By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, September 12,2017)

{ Feel free to send any comments about this essay to: kkroeger@nuqum.com or kentkroeger3@gmail.com}

Along with death and taxes, we should add this: Houston floods and Florida gets hit by hurricanes.

Journalist Daphne Thomspson understands what frequently happens when you build a large metropolitan area on a Texas bayou: “Founded in 1836, where the Buffalo Bayou met White Oak Bayou, Houston has faced many floods,” she writes.

As Thompson further notes, “In 1929, the Buffalo and White Oak Bayous both left their banks after a foot of rain fell. Downtown (Houston) suffered massive damage. Property damage was estimated at $1.4 million.”

This is a historical reality for Houstonites; but, in covering Hurricane Harvey, the national media has created an impression that the flooding caused by Harvey is without precedent.

Yes, Hurricane Harvey dumped more rain on the Houston area than any other storm in the city’s modern history. But here is just the short list of major Houston floods from the past century.

- December 6–9, 1935 – A massive flood kills 8 people.

- September 11, 1961 – Hurricane Carla.

- August 18, 1983 – Hurricane Alicia.

- October 15-19, 1994 – Hurricane Rose brings with it The Great Flood of ’94 as it stalled over north Houston for a week and killing 22 people; it dumped over 30 inches of rain in north Houston and still holds the record for the highest flood levels for the San Jacinto basin.

- June 5 – June 9, 2001 – Tropical Storm Allison floods Houston’s Central Business District and was called a ‘500-year event.’

- June 19, 2006 – Major flooding in Southeast Houston.

- September 13, 2008 – Hurricane Ike.

- May 25 – May 26, 2015 – Flooding from storms is called “historic” and impacts most of the city.

- April 18, 2016 – This flood affects nine counties in the Houston area.

- August 2017 – Hurricane Harvey dumps more rain over a week than any storm in Houston’s history.

Houston is built in a low-land area subject to hurricanes, slow-moving storm systems and frequent flooding. Is global warming the cause of Houston’s extreme flooding from Hurricane Harvey? Probably yes but not necessarily.

Yes, the amount of rain deposited by Hurricane Harvey is historic and I wouldn’t want to be on the side arguing against climate change’s role — but Houston is always flooding!

To think we can distinguish the source of Houston’s flooding between its inherent geographic vulnerability and the effects of global warming is analytic dreamweaving.

Houston is not a good place to put a major metropolitan area — but that is what the Texans have done.

Hurricane Irma, likewise, while impressive in size and intensity, was not the most powerful hurricane to ever hit the U.S. or even Florida.

That doesn’t diminish the tragedy or disprove the role that climate change may have had in the scope of Irma’s damage. Anyone that’s lived in Miami for the past few decades will tell you that high-tide flooding around downtown Miami is the new normal.

“The water is here. It’s not that I’m talking about some sci-fi movie here. No. I live it. I see it, it’s tangible,” long-time Miami resident Valerie Navarrete recently told a Yale researcher who studies rising sea levels.

According to Navarrete, her garage now floods about once every other month.

That is what rising sea levels will do. Did global warming cause it? The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimates sea levels will continue to rise at a rate of about one-eighth of an inch per year. If that doesn’t sound like a lot, its because it is not. Yet, Miami residents will tell you that aggregating those small annual sea level changes over decades and you can start to see and feel it, particularly during high tides.

CLIMATE REALISM SUGGESTS ADAPTING TO CLIMATE CHANGE IS OUR MOST EFFECTIVE POLICY TOOL

The recent experiences in Florida and Texas bring to the fore our nation’s need to reconcile the realities of global warming (which includes rising sea levels and increased storm intensities) with the urban planning decisions made many decades before today.

