By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, November 8, 2017)

{Feel free to send any comments about this essay to: kkroeger@nuqum.com or kentkroeger3@gmail.com}

Rush Limbaugh tried hard on Wednesday morning to rationalize the Republican defeat in Virginia as something unrelated to President Donald Trump — but, after an hour, his enthusiasm for the project waned.

“I don’t do phony optimism and I don’t try to cheer people up when it isn’t warranted…I’m the mayor of Realville,” said Limbaugh.

For those of you not sure, Realville is not an actual place — which was symbolic of Rush’s plea to his faithful listeners. His rationalization of the Virginia elections was going nowhere.

[Fact Checker’s Note: There is, in fact, a Réalville. But it is in southern France and we verified that Rush Limbaugh is not their mayor.]

There is no positive spin Republicans can assign to the Democrats’ victories in Virginia (and elsewhere). The GOP didn’t just lose in Virginia, they weren’t even competitive. More distressing to them should be the turnover of Virginia’s lower house to the Democrats.

The Democratic Party’s victory on Tuesday was deep in northern Virginia, and may foretell the ‘Thus Always to Tyrants‘ state finally becoming reliably blue for Democrats.

Hillary Clinton won Virginia in 2016 by a 50 percent to 44 percent margin, with 6 percent of the vote going to third party candidates. Ralph Northam beat Ed Gillespie by a 54 percent to 45 percent margin, with only one percent going to Cliff Hyra, the Libertarian candidate.

Without an intensive look at individual-level vote data (such as The Washington Post’s exit poll data), it is difficult to make strong conclusions about the 2017 Virginia elections; however, Tuesday’s election results are consistent with Berniecrats’ claims that a large majority of the third party presidential vote in 2016 would have gone to the Democratic candidate had the nominee been anyone other than Hillary Clinton.

Yet, the shift of 2016 third party voters to Northam in the Virginia gubernatorial race is not the takeaway from Tuesday’s elections. The story was the vulnerability of incumbent Virginia legislature Republicans in what had been strong Republican districts.

Democrats won Virginia districts in places they had no business being competitive.

A 73-year-old Republican incumbent, Bob Marshall, an aggressively anti-LGBTQ state house legislator, lost to Danica Roem, the first openly transgender candidate in U.S. history. Their northern Virginia district is an historically conservative district along Highway 28 with a resident population that is prosperous with strong ties to the Washington, D.C. and federal government economy.

That Virginia state house race saw Roem pursue a clear, but understated, millennial-centered social justice agenda versus a Republican incumbent clinging desperately to a worldview that fit well in 1957, not 2017.

The Republicans should hope that race does not reflect nationwide trends. However, it probably does.

However, let’s step back from the this week’s GOP shellacking and think more strategically about the lessons both parties should have learned from the Virginia results. The early conclusions from mainstream pundits, unsurprisingly, are punctuated with hyperbole and unsupported speculation.

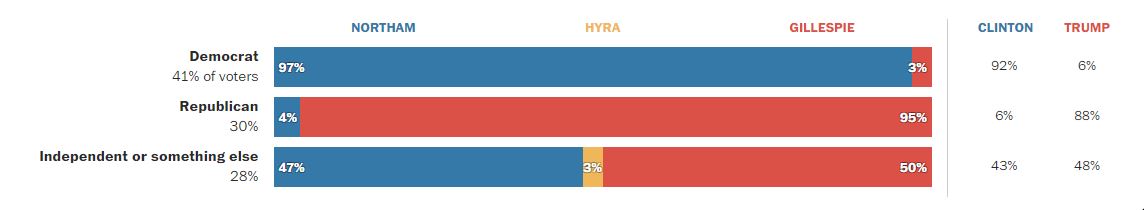

This was a referendum election, not an ideological one. Virginia independents, representing about 28 percent of the voter population, went slightly for Gillespie over Northan (50% to 47%, respectively), according to the Washington Post’s exit poll analysis. Gillespie did slightly better than Trump among independents.

Still, beyond the importance of partisanship and turnout, there are other significant lessons both parties can take away from Tuesdays results.

First, the Republicans:

Lesson 1:

The American political system is venting Republicans like Bob Marshall. Their worldview is not relevant or sustainable in our country’s globalized, intercultural social landscape.

