_________________________________________________________________________

This is the third essay in a series dedicated to analyzing the U.S. eligible voter population using the 2018 American National Election Study (ANES), an online survey administered in December 2018 by researchers from the University of Michigan and Stanford University.

__________________________________________________________________________

By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; March 14, 2019)

Republican pundits are loving the post-2016 emphasis Democrats place on identity politics, while some Democratic pundits are wringing their hands.

“Embrace of Identity Politics Is Killing Democratic Party”

“Democrats Need to Drop Identity Politics — Now”

“Identity Politics, and the Divisible Nation for Which It Stands”

“Democratic Playbook’s Only Page: Division”

It is a term we cannot escape. But what does it actually mean? And what can the 2018 ANES offer in understanding its importance in today’s political environment.

While I want to keep the pretensions here light, a short discussion of definitions might be helpful.

Stanford philosophy professor Laura Maguire defines identity politics as “when people of a particular race, ethnicity, gender, or religion form alliances and organize politically to defend their group’s interests.” The best known examples would be the feminist, civil rights, and gay rights movements.

But that is a rather narrow, sectarian definition, as people can be engaged in identity politics outside their own identity group. You don’t need to be a woman to be a feminist. And there was a White Panther Party aligned with the Black Panther’s in the late-1960s. Our personal identities don’t limit our potential for engaging across the multidimensional space of identity politics.

Furthermore, identity politics is not as utilitarian as Maguire’s definition. Identity politics can be a private and passive activity as well. A person opposed to — or even ambivalent towards — the interests of other identity groups is participating in identity politics. Of a more consequential nature, making vote choices based on group identities is identity politics. That is a consequential act that requires no more than a private thought and a valid voter registration.

This broadly defined, everyone engages in identity politics, consciously and unconsciously. And with this expansive view of identity politics, I undertook the task of clustering Americans according to how they engage in identity politics.

The Data

The 2018 ANES asked 2,500 respondents a series of attitudinal measures regarding their affinity towards specific identity groups, individuals, social movements, and organizations (see Figure 1). These questions were inputs into a K-means clustering algorithm implemented in the SPSS statistical package.

Figure 1: 2018 ANES Questions Used for Identity Politics Clustering

The K-means clustering algorithm partitions respondents into clusters in which each respondent belongs to the cluster with the nearest mean. To the best extent possible, the aim is to make the clusters as homogeneous as possible while maximizing the differences across clusters.

The most enjoyable task in conducting a cluster analysis is naming the clusters. Ideally, the names are indicative of the “prototypical” member in that cluster. However, in most cluster analyses, particularly those representing large populations, individual clusters can be heterogeneous and the naming process becomes more art than science. That is when it really gets fun.

The Results

With that caveat, I identified five identity politics clusters (IPCs) in the U.S. eligible voter population. Within each of these IPCs, additional sub-clusters were identified and will be discussed in a future essay.

