By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, April 11, 2018)

{Feel free to send any comments about this essay to: kkroeger@nuqum.com}

[This essay is in two parts: Part 1 examines the effect of today’s hyper-partisanship on Americans; Part 2 details some simple steps to recover from hyper-partisanship]

Our political system is broken. Not exactly a new observation, but it can’t be repeated often enough.

Our political system is broken.

Nothing gets solved anymore. Problems get pushed down the road, real people suffer, and our media stars make seven-figure salaries stewing about it as they preen before TV cameras.

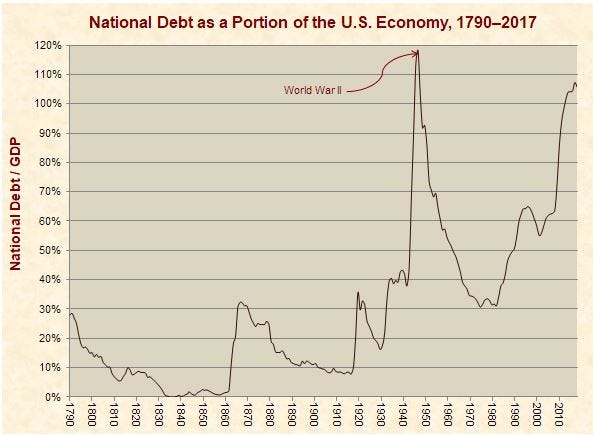

And while we are all distracted by their self-promoting piety, we fail to notice our country’s debt recently passed the $21 trillion mark. Our national debt as a percentage of the economy now approaches levels only seen during World War II.

We were fighting in Europe, Africa, and Asia in 1944. Taking on some debt in the service of defending the world from fascism is understandable. Today, however, we are not fighting two of the biggest military powers in the world. Our typical enemy combatants anymore don’t even have navies or air forces and they number in the thousands, not millions.

You would think our national dialogue right now would be laser-focused on whether we can afford an over $700 billion annual defense budget.

But, alas, according to the cable news networks, we have bigger issues to worry about. Or, rather, two big issues: Stormy Daniels.

Or whatever else is orbiting Planet Trump on a given day.

This isn’t going to end well for any of us, regardless of party or ideological preference. The Trump-Russia obsession is making both political parties look feckless and intellectually sterile (They were long before Donald Trump, by the way). In Noam Chomsky’s words, “Russia hysteria is making the U.S. an international laughing stock.”

I blame hyper-partisanship, which predates the current presidency. And even though this phenomenon may be a symptom rather than a cause, it is certainly not working towards the public good.

Hyper-partisanship amplifies social problems yet prevents the solutions

Hyper-partisanship gives us the worst-of-all-possible worlds: it amplifies societal problems and then serves as the major impediment to enacting any solutions. The partisan divide in this country has risen to a such degree that it has become toxic to our basic social institutions.

Yet, for all pundit chatter about today’s extreme partisanship, there is no serious social movement attempting to repair this damage to our political culture.

If you think Donald Trump and the Republicans are the cause of our dysfunctional political system, you will be disappointed when the national dialogue doesn’t improve under President Kamala Harris and a Democrat-controlled Congress.

The problem is not politicians. The problem is us.

Hyper-partisanship gnaws at the foundations of collective action.

Empirical evidence is building that excessive partisanship in our daily lives is causing increased levels of stress at work and home. In an opinion poll conducted by the American Psychological Association last year, just over half of Americans (57%) said that the current political climate was a “very” or “somewhat” significant source of stress in their lives. This level of stress was even higher among Democrats (72%), for obvious reasons.

Self-reported stress measures are correlated with individual-level physiological stress indicators which medical research informs us can shrink our brains, lower our IQ (at least temporarily), increase heart disease, and wreck our personal relationships.

Hyper-partisanship may be destroying us physically.

At a societal-level, an increase in political polarization corresponds to a geographic polarization with liberals clustering in urban areas and coastal regions, and conservatives living in rural areas and middle America.

Geographic clustering is consequential as it has led to more ideologically homogeneous congressional districts, making it harder to find electorally competitive districts. Over time, as the electorate has polarized along geographic and ideological lines, the number of competitive U.S. House races has been in decline.

Only 40 of the 435 seats in the U.S. House were considered competitive heading into the 2016 election, according to David Wasserman, an analyst for the non-partisan Cook Political Report in Washington. In contrast, in the 2010 U.S. House elections, over 100 seats were considered competitive just before Election Day.

