Diagram above shows the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths in Israel as of September 8, 2020. (Image by Hbf878)

By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; September 14, 2020)

If one were to pick a country best equipped to deal with the challenges of the coronavirus, one’s first choice might have been Israel.

This is a small-population country (8.9 million) that knows how to control the movement of people and commerce across and within its borders. In 2011, according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), Israel had approximately 500 roadblocks and checkpoints in the West Bank alone, not including the almost 500 “flying” (or “random”) roadblocks that exist at any given moment in time.

Israel also has a world-class, universal health care system–ranked 4th among 48 nations, according to a 2013 Bloomberg study in which the U.S. ranked near the bottom. Only Hong Kong, Singapore and Japan ranked higher than Israel.

On a indirect level, Israel ranks high among the advanced economies for its science and technological innovation–a quality that would, presumably, be of value during a pandemic in which the antagonizing pathogen is largely unfamiliar.

Israel should have been an exemplar during this health crisis–and early in the pandemic, the country was just that.

“Israel beat the coronavirus. Or at least that’s what the public were led to believe. Benjamin Netanyahu held a press conference to crow about Israel’s ‘great success story’ and how foreign leaders the world over were calling him for advice on how to battle the pandemic,” writes Middle East-focused journalist Neri Zilber. “Fast forward two months and there are over a thousand new infections per day. On a per capita basis the curve is a sheer straight line hurtling upwards to American and Brazilian levels.”

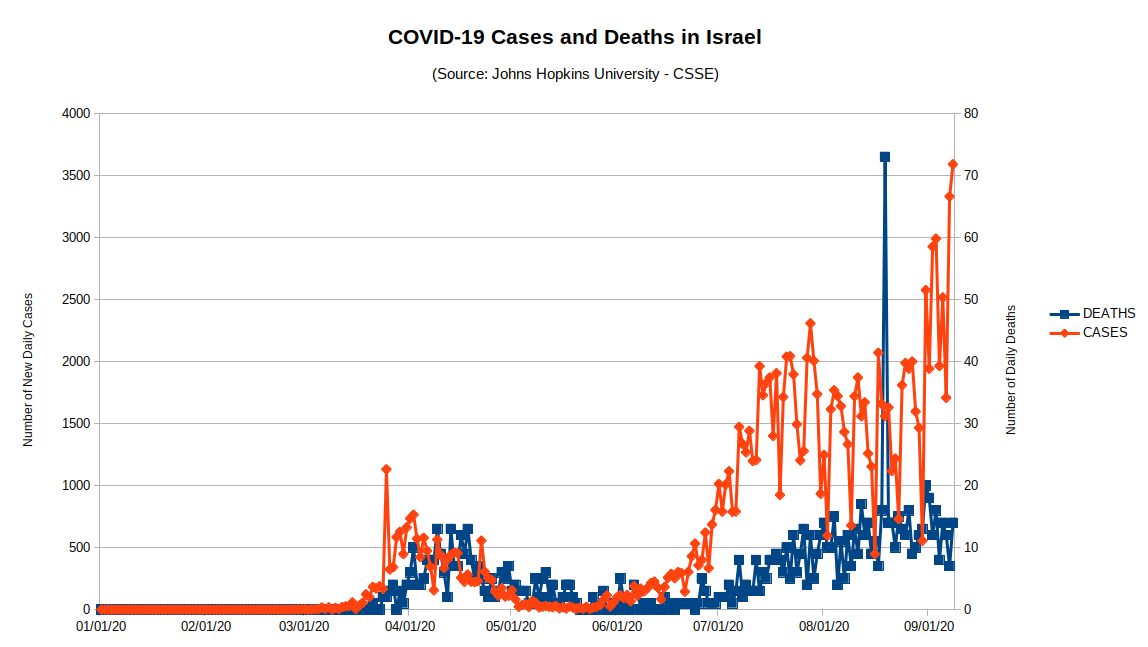

Figure 1 (below) shows the two coronavirus waves that have hit Israel. The first wave started in March and peaked at around 15 deaths-a-day in mid-April, and near the end of May the pandemic appeared to be a thing of the past.

