By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, March 28, 2018)

{Send comments to: kkroeger@nuqum.com}

“It’s discouraging to think how many people are shocked by honesty and how few by deceit.”

― Noël Coward

In the 2016 election, many people thought President Donald Trump was honest, or was, at least, selectively honest.

“He says it like it is — he doesn’t speak out of both sides of his mouth like other politicians,” a Trump supporter told me as he waited for Trump to arrive at a Des Moines, Iowa campaign rally early in the 2016 presidential campaign.

What he was describing was more Trump’s off-the-cuff, rambling speaking style, not his honesty. Nonetheless, relative to other politicians, Trump was a refreshing change of pace to many voters.

Voters know politicians lie. They even understand why on some level. We all lie over the course of a lifetime for various reasons: to protect someone’s feelings, to motivate people, to avoid a conflict the truth would otherwise ignite, or to hide our own mistakes, misdeeds, or inadequacies.

It is human to lie.

“To keep society running smoothly, we need to tell white lies,” says Dr. Paul Seager, a Senior Lecturer at the University of Central Lancashire (UK). “We all lie and those who say they don’t are probably the biggest liars of all.”

But not everyone that studies deception and lying agrees with Seager’s conclusion that it benefits society or that all people are predestined to be liars.

“We are not born liars,” says Dr. Roland Losif Moraru, a psychologist from the University of Petrosani (Romania). “There are lots of reasons that could motivate people to tell lies, and even though each reason might be different than the other, all of them stem from one root cause which is being unable to bear the consequences of telling the truth.”

“Lack of courage, lack of problem-solving skills and lack of the ability to properly handle unexpected events may make escaping from a situation a much better option than facing it,” says M. Farouk Radwan, author of How to Make Someone Fall in Love with You. “Consequently, lying is the combination of being unable to face the results of honesty and the lack of proper values.”

That last sentence may be a perfect summary of America’s political class.

Donald Trump was elected, in part, due to his blunt, unfiltered, and generally unstructured way of speaking. In the view of his supporters, his frankness is one of his defining qualities. To his detractors, at best, he is an “intellectual sloth” prone to falsehoods, if for no other reason than, he doesn’t know the truth in many cases. At worst, he is a scheming charlatan dedicated to abusing the power of the presidency for his own private gain (perhaps to also serve the interests of his Russian handlers).

Conservative columnist George Will pointedly said of Trump’s chronic estrangement from knowledge, “The problem isn’t that he does not know this or that, or that he does not know that he does not know this or that. Rather, the dangerous thing is that he does not know what it is to know something.”

“This seems to be not a mere disinclination but a disability. It is not merely the result of intellectual sloth but of an untrained mind bereft of information and married to stratospheric self-confidence,” Will wrote.

But speaking in ignorance, as Trump often does, is a different form of lying. To assert a point of fact while not knowing if it is true seems particularly noxious. It may not fit into a narrow definition of lying, but its consequences can be every bit as consequential.

U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell asserting at a 2003 UN Security Council meeting that Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi regime had an active weapons of mass destruction (WMD) program an example of a political lie? Or was it just wishful thinking given the decision to go to war with Iraq had all but been made?

Former members of the George W. Bush administration continue to argue their mistake on Iraqi WMDs was either an honest one or not a mistake at all.

Secretary Powell, representing the most common defense of the Bush administration’s using Iraqi WMDs as a pretext for war, now calls his UN speech the product of a “great intelligence failure.”

But was it something, in fact, more dishonest than simply a breakdown in the intelligence collection and analysis process?

If Secretary Powell knew it might not be true, was the WMD assertion just another potent type of political lie?

The more conventional definition of lie — when someone with a knowledge of the facts consciously misrepresents those facts to further an agenda — may generally be considered the clearest form of lying, but politicians have mastered other methods of manipulating facts to achieve the same goals.

Not all lies are equal

The political dysfunction we experience today is complemented by the inability (or disinterest) of the news media to distinguish between the various types of lies emanating from politicians.

Donald Trump saying he is the “smartest person in a room” is not the same as Barack Obama saying, “If you like the health care plan you have, you can keep it.” Both were lies, but one far more substantive than the other.

The news media tend to deposit all political lies into a collective bucket, regardless of degree or impact, which doesn’t serve the public interest well.

Furthermore, fact-checking websites like Politifact.com tend to focus exclusively on politicians’ statements easily verified through widely-available information sources. But what about situations where the critical knowledge can only be obtained through sources far outside the typical access channels of journalists or the public? Or even members of Congress?

