By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; September 27, 2020)

What is it about Democratic congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard (D-HI) that compels her to call out her own party every time it appears hypocritical?

In the age of #MeToo, America’s homodox-class in the news media saw no contradiction in cheering the French film “Cuties” for its vivid exploration into the sexual awareness of young girls growing up in today’s over-sexualized, social-media-driven culture. Alone among her liberal and progressive colleagues, Gabbard has been the only Democrat to point out that the making of “Cuties” involved adults coaching underage girls how to simulate sexual acts on stage. Though many think the film is a powerful critique of today’s over-sexualized society and its impact on children, other thoughtful people believe the film fits the definition of child pornography.

Predictably, Gabbard was accused by some in the mainstream media of being aligned with QAnon-sourced conspiracy theories. Smears and name-calling are the go-to-move for today’s media and political elites.

So what is Gabbard’s next move? Attacking the Democratic Party’s current sacred cow: ballot harvesting.

‘What could be wrong with ballot harvesting?” you ask, particularly at a time when a worldwide pandemic makes any kind of mass, in-person activity — like voting at your local polling station — a threat to one’s health.

Isn’t ballot harvesting just a fast and efficient way to collect absentee (mail-in) ballots?

Gabbard’s answer is not what Democrats want to hear.

“Nothing is wrong with absentee or mail-in voting,” says Gabbard. But underneath the Democrats’ push for mail-in voting for this upcoming election is pressure for states to allow ballot harvesting.

What could be wrong with something sounding so wholesome that it requires harvesting? Is Gabbard against corn and Halloween pumpkins too?

Of course not. Rather, Gabbard believes ballot harvesting threatens the fundamental integrity of our democratic system because it allows for third parties to collect and deliver voter ballots to the state agencies responsible for counting votes.

Unlike in-person and absentee voting, ballot harvesting puts someone between an eligible voter and their vote.

So what is wrong with third parties being involved in the process?

Pretty much everything.

Here is Gabbard’s view on ballot harvesting and the role of third parties in the electoral process:

According to Gabbard: “The strength of our democracy lies in the integrity of our elections that every one of us has to have faith that our vote will count. But right now there are still many states in our country that allow for something called ballot harvesting. This is a system that allows for third parties to collect and deliver ballots for other people, potentially large numbers of people. Unfortunately, ballot harvesting has allowed for fraud and abuse to occur by those who could tamper with or discard ballots to try to sway an election for or against a certain candidate or party.”

Gabbard continues…

“Our vote is our voice, so whether in the midst of a pandemic, as we are now where mail-in-voting is likely to drastically increase, no one should get in between a voter in the ballot box. And while some states have prohibited

vote harvesting or ballot harvesting, many have not — which again allows for

abuse from third parties collecting and mishandling ballots. This is something that we’ve actually seen happen in recent elections.”

In response to the drive to make mail-in-voting the norm for the 2020 national election, Gabbard and Congressman Rodney Davis (R-IL), have introduced a bill in Congress (H.R.8285) that will “protect the chain of custody for every one of our ballots by prohibiting funding from going to States that allow ballot harvesting to occur.”

For the most part, Democratic Party leaders and their media surrogates have ignored Gabbard’s latest fusilade against party orthodoxy, but the fact remains serious questions remain if ballot harvesting is allowed to persist going into the current election.

Ballot harvesting goes beyond the normal absentee voting process. In 27 states and Washington, D.C., it’s legal for residents to allow a non-family member to mail in or drop off their ballot, according to policies tracked by the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Ballot harvesting and absentee voting are not the same thing, yet they are routinely confounded in the media.

Absentee voting does not put a third party between your vote and its official tally (through state-run election boards), while ballot harvesting does.

What could go wrong if the Democrats get ballot harvesting allowed across the country?

Leave it to a crooked Republican operative to provide the answer.

In 2016, a Republican operative used ballot harvesting to help turn a congressional election in favor of a Republican candidate.

A coordinated, unlawful ballot harvesting scheme operated in the 2018 general election in rural Bladen and Robeson counties in North Carolina’s 9th congressional district, most likely, changed the outcome of an election.

At a basic level, what happened in North Carolina’s 9th congressional district was as follows:

Leslie McCrae Dowless Jr., a political operative paid by Republican congressional candidate Mark Harris, paid local people $125 for every 50 mail-in ballots they collected in Bladen and Robeson counties. That means they could have been altered before being counted — which is what appears to have happened. Democrat votes were most likely illegally discarded through the ballot harvesting system.

