By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, October 5, 2017)

{Feel free to send any comments about this essay to: kkroeger@nuqum.com or kentkroeger3@gmail.com}

The alarmists and deniers dominate the climate change debate on the cable news networks, but neither dominate U.S. energy policy.

Climate realists are driving American energy policy and there is little reason to think the Trump administration can reverse the climate change initiatives already in place.

Today’s federal court ruling upholding the Obama-era EPA methane rules punctuates this fact.

Who are the climate realists? They are the forces driving the rise of natural gas for electricity generation concurrently with the development of renewable sources such as wind and solar. They include industry executives in the oil and gas sector, Wall Street investors, environmentalists, government bureaucrats, the courts and the major congressional committees overseeing our nation’s energy policies.

Are the climate realists just another arm of the Deep State? Perhaps. Whoever they are, they are not hindered by our nation’s hyper-partisanship. Instead, a massive realignment of our nation’s energy production and consumption mix is well underway and not even President Trump and EPA Chief Scott Pruitt can stop it.

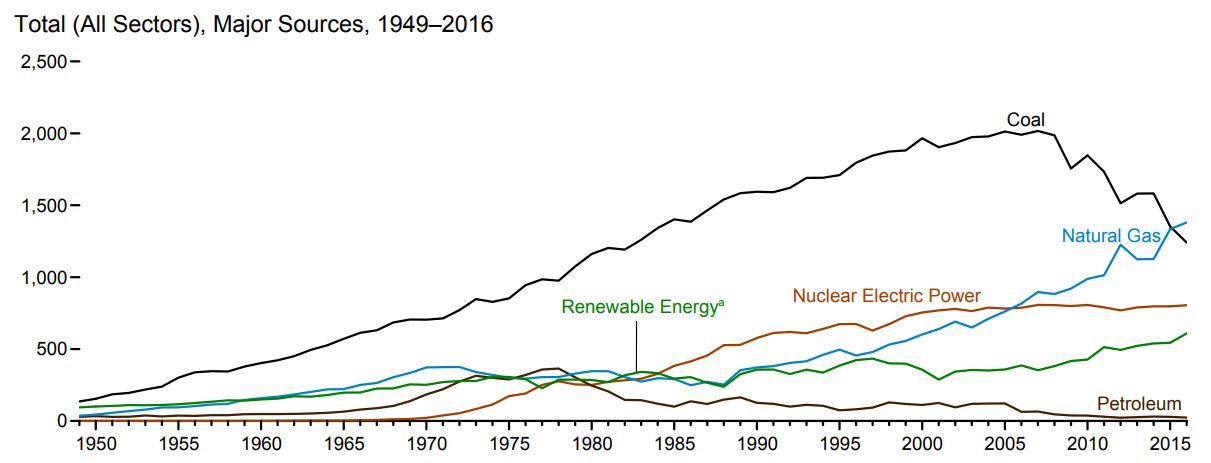

Since 2000, the U.S. has restructured the nation’s electricity generation mix away from coal and towards cleaner energy sources, such as natural gas and renewables.

Primary Electricity Net Generation in U.S. from 1949 to 2016 (Billion kilowatt hours)

Coal peaked at 2 trillion kilowatt hours in 2008 and has been in decline ever since; whereas, natural gas has been rising as a source of electricity generation since the late 1980s. Today, coal and natural gas each account for 33 percent of total U.S. electricity generation.

As for renewable energy sources, no politician receives less credit than George W. Bush for pushing the advance of green energy. As the governor of Texas, Bush signed legislation that created a renewable electricity mandate so that today Texas leads the nation in wind generating capacity.

President George W. Bush more than once pushed Congress to extend the production tax credits for renewable energy sources, particularly wind power. Bush’s policies had the tangible result of increasing renewable energy’s share in U.S. electricity generation from 10 percent in the early 2000s to about 15 percent in 2016.

