By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, June 3, 2020)

We, Americans, are living in dark times, though far from the darkest of times.

And, no, I do not blame Donald Trump for George Floyd’s death and the subsequent rioting, though Trump’s organic inability to show empathy for other humans crushes any hope that his words will lead us from this dark place.

And I also don’t blame Joe Biden, the author of the 1994 Crime Bill that many claim is responsible for this nation’s high incarceration rate. Along with his daily offering of platitudes from his basement, bland even by centrist candidate standards, Biden has singled out Trump’s cavalier attitude about police violence for creating an environment where something like the Floyd tragedy was inevitable.

More troublesome about Biden, however, is his lifetime penchant for exaggerating (and, in some cases, manufacturing) stories of his political accomplishments. As comedian Jimmy Dore describes the presumptive Democratic nominee: “Joe lies about his record more often than he blinks.”

Not exactly true, but closer to the truth than comfortable.

“I’m the most progressive presidential candidate in this race,” was Biden’s go-to line during the 2020 nomination race when pressed to cite his progressive credentials. “On health care, pay equality, voting rights, climate change, I’ve led.”

But, in words and in deeds, Biden doesn’t look so progressive. In the current campaign, Biden draws significant campaign contributions from health care and pharmaceutical executives, and even launched his 2020 election effort with a fundraiser co-hosted by Dan Hilferty, CEO of Independence Blue Cross.

Biden’s 2020 campaign is also central to the health care lobby’s effort to discredit Bernie Sanders’ Medicare-for-All proposal.

“Part of a multi-front corporate effort to defeat the policy,” according to journalist Branko Marcetic, author of Yesterday’s Man: The Case Against Joe Biden. “In Biden, the health care industry has found its guy.”

On climate change, a similar story emerges. While Biden did introduce the Global Climate Protection Act (GCPA) of 1987, the first of its kind, the GCPA merely funded a task force to develop a national strategy for addressing global warming.

The surge in U.S. fossil fuel production under the Obama administration is one thing, but nothing highlights Biden’s internal contradictions on climate change than the work he did as vice president to engineer a $50 million aid package to Ukraine for the development of its shale gas infrastructure and expanding its fossil fuel industry. At a time when the Paris Agreement was trying to get the country’s to draw down their greenhouse gas emissions, Biden was helping Ukraine do the opposite.

In a scathing rebuttal to Biden’s claim as a “leader on climate change,” GQ’s Luke Darby recently wrote: “Biden’s pitch for his climate policy is that it’s the most realistic. That’s true in a sense — it offers the fossil fuel industry the least disruption and headache possible while gently trying to reduce carbon emissions. But his plan doesn’t seem realistic in terms of actually fighting climate change.”

Biden banks on the credulity of the American voter and on no subject does Biden push those limits more than when he talks about his record on criminal justice.

When asked by CNBC’s John Harwood if he was ashamed of the 1994 Crime Bill he authored, Biden replied, “Not at all. When you take a look at the money in the crime bill, the vast majority went to reducing sentences, diverting people from going to jail for drug offenses and into drug courts and providing for boot camps instead of sending people to prison.”

Biden continued: “(The 1994 Crime Bill) put a hundred thousand cops in the street when community policing was working neighborhoods were not only safer but they were more harmonious. The reason why the cops originally opposed my hundred thousand cops from this community policing piece is because it’s highly intensive. It means they literally got out of the cars and learned who owned the local drug store and local neighborhood bar and they were engaged in the neighborhood which built confidence (in those neighborhoods).”

Its a nice story, but like most anything a politician claims, the truth lies somewhere between the politician’s rhetoric and their sharpest critics.

One of Biden sharpest critics, President Trump, while praising his own criminal justice reform accomplishments, tweeted in May that “anyone associated with the 1994 Crime Bill will not have a chance of being elected. In particular, African Americans will not be able to vote for you.”

A bold statement, but misses the mark with its focus on the 1994 Crime Bill, a piece of legislation that some policy analysts consider more impactful in its symbolism than its substance.

