By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; December 12, 2018)

Nothing brings more hate mail to my inbox than articles I write about climate change.

It’s the new Obamacare. Not open for debate. It’s the third rail of Democratic Party politics. Any criticism, no matter how minor, of the tactics or policy proposals generated by the activist community is unacceptable. And you will be called an uneducated, bucktoothed climate change denier — which was one of the more civil comments I received concerning my article on France’sYellow Vest protests.

What is it about climate change?

I write about Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez being the Democrats’ most charismatic and intuitive politician and compare her to John F. Kennedy…not a peep.

I declare the elections of Rashida Tlaib and Illhan Omar to the U.S House the most important election outcomes in 2018…not one hostile comment.

I call out the faux-outrage over Megyn Kelly’s ‘black face’ comment and rue her firing by NBC…and, again, nada.

But I suggest carbon taxes that disproportionately hurt low-income households are politically nonviable, and that climate change activists that drive BMWs and regularly vacation in the Maldives are hypocrites and probably frauds…and boom, here comes Mother Mary Joseph Rogers, and I get annihilated.

‘Your ignorance of the science shines through in every dim-witted, ill-informed sentence you burden on your readers,” wrote one of my more loyal readers.

“Blood is already on the hands of people like you who stand in the way of climate change justice,” wrote another reader. [Is there a word more chronically overused and misused than ‘justice?’ Climate change justice? What does that even mean? The word ‘justice’ has become a verbal tic for the progressive left. Similar to how teenagers say ‘like’ all the time. We need a new word. I nominate ‘fairness.’]

“You’re a f**king denier.” was the punctuated end to another email response I received.

Nice.

Unfortunately, for those critics at least, it is not possible to find one sentence I’ve ever written on climate change where I’ve denied its reality, its human origins, or the urgency of its mitigation.

Not once.

If anything, my analyses of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and International Energy Agency (IEA) public use data match closely to the forecasts made by mainstream climate scientists.

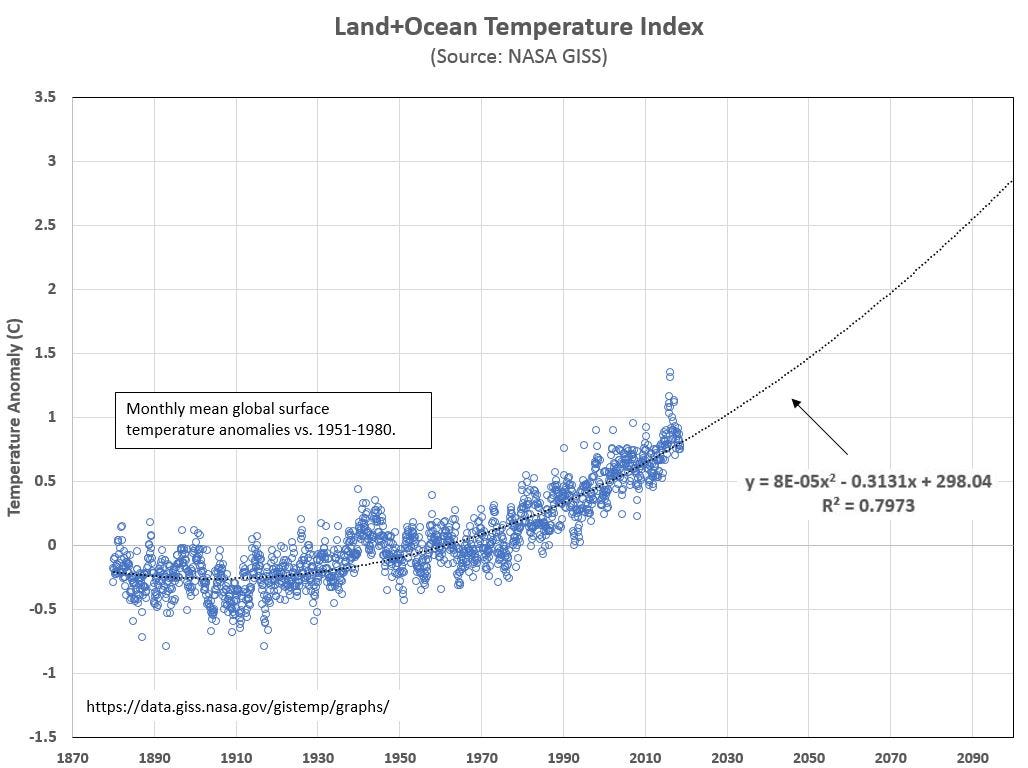

Case in point, my simple-model forecast for global temperatures (land and ocean) through 2100 is not optimistic. Using an non-dynamic (atheoretic) model where I assume the process generating past temperature anomalies will continue into the future, I forecast the world will pass the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) ceiling target of 1.5° C warming around 2050 and reach 3.0° C around 2100.