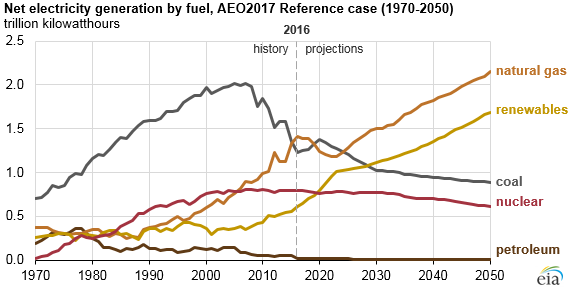

According to U.S. Energy Information Agency (EIA) forecasts, by 2050, renewable energy sources will account for about 30 percent of U.S. electricity generation, putting it behind only natural gas (40%) as the largest contributor. Coal will account for around 17 percent.

A number of assumptions underlie the EIA U.S. energy forecasts, one of them being the continued implementation of the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan (CPP), which is already under threat from the Trump Administration’s executive order in March telling the EPA to kill it.

Easier said than done. Since the CPP has already gone through the full federal rulemaking process, ending it will require a similarly laborious process. As of today, the CPP still stands, if only barely, and the federal judge hearing the opposition to the CPP by 27 states — including EPA Chief Scott Pruitt’s home state of Oklahoma — has ruled that the Trump administration must offer its new course of action in lieu of the CPP by October 6th.

To CPP advocates, the endless mélange of arcane legal procedures and bureaucratic stodginess may appear impenetrable, but this is what happens when the federal executive and legislative branches stop working together and economic policy is implemented through executive fiat. Throw into this political mosh pit over half of the state attorney generals trying to kill the CPP and it is fair to ask, what chance does the country have at changing its national energy policies on a scale that can possibly address climate change?

It turns out, the chances are looking pretty good — though three more years (at least) of the Trump administration is likely to sap some of that optimism.

THE U.S. IS RAPIDLY CONVERTING TO A CLEAN(ER) ENERGY ECONOMY

The major trends are undeniable. Coal is rapidly being replaced by natural gas and renewable energy (wind, solar, geothermal, hydroelectric) as the primary sources of U.S. electricity production. Recent increases in coal electricity production in 2017 are not likely to change these trends as many coal energy plants are scheduled to be shutdown over the next decade.

Along with the decline of coal, there are four other macro trends that will drive U.S. energy production and consumption over the next 30 years:

- Natural gas will continue as a stop gap energy source until renewables become more cost effective and reliable.

- Cost decreases in renewable energy generation will continue and spur its future growth

- While renewable energy will continue to grow, it will not be fast enough to see the effective end of fossil fuels by 2050 (as required by the Paris Accords) unless major efficiency improvements occur in energy production and use.

- The U.S. will not see nuclear power playing a significant role in replacing fossil fuels (but that will not the case in China and India).

How did this all happen? Our elected leaders notwithstanding, the other players in the making U.S. energy policy (Big Oil and Gas companies, federal bureaucrats, regulators, the environmental lobby, and public opinion) have opted for a realist view of global warming.

When the Trump administration decided unilaterally to relax the regulatory requirements for limiting the escape of methane gas during the natural gas extraction process, the environmental lobby weighed in, but did so without undercutting the importance of natural gas in addressing climate change.

“(The Trump administration) listened to a few industry players eager to cut costs and to maximize profits in the short-term, while shirking their responsibility to help America’s booming natural gas industry stay competitive for decades to come,” said Ben Ratner, Director of the Environmental Defense Fund’s (EDF) Corporate Partnership’s Program.”States such as Colorado show that methane leaks, can, in fact, be managed cost-effectively and without harming production.’

So who are the Big Oil and Gas industry players like Exxon-Mobil siding with on this issue? The EDF and the climate change lobby, of course.

What?

“The major multinational oil and gas producers like ExxonMobil and Shell have said they are already following methane pollution rules finalized by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency last year (2016),” says Jon Goldstein, Director for Regulatory and Legislative Affairs at EDF. ‘Better to anticipate future compliance issues today and bake them into your forward planning, than to be caught flatfooted tomorrow.”

That is climate realism as practiced by Big Oil and Gas.

Popular culture views oil executives as derivative forms of Dallas‘ J.R. Ewing. In reality, they are often Ivy League educated business managers with the education and experience to know that risk must always be managed, not ignored. The geologic and political realities underlying fossil fuels leave just one outcome. Fossil fuels will not be the dominant energy source by the end of this century.