When U.S. Special Operations soldiers died in Niger last year, South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham admitted to NBC’s Chuck Todd on Meet the Press, “I didn’t know there was 1,000 troops in Niger.”

The U.S. Special Forces Niger operation was not a secret. U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) had been openly posting on Twitter about U.S. involvement in Niger since it started in 2013, reports SpecialOperations.com.

If Congress can be in the dark on routine U.S. military operations, it should surprise few people that journalists might also be in the dark. Moreover, the potential for public officials to lie to the news media increases considerably when the government’s activities are off everyone’s radar.

The news media is also ill-equipped to separate truth from fiction when they must assess a politician’s intent.

We may never know Hillary Clinton’s true intent for why she preferred a private server for her work e-mails over the more legally-appropriate (and probably more secure) e-mail system already in place at the U.S State Department.

But her intent is the essence of whether or not she lied when she told reporters she chose the home-brew system for its “convenience.” Her explanation reminded me of George Washington’s famous line: “It is better to offer no excuse than a bad one.”

By shielding her emails from public scrutiny, including the deletion of over 30,000 emails after the emails had been subpoenaed by a congressional committee, it became reasonable to ask, “What is she hiding?”

There is a substantive difference between Donald Trump sending out his press secretary Sean Spicer to lie about the size of the crowd at the presidential inaugural and Hillary Clinton’s mendacity regarding why she needed a private email server.

There was a national security interest in knowing the content of Clinton’s e-mails which resided on a unsecured private network. There was nothing at stake with Spicer’s inaccurate boast about crowd size, except his credibility as a press secretary.

Yet, Politifact.com gave Sean Spicer’s untruth a ‘Pants on Fire‘ rating, while the truthfulness of Clinton’s claim she authorized a private e-mail server for the ‘convenience’ could not be assessed.

Not all lies are equal and treating them as such serves the interests of those telling the most dangerous lies.

If, on the other hand, journalists and the political class were to share a common schema for categorizing the various types of lies one hears in the nation’s capitol, it might aid the public in distinguishing between a ‘run-of-the-mill’ Washington, D.C. lie and one of real consequence.

A Taxonomy of Political Lies

During the 2016 presidential, WNYC’s On the Media radio broadcast, hosted by Bob Garfield and Brooke Gladstone, created their own taxonomy of the classic political lies, which included: lies of omission, lies of distortion, lies of exaggeration, the bald-faced lie, and lies that feel like they must be true.

All excellent types of lies, but for the purpose outlined in this essay, they fail to distinguish the most toxic lies from innocuous ones. Some bald-face political lies are relatively harmless (Donald Trump: “No administration has accomplished more in the first 90 days.”), while others can lead a country into war (George W. Bush: “Intelligence gathered by this and other governments leaves no doubt that the Iraq regime continues to possess and conceal some of the most lethal weapons ever devised.”).

Instead, a useful taxonomy of political lies needs to go beyond simply the content of the lie (exaggeration, distortion, factual omissions) and attempt to discern its scope and purpose.

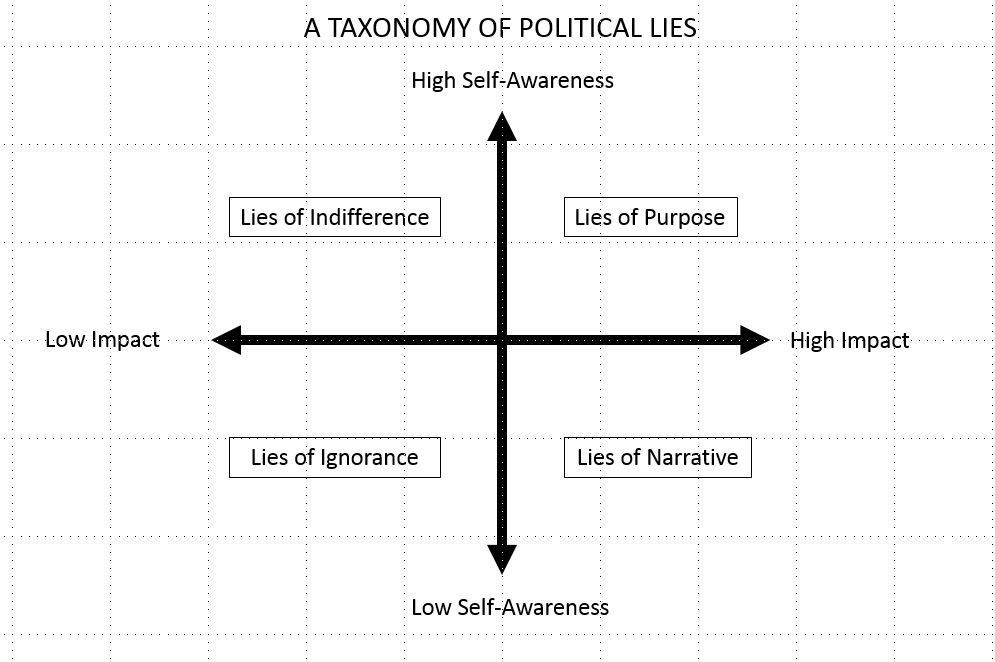

In that effort, here is a simple taxonomy of political lies that distinguishes them along two dimensions:

