By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; March 21, 2020)

For three years the U.S. news media wasted our time promulgating a conspiracy theory that candidate Donald Trump and his campaign conspired with the Russians to steal the 2016 presidential election.

It was never true. Not even a little bit true. It was a conspiracy theory built on half-truths, coincidences, profit motives and malicious, partisan intentions.

And now, with the coronavirus pandemic, we are witnessing a new bull market for conspiracy theories:

- In the midst of a contentious trade war with China, the U.S. military planted the coronavirus in China to weaken their position,

- The Chinese military used the coronavrius outbreak to end the democracy protests in Hong Kong,

- The coronavirus was released due to a lab accident in Wuhan, China,

- The pharmaceutical companies created the coronavirus knowing they already had the drugs necessary to treat it (thereby enriching themselves),

There are many more conspiracy theories about the coronavirus. Too many. All predicated on nothing more than circumstantial evidence — mere coincidences — and implanted into the world’s information bloodstream where they prosper, morph, and instill a pernicious type of distrust in a vulnerable segment the general population desperately looking for explanations for why they are now terrified to leave their homes.

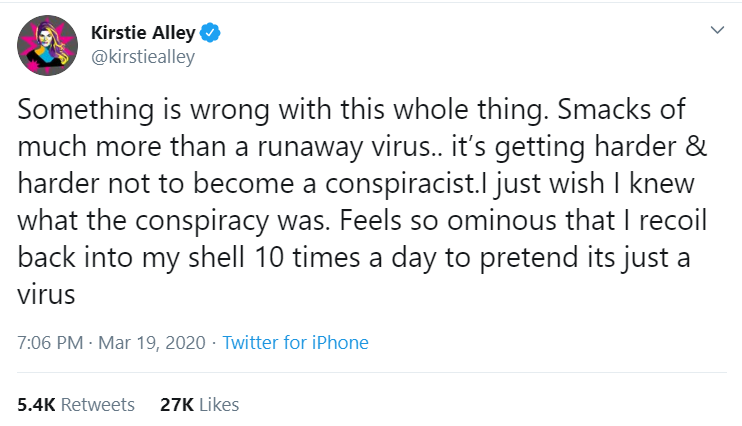

Perhaps actress Kirstie Alley describes many of us are attracted to conspiracy theories regarding the coronavirus (no matter absurd their internal logic):

Many of us have a preternatural need to explain events and phenomena that shake our security and sense of stability.

Sometimes we just can’t accept that random coincidences happen without some larger purpose or meaning. Who wants to live under the constant threat of random chance?

_________________________________________________________________

One of the first challenges greenhorn intelligence analysts face in the U.S. Intelligence Community — as they analyze data and information related to their area of expertise —is learning how to distinguish random coincidence from significance.

Two or more events can appear through their ordering or simultaneity to be significantly related — when, in fact, they are not.

We’ve all said this at one point in our lives: What are the chances?

Two years ago, on an unremarkable Saturday morning, I realized I had not done laundry for a while. I despise doing laundry. In my 50s now, I have never separated whites from colors during the washing process. Never. Not once.

On that day, I couldn’t find even one clean shirt to throw on before getting my morning coffee and donut at the local supermarket. In desperation, I pulled a garbage bag full of old shirts out of my closet that I had never unpacked since moving from Iowa to New Jersey three years ago.

I knew if I dug down too deep in the bag, grody smells might escape, so I just yanked out what was on top: a crisp white t-shirt I had purchased in commemoration of Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s February 2012 visit to Iowa.

The t-shirt had never been worn. It was meant to be a souvenir. But, in a desperate moment, I threw it on — along with some jeans — and drove to the market.

While waiting for my double-shot espresso, I decided to pick up some recliner chair food for watching the day’s schedule of college basketball: some deli meats, sliced cheese, fresh bread and Nabisco animal crackers. As I took a tight turn into the cracker aisle, I was forced to make a Euro step move to avoid a man walking out of the same aisle.

We apologized to each other and instantly realized something bizarre had just happened: we were both wearing a Xi Jingping (Welcome Back to Iowa) t-shirt.

What are the chances?!

