mountain of available content,” argue the Prezi and Kelton Research report authors. “And it makes sense if you think about it: many of us have become more selective about what we give our attention to, bookmark things to return to when nothing else piques our interest, and often prefer to wait for good content to find us rather than seek it out ourselves.”

In a more academic rebuttal to the ‘shrinking attention span’ argument, Dr. Gemma Briggs, a psychology lecturer at the Open University (Milton Keynes, UK), contends that attention span is task-dependent. “How much attention we apply to a task will vary depending on what the task demand is,” says Dr. Briggs.

According to Dr. Briggs, its not declining attention spans driving down our attention to specific topics, its that content providers are better at grabbing our attention. [This could also explain why I’m on my third marriage.]

Declining media and public interest in the coronavirus pandemic

The current coronavirus pandemic is stark evidence at how hard it is to keep people’s attention.

Imagine a global crisis spanning over six months in which eight million people are directly impacted and nearly a half million people perish from its effects. Add to that the billions of people indirectly affected by its economic consequences. That should grab everyone’s attention, right?

Yes, it did. And then some.

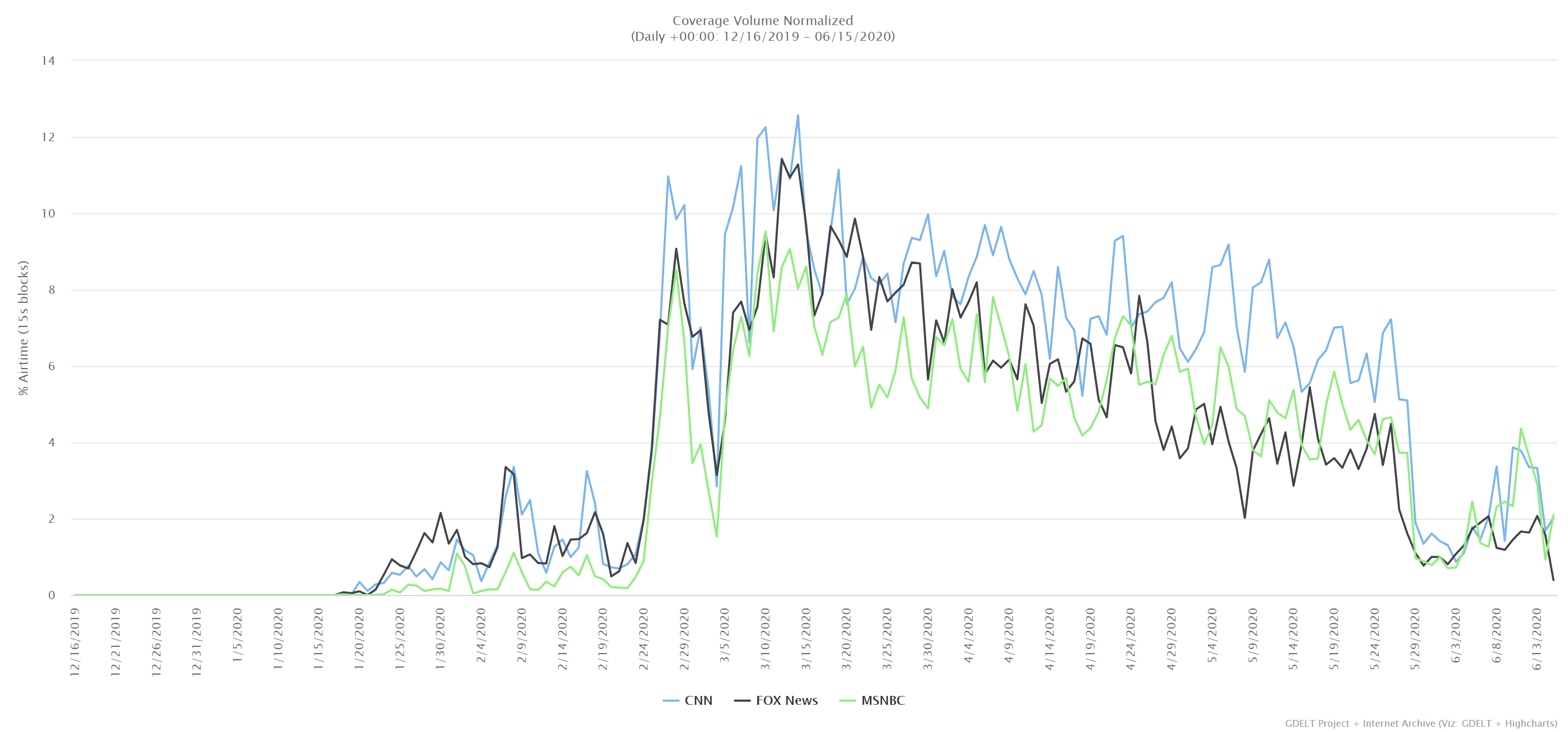

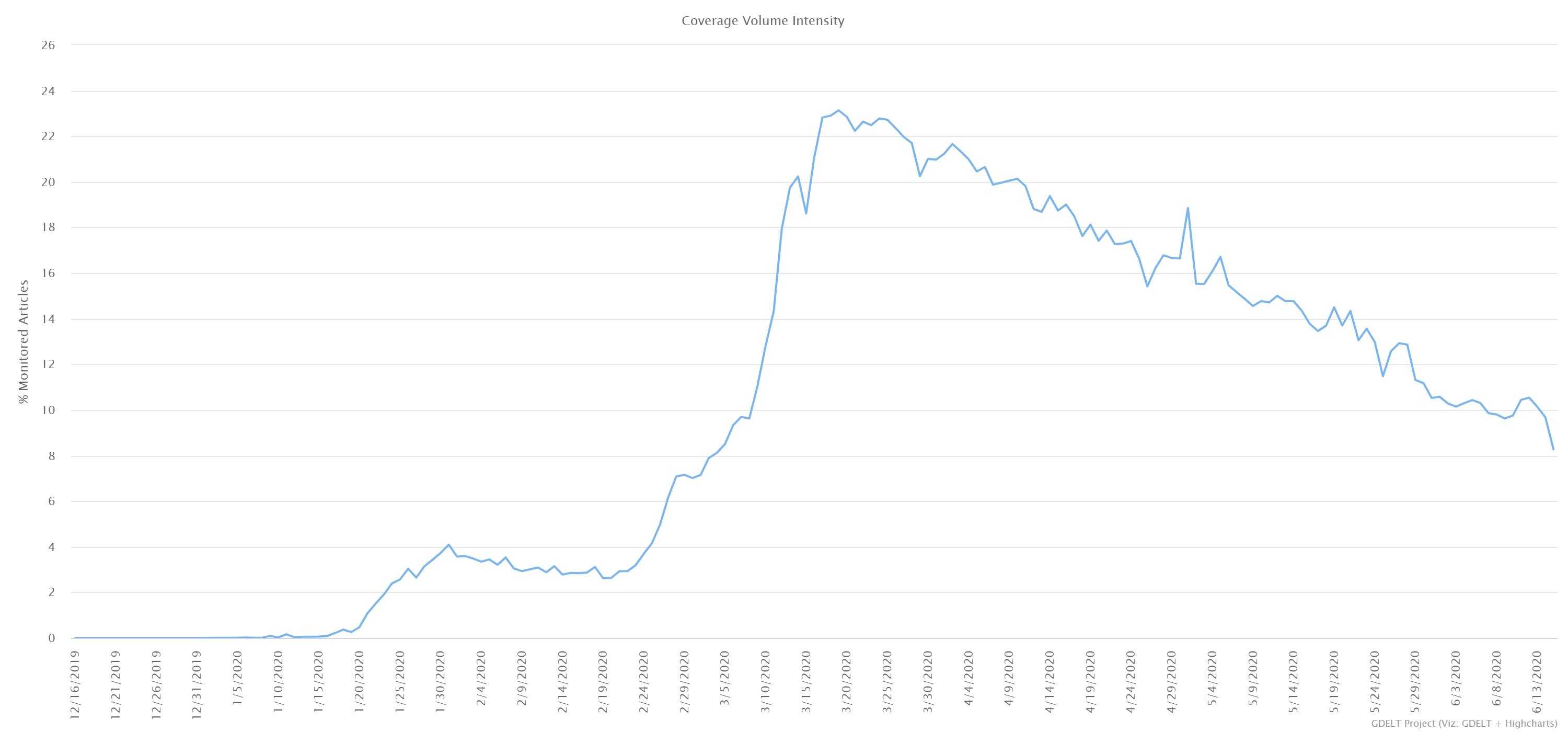

Coverage of the coronavirus pandemic flourished within U.S. cable TV news and on internet news sites from late-February to late-May (see Figures 1 and 2, respectively), peaking in mid-March when most U.S. states issued lockdown orders to combat the virus’ spread, but declining steadily thereafter until late-May when George Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis, Minnesota police officers quickly rose to the top of the news agenda (see Figure 3).