According to Udi Ofer, the American Civil Liberty Union’s Director of the Campaign for Smart Justice: “The 1994 crime bill gave the federal stamp of approval for states to pass even more tough-on-crime laws. By 1994, all states had passed at least one mandatory minimum law, but the 1994 crime bill encouraged even more punitive laws and harsher practices on the ground, including by prosecutors and police, to lock up more people and for longer periods of time.”

But the other significant impact of the 1994 Crime Bill was how it changed the Democratic Party’s political approach to criminal justice reform.

Writes Ofer: “Under the leadership of Bill Clinton, Democrats wanted to wrest control of crime issues from Republicans, so the two parties began a bidding war to increase penalties for crime, trying to outdo one another. The 1994 crime bill was a key part of the Democratic strategy to show that it can be tougher-on crime than Republicans.”

Biden was a central player in that strategic shift within the Democratic Party.

Given that context, the current crisis over George Floyd’s death by a Minneapolis police officer may be less of a partisan advantage for the Democrats than commonly assumed.

Is Trump culpable in Floyd’s death? No, but…

President Trump’s defense on the question of police violence is unnecessarily weak. Inexplicably, he has repeatedly promoted police violence against crime suspects, both as a candidate and as president. The following video (and others like it) is exhibit number one:

“I’d like to punch them in the face,” Trump has said on more than one occasion.

President Trump’s too numerous and artless incitements for police violence may not be responsible for any specific excessive use of force case carried out by law enforcement, but he’s still culpable for giving spiritual support to such tactics. Police culture in the U.S. has always been too permissive in how it allows officers to apply potentially deadly force and Trump, through his frequently disordered rhetoric, has reinforced those counterproductive rules of engagement.

Joe Biden’s relationship with U.S. crime and law enforcement policy is more complicated and requires a significant amount of effort to reconcile his legislative record with his campaign rhetoric.

Spoiler alert: Joe Biden’s record on crime and police enforcement is not as constructive as CNN and MSNBC want you to believe, but its not as egregious as others suggest. It’s nuanced, while still being bad.

Any discussion on Joe Biden and crime law must start with Reagan

While political pundits and Biden critics focus on the 1994 Crime Bill, the real story behind Biden’s view on criminal justice goes back further in time.

The 1980 election of Ronald Reagan was a traumatic experience for Democrats (myself included). Here he was, a far-right conservative and former B-movie actor, winning the White House at a time when the U.S. was still healing from the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal.

The 1980 election felt as if the country learned nothing since John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 and the Vietnam War.

Had Reagan’s presidency failed, the FDR-New Deal wing of the Democratic Party would have enjoyed both consolation and reinvigoration heading into the 1984 presidential election. Instead, the party suffered the worst defeat in its history.

In that same 1984 election, U.S. Senator Joe Biden (D-Delaware) won re-election by a 20-percentage-point margin; and, to the southwest of Delaware, two other young Democrats, Al Gore (D-Tennessee) and Bill Clinton (D-Arkansas), won a U.S. Senate and gubernatorial election, respectively, by even larger margins.

For good reason, all three were rising stars within the Democratic Party.

While strategically adopting liberal positions on some social issues (women’s rights, the environment) but not others (abortion, criminal justice), these New Democrats — loosely organized through the Democratic Leadership Council — were best distinguished from the Democratic old guard by their willingness to work with the corporate sector in crafting policy solutions, as opposed to aligning against those same business interests.

The working-class-versus-big-business model the Democrats had used to win 8-out-of-12 elections between 1932 and 1976, was now 0–2 going into the 1988 election. [Economic progress will do that.]

In the 1988 Democratic nomination race, Joe Biden and Al Gore were dark horse favorites, but eventually lost to the party establishment favorite — Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis.

Side bar: Few remember how the Reverend Jesse Jackson received nearly 30 percent of the Democratic primary vote in 1988, finishing a solid second to Dukakis, and who aggressively forced the Democratic Party to make its nomination more democratic, directly paving the way for a young U.S. Senator from Illinois in 2008 to take down the Democratic establishment candidate, Hillary Clinton. There is no Barack Obama without Jesse Jackson.