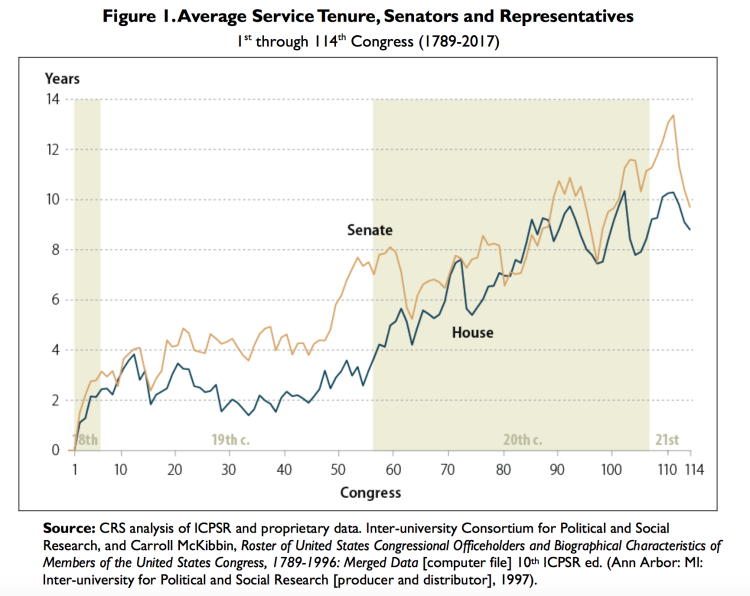

While the 2018 U.S. House elections are looking more competitive with 50 races being classified as competitive by 270ToWin.com, when considering the average tenure of U.S. House or Senate members, our current legislators are near record-breaking levels for average length of tenure (see chart below).

The result of this polarization is a political system less responsive to voters. From a policy output perspective, the politicians elected from increasingly ideological polarized districts are less likely to be ideologically “moderate” and less willing to compromise on policy when they enter state and national legislatures.

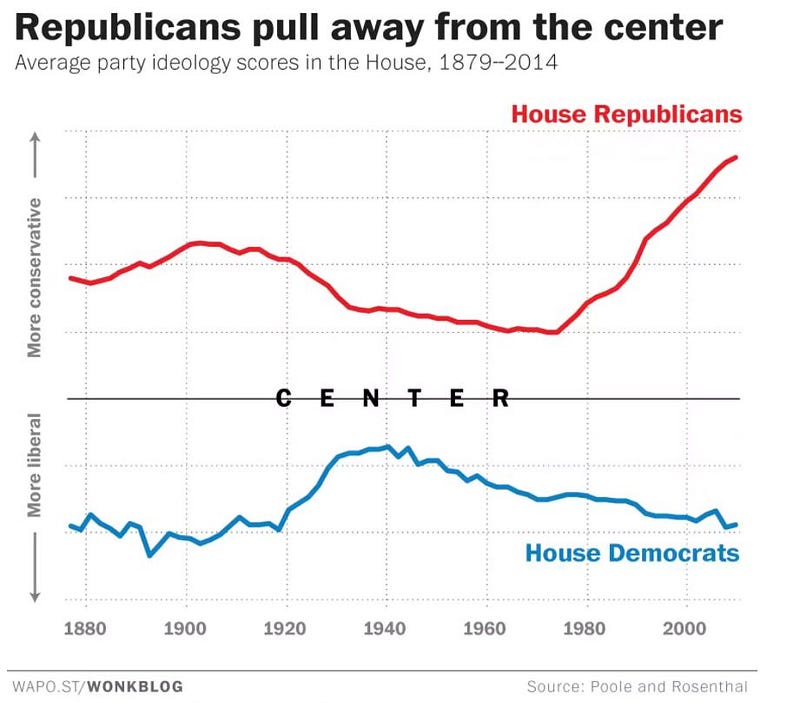

The loss of “moderates” in the U.S. House has been especially dramatic among Republicans (see chart below), who started their ideological long march from the center just prior to the election of Ronald Reagan’s in 1980.

In terms of actual policy output, the last three congressional sessions witnessed near record lows in the amount of legislation passed each session (Perhaps that is a good thing…don’t we have enough laws already?).

A polarized American electorate is not simply a psychometric phenomenon, but a social one that has led to tangible changes in this country that will be hard to reverse. Our political system is more rigid, unresponsive, and less productive. In good economic times, many could argue we don’t need an activist government passing large numbers of laws. But there will be economic downturns in the future when we will require an engaged, responsive and productive Congress — — the question is: will our political system be ready when it is called upon to do its job.

What are the barriers to partisan detoxification?

If we are to reduce the electorate’s polarization, we will need to understand the many aspects of human psychology that foster hyper-partisanship and become barriers to its reversal.