Figure 1: U.S. Cable TV news coverage of the coronavirus pandemic

Figure 2: Online news coverage of the coronavirus pandemic

Figure 3: U.S. Cable TV news coverage of George Floyd’s death

But those three graphs represent the news media’s attention. What about the public’s attention?

Google Trends tracks how often people Google-search on a specific topic and therefore is often used by researchers as a proxy for public interest. Figure 4 shows five search terms and the relative frequency each has been searched since January 1st.

Figure 4: Google searches on coronavirus, weather, COVID-19, George Floyd and Black Lives Matter from January 1 to June 14, 2020.

Like the news coverage, the public’s interest in the coronavirus/COVID-19 peaked in mid-March with the first statewide lockdowns and has been in a steady decline since then, being matched by searches on ‘weather’ after May 21st and by the combined searches on George Floyd and Black Lives Matter from May 27th to June 6th.

Part of that decline in searches on ‘coronavirus’ could reflect people using Google as a basic education source, not just a news source. Once people acquire sufficient information on a topic, their use of Google’s search engine on the topic may also decline. Perhaps this apparent decline in interest is not as substantial as it looks in Google Trends.

However, research as shown Google search frequency is a useful indicator of public interest and relatively accurate predictive tool. For example, Google searches for upcoming movies, political candidates and specific vehicle brands and models are predictive of movie box office receipts, candidate vote shares and vehicle sales.

Assuming, therefore, that this decline in public interest in the coronavirus is genuine, what has caused it?

Possible Reason #1: People have shorter attention spans

Possible Reason #2: More compelling events (e.g., the 2020 Election, George Floyd, Black Lives Matter) have replaced the pandemic in people’s minds

I’ve already discussed these two possible explanations in the above discussion about attention spans and the importance of compelling content in keeping people engaged.

These potential reasons are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Both could be factors in the coronavirus interest decline.

But there are other possible causal factors to consider…

Possible Reason #3: Public interest follows the news media’s interest

Insight is gained when Google-search data on the coronavirus is overlaid with the cable TV news data (see Figures 1 and 4 above). The two data series track closely together, with a Granger causality test indicating changes in cable TV news coverage are more predictive of changes in public interest (Google-search behavior) than the other way around.

In fact, there is a large amount of media and public agenda-setting research linking changes in public attitudes and beliefs to changes in media coverage (and vice versa).

In their meta-analysis of the news media’s public agenda-setting effects from 1972 to 2015, Yunjuan Luo, Hansel Burley, Alexander Moe, and Mingxiao Sui found a “consistency in findings across agenda-setting studies and the presence of strong news media’s public agenda-setting effects.”

Therefore, it is reasonable to conjecture that one possible cause of the U.S. public losing interest in the coronavirus is its declining priority within the news media.

