By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; November 9, 2018)

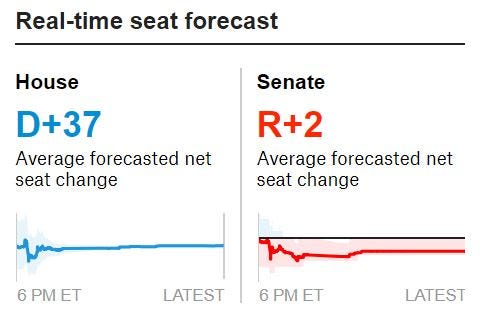

The NuQum.com statistical model, which employed variables measured six-months prior to the actual 2018 midterm election, predicted the Democrats would gain 39 seats in the U.S. House. As of mid-morning on November 8th, the Democrats are most likely to have gained 37 seats according to Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight.com.

I normally don’t toot my own horn, but ‘toot toot.’

In truth, forecasting the number of U.S. House seats gained or lost by a particular party during a midterm election is relatively easy, at least compared to other more difficult political forecasts such as ‘Who will be the Democratic presidential nominee in 2020?’ (Kamala Harris) or ‘Will Donald Trump run for re-election in 2020?’ (No) or ‘Will Nikki Haley run for president in 2020?’ (Yes).

One of the basic issues in judging statistical forecasts is how to weight the time in which the forecast is made. Which is more valuable to an organization? A precise prediction made within days of the outcome? Or a less precise but directionally accurate prediction made months prior to the outcome?

By training and temperament, I prefer the latter. My experience has also been that most organizations prefer the latter as well…with the exception of the American news media. The news media’s business model is built on the day-to-day drama of modern American electioneering. After all, the cable news channels have 24-hours of inventory to fill every day.

But the question should nonetheless be asked, ‘Are the millions of dollars spent by news organizations leading up to a midterm election on polling and data analysis worth the effort?’ ‘What did the time, effort and expenditure of resources gain them?’

In terms of understanding the factors influencing the 2018 midterm outcome, the news media’s effort in the past three months has been worth almost nothing. Yes, news and political junkies were entertained by the daily horse race statistics; but for the average American, there was very little substance to be found within the last three months of election news coverage.

We knew six months ago the Republicans would not only lose control of the U.S. House, but would lose somewhere in the neighborhood of 40 seats.

That is what happened, minus two or three seats. This election was set in stone months ago and there was little, short of an unpredictable shock to the political ecosystem like a stock market collapse or a surprise military attack against us, that was going to change the final result.

This past midterm election was one of the ugliest and most unenlightening in my lifetime. Unlike the 1994 and 2010 midterm elections, which were genuine wave elections that went beyond merely a referendum on the incumbent president and revealed a genuine political shift within the country, the 2018 election was largely unspectacular and offered few insights on the where this country is politically or ideologically headed.

The 2018 midterm election was, first and foremost, the American people’s judgment on the first two years of Donald Trump’s time in office; and for some, no doubt, it was their judgement on how Donald Trump rose to the presidency. His presidency will never be legitimate in their eyes.

For the most part, this was not an ‘issue-based’ election, with two possible exceptions: health care (Obamacare) and immigration. While it is inaccurate to suggest the 2018 midterms “cemented Obamacare’s legacy,” as some pundits have suggested, the election did show there is still life in the Obamacare and the Democrats have the better argument on health care.

Health Care

Health care was the top issue among 2018 voters and, today, the Democrats are best aligned with public sentiment on the issue.

“Voters in Idaho, Nebraska and Utah approved ballot initiatives to include in their Medicaid programs adults with incomes of up to 138 percent of the federal poverty line,” notes Washington Post political reporter Amy Goldstein. “The results accomplish a broadening of the safety-net insurance that the states’ legislatures had balked at for years.”

In addition, she points out, “Maine voters elected Democrat Janet Mills as governor, clearing the path for a Medicaid expansion that voters approved by referendum a year ago.”