As regressive as the Trump administration has been on climate change policy, there is little they can do to change the global trends. Recent increases in coal electricity generation is illusory. Coal is dead. Instead, the central question facing U.S. policymakers is the extent to which natural gas extraction — including the use of fracking — is going to continue. When does natural gas stop being a stop-gap measure?

Even the most alarmist environmental lobby groups recognize that natural gas has driven the recent reductions in U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. But what divides them from climate realists is their long-term view of natural gas. The alarmists will not accept an energy source (natural gas) that is only 50 percent cleaner in its greenhouse gas emissions than coal.

Climate realists, in contrast, consider the economic risks and disruption associated with a crash program to replace fossil fuels with renewable energy sources. And economists are quick to point out that recent public and private investments in clean energy have been full of fits and starts. Forbes reported in June that “new investment in clean energy fell to $287.5 billion in 2016, 18 percent lower than the record investment of $348.5 billion in 2015 and 9 percent lower than the $315 billion invested in 2014.”

Climate realists want the trends to be in the right direction, while the alarmists want a worldwide “Man on the Moon”-like resolve to see the practical elimination of fossil fuels by 2050.

This is what divides climate alarmists from realists and it represents a mighty big chasm. The good news is that both groups agree (for the most part) on the basic science behind global warming.

ALARMISTS AND REALISTS AGREE: THE EARTH IS WARMING AND HUMANS ARE TO BLAME

Let’s immediately dispense with the scientific nonsense promulgated by those who claim the science is still unsettled. Yes, of course, some aspects of the science is unsettled. But here is what the climatologists are telling us:

The planet’s recent warming is due largely to human activities. This additional warming is not due to natural variation. It is due to the accumulation of greenhouse gases (particularly CO2) in the atmosphere.

Here is a fun little graphic from SkepticalScience.com contrasting the two contradictory views on global warming:

Even many hardcore climate change skeptics (like myself) are moved by the growing empirical evidence.

Climate skeptics are not swayed by peer pressure, which invites bias and herd mentalities. And don’t bother them with the ’97 percent of climatologists’ agree argument. That figure was basically pulled out of Harvard researcher Naomi Oreskes’ ass 17 years ago. Only recently has a meta-analysis of published research found some credence in that ’97 percent’ figure — but only after researchers ignored the majority of climate change research papers that did not take any stand regarding global warming.

Science isn’t a democracy and facts are determined by vote counts. I’m sure at some point 97 percent of physicists ascribed to the Steady State Theory of the Universe. Scientists can get things really wrong sometimes.

Instead, only evidence matters and it has been unequivocal on global warming.

Even under the new administration, NASA’s offers a convincing summary of the data evidence behind the conclusion that recent global warming is anthropogenic (human-caused):

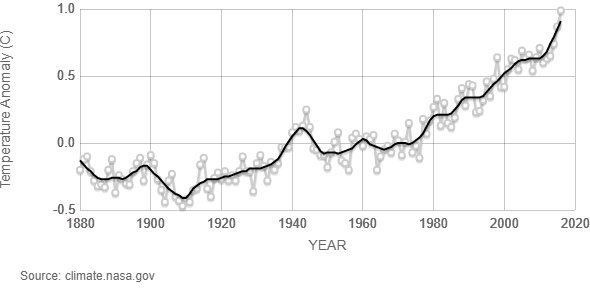

Figure 1: GLOBAL LAND-OCEAN TEMPERATURE INDEX

However, the most compelling evidence was offered in 1990, when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published its first forecast for global temperatures. It was impossible to know at the time, but the report’s forecast for global temperatures was relatively accurate, despite being based on a simple statistical model driven primarily by the increased concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

The 1990 IPCC report forecast an increase global temperatures between 0.10 to 0.35°C per decade. In actuality, global temperatures have risen 0.15°C per decade since the 1st IPCC forecast.

“The IPCC models do an impressive job accurately representing and projecting changes in the global climate, contrary to contrarian claims,” says science writer Dana Nuccitelli. “In fact, the IPCC global surface warming projections have performed much better than predictions made by climate contrarians.”