This is what fraud looks like when performed by someone with no understanding on how to avoid looking like a fraud.

Its vote fraud by those who know how to avoid looking like frauds that I most fear.

In the end, the congressional election in North Carolina’s 9th district had to be re-competed, but the lesson was clear: ballot harvesting is prone to fraud.

Fast forward to 2020 and the question of ballot harvesting is largely dismissed by the media and academics.

“The evidence presented does not make the case that voter fraud is a major problem in America,” concludes Elaine Kamarck and Christine Stengleinfrom the Brookings Institute.

The research says all forms of voter fraud are extremely rare.

Yet, in fact, in addition to the North Carolina case, there is concrete evidence from the past that ballot harvesting has resulted in, at at a minimum, questionable activities.

“People were carrying in stacks of 100 and 200 (ballots). We had had multiple people calling to ask if these people were allowed to do this,” said Neal Kelley, the registrar for voters in Southern California’s Orange County.

Who were the “multiple people”?

Political operatives.

If you are like me, you’d trust “political operatives” with your life and the life of your children.

But do you trust them with our electoral process?

In 2016, California Gov. Jerry Brown signed AB1921, a California law which legalized ballot harvesting. Prior to that law, only a family member or someone living in the same household was permitted to drop off mail ballots for a voter. But under but the new law, anyone — including political operatives — are allowed to collect and return ballots.

What could go wrong?

Failure to deliver ballots in a timely manner is probably where ballot harvesting is most vulnerable to vote fraud.

In the 2020 primary, 70,330 mail-in ballots were rejected by California election officials during the March presidential primary because they were not postmarked on or before Election Day, according to the California Secretary of State.

Based on what we’ve seen in practice, ballot harvesting invariably includes cases where some ballots are delivered too late to be counted. But suppose this tardiness has a systematic (even if inadvertent) bias favoring one party over another? Worse yet, suppose a ballot harvester decides to slow-walk completed ballots from households perceived to be hostile to their preferred candidate or party?

As Gabbard points out, once a state puts third parties between the voter and the vote tallying process, the possibility of fraud grows considerably.

The direct manipulation of a ballot is not as likely an avenue for vote fraud, but hard to dismiss as a possibility.

More than 1,000 ballots were disqualified in Fresno County because the signature didn’t match the one on file with election officials. The same problem nixed over 1,300 ballots in San Diego County — and over 14,000 statewide. In some of those cases, voting experts say, a family member might have signed for others in the household, which is illegal.

In California (as in every other U.S. state), it is a felony for anyone to tamper with a ballot, which is why election officials check the signature on all mail-in ballots against the voter’s signature on record.

In some states allowing ballot harvesting, official ballots are mailed proactively to addresses known to have had eligible voters, but there is no guarantee the voter still lives there.

In cases where the voter has moved or doesn’t receive their mail directly, someone besides the voter could possess their official ballot.

Again, there is no existing evidence of systematic ballot fraud in such cases, but the possibility cannot be ignored, particularly if this method for delivering ballots becomes industrialized on a national scale.

Long delays in election outcomes will erode our nation’s already declining confidence in vote results.

Similar to what happened in California’s 2020 primary, in a New York congressional primary, election officials discarded thousands of ballots for lack of postmarks. The election result was not certified until six weeks after the election. Were the discarded ballots random or systematic? Don’t ask the State of New York, they’d rather not know.

Arizona’s 2018 senatorial election took weeks after Election Day to determine the outcome. And why? Apparently, Arizonans like to vote early, by mail, and that requires significantly more work for Arizona elections officials.

Arizona state law requires a mail-in ballot to be sealed and signed, and elections officials must match each signature to the one on file with the voter’s registration before even opening the envelope.

In 2018, that meant 1.7 million individual signatures that had to be confirmed by hand.

This tedious process is exacerbated in the final days of an election when mail-in ballots flood a state’s election officials, who on election day are dealing with the significant complexities of in-person voting.

Was the delay in the 2018 election indicative of an illegitimate election in Arizona? No, but did it invite multiple conspiracy theories suggesting as much? An undeniable, ‘Yes.’

And it is in that operational space where our democracy erodes with ballot harvesting.

Are there potential benefits to ballot harvesting?

Certainly, yes.

The 2018 midterm election was the first California election where the state’s Democratic party fully capitalized on ballot harvesting, which had been legalized in 2016.

