(Headline graphic by Sagearbor; used under the CCA-Share Alike 4.0 International license.)

By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; October 9, 2020)

Why is it that the two major U.S. political parties (but particularly the Democrats) make little effort to attract voters who are, for various reasons, detached from the two-party system?

Loosely called the ‘political center,’ when they do get attention it is mostly from academics who divide them up into “independents,” “undecideds,” and ideological “centrists,” and generally dismiss them as less-informed and prone to emotional appeals from politicians.

Occasionally, a political campaign will spend some of its finite campaign funds on attracting “centrist” voters; but, for the most part, the modern U.S. political campaign today spends the vast majority of its money on rallying their partisans and getting them to vote.

But why so little attention to a political center that is presumably capable of changing the outcome in a tight election?

According to many in the political and media establishment, the reason is simple: There is no political center in the U.S. anymore. Eligible voters are either Democrats or Republicans, even if they don’t categorize themselves as such. And those who don’t fit neatly into the GOP vs. Democrat box are essentially irrelevant.

In October 2015, The New Yorker‘s Ryan Lizza offered this analysis: “The center is dead in American politics.”

Two years later, New York Magazine’s Eric Levitz shared a similar epiphany with readers: “The Democrats can abandon the center—because the center doesn’t exist.”

If two New York-based writers can’t convince you that the political center is irrelevant, let New York-based data guru Lee Drutman take a stab:

“Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: Independent voters will decide the election. Or better yet: Moderate voters will decide the election. Or, wait for it … If Democrats can move to the middle, they will win in 2020.

These tropes conjure up a particular image: a pivotal bloc of reasonable “independent” voters sick of the two major parties, just waiting for a centrist candidate to embrace a “moderate” policy vision. And there’s a reason this perception exits: You see just that if you look only at topline polling numbers, which show 40-plus percent of voters refusing to identify with a party, or close to 40 percent of voters calling themselves moderates.1 But topline polling numbers mask an underlying diversity of political thought that is far more complicated.

Moderate, independent and undecided voters are not the same, and none of these groups are reliably centrist. They are ideologically diverse, so there is no simple policy solution that will appeal to all of them.”

Drutman’s data-driven argument is thick with condescension and contempt for segments of U.S. society (moderates, independents and undecided voters) for which he offers one insightful observation: “None of these groups are reliably centrist.”

Drutman’s observations, however, are not novel. Political scientists have been marginalizing the political center for over 60 years, starting with the seminal work, The American Voter, and reinforced more recently by Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels in their 2016 book, Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government, in which they concluded the electorate neither understands nor particularly cares about policy, but instead are motivated by their group identities when making political choices.

“Most democratic citizens are uninterested in politics, poorly informed, and unwilling or unable to convey coherent policy preferences through ‘issue voting,'” write Achen and Bartels. “Voters, even the most informed voters, typically make choices not on the basis of policy preferences or ideology, but on the basis of who they are—their social identities.”

In summarizing Achen and Bartel’s work, journalist Noah Berlatsky concluded, “Voters’ policy choices typically demonstrate not thoughtful centrism, but galumphing ignorance and indifference.”

What is clear from the work of Drutman, Achen, Bartels and other political scientists, they have never worked in a competitive consumer environment. If a data analyst ever came to me and said, “We can’t build our customer base because our non-customers are too diverse and unpredictable,” that person would be re-assigned to accounting.

What political scientists are basically saying is that there is no policy solution to attract disengaged voters that fit their notion of what defines the political left and right.

As I will show below—and as Drutman actually finds but does not acknowledge in his own analysis–there is a large segment of the U.S. vote-eligible population with policy preferences out of alignment with elite assumptions on how someone’s policy views should relate to their self-ascribed ideology and partisanship.

For example, there are registered Democrats who are pro-gun control yet support strictly limiting immigration into the U.S; just as there are registered Republicans who are skeptical about the importance of climate change, but support increasing taxes on the wealthy. There is no stone tablet that says someone on the political left (or right) cannot be pro-life and also a strong supporter of Medicare-for-All.

Not only do people with hard to categorize opinions exist, there are a lot of them. And many of them vote—though not to the degree as strong partisans. Therefore, they may be an expensive vote to capture, but given their numbers, they may well be worth the effort.

When Drutman and his Manhattan happy hour companions dismiss the ideological inconsistencies of the political center, they are in fact describing and enforcing the artifice of a political system designed to marginalize a significant percentage of Americans.

Through their personal, day-to-day interactions with friends and family, as well as their regular diet of mainstream news, Americans have come to believe some issue positions are inherently incompatible with correct-thinking liberals or conservatives.

It’s a self-reinforcing feedback loop that serves the two major political parties and their corporate patrons very well. What better way to guarantee the American voter will only support one of the two establishment parties than to make the average American think there are only two rational choices on Election Day.