We both spit out a laugh and chatted long enough to discover we had lived in Des Moines around the same time and were professionally interested in China.

But what were the chances that we’d wear those identical t-shirts on the same morning, in the same supermarket, in the cracker aisle, in Pennington, New Jersey?

No need to do the math. The probability was not substantively different from zero.

Yet it happened. It was a random coincidence — nothing more significant than that.

________________________________________________________________

Other coincidences are not as improbable, even if we think they are.

The classic case, often used in introductory college statistics courses, is the Birthday Problem: What is the probability that at least two students in a classroom of 30 share the same day of birth?

The typical first-year statistics student thinks the chances are slim; in my experience, they will guess something well under 50 percent. There are 365 days in a year, after all. Two randomly selected people have a 0.27 percent chance of sharing a day of birth. How much better are the chances in a room of 30 students?

It turns out, a lot. Throwing a simple probability formula against the problem, the chances of at least two students in a class of 30 sharing the same day of birth is 71 percent.

The lesson in these two coincidence examples is that people are prone to making judgment errors in presence of natural randomness.

The Xi Jinping t-shirt story is an illustration of Littlewood’s Law which states that a person can expect to experience events with an odds of one-in-a-million at the rate of one per month.

It’s not a formal scientific law, but it brings attention to the omnipresence of improbability in our daily lives. The improbable is everywhere.

For example, what are the chances that as I write this essay wearing only one sock, my son cries out about not being able to find his science class notebook, at the same time my dog starts barking at the deer in our backyard, at the precise moment my wife walks into the kitchen and complains that I didn’t wash the dishes from last night’s dinner in which I used a new Indian curry recipe she was given while in India last January?

In combination with how generally poor we are at assigning accurate probabilities to even common events — an intrinsic cognitive flaw in how our brains are wired — natural randomness can bring significant stress to our lives.

________________________________________________________________

Science writer Michael Shermer calls this cognitive flaw “folk numeracy,” which he defines as “our natural tendency to misperceive and miscalculate probabilities, to think anecdotally instead of statistically, and to focus on and remember short-term trends and small-number runs.”

As a result, we frequently exaggerate the probabilities of some threats (e.g., being a victim of terrorism) and wrongly minimize others (e.g., getting in a car accident while we are driving).

In his book, How We Believe, Shermer describes the human brain as evolving out of necessity into a pattern recognition machine that creates structure and meaning so we can navigate our surroundings with minimal stress. Our brain is an efficient uncertainty reducer that aids us in survival and reproduction, says Shermer.

Psychologist R. Nicholas Carleton, an expert in anxiety disorders, ties the human need to recognize patterns to a deep-seated fear-of-the-unknown — what he calls, our fundamental fear.

Not only is fear-of-the-unknown inherent to the human species, according to Dr. Carleton, it is “distributed and normally in the population.” Some people have more of that fear than others — and some less. As such, someone with a strong fear-of-the-unknown but relatively poor at bringing order to their world (e.g., assigning accurate probabilities to events) will potentially suffer high levels of anxiety.

________________________________________________________________

Coincidences are manifestations of chance and our strategies for interpreting these improbabilities can vary significantly.

Most often, the statistician in me sees the joint occurrence of improbable events (coincidence) as unremarkable. Unless you bring a defensible theory and independent data to the explanation, don’t waste my time.

Yet, there are times when coincidences do reveal something more causally significant. As mystery writer Simon Van Booy once put it, “Coincidences often mean you’re on the right path.”

The current controversy swirling around Tennessee Senator Robert Burr comes to mind. According to a March 19 ProPublica story, “soon after he offered public assurances that the government was ready to battle the coronavirus, the powerful chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, Richard Burr, sold off a significant percentage of his stocks, unloading between $628,000 and $1.72 million of his holdings on Feb. 13 in 33 separate transactions.”

Days later, worldwide stocks markets dropped precipitously. Now that is some coincidence. Actions by at least one other U.S. politician is under similar suspicion.

Time will tell if Senator Burr’s actions were criminal, but the story highlights an example where coincidence cannot be dismissed out-of-hand as random chance.

Occasionally, even if rarely, conspiracy theories are right. The trick is knowing when.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: kroeger98@yahoo.com