- Self-awareness — is there good reason to believe the (alleged) liar knows if they are telling a lie?

- Impact — does the (alleged) lie relate to a subject matter of great importance or impact (e.g., national security, a major federal policy, etc.)?

In many cases, where a lie fits on both dimensions will be a subjective judgment and won’t be known with any certainty, if ever, until many years have passed. In other cases, it may be easier to determine the substance of a lie than the self-awareness of the liar. A liar’s intent is particularly difficult to discern as it often requires knowing what was in their heart at the time they spoke an untruth.

Clinton saying “the private e-mail server was for convenience” is impossible to prove as lie unless she left a documented record of saying otherwise. And she didn’t, as far as we know.

Still, the taxonomy of political lies can help journalists and the public decide what politician-sourced untruths are more important than others, even when it is unclear if an untruth has been spoken.

Figure 1 below shows the basic dimensions of the political lie taxonomy. The horizontal axis assesses the potential impact of the lie based on its subject matter. For example, a lie about the outcome of a military engagement is less consequential than a lie about campaign donations. The vertical axis is based on the degree to which the (alleged) liar is aware they are telling a lie. As mentioned, it is usually difficult to know the extent to which the liar is aware they are telling a lie. A better way to utilize the ‘self-awareness’ dimension therefore is to estimate the probability that the (alleged) liar is consciously lying. For example, we can say with high probability now that Richard Nixon knew about his White House’s effort to cover up the Watergate break-in. It always helps, of course, when there is a documented admission as there was in Nixon’s case. In contrast, there is decent probability that Donald Trump believes he had the largest inauguration audience in history.

The two-dimension taxonomy creates four categories of lies. There are lies of ignorance, lies of indifference, lies of narrative, and lies of purpose. Generally, the most serious lies will be those with a potentially high impact (Lies of Purpose and Lies of Narrative).

Figure 2 provides a short description of the four lie types and Figure 3 offers examples from history of each lie type.

We will start in the lower left-hand quadrant: Lies of Ignorance. This is probably the easiest category to explain and some will rightfully argue this is not really a lie. This is the type of lie where we often speak using gross simplifications, or go “outside the data,” or talk in areas far outside our areas of competency. Such a lie can be driven by a desire just to be social or out of our need to be respected for our intelligence. Insecure people often tell these types of lies and might account for the vast of majority of Trump’s spoken untruths.

There is one caveat with this category, however. Being wrong about a point of fact is not the same as lying. For a politician’s untruthfulness to earn a spot in this quadrant, they must recklessly disregard any attempt to learn the facts before they speak their untruth. I stand guilty of this lie more times than I’d like to admit but it is Trump that has taken this category to weapons-grade levels.

The second quadrant — Lies of Indifference — is populated by political lies where the speaker of the lie knows they are lying but it concerns a matter of relative lesser importance. A recent example would be former press secretary Sean Spicer telling the press corps that Trump’s inauguration was the most watched ever. It wasn’t, even if you include online and replay viewers.

Some could this is the worst kind of lie, since you knowingly do it even though it concerns something of relative insignificance. Only a congenital liar would potentially compromise their integrity and trustworthiness for a lie whose benefits would be minimal at best. Trump telling Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau that the U.S. has a trade deficit with Canada (which is not true and Trudeau immediately challenged Trump on the claim) was a pointless effort and served no tangible purpose.

The third quadrant — Lies of Narrative — includes lies that are often controversial in that the liar contends they ‘honestly believed’ the untruth they told. Short of a deathbed confession stating otherwise, these lies are taken on faith that the liar is telling their truth about their ignorance. What makes this problematic is that lies of narrative concern issues of high importance (national security, federal legislation, etc.). I am convinced that when Trump said of illegal Mexican immigrants — “They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people” — he was certain of his statement’s truth. That shouldn’t exonerate him for the depth of the lie.