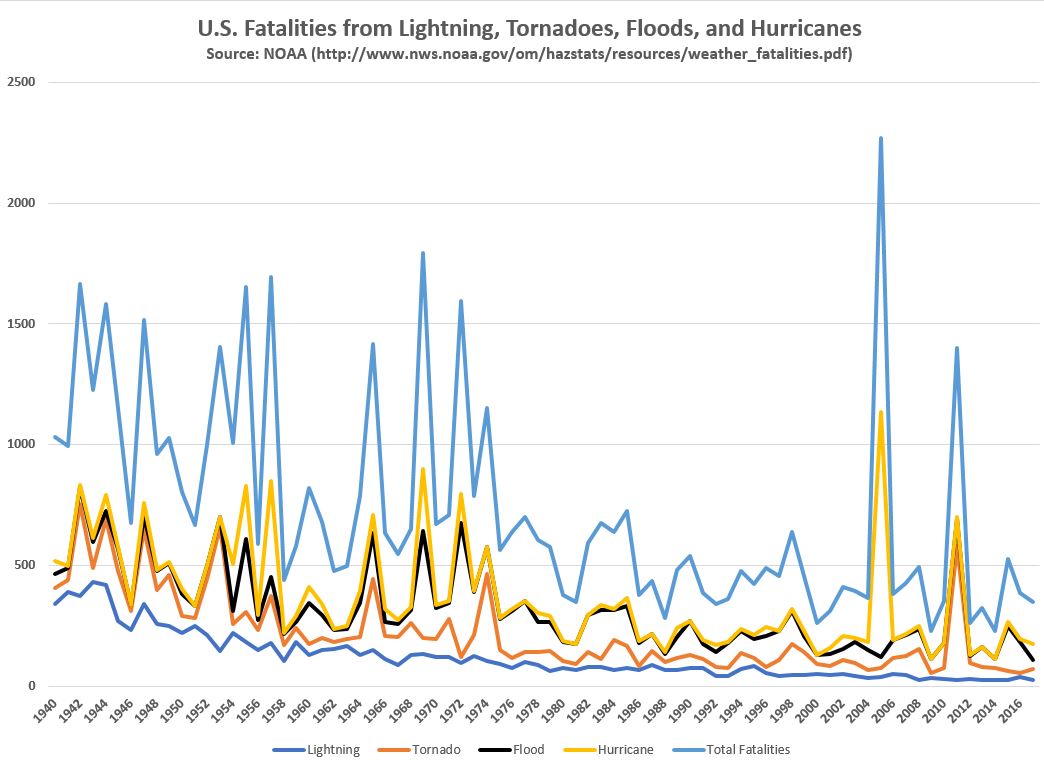

Following Hurricanes Harvey and Irma, I offer this conclusion: We are well down the road in making the necessary adjustments for global warming. Through our forecasting advancements, improved early warning systems, and better coordinated relief efforts, we are seeing a tangible decrease in the human tolls from weather events when compared to the past (see chart below).

Furthermore, the estimated property damage from Harvey and Irma, while historic, was predictable given the economic growth we’ve seen in the past 30 years along our hurricane-vulnerable coastlines.

This does not mean we can ignore climate change as many (but not all) Republicans want to do. More property and people are exposed to the threat of hurricanes and coastal flooding than at any time in our history, according to AIR Worldwide, an insurance analytics firm. The number of Americans living in coastal counties grew by 84% between 1960 and 2008, compared to 64% in non-coastal counties, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Sadly, as evidenced in the tragic death of eight nursing home residents in Hollywood, Florida, our most vulnerable populations — the elderly and the poor — bear a disproportionate share of the risks associated with severe weather events.

Much more needs to be done to secure our coastlines: updating zoning laws, improving building codes, disaster management training, protecting our power grids, insurance reform (including improved fraud detection), and population relocation subsidies.

“The rising level of the oceans, the growing coastal population, the additional development associated with it, and the possible increasing severity of storms mean that people and property are increasingly at risk,” says Dr Tim Doggett, an environmental economist for AIR Worldwide. “Coastal communities have three options when it comes to dealing with this enhanced risk of flooding. Defend the shoreline with man-made or natural barriers, adapt by raising structures and infrastructure above projected flood levels, (or) retreat.”

But, if Texas’ and Florida’s preparations and responses to Hurricanes Harvey and Irma are any indication, the U.S. is starting to meet the challenges of climate change and, particularly with respect to protecting human life, appears capable of withstanding its future challenges.