Figure 1. Land and ocean temperature index

It is impossible to look at the historical data in Figure 1 and not see a positive trend in global temperatures. Some global warming skeptics focus on the brief period between 1930 and 1945 where global temperatures increased more rapidly (almost 1.0° C in just 15 years) than they are now. Clearly, that represents recent evidence that natural factors (non-human related) do affect global temperatures in a systematic way. But the same evidence also demonstrates the temporary nature of the 1930–45 warming period and how it returned to ‘normal’ from 1950 to the mid 1970s.

And then global temperatures started to increase and have continued to do so up to the present. The infamous ‘pause’ between 1998 and 2012 was just that…a temporary pause.

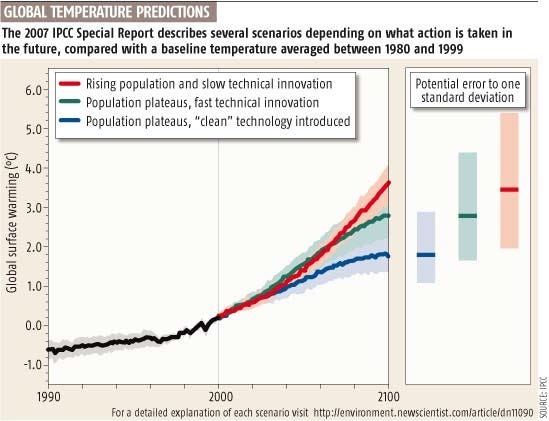

Feel free to question the simplicity of my forecast model, but I do gain some satisfaction in knowing that my prediction of 3.0° C warming by 2100 tracks closely with much more sophisticated models, including ones published in recent IPCC reports (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Global Temperature Predictions

I thought this article was about tropical cyclones and hurricanes?

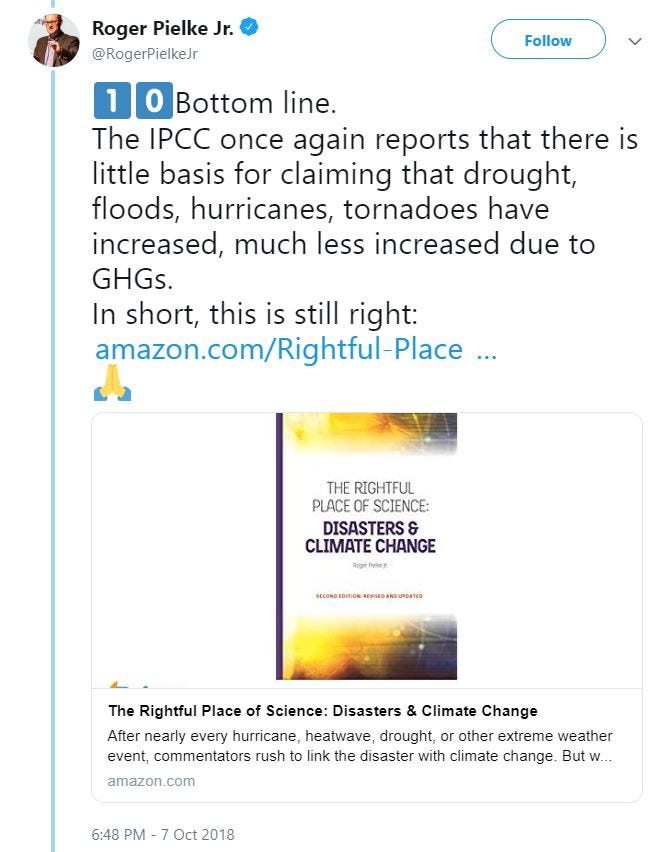

Critics of the recent IPCC report issued this fall noted that its authors admitted a degree of uncertainty in the conclusion that tropical cyclones (tropical storms, typhoons and hurricanes) have increased in frequency or intensity (energy) due to global warming.