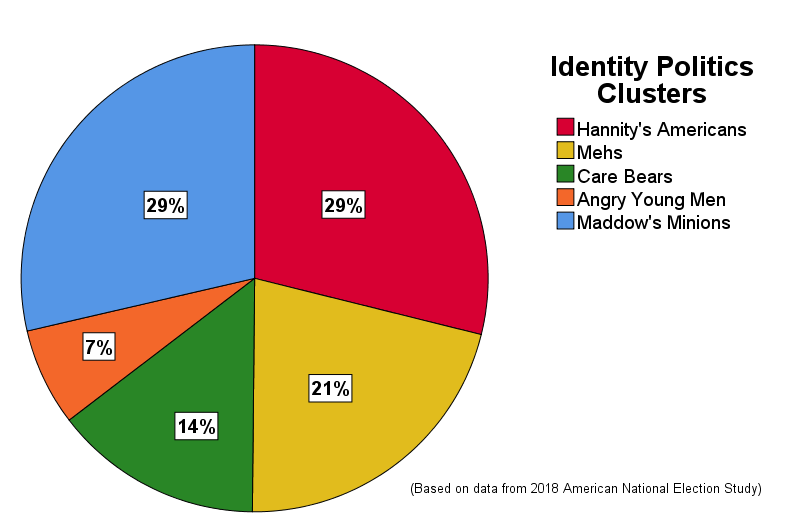

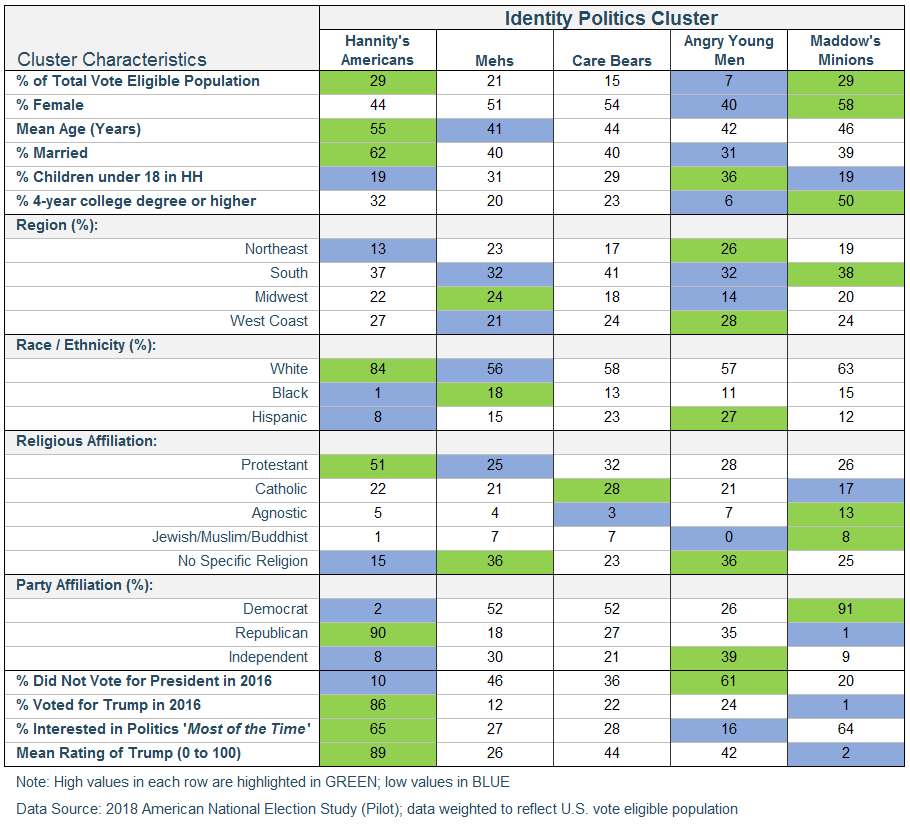

For now, I will describe the five macro-clusters represented in Figure 2 by their relative population size.

Figure 2: The Identity Politics Cluster Sizes (U.S. eligible voter population)

Data source: 2018 American National Election Study; Analytics and Segmentation by Kent R. Kroeger

The two largest IPCs are Hannity’s Americans (29%), a cluster containing mostly Republicans, and its counterpoise, Maddow’s Minions (29%), a cluster composed almost entirely of Democrats.

The next largest cluster is the Mehs (21%) — distinguished by their general ambivalence or lack of affinity for any specific person or group. The Care Bears (14%), in contrast, like everybody (except President Trump). And, finally, the Angry Young Men (7%), the smallest cluster and notable for their dislike of pretty much everybody (except President Trump and white people).