If the Democratic Party establishment is good at anything, it is good at misreading mainstream America.

Where the 1980 Reagan victory was traumatizing but rationalizable, George H. W. Bush’s victory in 1988 was deflating. The Democratic Party couldn’t even beat a low-charisma, Republican hack.

Contributing to Dukakis’ defeat was a Bush political ad crafted by the Republican’s dark lord, Lee Atwater. The ad featured Willie Horton, a convicted murderer who was granted 10 weekend prison passes during Dukakis’ tenure as Massachusetts governor and who used his last one to assault a Maryland man and rape the man’s fiance.

On the issue of criminal justice, the Democratic Party was never the same after Willie Horton; and Joe Biden, who had already helped write three substantive, Republican-supported crime bills before the 1988 election, became one of the party’s most important voices on the subject after that election.

As a volunteer for the 1988 Jesse Jackson presidential campaign, I saw in real-time the rise of the New Democrats over the New Deal old guard between the 1988 and 1992 presidential elections. Presidential candidates like Missouri’s Richard Gephardt and California’s Jerry Brown tried to carry on the FDR tradition, but to no avail. By 1992, the Democrats were determined they would not lose to H. W. Bush again without putting up a credible fight. That meant, in part, abandoning party doctrine on criminal justice — and no Democrat did that better than Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton.

Using a mostly contrived controversy with female rapper Sister Souljah, Clinton positioned himself to the voting public as willing to dispense with the party’s historically criminal-sympathetic views on criminal justice.

Cynical or not, the Clinton Sister Souljah tactic was effective and he won the 1992 election.

At the focal point of that ideological shift within the Democratic Party was Senator Joe Biden, who happened to already chair Senate Judiciary Committee in 1992.

The 1994 Crime Bill in context

President Clinton’s job approval plummeted to 37 percent within the first year of his presidency, driven down partly from a failed effort to produce a viable health care reform package he had promised during the 1992 campaign.

However, after successfully pushing ratification of the North American Free Trade Agreement through the U.S. Senate in November 1993, Clinton’s public support experienced a significant, if only temporary, rise.

In the midst of his approval rise in late-1993, Clinton pushed for a crime bill that would place himself (and his party) to the right of the Reagan-era 1984 crime bill, a piece of legislation that, among other things, increased sentences for felons committing crimes with firearms and who had also been convicted of certain crimes three or more times. The 1984 Crime Bill also increased federal penalties for the cultivation, possession, or transfer of marijuana.

With the help of U.S. Representative Jack Brooks (D–TX) and Senator Biden in 1993, Clinton wanted a crime bill that would ensure his presidency and party would not be perceived as weak on the issue.

