By Kent R. Kroeger (Source NuQum.com, May 21, 2020)

Disclaimer: Though I address significant legal issues in this article, I am not a lawyer, only a concerned citizen and writer that places an extremely high value on our First Amendment rights — which I believe are under siege.

Is it illegal for a U.S. presidential campaign to obtain from a foreign source, by purchase or gift, derogatory information about an opponent?

If you believe U.S. campaign finance law makes it clear that such behavior is illegal, you didn’t read Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller, III’s Report On The Investigation Into Russian Interference In The 2016 Presidential Election.

But, before addressing this question, why am I even asking it? Aren’t we done with the Trump-Russia conspiracy theory? I’m as sick of the story as anybody. Let us move on.

Unfortunately, paraphrasing Michael Corleone in The Godfather: Part III, the Trump-Russia story keeps pulling us back in.

What draws us back in this time? For a brief moment last week, Obamagate replaced the coronavirus pandemic in the headlines.

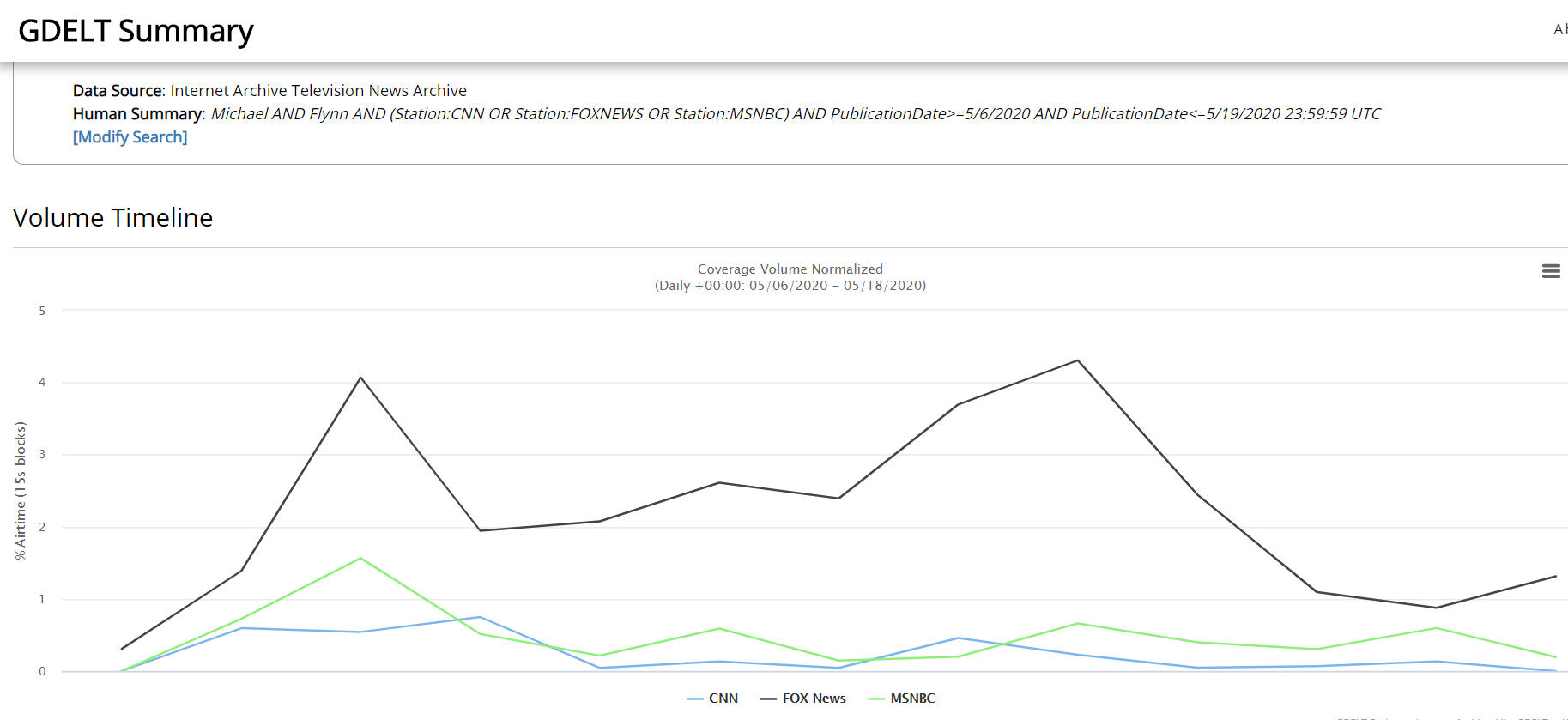

If you somehow missed the Obamagate story — and if you get your news from CNN or MSNBC, I’m not surprised (see the Appendix for a graph of cable news network coverage of the story) — let me give you a brief overview:

