By Kent R. Kroeger (NuQum.com, March 16, 2020)

Two news stories this morning (March 16, 2020) caught my attention.

The first story concerned Utah Jazz basketball player Donovan Mitchell who was diagnosed to have the coronavirus (2019-nCoV) and apparently became infected through his close contact with fellow player Rudy Gobert, who also tested positive for the virus.

“I’m asymptomatic,” Mitchell told ABC’s “Good Morning America” on Monday. “I don’t have any symptoms. I could walk down the street (and) if it wasn’t public knowledge that I was sick, you wouldn’t know it. I think that’s the scariest part about this virus. You may seem fine, be fine. And you never know who you may be talking to, who they’re going home to.”

We should assume there are thousands of Donovan Mitchell’s roaming our country feeling healthy and promoting the spread of COVID-19.

The second story I heard on public radio station WNYC this morning. While being interviewed on the The Brian Lehrer Show, Dr. Irwin Redlener, professor of pediatrics and director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University, told the NPR audience that the emphasis for containing COVID-19 must focus on those already sick and not trying to test as many people as possible for the virus.

I am not a medical doctor or epidemiologist, but as a statistician, those two stories raise a number of red flags.

First, addressing Dr. Redlener’s comments, to suggest our nation’s efforts must be focused on those already sick is a mea culpa suggesting our hope of limiting the spread of this virus is a misuse of limited resources.

According to many health care experts, our health care infrastructure is under too much stress taking care of those infected with 2019-nCoV to take on the responsibility of measuring its incidence.

If he is right, trying to measure the prevalence of COVID-19 in the population is purely an academic exercise that distracts from saving lives.

But then came the Donovan Mitchell story. Infectious disease experts and epidemiologists readily admit they don’t know the percentage of COVID-19 carriers are asymptomatic (i.e., they show no symptoms of the virus while they are contagious).

How could they know? This is a new virus. They call it ‘novel’ for reason.

It seems reasonable to assume the number Americans currently infected with the coronavirus is greater than the 4,464 confirmed cases reported to the WHO (as of 16 March).

_________________________________________________________________

In a previous essay I estimated there were almost 20,000 “unmeasured” Americans infected with the coronavirus (as of 14 March). However, my effort was exploratory, not conclusive, if only because I assume the reported U.S. numbers up to now are an underestimate caused by a flawed government response to the virus. However, an equally valid conclusion could be that the relative low number of U.S. confirmed cases is the result of successful state and federal government efforts to contain the virus.

Frankly, how can we single out the Trump administration when so many European and economically-advanced countries have made the same mistakes? If anything, this crisis exposes the inadequacy of the advanced economies, in general, to manage global pandemics.

One exception is South Korea which saw its number of new confirmed cases start to decline over a week ago (see the orange line in the chart below).

According to experts, South Korea’s aggressive testing effort deserves credit for this coronavirus success story. From the moment the coronavirus starting appearing in South Korea the country has fielded almost 190,000 tests — approximately 3,690 tests per 1 million people.

In contrast, as of 8 March, the U.S. has conducted only 8,400 tests resulting in 213 positive cases (keep in mind, some patients have been tested more than once). If my conclusion is correct that 19,000 Americans currently have coronavirus but have not been tested, the U.S. will need 790,000 tests kits just to test these “unmeasured” people. But even that number is an underestimate as it does not include the Americans who are still to get COVID-19.

Conservatively, if the test’s 2.5 percent yield holds, the U.S. needs millions of test kits to identify the majority of Americans infected by the coronavirus. In that light, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’ recent announcement that his state will be distributing 500 more test kits to hospitals and private labs feels grossly inadequate.

Even so, Dr. Redlener’s concern has merit that too much emphasis on testing will take resources from hospitals and doctors tasked with treating those already sick. Health care professionals are already reporting shortages due to this pandemic.

Therefore, should the U.S. even try to diagnose every coronavirus carrier?

_________________________________________________________________

Dr. Redlener’s answer appears to be ‘No.’ And he may be right, but my question is: Why should the wealthiest country in the world need to choose between treating its citizens for a deadly virus and accurately measuring the prevalence of this virus in the general population?

I believe its a trade-off we don’t need to make and will only cost us more in the long run as “unmeasured” coronavirus carriers will extend this outbreak even farther into the future.

“Asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic transmission are a major factor in transmission for Covid-19,” Dr. William Schaffner, a professor at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, told CNN. “They’re going to be the drivers of spread in the community.”

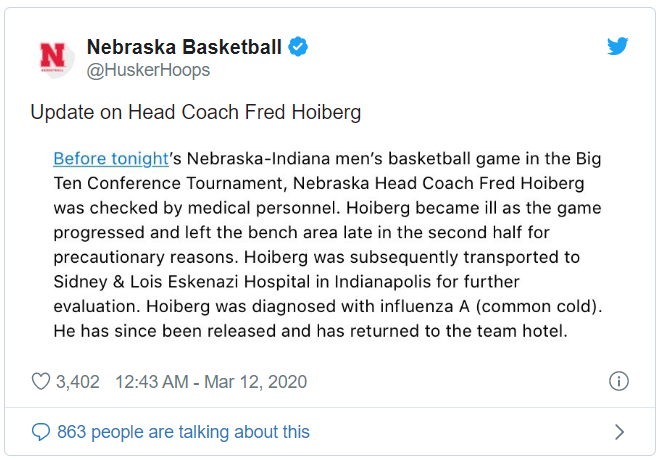

I was reminded of Dr. Schaffner’s warning when I read the story of Nebraska basketball coach Fred Hoiberg being taken to the hospital after he showed flu-like symptoms during his team’s Big 10 basketball tournament game against Indiana. Hospitalized after the game, it was determined Coach Hoiberg had the normal flu (Influenza-A) and not COVID-19. All’s well that ends well, right?

