__________________________________________________________________

This is the first essay in a series dedicated to analyzing the U.S. eligible-voter population using the 2018 American National Election Study (ANES), an online survey administered in Dec. 2018 by researchers from the Univ. of Michigan and Stanford Univ.

__________________________________________________________________

By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; March 8, 2019)

Most everything we know about the Democratic Party and its supporters may be wrong or distorted.

As an example, while New York Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez may be the fastest rising star in the party’s progressive wing, she is not representative of the typical progressive, at least not demographically.

Democratic Party progressives are more likely to be white, educated, wealthy and older, according to the 2018 American National Election Study (ANES).

Democrat centrists, in contrast, are more likely to be African-American or Hispanic, and are less educated, less wealthy and younger. In other words, on average, they look more like Ocasio-Cortez than Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar.

This common disconnect, frequently found in media narratives on the Democratic Party’s ideological divisions, stems from the news media’s bias towards covering elites, as opposed to actual voters. This essay will hopefully fill in some of the knowledge gaps arising from this pervasive bias.

Using data from the 2018 ANES, a survey administered by The University of Michigan and Stanford University in December 2018 to a nationally representative sample of eligible U.S. voters, the following analysis investigates the country’s major political fault lines and their potential impact on the 2020 election.

The eligible voter segments in the U.S.

Here is the biggest assumption circulating among political operatives and pundits today: The Democratic Party is deeply divided between a centrist, more free market-oriented faction, often associated with former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and current Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, and a younger, more idealistic faction, represented by politicians such as Ocasio-Cortez, California Rep. Ro Khanna and Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders.

This description of Democrat partisans may work in describing divisions within Democratic elites, but says little about what is going on at the voter level.

Lets start with the issues that best defined the eligible voter segments…

A segmentation of U.S. eligible voters created from the issue-related questions in the 2018 ANES (see Appendix below for the question list) identified five population segments: Democrat Progressives (30% of eligible voters), Democrat Centrists (16%), Independents (19%), GOP Centrists (8%), and the GOP Base (27%). This segmentation clustered eligible voters based strictly on their opinions regarding a wide range of political, social and economic issues, including immigration, health care policy, income inequality, taxation, global warming, gun control, trade policy, and the opioid crisis.

Two policy issues in particular distinguished Democrat Progressives from the GOP Base: attitudes on health care and immigration. More than any other eligible voter segment, Democrat Progressives support the Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) and oppose Donald Trump’s border wall (see Figure 1 below). In stark opposition is the GOP Base, which stands alone in its support for the wall and opposition to the 2010 ACA. And in the middle are partisan Centrists and Independents, collectively representing 43 percent of eligible voters.

Figure 1: Attitudes on health care and immigration divide partisansData Source: 2018 American National Election Study (Pilot); Analytics and Segmentation by Kent R. Kroeger

Along with the isolation of the two party bases, the other noticeable feature from Figure 1 is the large political center — a proportion of the total population (43%) more than capable of tilting the advantage in one party’s favor during any given election. Any suggestion otherwise is rubbish. The center still matters. And, yes, they do vote — though not at the same rate as the strong political partisans.

As Figure 2 shows, the party bases are highly divided on climate change as well. Almost every Democrat Progressive in the 2018 ANES said the U.S. should be doing more on climate change (99%), while only 13 percent of the GOP Base held the same view. In contrast, opinions on free trade agreements do not divide the party bases, where both generally support free trade (though they may have different approaches for getting there). It is the political center demonstrating the most skepticism on free trade agreements — which may be indicative of the center’s relative youth and economic vulnerability.

Figure 2: Attitudes on free trade and climate changeData Source: 2018 American National Election Study (Pilot); Analytics and Segmentation by Kent R. Kroeger

Demographic differences across the eligible voter segments

In some cases, the demographic variation in the eligible voter segments may elicit some surprise. But not when it comes to describing the GOP Base, whichstands alone as predominately white and male (see Figure 3). Every other segment is majority female, including GOP Centrists, where nearly 60 percent are female, a higher percentage than any other segment. In fact, GOP Centristsare predominately young, white females and represent, arguably, the party’s greatest strategic weakness heading into the 2020 campaign.