In early January 2017, as the FBI was about to end its counter-intelligence investigation into General Michael Flynn’s relationship with Russia based on finding no improper activities, FBI Director James Comey decided to keep it going long enough to interview Gen. Flynn regarding the contents of a December 2016 meeting between Flynn and Russian ambassador Sergey Kislyak. In that FBI interview, conducted under oath at the White House, Flynn provided false information regarding the Kislyak meeting, and Flynn subsequently pleaded guilty to perjury (twice) with respect to his FBI interview.

So how did that become labelled as Obamagate?

Despite promising my therapist I would stop quoting comedian Jimmy Dore when discussing actual news, I’ve found a work-around. Here is comedian Joe Rogan’s retelling of Jimmy Dore’s summary of Obamagate:

“(Obama) was using the FBI to spy on Trump, and when it turned out that all that Russia-collusion stuff didn’t happen — and the Obama administration knew it didn’t happen —they still tried to turn it into something that it wasn’t.”

As a result, according to Trump allies, Gen. Flynn became one of the fall guys for a failed conspiracy theory originally concocted by the Hillary Clinton campaign, the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and Steele Dossier author Christopher Steele, but ultimately passed on to the Obama administration.

Whatever one’s partisan biases, indisputable is this fact: The Mueller investigation into a possible Trump-Russia conspiracy resulted in zero conspiracy-related indictments. All indictments generated by the investigation were process crimes (i.e., perjury) or ancillary crimes unrelated to Trump and Russia (e.g. Paul Manafort’s illegal financial activities).

Whether you agree or disagree with what Mueller’s team decided is not the point of this article. I will not re-litigate Russiagate. People have made up their minds and I’m fine with that.

But what I believe to be the central legal question of Russiagate — the procurement of opposition research (information) from foreign sources — remains unanswered.

Or is it?

The primary finding of the Mueller Report was that no compelling evidence exists suggesting the 2016 Trump campaign directly or indirectly conspired with any Russian entity to influence the 2016 election outcome.

One could argue (and I do) that the entire Russiagate controversy pivots on the events related to the acquisition of derogatory information regarding Hillary Clinton and the Democratic Party (i.e., deleted and hacked emails).

With respect to the hacked emails, we now know from recently released closed congressional committee interviews that the evidence linking the Russians to the DNC and Podesta email hacks is less than conclusive. I will remind readers, however, that the National Security Agency (NSA) — the U.S. intelligence agency of record on cyber-intelligence issues — concluded with “moderate” confidence that the Russians were responsible for the DNC/Podesta email hacks. But that is a topic for another day. [Spoiler alert: I still think Russia-aligned actors hacked, at a minimum, the Podesta emails.]

Apart from the fact that the U.S. news media selects its stories based more on how well they serve a pre-selected narrative (“Trump is bad”) than on a story’s basis in fact, Russiagate brings to the fore the question of whether foreign-sourced information is allowable in a U.S. presidential election.

If the U.S. Constitution still matters, the answer must be ‘yes.’

Still, we must ask, is the manner in which this information obtained pertinent?

Of course it is. No U.S. presidential campaign is allowed to steal the emails or private communications of an opposition campaign. If Person A steals the emails of Person B and gifts them to Person C, Persons A and C are complicit in a prosecutable crime.

But that is not what happened in 2016, according to the Mueller Report and the publicly known facts.

The evidence Trump’s adversaries cite to demonstrate his conspiratorial activities with the Russians comes down to these seven events:

(1) Donald Trump Jr.’s Trump Tower meeting with Russian lawyer Natalia Veselnitskaya over possible “dirt” against Hillary Clinton.

(2) Trump associate Roger Stone’s interactions with Wikileaks prior to the release of the DNC/Podesta stolen emails (yes, there were stolen).

(3) Trump campaign adviser George Papadopoulos’ boast to an Australian foreign diplomat that he had Russian contacts with knowledge about Hillary Clinton’s 30,000+ deleted emails.

(4) Donald Trump’s own campaign stump speeches where he appeals to the Russians to release Hillary Clinton’s 30,000+ deleted emails.

(5) General Michael Flynn’s private conversations with Russian ambassador Sergey Kislyak in December 2016.

(6) Former Trump campaign manager, Paul Manafort, sharing internal polling data with Konstantin Kilimnik, a Russian national with ties to Russian intelligence, according to the Mueller Report (Vol. I, p. 6).