Tweeting out at the release of the IPCC report, University of Colorado climatologist Roger Pielke, Jr. observed:

Pielke and his colleagues also recently released updated research on trends in hurricane damage in which they concluded: “Consistent with observed trends in the frequency and intensity of hurricane landfalls along the continental United States since 1900, the updated normalized loss estimates also show no trend.”

One of the problems with IPCC reports (and the recent U.S. government report on climate change) is that the reports’ executive summaries written for policymakers tend to sound more dire than the actual science detailed in these same reports.

That is the unfortunate outcome when science meets politicians.

Regardless, I am a bit puzzled why there is so much hesitation within the scientific community to declare that we are seeing a definite increase in the frequency and intensity of tropical cyclones (at least in the Atlantic basin). I realize, unlike me, climatologists such as Pielke have actual credentials. So when Pielke and his colleagues say there are no trends in hurricane damage, I take it seriously.

But I don’t see how anyone can deny that there are more frequent and powerful hurricanes in the Atlantic basin over the past thirty years.

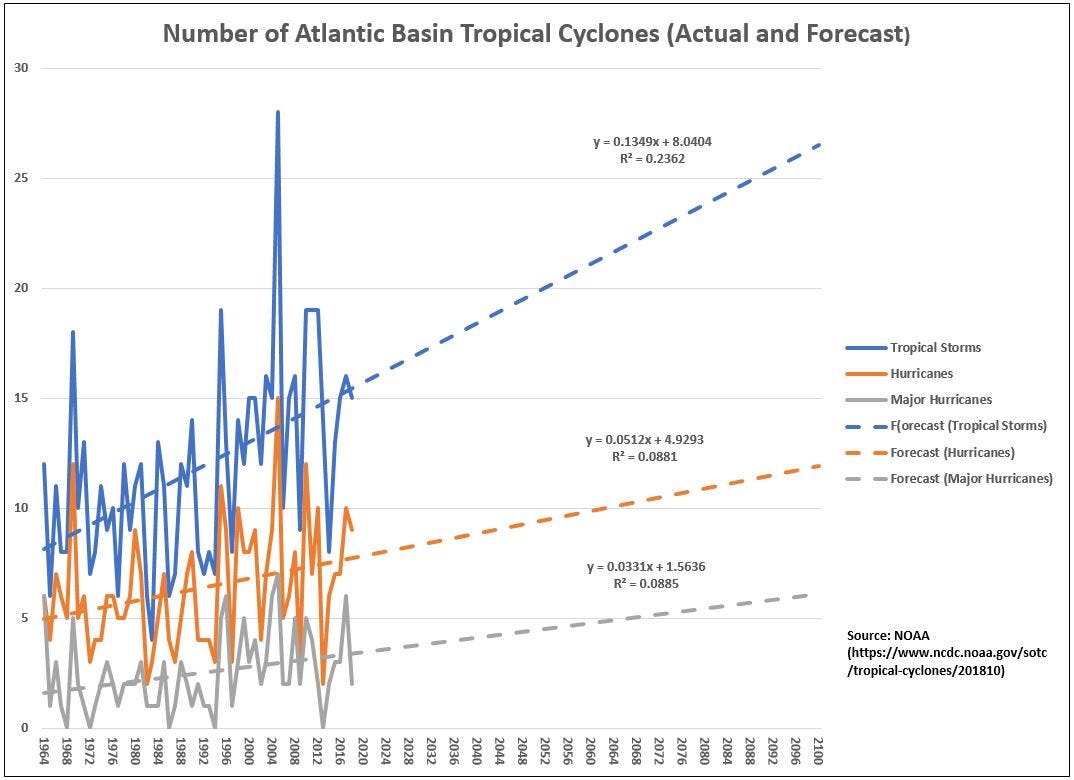

Figure 3 shows National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) historical data on tropical cyclones in the Atlantic basin. It should also be noted that these trends are not significantly affected by the date I chose to start the series. I use 1964 as the starting date because that marks the beginning of NASA’s Nimbus weather satellite program in which the U.S. maintained continuous satellite coverage of weather patterns in the north Atlantic. I could have chosen 1960, or 1950, or 1857. It didn’t matter. The positive trends were consistent across starting points.