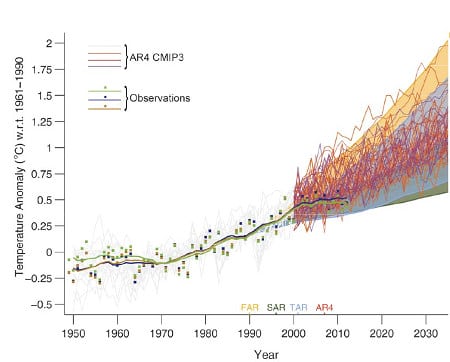

Figure 2: SUMMARY OF IPCC REPORT FORECASTS

‘Impressive’ may be an over-statement as the 1st IPCC Assessment Report (yellow shaded region in the above graph) over-estimated global warming; however, the 3rd and 4th IPCC projections were better. That is to be expected. Over time, the models should be better.

Global temperatures are rising. And by using ice core data to model climate dynamics over long periods of geologic time, the evidence also supports the connection between rising global temperatures and the increased concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

What is the exact sensitivity of global temperatures to greenhouse gas concentrations?That’s a complicated question well beyond my background, so I will let the climate scientists debate over the answer. For the hopelessly curious, the Skeptical Scientist website offers a layman-friendly discussion of this complex issue: HERE. [My personal fear is that climate scientists exaggerate humankind’s ability to modulate global temperatures through the manipulation of greenhouse gas emissions alone.]

HOW CAN WE MAKE PUBLIC POLICY AROUND GLOBAL WARMING WHEN THERE IS SO MUCH SCIENTIFIC UNCERTAINTY?

One reason we see variations in the global temperature forecast models is that the scientific groups making the forecasts use different specifications and parameterizations of this temperature/greenhouse gases relationship.

Here is the good news: Eventually, climate scientists will determine which models best predict global temperatures…but it will take time…measured in years. But the best models will reveal themselves, that is certain.

In the meantime, does the world have the luxury to wait for the perfect answer. Sometimes (maybe always?) policymakers are forced to work with the 80 percent solution.

We all know the phrase — ‘better being the enemy of the good’ — popularized by Voltaire. But I like John Lennon’s version. When asked by a journalist when he knew if a song he was writing was finished, Lennon replied, “I stop writing when the song is good enough.”

The climate models are far from perfect, but they are good enough to make substantive policy decisions. The problem for climate alarmists however is that those policy decisions may not go far enough for them.

Policy making in a pluralist democracy like ours is driven by a multiplicity of relatively small and autonomous groups. Despite what Bernie Sanders says, no single group of elites dominate our policy process.

Thus, scientists are not empowered to dictate public policy on climate change but must instead fight it out with other political factions and organized interests. Madison, Jay and Hamilton envisioned our system to work that way for good reason.

The structure of our political system has profound implications on policy making. It encourages small changes over large, dramatic changes in policy.

Political scientist Charles Lindblom described the incrementalist predisposition of American policy making in his famous 1959 essay, “The Science of Muddling Through.” Since incrementalism failed to explain large policy shifts, however, Lindblom’s original model was supplanted by the punctuated equilibrium model of policy making which says major policy changes will occur over brief periods of time, followed by longer periods of incremental policy changes.

How the world addresses climate change is the ultimate policy model case study.

THE CHOICE: INCREMENTALIST ACTION VERSUS DRAMATIC POLICY SHIFTS

Collectively, the world has three possible policy approaches to climate change. They are: (1) Do nothing or the ‘wait and see’ approach (Deniers), (2) Incremental decisions as events demand (Realists), or (3) Dramatic policy shifts now in anticipation of the future (Alarmists).

All three approaches have strengths and weaknesses:

| Policy Model | Strengths | Weaknesses |

| Wait and See | Short-term costs are minimal; policy flexibility (in the short-term, at least) | If worst-case scenarios occur, policy flexibility reduced; overall costs extremely high |

| Incrementalism | Modest costs in short-term; hedges fiscal bets in case worst-case scenarios don't materialize; maximum policy flexibility | Inadequate policy responses in short-term may exacerbate problems in the long-term; high long-term costs under worst-case scenarios |

| Dramatic Policy Shifts | Lower overall costs if worst-case scenarios prove correct | High costs in short-term; if initial policies inappropriate to the problem, long-term costs at fiscal bankruptcy levels. |

As to which policy is adopted will be partially driven by political leaders’ level of confidence in the empirical data. Alarmists accept the scientific evidence as irrefutable and deterministic. There is no need for political debate. Deniers reject the evidence as flawed and driven more by partisan agendas. And realists see the empirical data as credible but probabilistic.