Figure 1: COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in Israel (through 8 Sep 2020)

However, in early-June, Israel’s new case numbers began to rise again and rose precipitously through July. Likewise, by a lag of a week or two, the number of new COVID-19 deaths similarly rose.

What went wrong in Israel?

The answers may offer valuable insights to the rest of the world.

For starters, we are dealing with a virus that doesn’t give a damn about the politicians, media stars and policy analysts trying to leverage the pandemic for professional gain. The coronavirus spreads because it can. Yes, policies matter–but only to a degree.

The epidemiological textbooks argue that suppression and mitigation policies–particularly with highly contagious viruses like SARS-CoV-2 (the coronavirus)–are intended to “flatten the curve” in order to lessen the short-term burden on hospitals until a vaccine is available and/or the population attains “herd immunity” levels.

But as WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom recently said, a vaccine for the coronavirus will not necessarily be a “silver bullet” allowing us to go back to normal.

Should a vaccine be developed by the end of the year, it may not be 100 percent effective. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), since 2009, flu vaccines have been no more than 60 percent effective for any given year.

“It’s dangerous for us to be putting all of our eggs in one basket – that a vaccine will become available and this is going to save the day – and forget to remain focused on what we should be doing this very moment,” says Vaccinologist Jon Andrus, an adjunct professor of global health at George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health.

Other epidemiologists echo Andrus’ sentiment, eager to remind us that widespread testing, case identification and tracing, wearing masks, maintaining hygiene and social distancing cannot be neglected even after a safe and effective vaccine becomes widely available.

In Israel’s case, the coronavirus’ summer resurgence has multiple possible causes. Among the earliest cited was the reopening of schools at the end of May.

One study on the resurgence–conducted by Israel’s Health Ministry–showed educational institutions were the most likely location for spreading the virus, accounting for about 10 percent of documented cases.

But epidemiologists have identified additional possible sources of Israel’s second coronavirus wave, such as:

That last point is particularly contentious as it has led some in Israel to question why the Israel’s Health Ministry loosened restrictions on the number of worshipers allowed in synagogues prior to the Tisha B’Av fast (which occurred on July 29-30). There are indications that religious gatherings associated with the Tisha B’Av fast may have been a significant avenue for the virus’ spread within the ultra-Orthodox community.

Israeli research has persuasively already shown that synagogues were a common place for the coronavirus to spread during the first wave of the pandemic–accounting for nearly a quarter of known cases not brought in from abroad or contracted at home, according to a report published by Israel’s Coronavirus National Information and Knowledge Center.

Did Israel loosen restrictions too soon?

The apparent answer to this question is “Yes.”