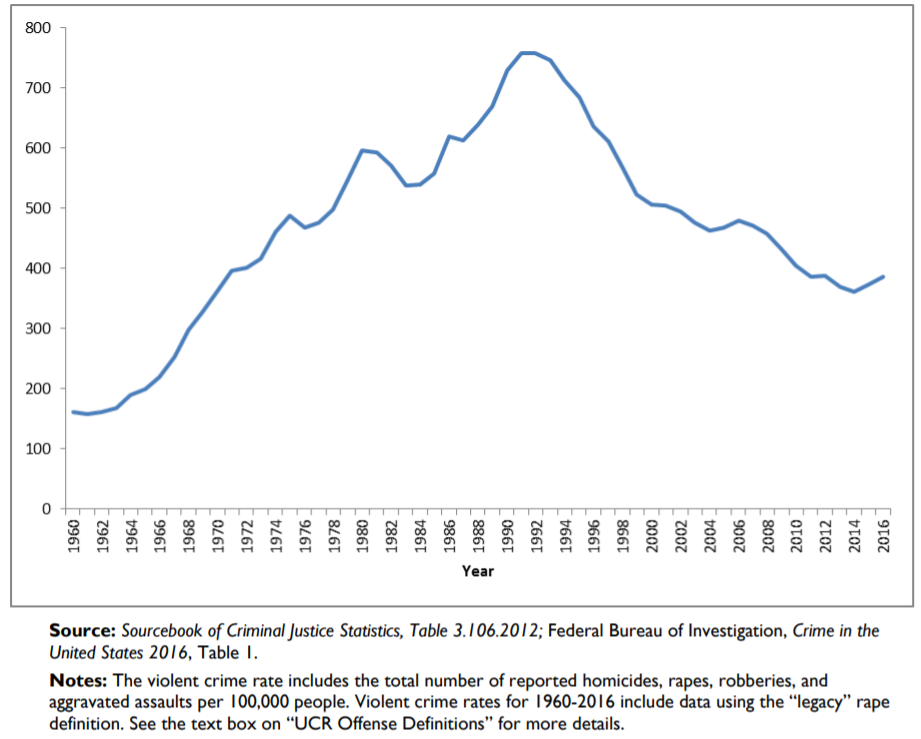

Figure 1 shows the scale of the violent crime problem Clinton faced in 1993. When the 1994 Crime Bill was being written, the rate of violent crime in the U.S. was at an all-time high post-1960 (approximately 750 violent crimes per 100,000 people per year).

Figure 1: The U.S. Violent Crime Rate (per 100,000 people) from 1960 to 2016.

The 1994 Crime Bill, the largest U.S. history in monetary terms, provided for 100,000 new police officers, $9.7 billion in funding for prisons and $6.1 billion in funding for crime prevention programs. It passed the U.S. House on a 235–195 vote on August 21, 1994 and passed the Senate August 25th on a 61 to 38 vote, including support from seven Republicans.

The 1994 Crime Bill was signed into law on September 13, 1994, two months before one of the biggest Democratic midterm election defeats in history.

Did the 1994 Crime Bill work?

The precise impact of the 1994 Crime Bill is a contentious question.

Indisputable is that the U.S. violent crime rate fell around the time the 1994 Crime Bill was passed.

But why?

Popular economist Steven Levitt, of Freakonomics fame, offered these conclusions in a 2004 research paper:

The drop in crime after 1994 is the function of (1) increases in the number of police, (2) increases in the size of the incarcerated population, (3) the waning of the crack epidemic, and (4) the legalization of abortion in the 1970s.

All four are plausible explanations, but an examination of the aggregate data casts some doubt on the importance of Levitt’s first two explanations.