A good share of these Republicans will survive in a smattering of Southern and Midwest states, but the Bob Marshalls are done. Being a bigot isn’t just a bad way to go through life, in politics it produces socially radioactive fallout whose blowback is hard to predict and control. The Republicans don’t need that uncertainty right now. And they definitely don’t need it

The Republicans of the future are going to be more like United Nations ambassador Nikki Haley or U.S. House Representative Cathy McMorris Rodgers (Washington’s 5th congressional district). If the 2017 Virginia results teach the Republicans anything, it is that the GOP old guard needs to retire — which they are…in droves.

To paraphrase Gothmog, lieutenant of Morgul in The Lord of the Rings, “The age of old white men is over, the time of multi-ethnic women has come.”

Nikki Haley, Kamala Harris, Tulsi Gabbard, Tammy Duckworth, Jaime Herrera Beutler…..

To be fair, not all white men need to retire.

Bernie Sanders thrives because he speaks with credibility and passion on the issues and concerns of millennials and young, working-class Americans. The Bob Marshalls (and Chuck Schumers) do not.

Just as many of us prepare for winter by sorting through our firewood supply and throwing out the wet and rotted logs — usually the older logs on the bottom of the pile — that is what the Republicans are doing in preparation for 2018 and 2020.

In this way, the 2017 Virginia state house results did the GOP a favor.

Lesson 2:

The Virginia 2017 election results were a referendum on Donald Trump, not on conservatism.

As far as we can tell from the aggregate voting data on Tuesday, the results were not rooted in an ideological re-alignment of voters, but rather resulted from a partisan turnout differential caused by an unpopular president. In northern Virginia, populated by a high percentage of federal government workers and contractors, the voter turnout was decisively in favor of the Democrats.

The Washington Post’s election analysis describes well the dynamic in Virginia. The vote was highly partisan — very little voting across party lines. In addition, Democrats were far more energized than the Republicans. That is the definition of a ‘referendum’ vote. Democrats are angry and frustrated and they took it out on Virginia Republicans.

There is no indication, as yet, that weak Republican partisans or Republican-leaning independents made a wholesale shift towards the Democrats. If that did happen, then the Republicans would really be in trouble going into 2018 and 2020.

For now, they have a much more tractable enthusiasm problem.

Lesson 3:

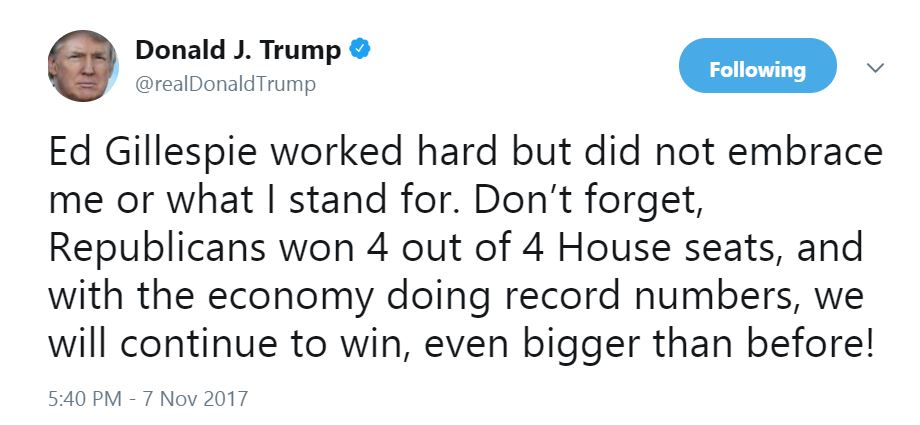

Donald Trump doesn’t really care about Republicans or conservatism, or anything requiring significant amounts of intellectual investment. It took him about 10 minutes to throw his own party under the bus after learning about the Virginia results.

That was a predictable prick move on the part of President Trump. We’ve come to expect this from him. [Is anyone in a near-orbit to Trump telling him that the strong economy is not translating into support for his presidency?]

Electoral success at all levels of government requires a coherent and coordinated team effort and it hurts a party on the down-ballot races when their own president shows no propensity for teamwork. [Obama and the Clintons weren’t much better in this regard — ‘cult of personality’ candidacies never end well for the respective party]

He still inspires a significant percentage of disgruntled Americans — perhaps as high as 40 percent and as low as 30 percent of Americans. He does not, however, appear capable of inspiring another 10 to 15 percent of Americans required to form a durable electoral majority at all levels of government.

That is a problem Republicans need to address ASAP.

Now, for the Democrats:

Lesson 1:

There is no evidence Tuesday’s results were ideological. It was a referendum on Donald Trump. This is hardly news, but its strategic ramifications are still too often over-looked.