Scientists do not make the policy decisions. That is not their domain of expertise. Policy making is the domain of the political class.

Unfortunately, that’s where the climate change debate becomes contentious. Throw in a healthy serving of Donald Trump and Scott Pruitt (with a dash of Rick Perry), and the debate is dysfunctional.

We can ignore the deniers as their policy goal is the simplest of all — do nothing. However, as already shown, the world’s energy production and consumption has already changed in significant ways and the deniers long ago lost control of policy making process. They are nearly irrelevant (even though control the U.S. executive branch right now).

The other two climate groups are relevant.

Climate alarmists see climate change in binary terms — it is “zero net emissions” soon after 2050 or global calamity. There is no middle solution or outcome. This deterministic view of the world — as in, “I know for fact this is going to happen” — places little value on negotiation and compromise. Climate realists, in contrast, are all about negotiation and compromise.

CLIMATE REALISTS ARE RISK AVERSE BY TRAINING AND EXPERIENCE

Climate realists are creatures of the existing policy making system. They see the world through a lens of probabilistic events where there is always a chance that even the most likely events fail to materialize. Furthermore, in the context of large structural budget deficits within the public sector, climate realists incorporate risk assessments into the policy mix which further discourages dramatic policy shifts.

Climate realists bring a healthy skepticism of the science yet are sensitive to its implications. This more sophisticated understanding of the intersection of science and policy place the realists in a better position to dominate U.S. energy and environmental policy.

CLIMATE ALARMISTS WANT TO IMPLEMENT AN ECONOMIC SHIFT AT A SPEED UNPARALLELED IN HUMAN HISTORY

Climate alarmists desire to end the fossil fuel industry within the next 30 years. In other words, divert $33 trillion of capital and assets from one industry to another.

Good luck.

This plan typically includes a carbon tax system (or some equivalent) that would divert around $3 trillion annually from the fossil fuel economy to government entities. These revenues would be diverted into investments in materials and energy efficiency, renewable energy capacity, and the infrastructure necessary to accommodate a 100 percent renewable energy economy.

Alarmists will quickly note that the $3 trillion annual tax levy would ultimately save more money than it raises. Ecofys estimated the savings around $6 trillion per year by 2050.

It’s a big bet. Nothing like it has ever been attempted in human history.

What if global warming comes in at the low-end of the forecasts? The models by design suggest the real possibility.

What if the higher order effects — such as tropical storm intensities, coastal and river flooding, drought frequency, etc. — do not reach levels predicted by the climate models?

What if relatively small investments in improved building materials, better building codes, and smarter zoning and development laws are fiscally more effective than a $3 trillion annual transfer of wealth to the public sector and the nascent clean energy industry.

For the alarmists to achieve a 100 percent renewable energy economy around 2050, a punctuated equilibrium policy change may not be enough. It may require something more revolutionary and disruptive.

Luckily, the climate realists will be pumping brakes on any attempt by the alarmists to change public policy on such a scale.

CLIMATE ALARMISTS GAVE US THE PARIS ACCORDS, BUT THE REALISTS WILL IMPLEMENT IT

The Paris Accords set an aggressive global goal to have net zero carbon emissions early in the second half of this century. The difference in global temperatures between ‘low carbon emissions’ (blue shaded region) and the status quo (red shaded region) is significant:

If the world keeps energy policies at the status quo, by 2100, global temperatures will rise by 4 °C over 2005 temperatures. If we reach near zero net carbon emissions by 2050 (or soon after), global temperatures will rise only 1 °C over 2005 temperatures.

Of course, these predictions assume the global warming models are accurate. Alarmists assume humans can turn down the global thermostat and the globe will dutifully respond. The comedian George Carlin has a nice bit about this noxious type of hubris: It is just another arrogant attempt by humans to control mother nature.

But let’s play along with the idea that we can control global temperatures like the thermostats we use to control our homes’ temperatures. The only chance it happens is if we can reduce greenhouse gas emissions to zero in a relatively short period of time. [Some scientists fear it may already be too late to prevent the globe’s temperatures from exceeding 2 °C over pre-industrial temperatures.]