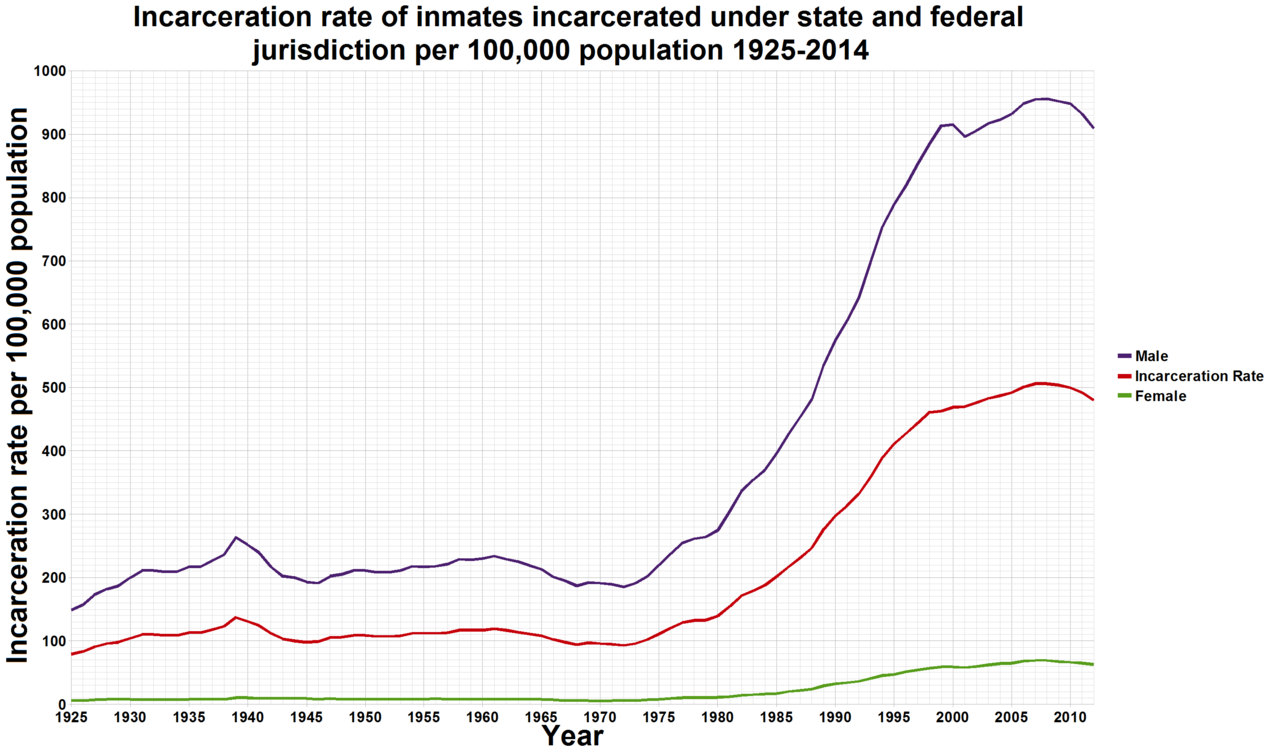

Figures 2 and 3, respectively, show the over time changes in the incarcerated population and the relative size of the U.S. police force.

Figure 2: Incarceration rate per 100,000 people from 1925 to 2014

Figure 3: Incarceration rate per 100,000 people from 1925 to 2014

A topline examination of Figures 2 and 3 suggests that the 1994 Crime Bill did little to alter the trajectory of the U.S. incarceration rate or the relative number of police on the street.

If anything, the incarceration rate and relative number of police officers on the street plateaued soon after the passage of the 1994 Crime Bill — hardly the basis for indicting Biden on growing a police state or the unnecessary incarceration of Americans. Which is not to say both aren’t happening, they just aren’t a product of the 1994 Crime Bill.

Rather, as seen in Figure 4 below, the rapid rise in incarceration rates and the number of police on the street occurred after two political milestones: (1) Richard Nixon’s 1971 declaration of a “War on Drugs,” and (2) Reagan’s Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984 (i.e., the 1984 Crime Bill).

Figure 4: Number of incarcerated Americans from 1920 to 2008

The incarceration rate for Americans rose 250 percent from 1971 to 1994 (or about 11 percent per year), but following the 1994 Crime Bill rose only 15 percent from 1995 to 2000 (or about 3 percent per year).

As for the relative number of police officers, the pivot point appears to be around the 1984 Crime Bill. From 1975 to 1984, the number of police per 100,000 residents fell 1.7 percent; however, from 1985 to 1994, the relative number of police grew 9.5 percent (or about 1 percent per year).

And how did the 1994 Crime Bill impact the relative level of police employment? It grew 7 percent from 1994 to 2001 (or about 1 percent per year).

The straightforward conclusion from this aggregate data is that the 1994 Crime Bill reinforced trends already established by Nixon’s “War on Drugs” and Reagan’s 1984 Crime Bill.

And where did Joe Biden stand on the 1984 Crime Bill? He voted for it, along with 36 other Senate Democrats (Side Note: North Carolina Republican Jesse Helms voted against the bill.)

As for the 1994 Crime Bill, the man most responsible for it, President Bill Clinton, would eventually express regret over the portions of the 1994 Crime Bill that led to an increased prison population, particularly the three strikes provision, widely considered a failed policy by policy analysts.

Biden’s criminal justice record is more than the 1994 Crime Bill

When judging Biden’s entire career on criminal justice reform, the analysis must include not only the 1994 Crime Bill but also the Comprehensive Control Act of 1984, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, and the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988 — all criminal justice bills Biden co-authored or had significant influence over its content. All together, those four bills did the following:

- allowed police to seize someone’s property without proving the person is guilty of a crime,

- created a significant sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine (which helped expand the current racial disparities in incarceration rates),

- increased prison sentences for drug possession,

- funded the building of more state prisons,

- funded the hiring of hundred of thousands of additional police officers, and,

- used grant programs to encourage more drug-related arrests— an significant escalation in the War on Drugs started under Nixon.