The vote outcomes in Virginia, New Jersey, Georgia and Washington state were turnout-driven partisan body counts. Democrats (and Democrat-leaning independents) came out to vote and they voted for the Democrats. In contrast, the now infamous Trump working-class Democrats did not show up in high numbers. Republican incumbents, never previously considered vulnerable, went down all over Virginia and Georgia.

The ‘not Donald Trump’ message will probably work just as well in 2018 (though one year is a long time in politics). The past failures of the Democrats’ mobilization-centric strategy — where money and time is spent on getting partisans to the polls and little spent on voter persuasion — will most likely work well in 2018.

But, the Democrats cannot pretend that the 2017 results are more than this simple fact: a large majority of Americans in shock about the behavior of their current president and are going to take it out on the party that enables him.

The Virginia vote does not portend a larger movement in support of the national Democratic platform. Danica Roem talked more about road building and infrastructure than social justice issues.

Had we seen traditional Republican voters turning out to vote for Democrats, then an ideological shift could be conjectured. As far as we know now, that did not happen.

Lesson 2:

Democrats can be competitive in districts presently viewed as ‘safe Republican’ districts. If the conditions behind the 2017 results hold, the Republicans will lose the U.S. House and it won’t even be close. It could be on a scale similar to the meltdown the Democrats experienced in the 2010 midterms.

A good example of this new competitiveness is found in Virginia’s 10th House of Delegates district, which covers much of the U.S. Highway 50 corridor west of metropolitan Washington, D.C. The Republican incumbent Randall Minchew received more votes in the 2017 election (14,014) than in any previous election, and still lost to Wendy Gooditis by over 1,000 votes.

That is what a partisan edge in voter turnout will do for the Democrats. But the important lesson to Democrats is that they should never be slaves to data analytics and simply ignore districts the “models” deem unwinnable. The models have been wrong in many important races, and they will be wrong again.

Lesson 3:

The Democrats need to hedge their bets and move to the political center.

The enthusiasm may not always be on the side of the Democrats. To assume so, and thereby continue their mobilization-focused strategy in 2018 and beyond, risks the momentum the Democrats currently possess.

It is not a crime against the political gods to hedge one’s bets going into the 2018 midterms. As underwater as Donald Trump’s approval numbers are right now, nobody knows where his approval numbers will be in November 2018.

One substantial international confrontation could overnight put him over 50 percent. And it won’t require a 35-point approval jump George W. Bush saw after 9-11. President Kennedy saw his highest popularity ratings just AFTER the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in 1961. President Ford’s approval ratings jumped sharply after the May, 1975, rescue of the Mayaguez ship crew — where 41 U.S. troops were killed! It is hard to predict how Americans will react to the next international crisis, but don’t assume Democrats and independents, especially those with family members in the military, won’t rally around the Trump presidency during a crisis.

More likely, the American economy will remain strong and at some point that will pay real dividends to the Trump presidency. It hasn’t happened yet, but many Americans still attribute the current economic strength to the Obama administration. That will change as time passes.

In that event, the Democrats need to reacquaint themselves with the political center.

But didn’t I read recently that there is no political center in the U.S. anymore? We are a ‘Center-Left’ country after all.

Many political analysts are saying the growing partisan divide in this country has left the political center empty. Go here and here for recent examples. And many Democratic-leaning pundits have argued the U.S. is a fundamentally Center-Left country (here and here).

All of these conclusions have serious analytic problems.

They are over-reliant on survey-based data, confuse statistical artifacts as findings, misinterpret existing research, and are just blind to the countervailing evidence. Even using the same data and research the ‘go left’ advocates cite, not only is the political center obvious, it is large and still determines close elections in the U.S.