Possible Reason #4: The coronavirus pandemic is in decline

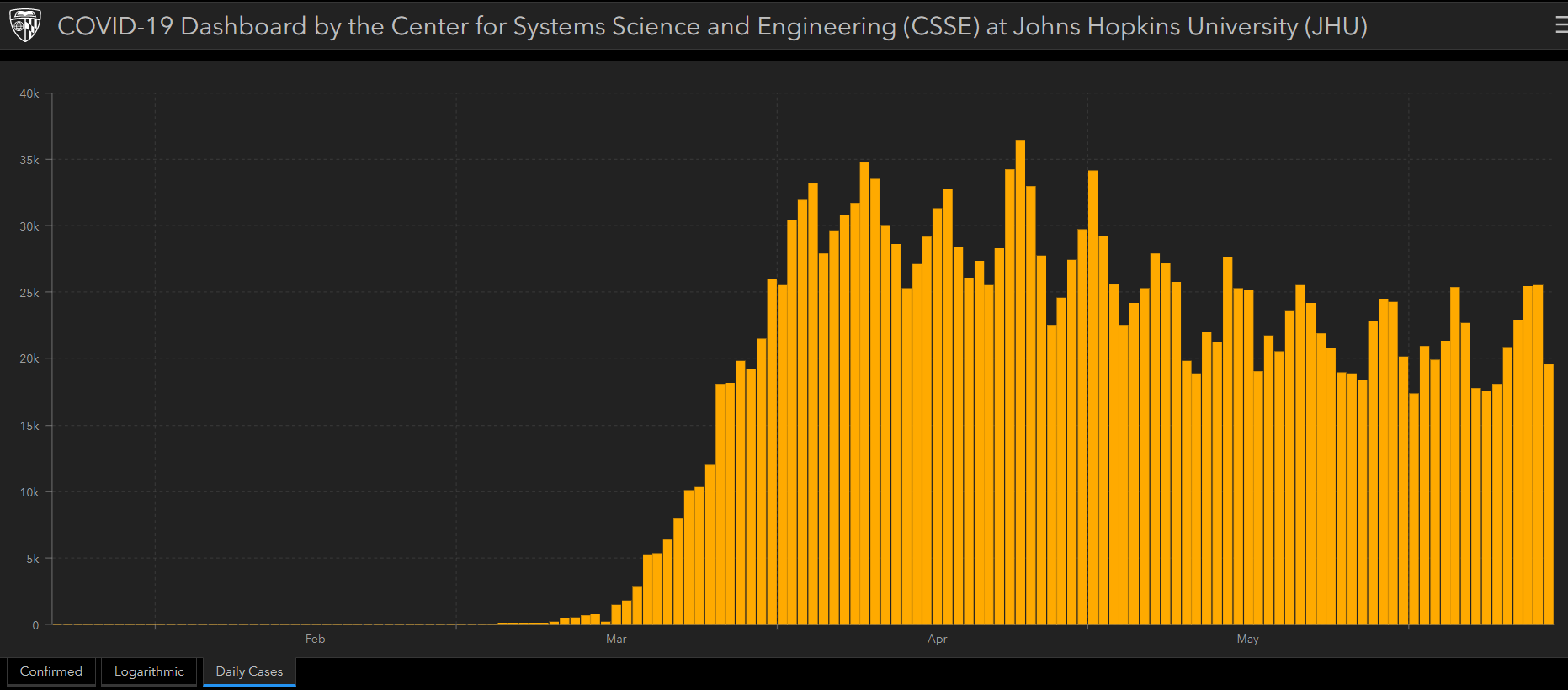

Could the objective decline in the coronavirus pandemic explain the falling interest by both the news media and the public?

This possible reason seems implausible to me.

While the U.S. is off its pandemic peaks, the number of daily new U.S. cases has only fallen 30 percent from its high on April 24th (see Figure 5) and 23 U.S. states are still experiencing increasing infection rates. Meanwhile, worldwide, the coronavirus pandemic is still growing, particularly in countries in South and Central America where a significant percentage of Americans were born or have family still living there (see Figure 6).

Figure 5: U.S. New Daily Coronavirus Cases (Jan. 22 to June 14, 2020)

Figure 6: Worldwide New Daily Coronavirus Cases (Jan. 22 to June 14, 2020)

To my eyes, the coronavirus pandemic has not declined anywhere near the magnitude of the decline in interest. It could be a contributing factor, but it doesn’t seem likely that this is the primary cause.

Possible Reason #5: Americans are weary of negative news

In a November 2019 survey of more than 12,000 U.S. adults, Pew Research documented a high level of ‘negative news fatigue’ by Americans.

“About two-thirds of Americans (66%) feel worn out by the amount of news there is, while far fewer (32%) say they like the amount of news they are getting,” says senior researcher Jeffrey Gottfried. “Americans’ exhaustion with the news hasn’t changed since early 2018 — the last time the (Pew) Center asked this question — when 68% felt worn out. And in a similar question asked several months before the 2016 presidential election between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, nearly six-in-ten (59%) felt worn out by the amount of coverage of the campaign and candidates.”

It is certainly plausible that the profoundly negative, life-threatening aspects of the pandemic has made it a tough topic for Americans to sustain their unbroken attention.