The most ethnically diverse segments are Democrat Centrists (30 percent African American, 22 percent Hispanic, and 5 percent Asian) and Independents (13 percent African American, 23 percent Hispanic and 6 percent Asian).

After the GOP Base, Democrat Progressives and GOP Centrists are the least ethnically diverse.

Figure 3: Sex and race differences across the eligible voter segmentsData Source: 2018 American National Election Study (Pilot); Analytics and Segmentation by Kent R. Kroeger

Indeed, a simplified description of Democrat Progressives might be to call them rich, middle-aged, educated, white people (see Figures 4 and 5). They are the second oldest and wealthiest segment, after the GOP Base, and the most educated.

Centrists and Independents are equally distinctive in the other direction: poorer, younger and less educated.

Figure 4: Income and education differences across the eligible voter segmentsData Source: 2018 American National Election Study (Pilot); Analytics and Segmentation by Kent R. Kroeger

Figure 5: Income and age differences across the eligible voter segmentsData Source: 2018 American National Election Study (Pilot); Analytics and Segmentation by Kent R. Kroeger

That Centrists and Independents share these features should not be surprising, as younger and less educated voters tend to possess weaker partisan ties (which will increase as they age and become more educated and prosperous).

Of course, there are young activists who are highly partisan and they tend to be visible. But that is precisely why the bias persists in the media about millennials being ardent progressives. The average millennial, however, is not. Only 26 percent of millennials (30 years-old or younger) are Democrat Progressives. The majority are Centrists (29%) or Independents (24%).

Now for the big surprise…

Is Bernie Sanders’ viability driven by the Democratic Party’s far left?

The overwhelming assumption among political pundits is that Bernie Sanders remains competitive in the Democratic presidential nomination race because he is sustained by the Democratic Party’s far left.

This is not true. Not even a little bit true.

First, it is important to remind ourselves that a candidate’s policy positions does not necessarily reflect the opinions of a majority of their supporters.

And before you reply with — “Of course they do” — consider this:

As many Bernie Sanders supporters are…wait for it…Centrists and Independents (55% combined) as they are Democrat Progressives (44%)!

This is not news. If anything, he over-performs among Centrists and Independents. This has been known since the 2016 election. In part, this is driven by name recognition, particularly among Centrists, who tend not be as politically active or informed as Democratic Progressives.

Within Democrat Progressives, Sanders polled third (17%), behind Joe Biden (30%) and Beto O’Rourke (21%) in the Dec. 2018 survey (see Figure 6). Among Democrat Centrists (see Figure 7), Sanders attracted 30 percent support (a statistically significant difference from his support among Democrat Progressives). Sanders, in fact, is tied with Biden among Independents intending to vote in a Democratic primary in 2020 (see Figure 8).

Figure 6: Preferred Democratic presidential nominee among Democrat ProgressivesData Source: 2018 American National Election Study (Pilot); Analytics and Segmentation by Kent R. Kroeger

Figure 7: Preferred Democratic presidential nominee among Democrat CentristsData Source: 2018 American National Election Study (Pilot); Analytics and Segmentation by Kent R. Kroeger

Figure 8: Preferred Democratic presidential nominee among IndependentsData Source: 2018 American National Election Study (Pilot); Analytics and Segmentation by Kent R. Kroeger

Is it possible Bernie Sanders will pull Centrists and Independents towards the left as many continue to support him in 2020? An interesting question for a panel design study to investigate. Unfortunately, we can’t say that is true based on the cross-sectional data from the 2018 ANES.

However, we do see stark differences across the five segments in how they rate specific identity groups, movements and economic ideologies (see Figures 9 through 11). This patterns lends some credibility to the argument that Sanders’ attraction to Centrists and Independents up to now has been driven in part by his lower emphasis on identity group politics.

But this may be changing for the 2020 campaign based on Sanders’ recent candidacy announcement speech. If his stump speech emphasis does change, it will be interesting to see if Sanders-supporting Centrists and Independents align their views of various identity groups and movements with the party’s progressive wing. It seems odd to say this, but Sanders may lose his moderate base in the Democratic Party if he moves too far to the social issue left in the 2020 campaign.