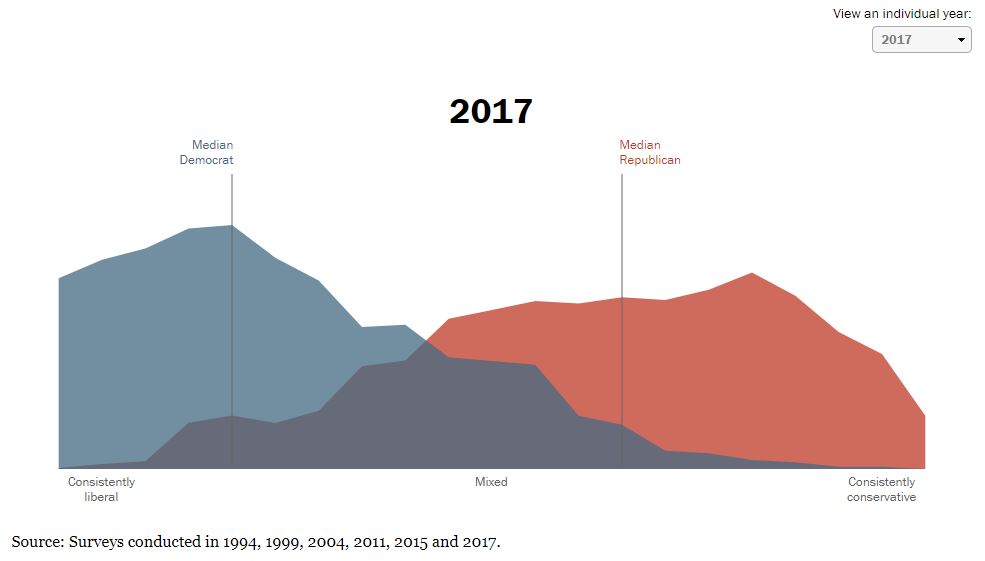

Pew Research’s portrayal of the ideological structure of the American voting public shows a significant political center.

Yes, America is more politically polarized than ever. That does not, in itself, negate the political value of moving to the center. As you can see in the above chart, half of American voters are still between the mean ideological positions of the two parties, but that doesn’t alone justify moving to the center. For example, research is consistently finding that even moderate voters prefer candidates that take distinct policy positions. In corporate marketing, they call it brand differentiation. But taking a distinct policy position is not the same as taking a strong ideological position.

It is possible to be a distinct politician without being a highly ideological.

Here are the three realities that should drive Democrats (and Republicans too) to consider the need for a move to the center:

- When looking at Americans’ opinions on a wide range of topics, particularly outside of a political context, they are predominately non-ideological.

- Americans have a very unfavorable view of both parties (and it is not because they want the parties to become more extreme!)

- Objective policy results still matter in American politics — believe it or not.

Americans are politically ‘Center-Right,’ even if they may be socially ‘Center-Left’

Democratic pundits suggesting we are a ‘Center-Left’ nation put too much weight on survey data alone. Yes, public opinion surveys provide insight into voters’ minds. But these measurement instruments are mirrors, not crystal balls. Change the survey context or the questions themselves and you can get dramatically different results.

Furthermore, the term ‘Center-Left’ is relative. ‘Center-Left’ to what? And is it possible that Americans could be socially liberal, but not politically liberal (Author’s note: That has been my position on this topic in the past).

There are many analytic comparisons a researcher can employ to make this judgment:

- Compare Americans within one election or period of time (cross-sectional)

- Compare Americans over time (longitudinal)

- Compare Americans to other countries (cross-national)

- Compare actual policy outcomes to ideological divisions (Outcome approach)

- Compare Americans using a relativist measure of ideology (Relativist approach)

- Compare Americans to an objective measure of ideology (Objectivist approach)

I won’t go through all these approaches, but would like to highlight the last one.

The Voter Study Group’s lead analyst, Dr. Lee Drutman, takes the objectivist approach in which the center position in a survey question represents the dividing line between ‘liberals’ and ‘conservatives.’ The researcher determines objectively what defines a ‘liberal’ from a ‘conservative’ and looks to see how the American public matches up to the researcher’s definitions.

There is a significant danger of bias in such an approach. It is prone — scratch that — it invites the results to conform to the researcher’s view of the political world. It fulfills what conservative pundit Ben Shapiro describes as the left’s pathological need to believe most Americans agree with them. This approach imposes a cognitive structure on respondents that doesn’t necessarily mirror how respondents actually think.

Furthermore, the objectivist approach ignores the ability of political parties to strategically redefine ideology within the dynamics of electoral politics.

The objectivist approach becomes obsolete as soon as one party redefines what it means to be ‘conservative’ or ‘liberal.’

Oh, when has that ever happened?!

Most recently, the dramatic ideological shift on trade policy is one example of when assumptions on what is the ‘left’ versus ‘right’ position has proven to be fluid relative to time and space.

But the most dramatic example is the Republican Party in the mid-1970s.

The Republican Party in the mid-1970s was a smoldering wreckage following Watergate and the Vietnam War. The dominant question within the Republican Party in 1975 was “what do we stand for?”

“Moderate” Republicans such as President Gerald Ford and Nelson Rockefeller were not popular with the Republican base.

Enter Ronald Reagan who redefined ‘American conservatism’ in a way that persists to this day.