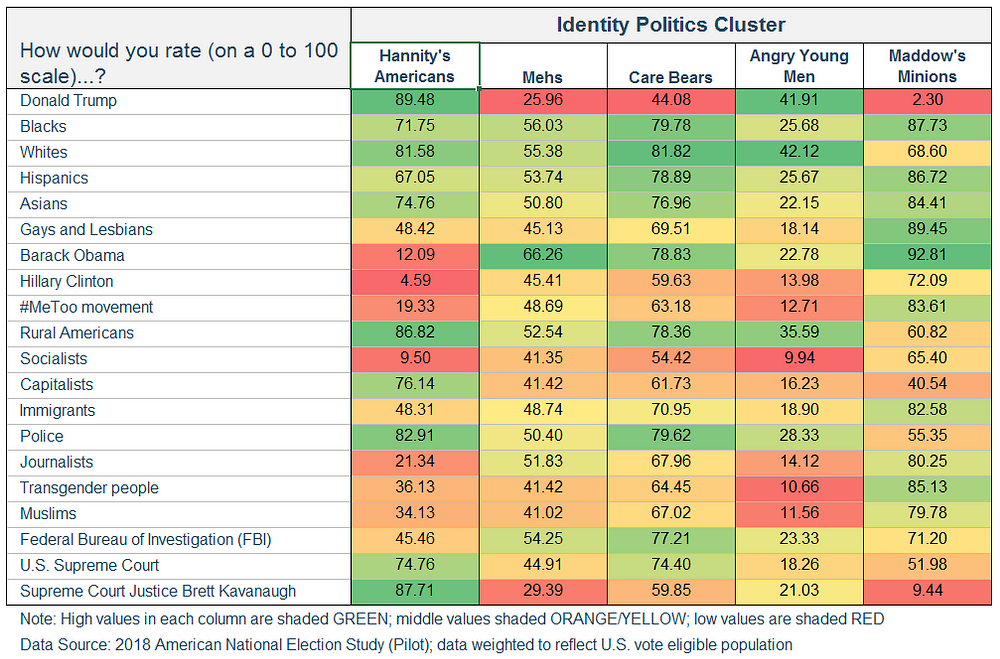

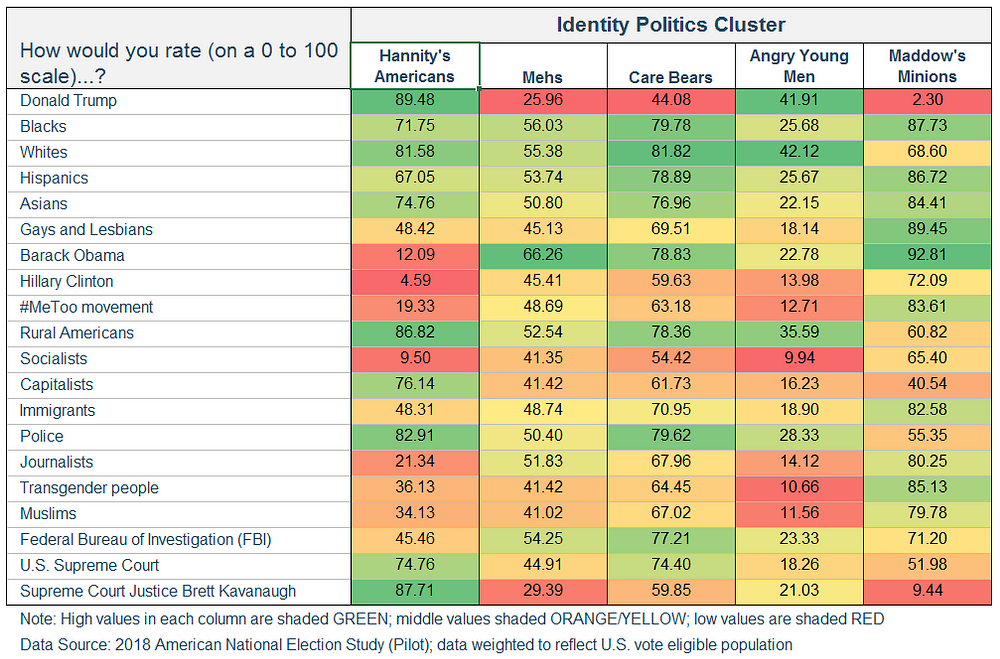

The IPCs distinguish themselves by their average ratings of the various identity groups, individuals and organizations (see Figure 3). For example, among the five clusters, Hannity’s Americans rate Donald Trump the highest (mean rating = 89.5). Not surprisingly, Maddow’s Minions can only muster an average rating of 2.3 for the current president. I don’t think he’s a fan of Rachel Maddow any way.

On the other end of the scale, Hannity’s Americans rate Hillary Clinton a 4.6 and Barack Obama only slightly better at 12.1.