As of December 2018, Centrists and Independents have very different group affinities when compared to Democrat Progressives. For example, where, on average, Democrat Progressives rate the #MeToo movement as an 80 (on a 0 to 100 scale), Democrat Centrists rate it a 58 and Independents a 47 (see Figure 9). All statistically significant differences.

Figure 9: How factions rate the #MeToo movement and the TransgenderData Source: 2018 American National Election Study (Pilot); Analytics and Segmentation by Kent R. Kroeger

A similar pattern exists for how the segments rate transgender Americans, the alt-Right movement, and antifa (see Figures 9 and 10).

Figure 10: How factions rate the alt-Right movement and antifaData Source: 2018 American National Election Study (Pilot); Analytics and Segmentation by Kent R. Kroeger

Finally, one of the more interesting relationships in the 2018 ANES data is how the segments rate socialists and capitalists (see Figure 11). All segments — less the GOP Base — rate capitalists below 50, on average. Whereas, ratings of socialists follow the more typical pattern, with Centrists and Independents coming somewhere near the midpoint between the GOP Base and Democrat Progressives. However, only the Democrat Progressives, on average, rate socialists above 50. Even Sanders’ Democrat Centrist supporters rate socialists below 50, on average.

Figure 11: How factions rate Socialists and CapitalistsData Source: 2018 American National Election Study (Pilot); Analytics and Segmentation by Kent R. Kroeger

Final thoughts

If all we did was consume cable network news and mainstream print media for our political coverage, a biased picture of the American electorate might form. The news media sees a highly polarized American voting population — half still fuming over the 2016 election outcome — that has abandoned the political center for the more organized (and entertaining) partisan camps.

Politics has become even more tribal — or so we are told.

Unfortunately, this narrative falsely characterizes Americans’ political lives. The political center, while smaller than in the past, is alive and well and very relevant to electoral outcomes in this country. The 2018 ANES data finds at least 40 percent of eligible voters somewhere in the political middle.

Still, this faulty chronicle laid out daily for Americans is not borne from a news media wanting to misrepresent reality, but from the market’s demand for engaging, consistent narratives — often lazy and inaccurate in practice — repeated over time in pursuit of larger audiences. And larger audiences increase ad revenues which increase the probability of higher profits.

Its not a crime. Its all good capitalism.

Nowhere is this bias more apparent than how the news media covers the Democratic Party. The narrative goes something like this: The young, progressive left — represented by Ocasio-Cortez’ youthful arrogance and Sanders’ relatable (but dreamy) brand of socialism — versus the sober party centrists like Nancy Pelosi, Hillary Clinton, Joe Biden and Chuck Schumer, who put an emphasis on ‘getting things done.’

Progressives equate to dynamic and creative. Centrists equate to steady and pragmatic. The narrative is not completely wrong — but it is dangerously misleading given what we know about voters and how well they align with this narrative.

Most progressives in the Democratic Party don’t look like Ocasio-Cortez. They are white, middle-aged, (over) educated, and relatively wealthy. And, as for Sanders’ ongoing quixotic quest for the presidency, if it is to succeed, it will be built as much around the Democratic Party’s centrist wing as it will around its progressive wing.

That is not the story we are generally hearing in the news media. And don’t expect to hear it anytime soon.

- K.R.K.

Data and SPSS computer codes are available upon request to: kroeger98@yahoo.com

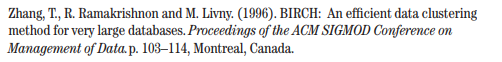

APPENDIX:

In developing the segmentation of eligible voters in the 2018 ANES, I used SPSS’ proprietary TwoStep clustering algorithm.

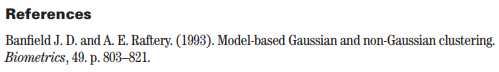

The SPSS TwoStep clustering procedure can handle both continuous and categorical variables by extending the model-based distance measure used by Banfield and Raftery (1993) and utilizes a two-step clustering approach similar to BIRCH (Zhang et al. 1996).

Below is the list of 2018 ANES questions used to create the eligible voter segmentation:

All variables were treated as continuous variables and standardized within the two-step clustering procedure.