And, subsequently, in reaction to the Reagan revolution, Bill Clinton redefined liberalism, not just to re-center the Democrats on economic policy (which he did), but to define a new form of ‘liberal’ that embraced free markets and the progressive Democratic social agendas (minus LGBTQ issues that would need to wait until the Obama administration to see significant positive action).

Ideological plasticity is where strategic-thinking parties and politicians excel in order to win elections.

So, Democrats, there will always be a ‘conservative’ America out there, regardless of how you define ‘conservative.’ And, over time, they will win half of all elections.

Using the opinion survey method to map ideology includes other qualifiers. If you ask the right set of questions framed in a specific context, Americans can look as leftist (or rightist) as you want them to look. That doesn’t mean the objectivist approach is fruitless, but it does mean a skeptical person should look for additional information before concluding we are a ‘Center-Left’ nation.

So here is a brief look at another ideological data source…

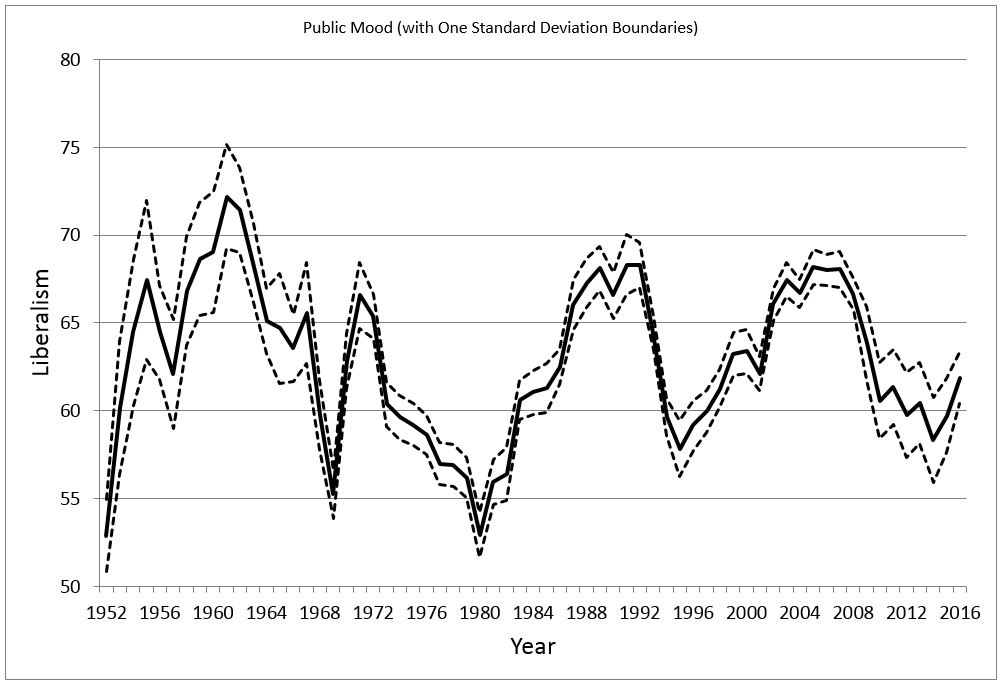

University of North Carolina political scientist James Stimson has been tracking the political mood of Americans for most of his academic career. Unlike Pew Research or the Voter Study Group, Stimson’s measure of public mood (which is analogous to ideology) looks out over 60 years of survey data using multiple survey vendors and questions (an in depth methodology description of Stimson’s public mood measure can be found here). Pew Research and The Polling Company (the survey vendor for The Voter Study Group) do good survey research. But I prefer a survey-based opinion measure that aggregates multiple survey vendors and questions over time and looks at more than just voters, but the entire U.S. adult population.

Stimson’s most recent update on public mood shows America (as of 2016) is still centrist, compared to other times in American history since 1952.

The mean value in public mood is 63, almost exactly where American public mood stood in 2016. As I’ve said, it is very likely this country has become significantly more liberal since the 2016 elections. That is the common ideological reaction to a new president. Notice that prior to 1980, America’s mood was the most conservative it had ever been since 1952. Hence, Ronald Reagan wins in landslide over Jimmy Carter. Immediately after the 1980 election, we witness the American mood becoming more liberal.

[Author’s note: Many of us still remember how the American mainstream media outlets ‘freaked out’ at Reagan’s victory in 1980, in much the same way they are reacting to President Trump today.]