No, not right.

Coach Hoiberg didn’t fall ill during the game, he felt ill before the game. In fact, he felt bad enough to visit the Big 10 tournament doctor an hour before the game started. And what did the tournament doctor conclude? Despite showing flu-like symptoms — in the middle of the coronavirus crisis — the doctor decided Hoiberg was OK to coach from the bench.

If Hoiberg and that Big 10 doctor still have jobs today, the University of Nebraska and the Big 10 should be ashamed of themselves.

Being a self-obsessed college basketball coach is not an excuse for being so dismally unaware of the world around you that you think its OK to potentially expose hundreds of players and fans to a pandemic virus. What was Hoiberg thinking?

“Please let it be known that I would never do anything that would put my team, family or anyone else in harm’s way. I was feeling under the weather on Wednesday and we felt the right thing to do was to get checked by a tournament doctor prior to our game in the Big Ten Tournament against Indiana. Once that medical official cleared me, I made a decision to coach my team. I would like to thank event staff for their care and professionalism. Also, thank you to everyone who has reached out for your support. This is a scary time for all of us. Let’s offer our thoughts and prayers directly to those affected with Coronavirus.”

Hoiberg proves you don’t have to be smart to be a NCAA Division I basketball coach, but the tournament doctor? What was his excuse for letting Coach Hoiberg into the arena? There is no possible way this doctor could have tested Hoiberg for the coronavirus by examining him right before the game’s tip-off. Clearly, the doctor was more afraid of affecting the outcome of a Big 10 basketball game between two of the conference’s worst teams than he was about potentially spreading a deadly virus to hundreds of people.

This Big 10 tournament doctor needs to appear before a medical review board to defend why he still has a medical license.

________________________________________________________________

If my March 14th analysis is accurate, there may be nearly 20,000 Americans walking around with the coronavirus but undiagnosed. How do we find them?

From a statistical sampling perspective, the task is daunting. According to my analysis on 14 March, the incidence of undiagnosed coronavirus carriers was 20,000 ÷ 327 million U.S. citizens (or about 1-in-16,000).

Any effort to find these 20,000 people is helped by the fact that these cases will tend to be geographically clustered. We already see this clustering among diagnosed coronavirus cases in the U.S. (e.g., New Rochelle, NY; Biogen conference in western Massachusetts, Life Care Center of Kirkland, near Seattle, WA). This clustering is a function of the coronavirus’ R0— an estimate of the number of people an average infected person spreads the virus to — which the current evidence indicates is between two and three, making it substantially more contagious than the typical flu.

For sampling purposes, a higher R0 assists in detection. Find one infected person and you are likely to find many more.

A back-of-the-envelope estimate of the testing sample sizes needed to detect and isolate areas containing infected persons goes as follows:

First, let us assume the probability distribution of those infected follows a binomial form:

where f(x) is the probability x is the number of undetected infected persons in a sample of size of n. The value of p is the hypothesized proportion of undetected infected persons in the population.

From the above equation we can begin to estimate the sample sizes needed to find coronavirus carriers.

Let us start with a simple case: Assume you live in a city of 16,000 people. Based on our hypothesized incidence rate of 1-in-16,000, there may be one person in your city with the coronavirus. How do we find this person? We test a random sample of the city population, but since tests are expensive to administer, we want to minimize the size of our sample. Therefore, how big does the sample need to be to have a reasonable chance of detecting this one infected person?

Acceptance sampling methods allow us to find a happy middle ground between a 100-percent-census (which is cost prohibitive) and no measurement at all.

Since we consider a population “infected” (and, presumably, quarantined) if we find even one infected person, acceptance sampling (at a General II inspection level) suggests we need a sample size of 315 randomly selected people.

Scaling up to a larger population, a city of 100,000 would be stratified into 6 distinct geographic areas with approximately 16,000 people in each geographic strata. Again, we’d take a sample of 315 people in each strata for a total sample of 1,890 people.

Scaling up further to the entire U.S. population (approx. 327 million people), we would need to test 6.4 million people to have a reasonable assurance of detecting where the most infection cases are present.

Since it takes more than one test kit in some cases to test one person, we could be looking at 10 million test kits or more.

Not going to happen.

Even if we select a lower testing standard (i.e., a greater tolerance for missing some of the lesser infected areas), we’d still be looking at almost 5 million test kits.

A country that produces 1 billion cans of wet dog food every year can certainly muster up the resources to produce 5 million coronavirus test kits on short notice.

Furthermore, even if this country could produce them quickly, the resources necessary to distribute and administer these test kits would overwhelm our already fragile health care system.

Thus, this is why social distancing and self-quarantines are indispensable in containing the coronavirus and all future pathogens that will threaten us.

As Dr. Redlener noted on WNYC, we can’t detect and treat everyone.

_________________________________________________________________

Still, sampling methods such as acceptance sampling need to become standard practice among our front line health professionals, particularly at the beginning of a potential pandemic when its final social costs are still unknown.

The U.S. cannot afford to passively identify infected persons as we mostly have so far with COVID-19. Instead, the U.S. must proactively identify infected persons as South Korea and China are systematically doing now. We need to flatten the infection curve as best we can and sampling can help us efficiently do that.

Unfortunately, during the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, our state and federal governments appear unequipped and untrained to do that level of proactive detection.

As South Korea has proven, measurement is key to fighting pandemics like COVID-19.

Bob Galvin, a former Motorola executive and co-creator of the Lean Six Sigma quality improvement method, once said, “Companies must measure or die.” In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, that warning is literally true.

- K.R.K.

Data sets and statistical codes referenced in this essay are available upon request to: kroeger98@yahoo.com