This significance in the increase in the frequencies of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes is not marginal. The upward trends are strong, particularly for the number of tropical storms. By 2100, the Atlantic basin will experience around 26 tropical storms annually, compared to 15 today. The number of hurricanes will increase from about 8 per year now to 12 by the end of the century. Likewise, major storms will increase from about 3 to almost 6 annually by 2100.

Three more major storms in the Atlantic each year will be one of the tangible consequences of global warming.

So what should we do?

If we give Nancy Pelosi and Frank Pallone control of $4 trillion more dollars in the next 20 years, I guarantee most of it will get funneled to big, Democrat-aligned money donors. I guarantee it. And only then will the Republicans find Jesus on climate change so they too can get their friends in on the financial windfall.

What will be the most cost-effective way to address climate change? A prosperous, free market economy empowering people with good, private sector jobs to make the decisions necessary to meet the challenges of climate change. It will be household-level decisions that determine the extent to which climate change negatively impacts the U.S. and the world.

For example,

- People need to start moving away from vulnerable coastlines, lowland inlets, riverbanks and areas vulnerable to wild fires. As we saw sadly in California, there is no fire-retardant building material that can always stop a massive wild fire from destroying a home. And low-income households in such areas may need financial help in that regard (so adding more taxes to their life does not sound like an idea that moves that all forward).

- Insurance companies need to increasingly factor in the risks associated with climate change. That will be a powerful motivator for decisive action at a microeconomic-level.

- Governments need to adjust zoning laws and building codes. Some graduate student should do a case study on how Oregon effectively limits housing and commercial development along its coastline.

- Government debt— at all levels — needs to be reduced to help spur private investments in the new technologies that will transform the world’s energy economy (electric cars, battery storage, carbon capture and sequestration, smart grid energy systems, etc.).

- To avoid the crucial mistakes Germany has made in moving too fast on renewable energy, the U.S. needs to increase (not decrease) the role of natural gas will play in the next 20 to 30 years as a transitional energy source as we wait for battery storage technologies improve.

- If current levels are maintained in the U.S., nuclear power will provide critical power capacity to keep us on track to have near-100 percent non-fossil fuel electricity generation by 2050. Even so, we may end up envying those countries that have maintained an expertise in nuclear power plant construction as their transition to zero-emissions may occur faster and with lower average costs to consumers. Don’t be surprised if Pakistani, Indian or Chinese companies end up re-building the U.S. nuclear power industry in the latter half of this century. I’m sure they will be more than happy to build such plants in the U.S., for the right price.

What not to do?

- Stop trying to further empower politicians and bureaucrats by giving them more of our money. They already have enough money at their disposal to address climate change. They just need better priorities (and they can start by ending a few of our current war entanglements). Besides, what major national problem has the U.S. government ever solved in the past thirty years? We are better off leaving Uncle Sam with a minor support role and let the private sector drive the transition to 100-percent renewable energy.

- Don’t build out renewable energy capacities too soon, as a lot of that technology will be out-of-date just as it comes online. Furthermore, if too much of the build-out is done before critical battery storage technologies have advanced far enough to address renewable energy’s intermittency problem, it will increase energy costs, disproportionately hurting low- and middle-income households.

- Stop using climate change as a partisan wedge issue. It is hurting the ability of the U.S. to address climate change in a long-term, effective manner. The consequences of this approach are clear: U.S. climate change policy yo-yo’s from one administration to the next. The Democrats take charge and implement their climate initiatives, only to have the Republicans reverse them once they take control. And, no, the Democrats are not on the cusp of a permanent electoral majority that will prevent the Republicans from regaining control of the government. A new generation of climate change activists therefore are needed that, on the one hand, are not dedicated to punishing corporate America (particularly the big oil and gas companies) and, on the other hand, are not bought and paid for by that same corporate America. They will need to be what was once called a non-partisan, independent policy advocate. They used to roam freely and in relatively large numbers around Washington, D.C. Now, they are all but extinct. For climate change to be confronted rationally, that has to change.

So, there you go. I solved the climate change problem just in time to catch the end of another Glenn Beck history lecture on Woodrow Wilson. It is amazing how much Glenn can come up with about our 28th president.

-K.R.K.