How do we know this? Lets go to the data.

When looking at the number of fatalities across a wide variety of weather-related events (lightning, tornadoes, floods, and hurricanes), the trend has been downward since the 1970s. The years 2005 and 2012 (Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy) are the obvious deviations from this trend. By comparison, if we annualize the weather-related deaths so far in 2017, even with the fatalities related to Hurricanes Harvey and Irma, the estimated number of weather-related deaths are consistent with the long-term downward trend.

Americans are better able to withstand the impacts of extreme weather events today than at anytime since 1940. That finding should be no surprise to anyone working at the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), NOAA or any other weather and public safety organization in the U.S. We have the tools and technology to predict and prepare for almost any major weather event.

Yet, fatalities are just one simple measure of our ability to confront unpredictable weather events. Weather’s economic costs are also important and, in that regard, the story is more complicated.

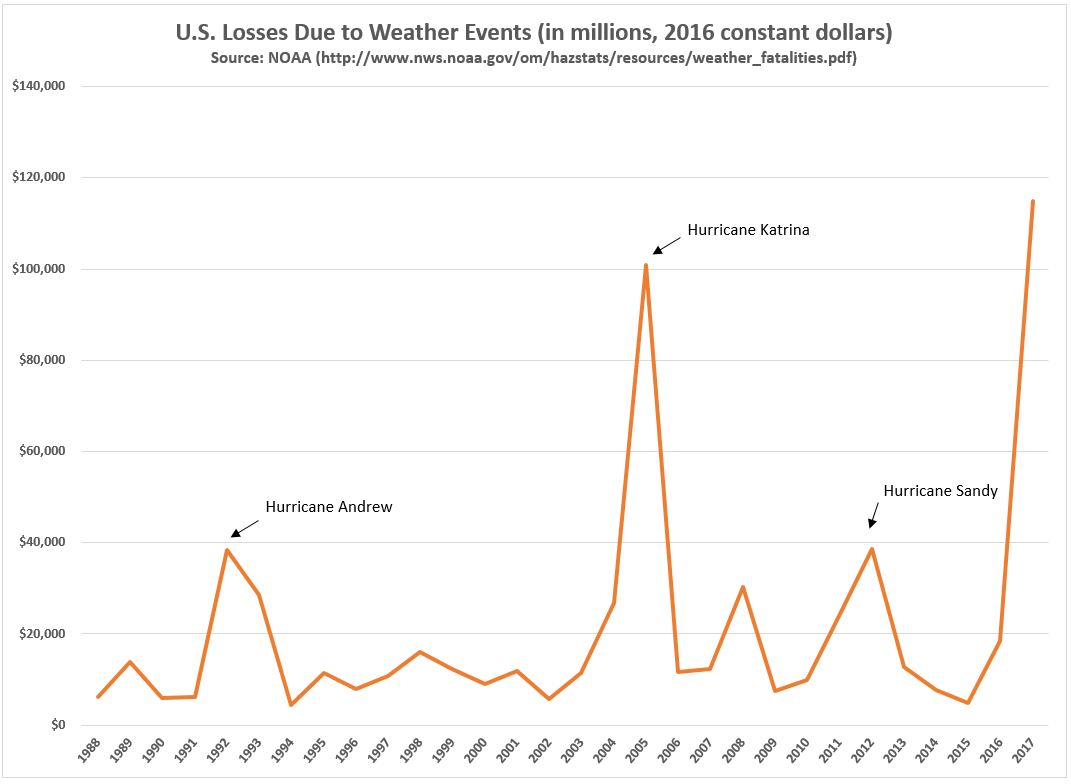

NOAA data on weather-related economic costs shows a relatively predictable year-to-year financial impact in the U.S. Since the late 1980s, the U.S. has not seen any substantive increase in damages due to weather events…….until this year (see graph below):