It is hard not to see the irony in the 2020 Biden campaign’s policy proposals on criminal justice reform:

- No one should be incarcerated for drug use alone.

- Eliminate mandatory minimums.

- Our criminal justice system must be focused on redemption and rehabilitation…Create a new $20 billion competitive grant program to spur states to shift from incarceration to prevention.

- End, once and for all, the federal crack and powder cocaine disparity.

Biden helped create the very problems he is today asking us to believe he can now fix. Forgive me, but that sounds like the Arsonist-Fireman Syndrome.

On the positive side, the U.S. experienced a dramatic decline in violent crime rates after 1994, and to the extent the 1994 Crime Bill and bills preceding it are responsible, Biden deserves some of the credit.

But is this decline the result of deterrence (e.g., stricter laws and enforcement) or incapacitation (i.e., taking criminals off the street)?

There seems to be little consensus among social scientists as to why violent crime rates have fallen since 1994.

“Despite the rich history of econometric modelling spanning over 40 years, there is arguably no consensus on whether there is a strong deterrent effect of law enforcement policies on crime activity,” write economists Maurice Bun, Richard Kelaher, Vasilis Sarafidis and Don Weatherburn, who found in their own 2016 research in Australia that “increasing the risk of apprehension and conviction is more influential in reducing crime than raising the expected severity of punishment.”

Therein lies the problem with overly harsh conclusions about Biden’s criminal justice record (or excessively laudatory ones). We generally can’t assign levels of credit or blame on extremely complex social processes.

On the first-order effects (action ⟹ consequences), there is modest evidence that the “tough-on-crime” laws from 1984 to the present helped lower violent crime rates, though exactly how those laws lowered crimes rates remains debatable. Was it deterrence or incapacitation? Probably both.

But particularly with incapacitation, the higher-order effects (consequences ⟹ consequences, i.e., “consequences have their own consequences”) may have had contradictory effects for the communities where their young men have been disproportionately incarcerated. On the one hand, these communities are demonstrably safer today than they were 30 years ago — that has distinct economic benefits. At the same time, generations of young men who could have been adding to the economic base of their communities are, instead, economically marginalized (often permanently) by the broader society.

Over his long legislative history, Joe Biden has addressed urban crime the way the U.S. military addresses its urban-based enemies — destroy the village in order to save it.

Yes, crime is down, but at what cost? Were there better ways to reduce crime without creating permanently distressed communities? [Yes, there were.]

If Biden wants some of the credit for the unprecedented decline in U.S. violent crime since 1994, he is more than justified. He cut his political teeth during Nixon’s “War on Drugs” and achieved significant senatorial power when the Reagan Revolution was at its apex.

Biden’s criminal justice legacy is the product of those two prominent political forces. He doesn’t run from this reality. In fact, he embraces it.

However, at the same time, he must own the consequences of those policies used to achieve this landmark drop in crime, for they created the context within which deaths like George Floyd’s are sadly inevitable.

Too many of our urban police forces act more like occupying armies than as servants to a public they take an oath to protect. That reality is the dark side of the “tough-on-crime” policies politicians like Biden enacted.

Joe Biden needs to own responsibility for that result too.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: kroeger98@yahoo.com

Or tweet me at: @KRobertKroeger1

APPENDIX

I find this graphic distressing. It shows the incarceration rates around the world if every U.S. state were a country. For example, Hawaii has an incarceration rate similar to Cuba’s!

Figure A1: World Incarceration Rates If Every U.S. State Were a Country, 2016, per 100,000 people (Source: States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2018, PrisonPolicy.org)

Figure A2: World Incarceration Rates If Every U.S. State Were a Country, 2016, per 100,000 people (Source: States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2018, PrisonPolicy.org)