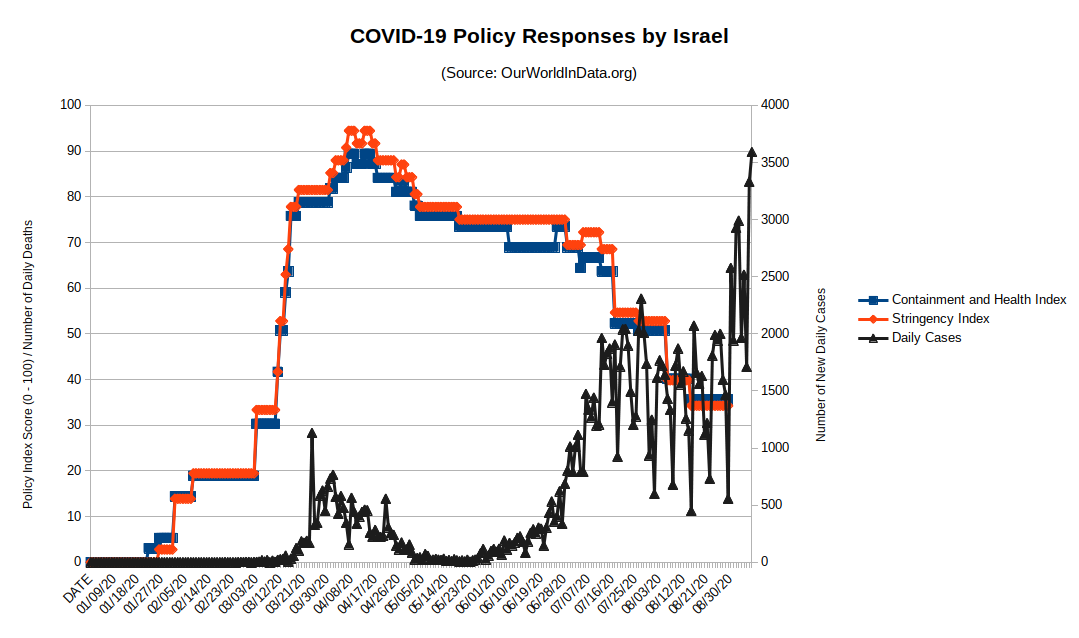

Figure 2 offers visual (though not definitive) evidence that the resurgence of the coronavirus in June and July was preceded by the loosening of coronavirus restrictions, starting in late-April.

Still, we need more systematic evidence showing that changes in public policy have a measurable, meaningful impact on coronavirus outcomes (i.e., cases and deaths).

Using two policy indexes developed by the OxCGRT Project, I analyzed Israel’s policy responses to the coronavirus over time and found a significant, negative relationship between increases in Israeli coronavirus policy measures and decreases in daily coronavirus cases.

For some background, the OxCGRT project calculates a number of policy indexes related to the coronavirus. One index is the Government Stringency Index, a composite measure of nine response metrics: School closures; workplace closures; cancellation of public events; restrictions on public gatherings; closures of public transport; stay-at-home requirements; public information campaigns; restrictions on internal movements; and international travel controls. The index is calculated as the mean score of the nine metrics, each taking a value between 0 and 100. A higher score indicates a stricter government response (i.e. 100 = strictest response). If policies vary at the subnational level, the index is shown as the response level of the strictest sub-region.

The other index of interest is the Containment and Health Index, a composite measure of eleven coronavirus policy response metrics, building on the Government Stringency Index by adding two additional indicators: Testing policy and the extent of contact tracing.

As the two indexes are highly correlated (see Figure 2), for the following analysis I use only the Containment and Health Index.

Additionally, I aggregated the daily coronavirus case data to the weekly level to help reduce data noise. This left me with a time-series data set containing 31 weeks of data.

When comparing daily occurrences of COVID-19 cases in Israel and the country’s policy efforts to control the virus, there was a significant (negative) relationship between those two variables in the fourth, fifth, and sixth weeks after implementation of those policies (see Figure 3). As coronavirus suppression and mitigation policies are increased, new daily coronavirus cases go down. More simply, it takes at least a month before coronavirus containment efforts have a measurable impact on daily changes in new coronavirus cases in Israel.

Figure 3: Cross-correlation between COVID-19 Policy Responses by Israel (Containment and Health Index / Lockdown Stringency Index)

Did Israel relax its coronavirus containment policies too soon?

The answer is a definitive ‘Yes.’

Based on the data, had Israel increased its coronavirus containment efforts at the earliest signs of a second wave increase (i.e, mid-June), the country would probably not be suffering the current increases the country it is now witnessing.

That conclusion is mere conjecture, perhaps, but the dynamics seem rather clear: It takes around a month for coronavirus policies to have an impact and, if true, requires a level of “policy patience” seemingly incompatible with today’s current political environment.

Israel is far from alone in the coronavirus crisis. My hope is that their experience will help inform other countries on how aggressive they need to be to control this virus.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: nuqum@protonmail.com

or DM me on Twitter at: @KRobertKroeger1