Lies of narrative, as the label implies, typically propel a larger narrative in the political blood stream. A better example may be Powell’s WND speech before the UN. On his word, I accept that he believed the intelligence given to him. But Powell is a bright man. He knew the score when he was provided the intelligence on the non-existent Iraqi WND program. The U.S. was going to war with Iraq. The narrative was set. Powell just needed to advance the ball one more step. These lies may be the most dangerous as politicians have mastered them as tools to avoid the consequences of their infidelity to the truth. If caught speaking untruths, they just need claim they acted in good faith. As long as they don’t document their deliberate misapplication of the facts, who can prove otherwise? Forthright ignorance is a viable defense in Washington, D.C.

The fourth quadrant — Lies of Purpose — includes lies that we probably think of when we think of political lies. Watergate. Tammany Hall. Gulf of Tonkin. Iran-Contra Affair. This category also includes less criminal but still significant lies such as President Obama’s claim about the Affordable Healthcare Act (ACA) that “if you like the health care plan you have, you can keep it.”

Their defining characteristic is that the (alleged) liar knew they were speaking an untruth but did so in the pursuit of a specific political outcome or personal gain. It was pre-meditated. They didn’t just turn a blind-eye to contradictory evidence. They actively strangled and buried it.

When is a lie better than the truth?

Leo Tolstoy has an answer for this last question: “Anything is better than lies and deceit.”

Yet, today, the observation that lying is an art from in Washington, D.C. is hopelessly banal. Career politicians and senior civil servants cannot survive long without mastering this dark art.

Lying is a survival tool and the successful politicians know how to wield its powers. In contrast, Jimmy Carter’s failures as president were exacerbated by his unwillingness to employ it on the political battlefield.

“Jimmy Carter may have been wrong — often — but one thing he was not was a liar,” says conservative blogger David Pettit. “He was and is a great human being who was wholly unsuited for the deceptive and underhanded rigors of the Office of President.”

In contrast, there is Bill Clinton. A man that many regard as a successful, though under-achieving, president. Perhaps more than any president in history, lies for him were purely utilitarian devices. He used lies the way you use shortcut keys on your laptop keyboard. His lies helped him to survive to fight another day. The ends justified the means, and if it required lies to achieve a larger goal, so be it.

The lesson to be learned from the 2016 election is that simple definitions of lying don’t convey their power or their impact on voters. Millions of Americans did not care that Trump didn’t tell the truth a lot of the time. When it mattered to them, they thought he was a truth-teller. Even if the facts proved otherwise.

At the end of the 2016 presidential campaign the Washington Post determined that 64 percent of all Trump statements were totally false. Compare that to the average politician who makes completely false statements 10 to 20 percent of the time.

The wrong conclusion from 2016 and the Trump presidency is not that we are in a post-truth era. Speaking the truth has been and will always be important, particularly from our elected leaders. What has happened, however, is that the use of lies has become so ingrained in our political culture, we don’t see it anymore. Its like that ugly, textured wallpaper your mom put up in the kitchen in the mid-70s. After awhile, you don’t see it anymore, but it is no less ugly.

We don’t need the ‘deep state’ concept to recognize that it is too acceptable for the political establishment to say one thing among themselves, but something totally different when they speak to the public. In fact, the media and political elites lionized President Bill Clinton for his ability to prevaricate for political purposes, even as they feigned in public how disgusted they were at how effortless it was for him to do so.

His wife, Hillary Clinton, probably said it best in her April 2013 speech to Wall Street banking executives: “If everybody’s watching all of the backroom discussions and the deals, then people get a little nervous, to say the least. So you need both a public and a private position. You just have to sort of figure out how to balance the public and the private efforts that are necessary to be successful, politically, and that’s not just a comment about today.”

In Topeka, Kansas, that is called lying. In the social circles of our political and media elites, that’s called being smart.

Perhaps these words from author Laura Ingalls Wilder, who, not coincidentally, was raised in the Midwest, can help bring a culture of honesty back to our political system:

“The real things haven’t changed. It is still best to be honest and truthful; to make the most of what we have; to be happy with simple pleasures; and have courage when things go wrong.”

― Laura Ingalls Wilder

K.R.K.

{Send comments to: kkroeger@nuqum.com}

About the author: Kent Kroeger is a writer and statistical consultant with over 30 -years experience measuring and analyzing public opinion for public and private sector clients. He also spent ten years working for the U.S. Department of Defense’s Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness and the Defense Intelligence Agency. He holds a B.S. degree in Journalism/Political Science from The University of Iowa, and an M.A. in Quantitative Methods from Columbia University (New York, NY). He lives in Ewing, New Jersey with his wife and son.