The health care issue helped Tony Evers beat incumbent Republican Scott Walker in Wisconsin and was the top issue among Kansas voters who led Laura Kelly to victory against Republican Kris Kobach. Both Evers and Kelly support Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion in their respective states.

We are talking Kansas here. Kansas voted to expand Medicaid! That is a big deal. Kansas, like many other parts of the country, found health care and immigration to be top two issues among voters. Clearly, health care was a winner for Democrats in the midterms.

It may be time for Republicans like New York Representative Peter King to stop blindly saying ‘the American health care system is the best in the world’ when clearly it is not. In the aggregate, when compared to other advanced economies, we eat up twice as much of our national economy on health care and still end up with inferior health outcomes.

If the worst criticism Rep. King (New York) can come up with against the Canadian single-payer system is that they have to wait eight weeks for an MRI (I had to wait six weeks for mine), I’m willing to take may chances with government-run health care. And, increasingly, so are most Americans.

Health care is one issue where the general population often knows more about the complexities of the system than the politicians. Many people interact with the health care system on a weekly or even daily basis. They know the problems with our health care system on a personal level: health insurance premiums taking more and more out of paychecks, drugs that are too expensive, and household budget-busting out-of-pocket costs are among the many issues Americans face every day.

Immigration

Immigration, on the other hand, is more complicated and neither the Democrats or Republicans seem to fully appreciate the ambivalence many Americans feel about the issue.

In terms of overall public opinion, Americans understand the value of immigration, but prefer legal immigration and do not support increasing current immigration levels, according to recent Gallup Poll data. The Democratic Party emphasizes the ‘social value of immigration’ while the Republican Party understands the ‘legal immigration’ part. Neither party, however, seems prepared to put these complimentary attitudes together into a coherent policy platform.

Trump’s stoking fears about the ‘caravan’ and illegal immigration in general may have saved some Republican politicians in Florida, Texas and Arizona who seemed destined to lose in 2018, but will that strategy work across a larger swath of the country in 2020?

Voters care about their reality, not ideology

One of the biggest mistakes politicians and political consultants make is the assumption that Americans have an ideological preference (even if their own opinions do not hold together in any coherent ideological pattern).

At every opportunity, filmmaker Michael Moore loves to say ‘America is a liberal country.’ He is among many liberals and Democrats that insist this is true.

They couldn’t be more wrong.

Analysts should never take the results from a national opinion survey, add up those issues where Americans take the ‘liberal’ position versus where they take the ‘conservative’ position, and then declare: ‘The American people are left-of-center.’ Or whatever the conclusion might be in the context of that survey.

That is not how the human mind works.

Opinion surveys are mirrors on the most recent political campaign (which are usually fought along partisan and ideological lines, though not always). Surveys reflect the ideological nature of the political system (elections, politicians, political institutions, policy debates etc.), not necessarily the ideological nature of the American people.

On a political spectrum, Americans are largely non-ideological — as opposed to a country like France where political ideology has a more palpable meaning and manifests more noticeably within their political ecosystem. Americans, in contrast, have a founding culture of muscular individualism that reflexively rejects collective or group-based ideologies, to the point where anytime one ideology appears too powerful within the political structure, Americans instinctively knock it down. It is in our political DNA to do so.

That is what Americans do best and will do again against the Democrats in 2020 if they over-reach given their regained power. The same, of course, is true when the Republicans over-reach.

Americans do not generally seek politicians that agree with their left- or right-leaning ideology, they seek politicians that align with their personal perception of reality. ‘Does a political party or candidate speak to my reality?’ is the question on voters’ minds. It is the politicians and intellectual class that map voters’ reality-based way to thinking to the ideological spectrum. But they do so at the risk of misinterpreting the public mind — which politicians and the news media are already doing with respect to the 2018 midterms.

- K.R.K.