Figure 3: The Identity Politics Cluster Sizes (U.S. eligible voter population)

Among the racial and ethnicity-defined identity groups, Hannity’s Americans and Maddow’s Minions are roughly similar in their ratings for Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians when viewed as a deviation from the cluster’s group mean (i.e., the color-coding in Figure 3). However, where Maddow’s Minions rate whites lower than Blacks, Hispanics or Asians, Hannity’s Americans rate whites higher than those groups.

However, on other identity groups, the differences are stark. Hannity’s Americans, on average, rate the #MeToo movement a 19.3, compared to 83.6 for Maddow’s Minions. Hannity’s Americans rate socialists a 9.5, on average; while Maddow’s Minions give them a 65.4 rating.

The two biggest clusters are predictable considering their strong partisan composition and 30 years of a growing partisanship divide within the American public. By now, anyone that is a strong partisan should know the ‘in’ groups from the ‘out’ groups. Hannity’s Americans like capitalists, rural America, and the police; Maddow’s minions like immigrants, transgender persons and journalists. We didn’t need a survey to tell us that.

Not as obvious are the three ‘middle’ clusters. They represent 40 percent of the eligible voter population, a potentially relevant force in any election (though all three clusters have much lower voter turnout rates than the two partisan clusters; see Figure 4).

The Mehs are the least interesting in terms of variation across their identity group ratings. Their average rating ranges between 40 and 55 — with two exceptions: They like Obama (66.3%) and dislike Trump and Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh (26.0 and 29.4, respectively). Spoiler alert: In Figure 4 you will notice Mehs skew female.

The Care Bears skew even more female than Mehs but have a greater affinity for the various identity groups. They like almost everybody (except, again, Trump — I think he might have a problem with the ladies).

In contradistinction are the Young Angry Men who dislike everybody, except Trump, whites, and rural Americans — but, frankly, this cluster isn’t thrilled with them either as all fail to break the rating scale’s midpoint (50).

Figure 3: The Identity Politics Cluster Sizes (U.S. eligible voter population)

How can find these cluster members?

If a political party or campaign were to target any of these five clusters, Figure 4 would be a good place to start that process.

I won’t cover here every demographic and behavioral detail for the IPCs. Hopefully, Figure 4 makes those characteristics clear. A simple summary must suffice for now:

Hannity’s Americans are largely white, Christian, older Republicans that voted for Trump and are interested in politics.

Maddow’s Minions are largely white, educated, female Democrats (no children) that did not vote for Trump and are interested in politics.

Mehs are largely young, racially diverse and less likely to be religious.

Care Bears are largely in the middle on most attributes, but have a high percentage of Catholics and a low percentage of agnostics.

And, lastly, Angry Young Men are…well…young men. But a sizable number have children in their household, are racially diverse, are political independents, and live on either the East or West Coasts. The quality they do not possess is an interest in politics which explains why most of them did not vote in 2016. For political mobilizing and vote harvesting purposes, this group would be a slog for even the Republicans.

Figure 4: The Identity Politics Cluster Sizes (U.S. eligible voter population)