From a policy perspective, getting to Paris Accords’ zero net carbon emissions target is problematic given current global reliance on coal and natural gas energy production and existing plans to build new coal and natural power plant.

Forecasts on the mix of energy sources in 2050, not surprisingly, vary significantly depending on what group is making the forecasts.

The following forecasts illustrate this variance.

A PLAN TO GET TO ZERO EMISSIONS BY 2050 (or soon after)

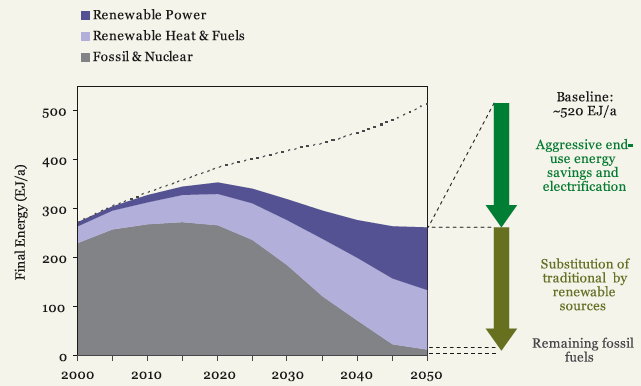

Energy consulting firm Ecofys produced a report in 2011 demonstrating the plausibility of ‘net zero emissions’ by 2050. In their forecast model, half of the ‘net zero emissions’ goal is met by reducing energy demand through increased energy efficiency, and the remaining part of the goal is met by the substitution of traditional energy sources with renewable sources (see chart below).

Ecofys’s forecast is aggressive and predicated on a number of strong assumptions and stretch goals, including:

- Global energy demand in 2050 will be 15 percent lower than in 2005, despite a growing population and continued economic development in countries like India and China.

- Create buildings that require almost no conventional energy for heating or cooling and have all new buildings meet this standard by 2030.

- High growth rates in solar energy production will continue or decline only slightly

- Growth rates in wind power will also continue so that it will provide one-quarter of the world’s electricity needs by 2050.

- Scientific and technology breakthroughs will continue to lower the cost and raise the efficiency of renewable energy sources, energy conservation technologies, and energy (battery) storage capabilities.

- And, finally, the world will collectively accept a carbon tax and levy system that will help raise the money necessary to invest in the other energy goals and milestones.

Not one of these assumptions are likely to hold, much less all of them.

Fueled by economic and population growth, total global energy demand will rise about 33 percent between now and 2050, according to the EIA, and most of this increase will come from outside the U.S. and Europe. To predicate a zero emissions plan on the expectation that American and European policy makers are going to influence domestic energy policies in China and India enough to lower their overall energy demand in 2050 from today’s levels (or 2005!) is laughable.

The safest assumption from the Ecofys plan is that renewables will continue to grow rapidly. British Petroluem’s 2017 Statistical Review of World Energy found that renewable power (excluding hydro power) grew by 14.1 percent in 2016 — which is below the 10-year average, but still robust.

The most promising Ecofys assumption is in solar energy, which recently has seen exponential growth rates. In 2016, there was a 50 percent increase in the amount of new solar power worldwide, bringing its contribution to total worldwide electricity generation to around 1.3 percent.

But Bloomberg’s New Energy Finance Outlook for 2017 is predicting this fast growth in solar power will soon slow down. Luckily for the solar energy industry, the pessimistic predictions on solar’s growth by the International Energy Agency (IEA) and business forecasters like Bloomberg have been notoriously wrong in the past. Of all of the Ecofys zero emissions plan assumptions, continued solar energy growth may be the most likely to materialize.

Where some pieces of the Ecofys zero emissions plan have merit, on the whole, it too dependent on optimism and good intentions. Using the Ecofys plan to represent the ‘zero emissions by 2050’ goal may seem like a straw man argument, but to Ecofys’ credit, the core elements of their forecast includes all of the factors that will need to align in order for the zero emissions goal to be met.

In fairness, Ecofys has removed their 2011 plan for zero emissions from their website, but the assumptions and milestones in the plan are still indicative of the massive challenge the world faces in achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions soon after 2050.