The biggest barriers may be the hardest to change: our general lack of self-awareness, fragile egos, imperfect ability to empathize with others, and basic physiological need for companionship.

Taken together, our human flaws conspire against our ability to open our lives and minds to new ideas and alternative points of view.

For example, on average, we think we are smarter and better-looking than any objective measure would indicate. Human conceit may be a constant through history, but with the rise of social media these psychological frailties can distend into narcissism and other forms of self-absorption.

Social media is now the primary news source for 60 percent of Americans and its effect on the electorate may be central to understanding recent trends in political polarization. But it may also be leading to other negative outcomes in the electorate.

Dr. Larry Rosen, professor of psychology at California State University, presented study results at the 2011 annual convention of the American Psychological Association showing how teens who spend more time on Facebook are more likely to show narcissistic tendencies and other behavioral problems (such as low academic performance).

A 2010 study of Facebook users from ages 18 to 25, conducted at York University (Canada), assessed the subjects on the Narcissism Personality Inventory and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. The researchers also measured each subject’s level of ‘self-promotion’ on their Facebook pages, defined as updating their status every five minutes, frequent posting of pictures of themselves, photos of celebrity look-alikes, and quotes and mottos glorifying themselves. The researchers concluded that the people who used Facebook the most for self-promotion tended to have narcissistic or insecure personalities.

Neither of these studies prove that frequent use of social media sites causeincreased levels of narcissism, but they do suggest a strong link between social media use and various personality disorders.

Additionally, studies have shown that social media use can limit the breadth of our information sources and reduce our exposure to other points of view. If true, that is a toxic outcome for a democracy.

Ashik Shafi (Bethany College) and Fred Vultee (Wayne State University), in their analysis of a 2014 survey of students at a large Midwestern university, found that “social media use negatively predicts respondents’ knowledge about political processes, institutions and current events when other possible predictors of political knowledge are controlled.”

While their study does not prove a causal link between social media use and political knowledge, it does suggest social media may negatively impact users’ political knowledge through two mechanisms: (1) information filters — where social media allows users to systematically filter out specific sources of political information, and (2) time replacement — where the time people spend on social media replaces time they would have spent engaging in social activities in the meatsphere (real-life).

This process mirrors Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam’s ‘bowling alone’ thesis that explained Americans’ declining participation in social activities, such as bowling and political activism, by their increased time watching television.

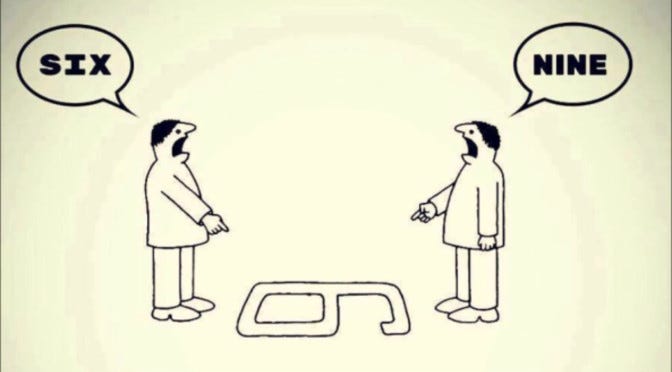

Through social media, we create personalized echo chambers that reinforce our existing opinions, resulting in increasingly intransigent opinions vis-a-vis other opinions in the world we purposely tune out of our Facebook news feeds and posts.

Social media narrows our knowledge base and filters out evidence of our own fallibility, creating a feedback loop that inflates confidence in our own capacity to comprehend complex social phenomena. This feedback loop limits our exposure to divergent opinions and maximizes inputs from like-minded people, thereby reinforcing our existing partisan biases. The more we personalize our media choices, the more partisan we become.

Social media has turned us all into thinking we are PhD. sociologists and economists and, subsequently, less willing to consider opinions and ideas from actual PhD. sociologists and economists.

Political scientists that study ‘media effects’ refer to the partisan selective exposure among information seekers to explain the potential effects of social media on political partisanship and ideology. In other words, we avoid information that might contradict our existing opinions and seek out information that confirms them. Political scientists W. Lance Bennett and Shanto Iyengar call this ‘individualized reality construction’ — — and it may not be a good thing for sustaining a healthy, constructive political culture.

The rise of social media (and individualized reality construction) has also coincided with a demise of the inadvertent audience.

“During the heyday of network news, when the combined audience for the three evening newscasts exceeded 70 million, many Americans were exposed to the news as a simple byproduct of their loyalty to the sitcom or other entertainment program that immediately followed the news,” according to Bennett and Iyengar. “It is likely that this ‘inadvertent’ audience may have accounted for half the total audience for network news.”