Implications

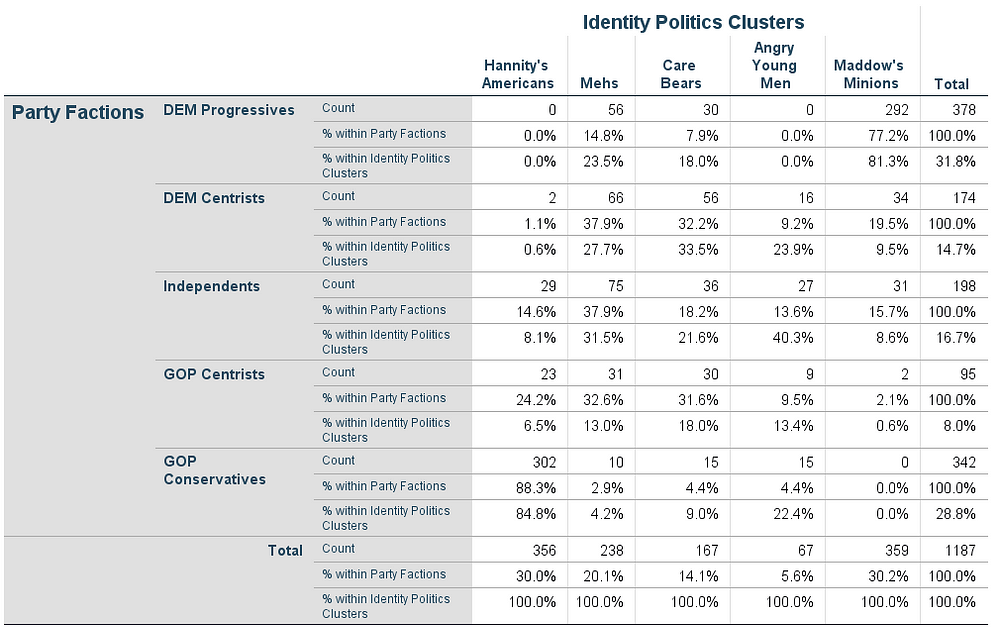

After running these clusters past a former colleague, now a Democrat-aligned pollster, a question arose: How do the two major factions within the Democratic Party (Progressives and Centrists) relate to the identity politics clusters?

Figure 5 cross tabulates the IPCs by the party factions identified in a previous segmentation analysis (using the 2018 ANES data). The association between the two segmentations — one formed using only policy-related questions and one formed using the identity group affinity questions — is strong.

Figure 5: The Identity Politics Cluster Sizes by Party Factions

Data source: 2018 American National Election Study; Analytics and Segmentation by Kent R. Kroeger

Most of Maddow’s Minions (81%) are also Democrat Progressives. Similarly, most of Hannity’s Americans (85%) are also GOP Conservatives.

As to where Democrat Centrists are categorized among the IPCs, it is more complicated. Over 70 percent of them split between the Mehs and Care Bears. Only 20 percent of them belong to Maddow’s Minions. Likewise, GOP Centrists mostly divide themselves between the Mehs and Care Bears.

This is a key strategic finding. GOP and Democrat Centrists share considerable common ground with respect to identity politics and actually divide in a similar fashion — roughly one-third are disconnected or ambivalent towards identity politics (Mehs), one-third demonstrate caring across a broad range of identity groups (Care Bears), and most of the rest are fully engaged in identity politics. If identity politics is an important focal point for the Democrats in the 2020 presidential election, their Gettysburg may come down to the battle for the vast majority of Care Bears — a population segment that is predominately female and votes. If the Democrats don’t win this group — by a lot — they don’t win the presidential election.

A superficial read of recent stump speeches by the Democratic presidential candidates — FiveThirtyEight’s Adam Kelsey posts summaries and links to these speeches here — highlights the prominent role identity politics is already playing in the 2020 campaign.

Oppression. Privilege. Reparations. Dignity. Reproductive rights. Gay rights. Racial justice. Justice. Justice. Justice.

All words and phrases peppered throughout the candidate speeches. Even those candidates centered on material, economic issues — Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren — explicitly link those issues to identity politics.

Its not simply about fighting climate change anymore, say Democrats, its now about repairing racial injustices and income inequities bred by our carbon-based energy consumption. Slow wage growth and growing income equality can’t merely be addressed through economic policy, we must now tear down institutions that protect privilege and create new, more equitable ones that correct for the damage caused by a long history of race and gender-based oppression.

These are the mainstream arguments being made now by the leading Democratic presidential candidates. And why shouldn’t they? Two-thirds of their party is composed of progressives who hold strong affinities towards groups found at the medial point of today’s identity politics.

But if the Democratic Party nominee continues with this strategy in the general election, will it work with centrist and independent voters, a good share of whom will be needed if the Democrats are to regain the White House?

A deeper drilling down into the identity politics clusters would help answer that question, but even these clusters viewed at the 30,000-foot-level, as done in this essay, lead me to believe YES is the answer.

The two election front line groups — Mehs and Care Bears — skew female and Democrat. The numbers are simply in the Democrats’ favor.

Sorry my GOP friends. But based on what I am seeing, the Democrats are not imploding under the weight of identity politics — they are on message with the majority of Americans.

- K.R.K.

Data and SPSS computer codes available upon request to: kroeger98@yahoo.com