In 2016, heading into the November elections, Americans were about as liberal as they were in 1984, right before Ronald Reagan won the biggest presidential landslide since FDR in 1936.

However, the real power of Stimson’s public mood measure is its visualization of the significant year-to-year elasticity in public mood. Real changes in public mood materialize in relatively short periods of time. This is why we shouldn’t be too surprised when opinion data in 2017 is more ‘liberal’ than it was prior to the 2016 elections. It also means analysts, researchers, and pundits should confess more humility before making declarations about how this country is ‘Center-Left’ or ‘Center-Right.’ [Author’s note: I would benefit from some of that humility too.]

To declare that Americans are more liberal today than on November 7, 2016, that’s fine. It doesn’t change the fact that we were a centrist country going into that election and any ideological moves since then can be quickly reversed or accelerated.

Maybe the real conclusion should be that declaring the the U.S. as “Center-Left” or “Center-Right” is analytically unproductive. Any such judgment is as permanent as a child’s sand castle. Perhaps the real effort from analysts and party strategists should instead be focused on the forces that build (and destroy) those ideological castles.

Yes, there is a political center and it deserves our attention

There need not be a large number of voters at the political center for the strategy of moving to the center to be effective. Voter behavior is not as spatially-driven or as simplistic as often assumed by the “go left” Democrat crowd. Gabriel Lenz’ research shows that many voters move their attitudes towards their preferred party and candidates’ positions, not the other way around. So parties or politicians aiming for the thick part of the ideological distribution are not necessarily the most successful. Thus, the ideological distribution of Americans today is not, ipso facto, an argument for where the party should go in the future.

Here is the actual secret sauce to durable and sustainable electoral success in the U.S. political system….

…enact good public policies (which, sometimes, means ‘do nothing’) and voters will reward the party and politicians in power. Good policies attract voters.

Is that why incumbents win over 90 percent of the time?

No, not entirely. But it would be inaccurate to suggest this country has made a lot of bad public policy decisions. This country is as strong economically as it as ever been. For the most part, our political leaders make good policy and are thus rewarded for this.

Are you out of your f**king mind?! Have you heard of G. W. Bush’s Iraq War? The Defense of Marriage Act? The Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act of 1988?

Yes, there are really bad U.S. public policy decisions in the history books. In most cases, the incumbent party was punished for them.

We can’t allow an aggregate statistic such as incumbent re-election rates to blind us to the real political changes that occur during bad economic times or counter-productive military adventures.

Americans reward good policy and punish bad policy.

And knowing that should shape how the Democrats move forward.

If Democratic leaders believe raising the minimum wage to $15-an-hour, or providing free tuition to public universities for qualified students, or raising taxes on high-income households, or imposing a carbon tax on energy users and producers, or creating a single-payer health care system, or creating government-funded child care are good public policies, then, absolutely, the Democrats need to move left.

If you are skeptical that these policies can be implemented in a cost-effective manner (or would even work if implemented) and that there is a limit to the long-term debt our economy can carry, then, as a Democrat, you must pump the party’s brakes on these leftist economic policy ideas.

That leaves the social justice issues as the only other area where the Democrats can move left. But here is the problem with that move….the Democrats are already on the extreme left on many of these issues. There is no place farther left position than your last presidential nominee’s position of ‘unrestricted access to abortion.’ Allowing people to choose their bathroom based on their self-determined gender identity, independent of their birth sex assignment, is ex vi termini the ‘extreme left’ position. Where is there left, pardon the pun, for the Democrats to go?

The ‘go left’ Democrats are still fighting the war against Hillary Clinton — a unapologetic centrist that put corporate interests ahead of all other considerations. But, Hillary’s problem wasn’t her squishy centrist positions. The problem was her. She was too unlikable to overcome her bland ideas. As we saw in Virginia when the Democratic base in energized, the Democrats win. In 2016, the Democratic base was’t energized, but it wasn’t because of Hillary’s tendency for centrism.

Had Hillary Clinton been even a little more honest, a little more transparent, a little more charismatic, and not deny attention to working-class America, I wouldn’t have been forced to wake up to this picture today:

K.R.K

About the author: Kent Kroeger is a writer and statistical consultant with over 30 -years experience measuring and analyzing public opinion for public and private sector clients. He also spent ten years working for the U.S. Department of Defense’s Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness and the Defense Intelligence Agency. He holds a B.S. degree in Journalism/Political Science from The University of Iowa, and an M.A. in Quantitative Methods from Columbia University (New York, NY). He lives in Ewing, New Jersey with his wife and son.