(7) The Trump Organization’s pursuit of a Trump Tower project in Moscow concurrent with the 2016 presidential campaign.

Apart from process crimes (e.g., perjury) related to the FBI’s investigation of these events, not one of them warranted a criminal indictment by Robert Mueller’s special investigation.

Why didn’t Mueller’s team find at least one prosecutable conspiracy crime during their three-year investigation?

The most defensible answer is that such crimes didn’t exist.

Most supportive of the Trump campaign’s innocence is that none of the seven events listed above are in dispute by the participants, including the substance within those events.

In the Mueller Report’s own words (Vol. I, pp. 183–184):

“Several areas of the Office’s investigation involved efforts or offers by foreign nationals to provide negative information about candidate Clinton to the Trump Campaign or to distribute that information to the public, to the anticipated benefit of the Campaign.

The Office determined that the evidence was not sufficient to charge either incident as a criminal violation.”

However, by saying the “evidence was not sufficient” for an indictment, many of Trump’s critics are left howling at Mueller’s timidity. What more evidence did he need?

Though not sufficiently elucidated, the Mueller Report lays out the reasons for not pursuing a campaign finance violation against the Trump campaign, despite legal interpretations of campaign finance law broadly supporting bans on foreign-sourced “things of value” (Vol I., p. 187):

“These authorities would support the view that candidate-related opposition research given to a campaign for the purpose of influencing an election could constitute a contribution to which the foreign-source ban could apply.

A campaign can be assisted not only by the provision of funds, but also by the provision of derogatory information about an opponent. Political campaigns frequently conduct and pay for opposition research. A foreign entity that engaged in such research and provided resulting information to a campaign could exert a greater effect on an election, and a greater tendency to ingratiate the donor to the candidate, than a gift of money or tangible things of value.

At the same time, no judicial decision has treated the voluntary provision of uncompensated opposition research or similar information as a thing of value that could amount to a contribution under campaign-finance law. Such an interpretation could have implications beyond the foreign-source ban, see 52 U.S.C. § 30116(a) (imposing monetary limits on campaign contributions), and raise First Amendment questions. Those questions could be especially difficult where the information consisted simply of the recounting of historically accurate facts. It is uncertain how courts would resolve those issues.” [Bolded emphasis mine]

Buried in a 400+ page report, deserving only one single sentence, Mueller’s team acknowledges that the criminalization of the “voluntary provision of uncompensated opposition research…raises First Amendment questions.”

No kidding. [Pardon my sarcasm, but the central issue within the entire Russiagate brouhaha — the seeking of foreign-sourced derogatory information about a political opponent — was addressed in ONE sentence on page 187.]

I recognize that the average national journalist today doesn’t care about protecting First Amendment rights as their career doesn’t depend on protecting those rights. In fact, most seem happy to drop kick the First Amendment into the Potomac.

My evidence? Besides the fact I can’t name one mainstream U.S. journalist that questions why Wikileaks publisher Julian Assange sits in a British prison for publishing U.S. national security secrets (or abuses, depending on your point-of-view), I cannot find an example of a major U.S. news outlet having discussed with any depth Russiagate’s First Amendment implications.

Not a single one. Even Fox News and The Wall Street Journal have largely neglected this crucial aspect of the Russiagate story (The Wall Street Journal’s Kimberely Strassel being a notable exception).

How is that possible? Surely someone at the New York Times or Washington Post cares about First Amendment rights?

In contrast, the other side of the argument seems more than willing to piss on our constitutional protections if it means bringing down Donald Trump.

Nothing demonstrates the moral (and legal) low ground of Russiagateniks better than New York Representative Hakeem Jeffries admitting during Trump’s U.S. Senate impeachment trial that “payment” for foreign-sourced opposition research like the Steele Dossier is totally kosher.

If hypocrisy were an Olympic gymnastic event, Jeffries would get all 10s.

Watch and enjoy:

Asked whether, under the Dems' impeachment standard, the Clinton campaign's solicitation of the Steele dossier would be considered foreign interference, illegal, or impeachable, @RepJeffries says no — because the Steele dossier "was purchased." pic.twitter.com/SbEKFGNwM4

— Aaron Maté (@aaronjmate) January 30, 2020

What Rep. Jeffries is trying to sell you is a diversionary truckload of legal nonsense. The distinction between paying for foreign-sourced opposition research and receiving it for free (for example, in the process of doing research) is most likely an artificial one, though admittedly untested in the U.S. courts (according to the Mueller Report).

That should have changed with Russiagate and the Mueller investigation, but it didn’t. Why not?