During the peak audience years for broadcast network television, a significant percentage of Americans were exposed to news and political information that they would not have sought out on their own. One result of this large ‘inadvertent audience’ may have been that it helped build a national political culture where people, regardless of political orientation, shared the same information sources.

Social media may be eroding mass media’s function as a cultural bonding agent and replaced it with an information environment that now divides us more than unite us. We can delude ourselves into thinking our 1,000+Facebook friends actually measures something good about us, but it may indicate something much more privative.

Along with our new social media-driven echo chambers, there are two other flaws in our neuro-cognitive biochemistry that deserve mentioning and that may stunt any attempt to open our minds to new opinions and ideas.

We are often bad at making predictions…

If we are honest with ourselves, we realize most of our personal predictions never come true. In fact, psychological research on generalized anxiety disorder has found that more than 80 percent of our negative predictions never materialize. And even when these predictions do occur, the consequences are often far less serious than we had previously imagined. Nonetheless, the anticipation of negative events cause levels of stress that can drive us deeper into the dark dynamics of individualized reality construction.

Most of what we believe as fact is, in truth, wrong…

In addition to our attraction to negative predictions is our tendency to believe things that are just plain wrong. We may think we know how the economy works, or why some kids grow up to commit crimes and other don’t, or how human activities affect the global climate, but in most cases, we don’t. Most of what we believe is superficial and often not true on some important, fundamental level.

Ask a well-educated, partisan Republican about the likely effects of lowering federal taxes for the economy-at-large, and you will get a simple, coherent answer: “Lower taxes will grow the economy.” But that opinion is just wrong.

Does lowering taxes increase economic growth? The economic research does not provide pithy answers to that question.

Two economists at the left-leaning Brookings Institute, William G. Gale and Andrew A. Samwick, concluded in their 2014 study that “if the tax cuts are not financed by immediate spending cuts they will likely also result in an increased federal budget deficit, which in the long-term will reduce national saving and raise interest rates.” Even if there is a short-term boost to economic growth from a tax cut, the long-term net result may be small or even negative, according to Gale and Samwick.

Even the conservative-leaning Tax Foundation has concluded that simple statements such as “lower taxes lead to economic growth” do not reflect reality enough to inform budget and tax policies.

The Tax Foundation’s William McBride writes: “The economy is sufficiently complex that virtually any theory can find some support in the data.”

Yet, the Republican Party has achieved 40 years of political dominance partially around the much over-simplified belief that lower taxes lead to more growth.

But its not just the GOP. You can’t go to a Democratic Party rally without someone calling for an increase in the minimum wage, on the belief that such a policy move would increase the economic security of millions of working Americans.

Would it?

The economic research is mixed, at best, at the effectiveness of minimum wage increases at increasing the standard of living for low-skilled labor. Some research suggests raising the minimum wage actually reduces employment opportunities for low-skilled labor. The very people that need these minimum-wage jobs the most may be most harmed by increasing the minimum wage.

Yet, Democratic Party leaders are not held accountable for the empirical weaknesses in their policy proposals. Sure, Fox News and the Republican Party will hold them accountable, but today’s partisan voters are so well-trained to avoid contradictory information that they may never hear substantive counter-arguments to raising the minimum wage. In Walter Cronkite’s 1968, the average voter had a good chance of inadvertently coming into contact with information that might challenge the voter’s view of the world, but not today.

Are we doomed to hyper-partisanship forever?

You know partisanship has gotten out of control when a U.S. Senate candidate, asked whether he dated teenage girls when he was in his 30s, replies, “Not generally, no…” and he only loses the election by one and a half percentage points. Granted, it was Alabama, but still…

But now for the good news…hyper-partisanship is not necessarily a permanent aspect of our modern democracy. We can reduce today’s ideological polarization and the political dysfunction it breeds. And we can do it without over-regulating Facebook or forcing people to watch broadcast television news again.

In a follow-up to this essay, I will share how I re-trained myself to stop passing new information through a partisan or ideological lens and to instead do something few of us are good at any more.

It is called listening. And it turns out to be much harder to do than it sounds.

Part 2 of this essay provides some simple steps to recover from today’s hyper-partisanship epidemic.

K.R.K.

About the author: Kent Kroeger is a writer and statistical consultant with over 30 -years experience measuring and analyzing public opinion for public and private sector clients. He also spent ten years working for the U.S. Department of Defense’s Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness and the Defense Intelligence Agency. He holds a B.S. degree in Journalism/Political Science from The University of Iowa, and an M.A. in Quantitative Methods from Columbia University (New York, NY). He lives in Ewing, New Jersey with his wife and son.