Sometimes you just need to look away.

The coronavirus pandemic has produced an unprecedented level of public interest, even if that interest has since softened

Google searches on the coronavirus reached unprecedented levels in the U.S. and across the globe in March and April.

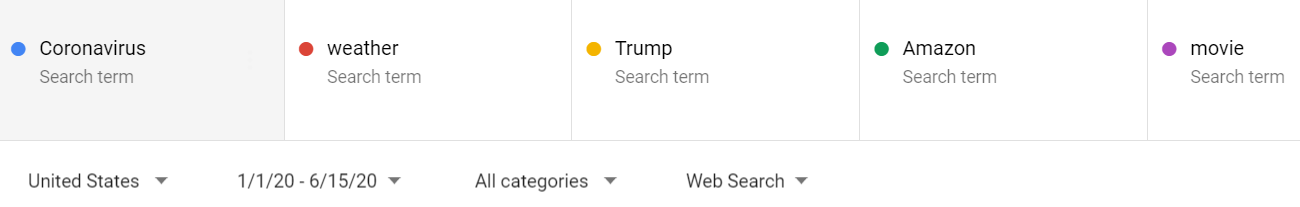

Figure 7 shows Google search trends in the U.S. from January 1st to June 15th for the term ‘coronavirus’ in comparison to other common search terms: weather, Trump, Amazon, movie.

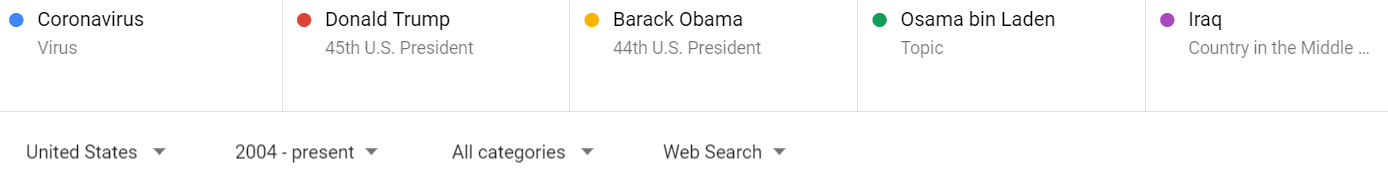

Figure 8, in turn, shows Google search trends since 2004 for the U.S. presidents and the Iraq War.

Figure 7: Comparing Google searches on the ‘coronavirus’ to other common search terms

Figure 8: Comparing Google searches on the ‘coronavirus’ to the past three U.S. presidents and the Iraq War (2004 to present)

The coronavirus towers over everyone and everything else. So much so that the effectiveness of online advertising significantly changed soon after the pandemic became the dominant U.S. news story.

One of the most important measures in website analytics and digital advertising is the conversion rate — which is the proportion of website visitors who take action beyond simply viewing its content, such as clicking on a banner ad or responding to a direct request from a content creator.

According to digital advertising expert Mark Irvine, after it was clear in mid-March that COVID-19 was a massive epidemic in the U.S., conversion rates dropped by an average of 21 percent in just three weeks.

So, yes, interest has waned since the peak in April, but it is still relatively high compared to terms that are typically in the Top 10 of Google searches on an average day.

Even so, the declining Google-search interest in the coronavirus since March is significant and sustained and matched by a similar decline in the news media.

Understanding why this has occurred despite the ongoing nature of the crisis — and at such a fast rate nonetheless — should be fertile ground for research far into the future.

Final thoughts

I left one possible explanation for this coronavirus interest decline out of the above discussion, in part, because it is more of a corollary to Possible Reason #3 (Public interest follows media interest). There is no question that the world economy has contracted due to the coronavirus pandemic. The U.S. is now officially in a recession, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research. Thus, there is an economic incentive for economic and incumbent political elites to desire moving past this worldwide health crisis. To dwell on it longer than necessary can only hurt the economy further.

Is it possible economic or political elites have actively seeded the news media — particularly the corporate-controlled news media (Is there any other kind in the U.S.?) — with stories and agendas designed to cast attention away from the coronavirus pandemic?

I do not possess any evidence to suggest this has happened, but I won’t rule it out.

- K.R.K.

Send comments and suggestions to: kroeger98@yahoo.com

Or tweet me at: @KRobertKroeger1