Because every D.C. lawyer knows the First Amendment allows the use of foreign-based sources — paid or unpaid — to collect information, derogatory or otherwise, on American political actors. It’s called journalism. It’s free speech, as in, protected by our Constitution. Mueller’s team knew challenging that right in a U.S. court would have had a flying pig’s chance of success.

Unfortunately, U.S. campaign finance law doesn’t directly address this issue either. Here is the statutory prohibition on foreign-sourced campaign contributions based on Title 52 USC 30121: Contributions and donations by foreign nationals:

(a) Prohibition

It shall be unlawful for (1) a foreign national, directly or indirectly, to make:

(A) a contribution or donation of money or other thing of value, or to make an express or implied promise to make a contribution or donation, in connection with a Federal, State, or local election;

(B) a contribution or donation to a committee of a political party; or (C) an expenditure, independent expenditure, or disbursement for an electioneering communication (within the meaning of section 30104(f)(3) of this title); or

(2) a person to solicit, accept, or receive a contribution or donation described in subparagraph (A) or (B) of paragraph (1) from a foreign national.

(b) The term “foreign national” means

(1) a foreign principal, as such term is defined by section 611(b) of title 22, except that the term “foreign national” shall not include any individual who is a citizen of the United States; or

(2) an individual who is not a citizen of the United States or a national of the United States (as defined in section 1101(a)(22) of title 8) and who is not lawfully admitted for permanent residence, as defined by section 1101(a)(20) of title 8.

At the risk of over-simplification, Russiagate hinged on the definition of ‘other thing of value’ (in line a-1A): Wouldn’t “dirt” on Clinton qualify as something of value, thereby making its free acquisition from a foreign national an illegal campaign contribution by the Trump acquisition?

First, the Trump campaign never received any “dirt” on Clinton, so that is their first line of defense (though, in the case of the DNC/Podesta/Clinton emails, an attempt to procure stolen goods is potentially a criminal offense). Second, even if they had, the Mueller team conjectured (wrongly) that the Trump campaign’s legal jeopardy might be minimized if “the information consisted simply of the recounting of historically accurate facts.”

The U.S. legal history on defamation and First Amendment rights is too extensive and complex to retrace here, but suffice it to say the case law leans in favor of free speech and the press and generally forgives unintentional factual mistakes.

“Error is inevitable in any free debate and to place liability upon that score, and especially to place on the speaker the burden of proving truth, would introduce self-censorship and stifle the free expression which the First Amendment protects,” according to a 2012 Congressional Research Service analysis of U.S. Supreme Court First Amendment cases.

Even the Steele Dossier, despite having more in common with fiction writing than journalism, would likely be constitutionally protected.

Finally, adding to the protection of the Trump campaign’s 2016 activities (and the Clinton campaign activities also) is the Overbreadth Doctrine — a legal principle that says a law is unconstitutional if it prohibits more protected speech or activity than is necessary to achieve a compelling government interest. The excessive intrusion on First Amendment rights, beyond what the government had a compelling interest to restrict, renders the law unconstitutional.

One common cause of such an intrusion is a statute that using overly broad definitions and language. I’m not a lawyer, but the campaign finance statute’s use of concepts such as “other thing of value” would be ripe for an Overbreadth Doctrine challenge.

Final Thoughts

Nothing speaks to the self-inflicted lunacy of the political establishment Left than their willingness to embrace the Steele Dossier — an anti-Trump hit piece of mostly secondhand hearsay, possibly from Russian intelligence operatives (or, as they are frequently called in the U.S. media,“Kremlin insiders”).

And do you think anybody in the U.S. media went to the effort to independently verify the information in the Steele Dossier? Journalist Bob Woodward tried and in his words: “I could not verify what was in the Dossier.”

And that is pretty much where we stand today. The Mueller-led investigation into Russiagate punted on potentially the most consequential legal aspect of the story: Is it legal for a political campaign (or anyone, for that matter, as we are all protected by the First Amendment, not just journalists) to acquire from a foreign-based source any derogatory information about another political campaign.

The Mueller team plainly had an educated hunch that a court’s answer would be “yes, it is legal,” but decided to bury that important insight on page 187 of their report.

Thank God I didn’t fall asleep until page 192.

- K.R.K.

Send comments and grand jury subpoenas to: kroeger98@yahoo.com, or tweet me at: @KRobertKroeger1

APPENDIX: Cable News Coverage of the Michael Flynn Story (5/6/20 to 5/19/20)

For the most part, only Fox News has consistently covered the Michael Flynn story over the past two weeks. Does that make it fake news? Discuss.