By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, May 25, 2020)

The analysis of stool samples is a vital screening method for medical conditions ranging from colorectal cancer, hookworm, rotaviruses, and lactose intolerance.

It seems only logical that the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) could also be detected in stool samples.

In Paris, France, researchers monitored genome unit levels of SARS-CoV-2 in waste waters between March 5 to April 23 to determine if variations over time tracked closely with COVID-19 cases observed in the Paris-area.

They did.

Though it has not been peer-reviewed, the researchers posted their preliminary study on May 6th:

“The viral genomes could be detected before the beginning of the exponential growth of the epidemic. As importantly, a marked decrease in the quantities of genomes units was observed concomitantly with the reduction in the number of new COVID-19 cases which was an expected consequence of the lockdown. As a conclusion, this work suggests that a quantitative monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 genomes in waste waters should bring important and additional information for an improved survey of SARS-CoV-2 circulation at the local or regional scale.”

If your reaction to this research is — “Aren’t we already doing this for other diseases and public health issues?” — you would be correct.

This type of real-time health monitoring method dates back at least to the 1990s when environmental scientists began to observe the presence of pharmaceuticals in local waste waters (including illicit drugs), according to Christian G. Daughton, a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency scientist.

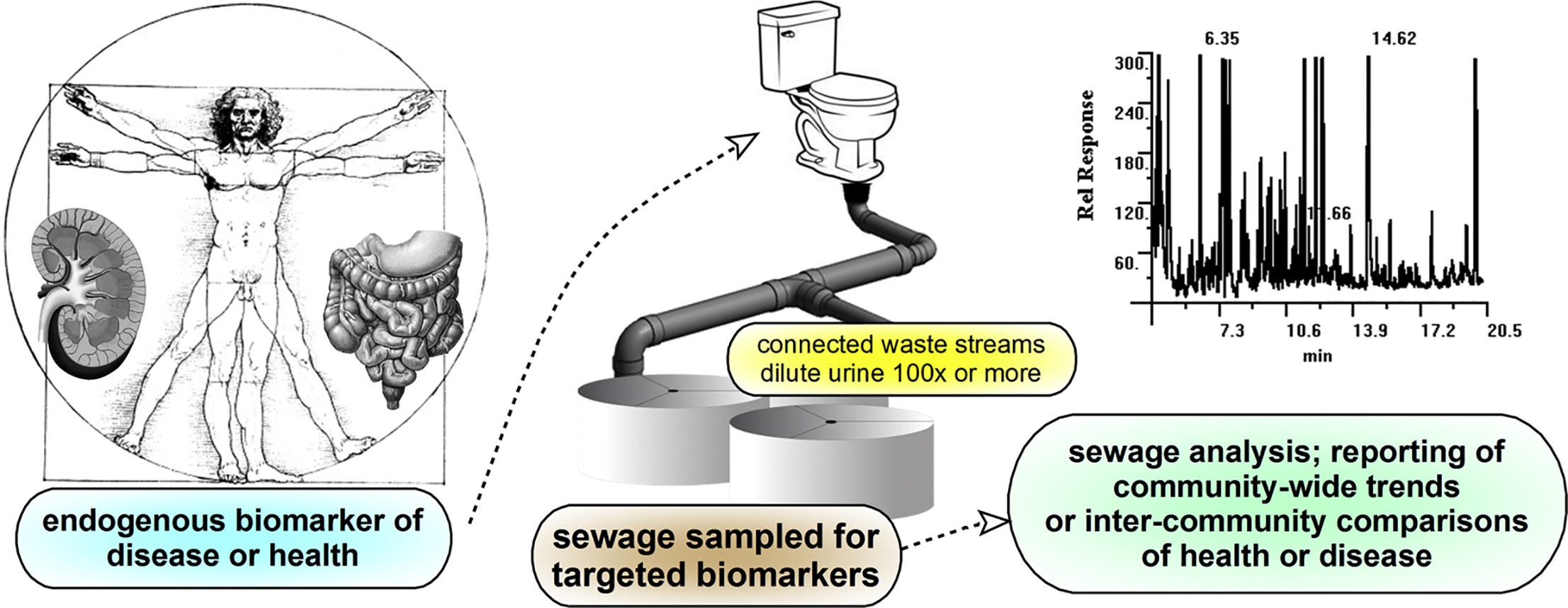

First proposed in 2012, Daughton has been developing a bioanalytic method called Sewage Chemical-Information Mining (SCIM) in which sewage is monitored for natural and anthropogenic chemicals produced by everyday actions, activities and behaviors of humans. One variation of this method — BioSCIM — is described by Daughton as “an approach roughly analogous to a hypothetical community-wide collective clinical urinalysis, or to a hypothetical en masse human biomonitoring program.”

When implemented, a BioSCIM program will be able to track community-wide health trends on a continuous basis.

But Daughton is far from alone in proposing this type of sewage-based health monitoring.

“If you are at the mouth of a wastewater treatment plant, you essentially can observe all the chemistry that is being used in a city,” says Rolf Halden, director of the Center for Environmental Health Engineering at Arizona State University’s Biodesign Institute. “You can measure the metabolites that have migrated through a human body. You can look at medications that are being taken. In essence, you’re at a place where you can observe human health in real time.”

Though privacy advocates may have reservations about the government or corporate entities monitoring something so private as our bodily wastes (the ACLU has not returned my phone call on this issue), researchers say the way sewage-based monitoring systems are designed makes it impossible to link individuals — whose genetic identifiers are mixed amidst the metabolites of interest — to specific pharmaceuticals, behavioral by-products, health conditions, and/or diseases.

However, they could tell you what cities and neighborhoods index high on these things, and it is not hard to imagine law enforcement authorities finding a reason to plug into this information. Or national intelligence agencies, perhaps?

Think about it.

Given that SCIM and other community-level biomonitoring techniques are fairly well established, it is astonishing that there is no systematic effort by U.S. cities, counties, states or the national government to use this valid, reliable, and non-intrusive technique for tracking the spread of the coronavirus.

We know the widely reported COVID-19 case numbers in the U.S. and worldwide are inaccurate.

“Inadequate knowledge about the extent of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic challenges public health response and planning,” according to USC public health researchers who recently released an April study on the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies among adults in Los Angeles County, California. “Most reports of confirmed cases rely on polymerase chain reaction–based testing of symptomatic patients. These estimates of confirmed cases miss individuals who have recovered from infection,with mild or no symptoms, and individuals with symptoms who have not been tested due to limited availability of tests.”

“The number of confirmed COVID-19 cases is a poor proxy for the extent of infection in the community,” one of the study’s researchers, Neeraj Sood, told the USC online news site.

For five months now, on a daily basis, our governments and worldwide news agencies have been reporting inaccurate numbers that do not give an unbiased picture of the coronavirus pandemic. They are bean-counting and they don’t know where all the beans are or which ones to count.

It did not need to be this way. We should have been analyzing our pee and poop from the beginning.

(There was no nice way to say that.)

- K.R.K.

Send comments and stool samples to: kroeger98@yahoo.com or by tweet to: @KRobertKroeger1