THE FUTURE IS 100% RENEWABLE ENERGY, BUT YOU WON’T BE AROUND TO SEE IT (AND MAYBE NOT YOUR KIDS, EITHER).

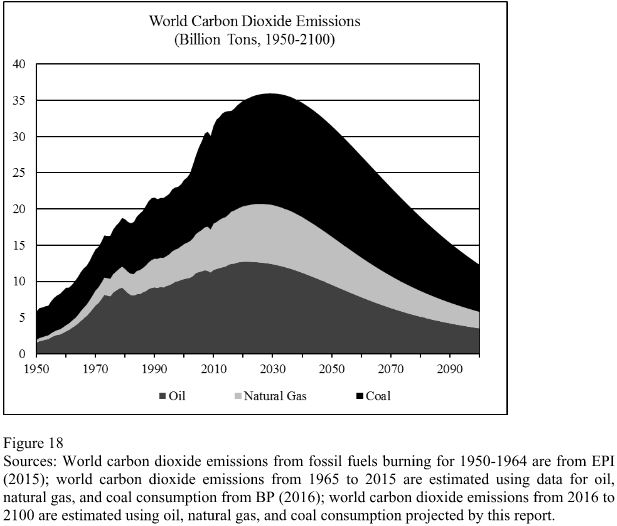

The following global energy forecast was published on the website PeakOil.com and is more indicative of the climate realist perspective and shows us why zero emissions is a challenging goal unlikely to occur anywhere near 2050.

Fossil fuel geeks should be familiar with the Hubbert Linearization method for estimating the level of recoverable natural resources under existing technology, economics, and geopolitical trends. Historically, the Hubbert method has typically underestimated the amount of recoverable oil, gas and coal left in the ground. To mitigate this bias, the PeakOil.com forecast is adjusted using EIA’s official projections on world oil and natural gas production from 2016 to 2040.

Their resulting forecast on world carbon dioxide emissions through 2100 makes the idea of a zero carbon emissions planet seem unattainable, in this century at least.

The good news: these forecasts are products of smart people doing a lot of guesswork. On one level, the idea that carbon emissions will peak around 2030 seems plausible given that we are already deep into 2017 and carbon emissions continue to rise with the growth of the world economy.

Where the PeakOil.com forecast may go wrong is on the downside of the fossil fuel life cycle. If renewables become significantly more cost effective than fossil fuels, the move away from fossil fuels will be much more dramatic than what the above graph shows.

That is the optimist in me speaking.

Significant issues remain ahead for renewables however. The biggest is the cost of solar and wind intermittency.

As University of Houston Lecturer and Energy Fellow Earl J. Ritchie warns, “The continuing decrease in wind and solar costs is a very positive development. However, this trend may reverse as the percentage of variable renewable energy (VRE) – energy that isn’t available on-demand but only at specific times, such as when the wind is blowing – reaches high levels.”

At that point, integration costs become more of a factor in the overall cost of renewable energy.

“When variable sources are a small fraction of electricity supply, the cost of integration is low,” says Ritchie. But when these variable sources become a significant fraction, renewable energy costs can increase. Evidence of this can already be seen in Germany, where wind and solar are heavily integrated into the national power grid.

At what fraction do these costs become significant? It depends.

One study using data from Germany and Indiana found integration costs began to become significant when renewables reached 20 percent of total energy generation. As of 2015, only four countries had variable renewable energy over 20 percent. But that number will rise rapidly in the next 10 years.

THE ABSENCE OF NUCLEAR POWER IN THEIR FUTURE ENERGY MIX SUGGESTS ENVIRONMENTALISTS ARE NOT AS SERIOUS ABOUT CLIMATE CHANGE AS THEY PRETEND

There is one more aspect of the climate change movement that is puzzling. Where is nuclear energy in all of the scenarios where the planet reaches zero carbon emissions?

The task is daunting enough, why make it harder?

Ideological environmentalists need to take off their ideological blinders and accept that the quickest, most direct path to zero carbon emissions is with significant growth in nuclear energy. If safety or nuclear proliferation concerns keep them from signing on to new nuclear power plants, they need to update their information because molten salt (thorium) nuclear reactors may address both of those concerns while maintaining the low carbon emissions aspect of nuclear energy.