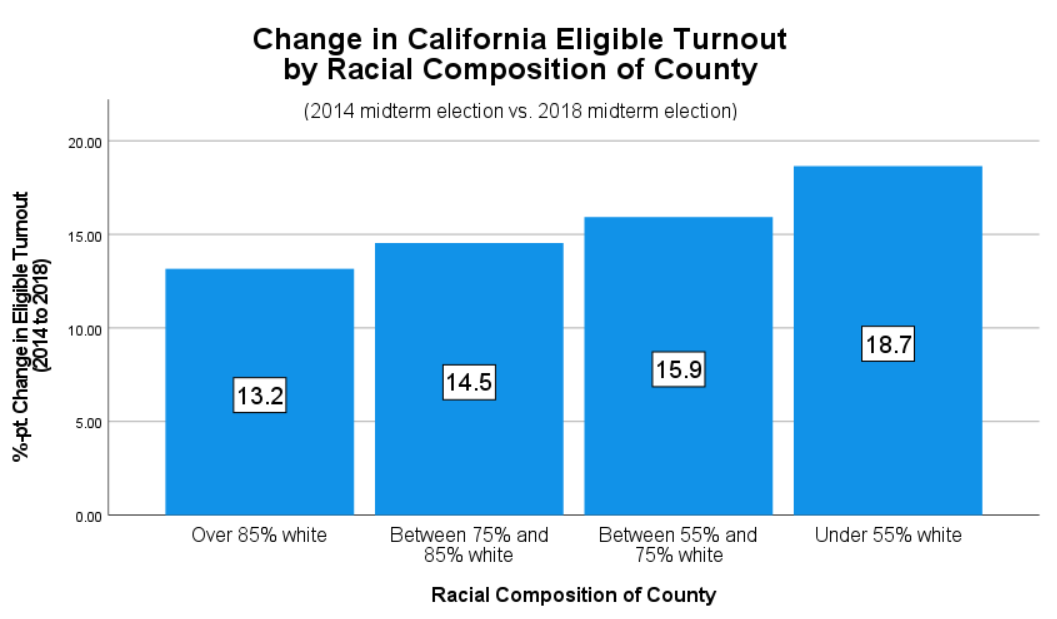

As seen in Figure 1—which shows the change in California eligible voter turnout by county racial composition (i.e., % of county population that considers themselves ‘white only,’ according to the 2010 U.S. Census) — in California counties under 55 percent white, voter turnout increased between the 2014 and 2018 midterm elections by 18.7 percentage-points, compared to only 13.2 percentage-points for counties over 85 percent white.

Figure 1: Change in California Eligible Turnout by County Racial Composition (Source: California Secretary of State)

This turnout increase cannot necessarily be attributed to ballot harvesting, as the numbers in Figure 1 are based on aggregate, county-level data. Furthermore, the turnout increases in California’s least-white counties were also a function of non-white voters being much more energized than white voters. Call it the Trump Effect if you will, but there is little argument that the Trump presidency, independent of loosened mail-in ballot procedures, drove a lot of Americans to the polls, many of whom wouldn’t have voted otherwise.

Still, according to a U.S. Census report the nationwide turnout increase for Hispanic and Black voters in 2018 was between 10.8 and 13.4 percentage-points over 2014. The significantly higher turnout increases in California’s least-white counties encourage fair speculation that ballot harvesting may have partially been responsible for those higher numbers.

The same U.S. Census report points out that non-Hispanic whites still turnout to vote at a higher rate than non-Hispanic Blacks, non-Hispanic Asians, and Hispanics (57.5%, 51.4%. 40.2%, and 40.4%, respectively).

Any improvement to our voting process that narrows racial and ethnic vote turnout gaps is a good thing. But there are better ways to increase voter turnout than ballot harvesting, which creates a security vulnerability that can’t be brushed off as a ‘conspiracy theory’ or ‘fake news.’

Journalists and political analysts at major media outlets — such as MSNBC, CNN, Slate.com and Politico.com — continue to say there is ‘zero evidence’ of vote fraud related to ballot harvesting, but that assertion is itself demonstrably false. Besides, within any system where a potential vulnerability is identified, waiting for the vulnerability to be exploited before addressing the problem is not good systems management. In fact, its a recipe for disaster.

And that is what could happen if ballot harvesting becomes a national norm for our future elections.

Tulsi is right again.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: nuqum@protonmail.com

or DM me on Twitter at: @KRobertKroeger1