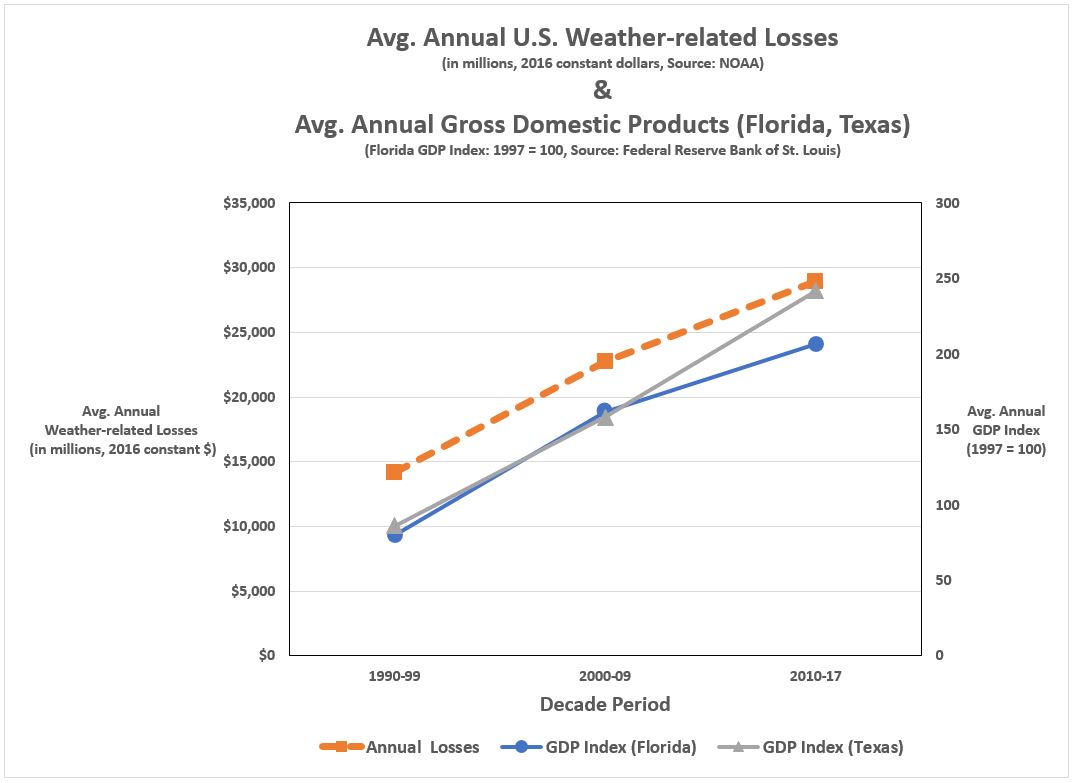

Two Category 4 hurricanes hitting our shores will do that. Damages from Hurricanes Irma and Harvey combined are expected to exceed $115 billion, according to Goldman Sachs. Even controlling for monetary inflation, the economic costs of weather events have increased in the U.S. since 1990, from around $15 billion-a-year to around $30 billion-a-year (see chart below).

But why?

With good reason man-made climate change (anthropogenic global warming) is high on that suspect list and the empirical evidence is growing that global warming is causally linked to the increased probabilities of extreme weather events such as heat waves, droughts and flooding.

There will be no effort here to challenge that conclusion as the scientific evidence grows, literally, by the day. However, implicating climate change in the unparalleled economic costs of Hurricanes Harvey and Irma is not necessary.

Indeed, such attribution may distract from this country’s most cost-effective tools for addressing the effects of climate change: improved building standards and materials, strict zoning laws limiting new commercial and residential development in flood prone areas, and subsidies to low-income and elderly Americans to aid in their relocation out of areas prone to extreme weather events.

Our country must also move quickly to balance our national, state and local budgets so that we can start building up “rainy day” funds to address the unpredictable costs of climate change. If Hurricanes Harvey and Irma have a positive side it is for sounding the alarm that climate change could get very expensive very soon. In fact, it already is expensive.