Why weren’t molten salt reactors developed sooner? Because countries with the resources to develop peaceful nuclear power also wanted the ability to retool quickly and develop a nuclear weapons program, which the uranium reactors made easier.

Nuclear power is not intermittent like solar and wind. That is a significant advantage. Furthermore, China, India, Brazil, Argentina, and many other large, growing countries are embracing nuclear power on a level to match what the French have already achieved.

Nuclear power plants generate 75 percent of France’s electricity, though that level may fall to 50 percent by 2025 as other renewable energy sources come online. As of today, France is the world’s largest net exporter of electricity due to the very low cost of nuclear power.

Without nuclear power out of the mix, the ideological environmental lobby is making the goal of zero carbon emissions even more unreachable.

NOW WHAT? ADAPT OR DIE.

The major energy sources that work 24 hours-a-day, 365 days-a-year are coal, natural gas, geothermal, hydroelectric (droughts not withstanding), and nuclear.

Renewable energy is still a supplemental source of power. Without fundamental advancements in energy storage technologies, countries will still need continuous power sources on cloudy and windless days.

And this essay hasn’t even touched transportation.

Throw in combustion engine automobiles likely to be in use in 2050 and the belief that this world can be anywhere close to ‘zero net carbon emissions’ anywhere near 2050 is fantasy.

This means global temperatures are going to come in somewhere in between the ‘status quo’ and ‘zero net emissions’ scenarios. In other words, by 2100, global temperatures may be close to 3 °C above pre-industrial temperature levels. At that level of global warming arrives increases in ice sheet melting and the impact of the slow climate feedback mechanisms which may push the warming to 6 °C above pre-industrial levels, regardless of any carbon emissions reductions that occur after we hit the 3 °C milestone.

At 6 °C above pre-industrial levels, our descendants will be seriously pissed at us for failing to do more to slow global warming.

We may already be witnessing the impact of global warming on tropical storms and flooding in the U.S. Again, that is a question difficult for science to answer definitively. There is not enough data yet. The empirical evidence says we have not seen a perceivable increase in the number or intensity of tropical storms in the Atlantic Ocean — even with Harvey, Irma and Maria included in the dataset.

However, that finding could change in a short period of time. Another year or two like 2017 in the Atlantic and the ‘no impact on tropical storms’ argument gets sent to the scientific dustbin.

On the positive side, if Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria are a precursor of the new normal, we have gained some insight on the financial risk global warming poses to the U.S. and other countries exposed to coastal flooding and hurricanes in the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico.

Puerto Rico will rebuild. The goal should be to ensure that all new construction on the island will pass rigorous building standards designed to survive Category 5 hurricanes. Puerto Rico can be the leading edge of a new urban planning philosophy for coastlines that addresses the realities of the global warming age.

The damages to residences of Texas, Florida and Puerto Rico are tragic. But they are also manageable, particularly if our governments start developing concrete plans to help people migrate from at-risk areas and to improve building and zoning codes to minimize future weather-related risks.

What we don’t need to do is crush the world economy with a crash program of getting to ‘zero net emissions’ by 2050. At this point, such a goal is a castle in the sky built by climate change alarmists that have little to risk and much to gain by scaring policy makers into potentially counter-productive government interventions in the private economy.

Don’t compound the original mistake of recklessly burning fossil fuels in serving economic growth by embarking on an equally reckless path.

The Paris Accord targets were never going to be met. Any time you get that many countries to agree on something, you know it has to be more illusion than substance. Countries were willing to sign on to the Accords because it asked of its signers very little additional sacrifice beyond what they were already doing or planning on doing.

Global warming is real. Humans caused it. And there is a warming threshold (~ 3 °C) that we must avoid. And now we must pursue a series of policies that will adapt to this reality and hopefully mitigate most of global warming’s worst consequences.

About the author: Kent Kroeger is a writer and statistical consultant with over 30 -years experience measuring and analyzing public opinion for public and private sector clients. He also spent ten years working for the U.S. Department of Defense’s Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness and the Defense Intelligence Agency. He holds a B.S. degree in Journalism/Political Science from The University of Iowa, and an M.A. in Quantitative Methods from Columbia University (New York, NY). He lives in Ewing, New Jersey with his wife and son.