[Side note: Democrats, this might not be the time to push universal health care. I’m just suggesting for consideration: if you are going to continue two military occupations in the Middle East AND fund universal health care AND prepare for climate change, our country may have to start making hard choices…

…Oh, and this administration is considering a military intervention in North Korea. Just one more potential stressor on a national government debt that is already around 88 percent of annual GDP, according to the International Monetary Fund. That level of debt puts us in the company of the UK, France, Ireland, and Italy. While not an unsustainable level of debt for an economy like ours, it still brings major constraints on any new, big budget items.]

Back to the more immediate issue at hand…

Extreme weather, economic growth, and government spending are closely linked.

The yearly weather-related damage totals in the previous graphic reveal significant variation from year-to-year — which is one reason it is useful to combine annual totals into higher-order aggregates.

If we aggregate weather-related economic costs to the decade-level and compare this to economic growth in Texas and Florida (serving here as proxies for the economic growth of hurricane-vulnerable coastal areas in the U.S.), we see a strong relationship:

Over the past three decades, the increase in total damages from weather events tracks closely to economic growth in the coastal states of Texas and Florida, where wealth and property development increasingly pepper the coastlines.

Going forward, the U.S. can expect around $30 billion in weather-related damages from one year to the next. Without a lot more data, however, we must assume for now the weather-related damages from Irma and Harvey are outliers, not the new normal.

Courtesy of Inside Climate News, we get this fantastic graphic showing new building developments in downtown Ft Lauderdale, FL that are likely to face storm-caused flooding problems in the future. Readers should note, however, that near-term global-warming-caused sea level rises aren’t going to be anywhere the +1, +2…, or +6 feet shown in the graphic. However, storm surges from hurricanes are more than capable of reaching +6 feet.

In the presence of rising sea levels, Ft. Lauderdale’s urban planning strategy does beg the question: What the hell are they thinking? Building high-density residential buildings on low-elevation tracts of land is just dumb — dumb even for Florida.

SINCE WE ARE ALREADY DOING A GREAT JOB, CAN WE JUST IGNORE GLOBAL WARMING?

I am not a climate change alarmist (as the title of this essay should make obvious), but we cannot ignore global warming either. It is happening. That is not a fiction created by the mainstream media, Al Gore or the Chinese. The first place we can start preparing is in where we place new building developments.

Unlike Ft. Lauderdale, many forward-leaning coastal cities in the U.S. are preparing for rising sea levels. New York City has invested significantly into its flood prevention plan and a coalition of Miami-Dade County, FL leaders are laying out five-year city plans that account for increasing sea levels. Why only five-year plans?

“Nobody knows what things are going to look like in 50 to 100 years,” Nicole Hefty, the head of Miami-Dade County’s Office of Sustainability, told The Atlantic‘s Amy Lieberman. “We can speak for smaller years and adapt in that way.”

Not a bad strategy. Being too ambitious too soon can do more harm than good given finite local, state and national budgets.

Any decisions looking beyond five years can be “rendered irrelevant by the rising seas,” writes Lieberman.

Furthermore, the economic impact of global warming, as measured by dollar damages and deaths, has so far been manageable. Even with the historic nature of Irma and Harvey , the U.S. economy will likely lose only about 0.8 percentage points in 2017 third quarter growth, according to Goldman Sachs. That still leaves the American economy chugging along at a 2-percent growth rate. Not exactly booming, but not recessionary either.

What climate change scientists and media forget to tell us is that global warming is not a planet killer or a human-level extinction event (though New Zealand’s tuatara, a lizard-like reptile whose eggs produce females only when nests are cool, are not so lucky).

Nonetheless, we face an uncertain future as we continue to put more development and economic wealth in the path of future weather events.

AIR Worldwide estimates that the total value of insurable property in ZIP Codes potentially impacted by storm surge is $17 trillion (USD). If, as a society, we spend the majority of our time and money trying to phase out the oil and automobile industries, we will fail to directly address the real challenges posed by climate change.

Our coastlines will always be a point of destination for Americans for settlement and entertainment, so we need to better control coastal property development. Trying to slow or even reverse global warming may be too expensive or ineffective, and diverts resources away from more effective climate change mitigation tools over which we have more predictable control.

The planet will continue to get warmer — nobody should doubt that. How warm will depend on the extent and quickness with which we convert to renewable energy sources. But politicians and activists need to keep their expectations realistic on that front.

Forecasts on the U.S.’s conversion to renewable energy sources offer little optimism for those expecting all of our country’s energy needs will in their lifetime come from renewables. That is not likely to happen.

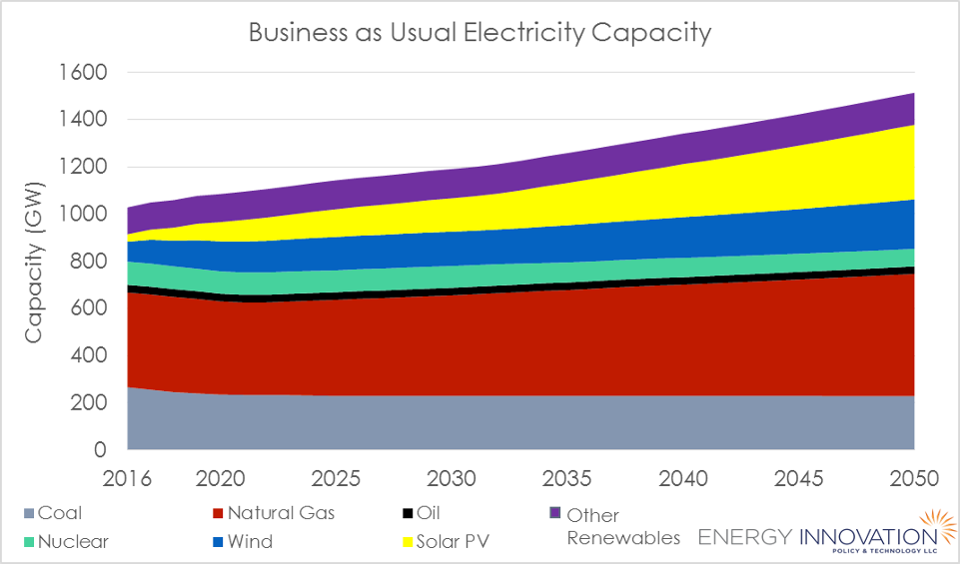

By 2050, Energy Innovation, an energy and environmental industry consulting firm, estimates 35 percent of U.S. electricity capacity will come from the combination of solar and wind power, up from about 15 percent today.

While some optimistic forecasts see much more than 50 percent coming from solar and wind power by 2050, they assume capacity growth for solar photovoltaic (PV) and wind will continue at current high rates. Unfortunately, solar and wind’s high growth rates are due in part to the small percentage from which they start (see the yellow and blue shaded areas in the chart below).

U.S. cannot afford building castles in the sky with respect to renewable energy when it has more immediate policy tools at its disposal to combat the effects of climate change.

As the planet warms, and it will, Americans need to make better decisions about where they live and play and how they prepare for future extreme weather events. Though generally ridiculed in the media as just another form of climate denialism, climate realism strikes a balance between the realities of global warming and our economic and social capacities to address it in a substantive way.

Climate realists don’t see the term ‘adaptation’ as a dirty word as does the climate change lobby. Whether we use public policy to adapt to climate change is a political question. If our political leaders don’t see the necessity of adapting that job will be left to us as individuals.

Despite little attention from the media, our cities and states are making significant adaptations along their shorelines and internal waterways necessary to weather climate change (pardon the pun). This will continue with or without our national politicians, who seem incapable of doing anything these days.

Local economics are dictating these adaptations — any maybe that is the best way to do it anyway. Our national politicians are too busy failing us in other areas.

About the author: Kent Kroeger is a writer and statistical consultant with over 30 -years experience measuring and analyzing public opinion for public and private sector clients. He also spent ten years working for the U.S. Department of Defense’s Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness and the Defense Intelligence Agency. He holds a B.S. degree in Journalism/Political Science from The University of Iowa, and an M.A. in Quantitative Methods from Columbia University (New York, NY). He lives in Ewing, New Jersey with his wife and son.