In reality, there is a significant percentage of Americans largely disconnected from the dominant narrative driving today’s political discussion about political ideology, partisanship and policy.

So why are so many in the national media so determined to convince Americans that the U.S. no longer has a political center?

Perhaps the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu offers a clue:

“If you search everywhere, yet cannot find what you are seeking, it is because what you seek is already in your possession.”

I prefer the axiom’s complement, first articulated in my recollection by Sherlock Holmes:

“You can’t find what you aren’t looking for.”

An apparent consensus of political and media elites conclude that the political center doesn’t exist in the U.S. because they simply aren’t looking for it.

When one actually looks at the data, however, a large and politically relevant political center is impossible to miss.

The Data

For the following charts, I analyzed the American National Election Studies (ANES) 2019 Pilot Study, an internet-based survey of 3.000 U.S. adults conducted by YouGov.com from December 20-31, 2018. The data for the charts below are weighted to match national characteristics on gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, geographic region, and presidential candidate choice.

This survey, now over one year old, was chosen for its public availability and the wide range of policy questions it asked respondents in the month after our last nationwide election.

The Results

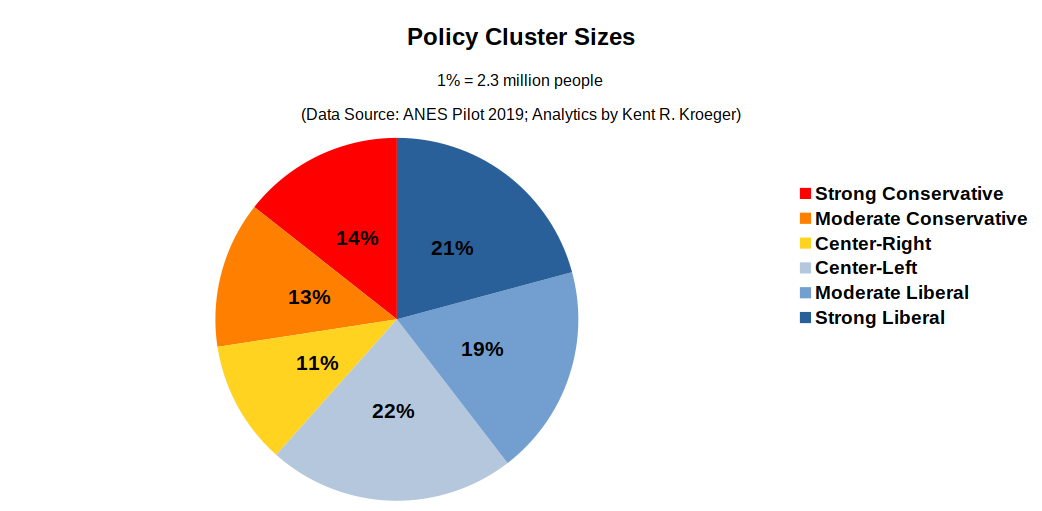

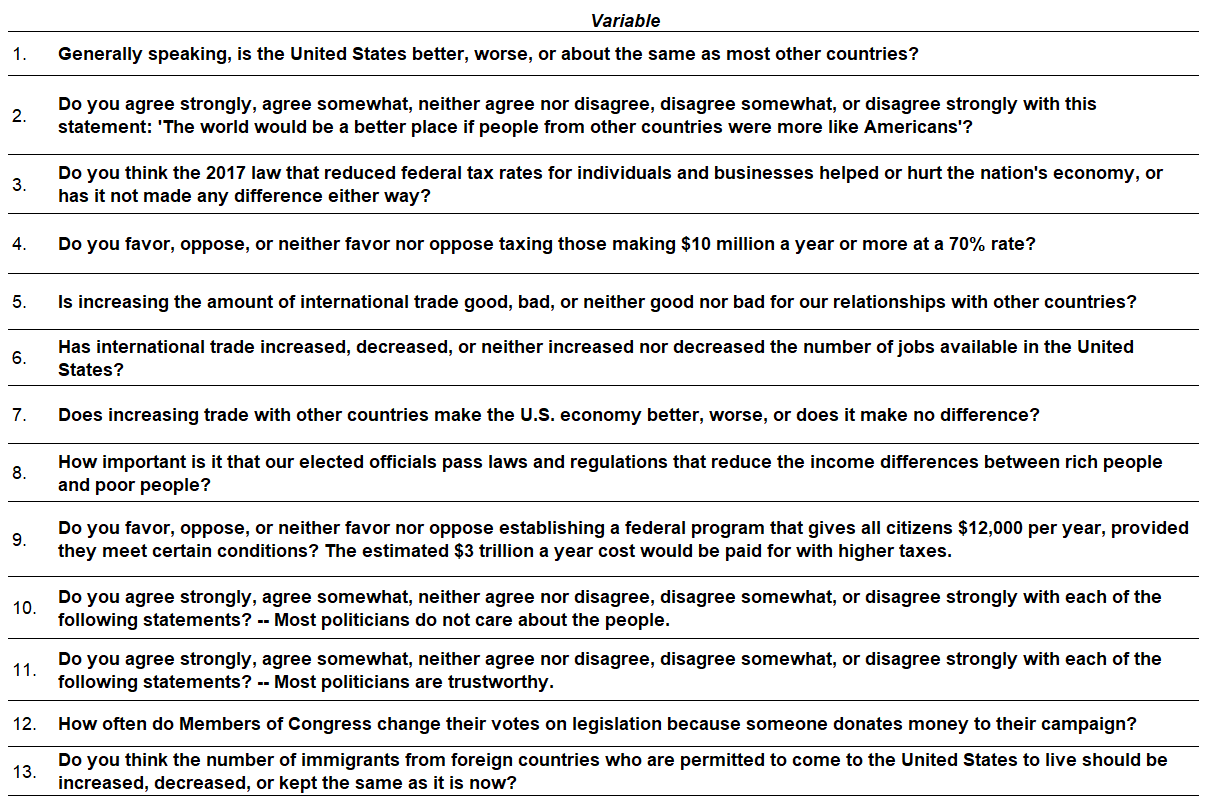

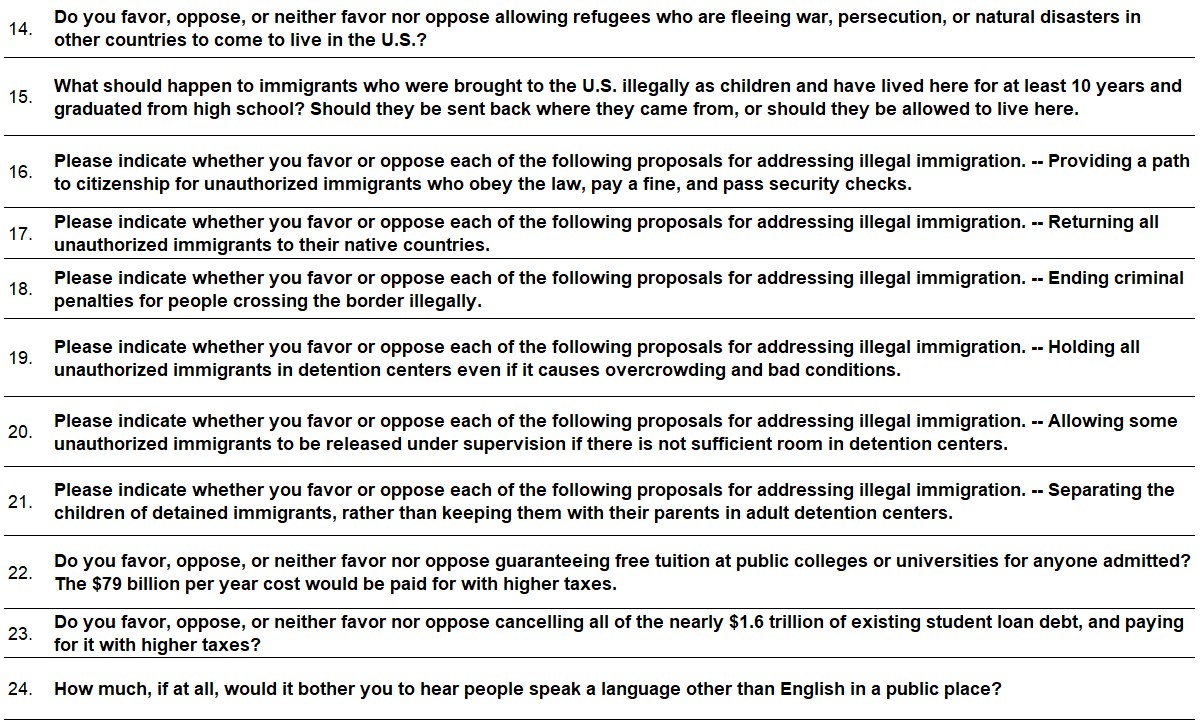

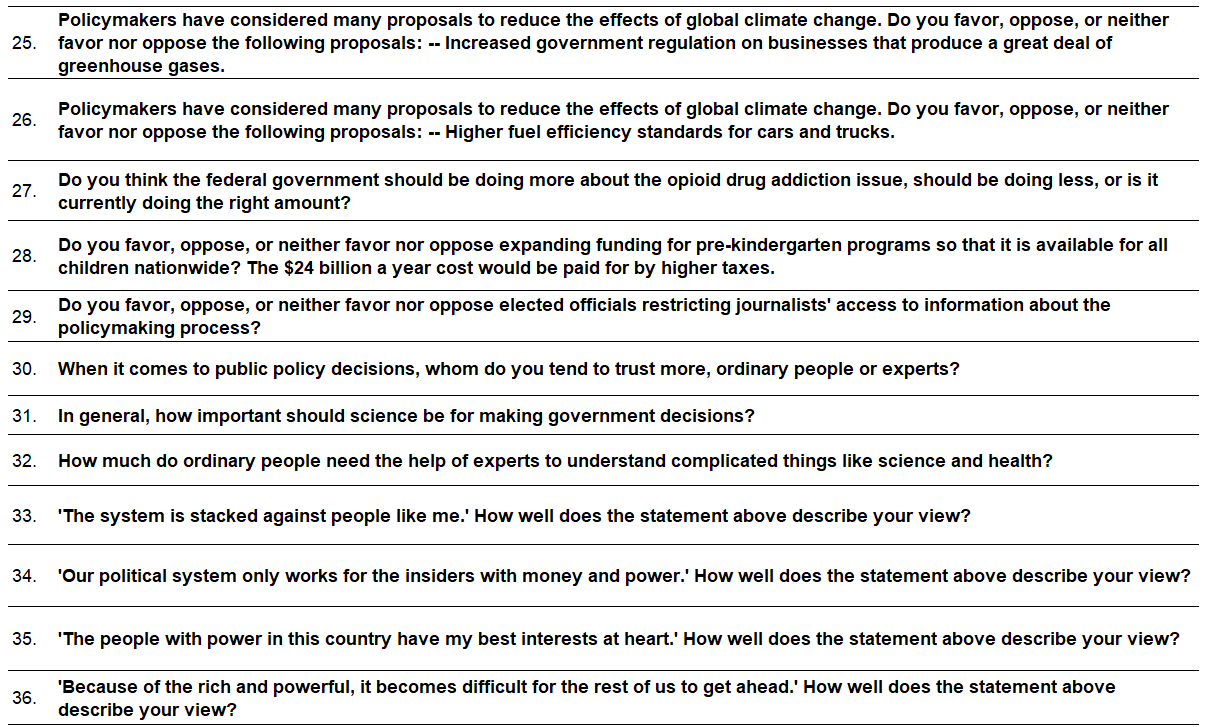

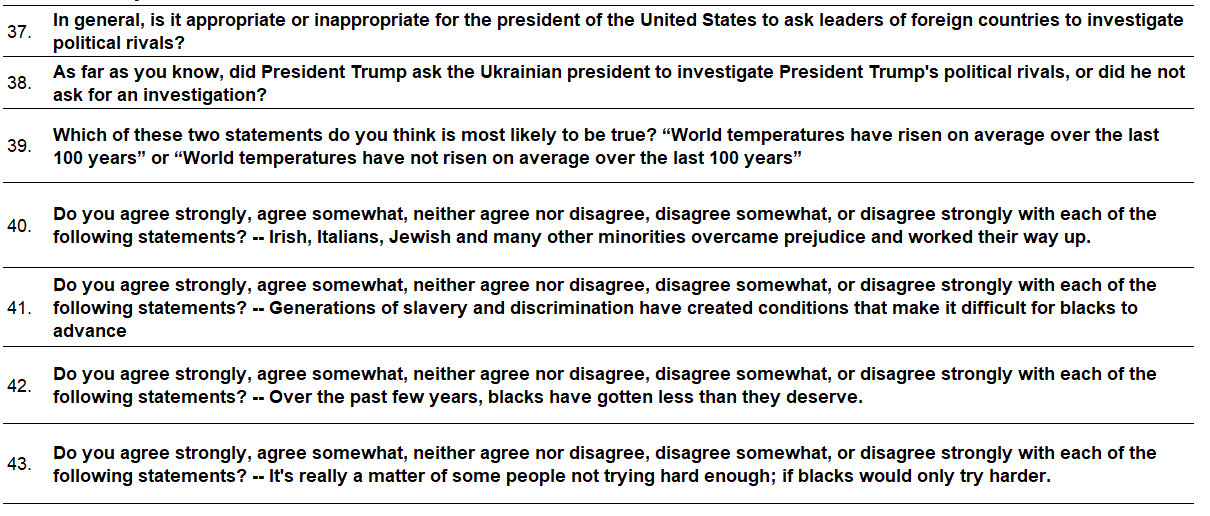

To facilitate this data presentation, I segmented the U.S. adult population into six policy clusters based on 43 attitudinal and policy-related questions in the ANES 2019 Pilot study and sorted these segments based on their relationship to respondents’ self-described ideology (see Figures 1a and 1b below). The policy clusters are as follows (from most supportive of Trump to least): Strong Conservative, Moderate Conservative, Center-Right, Center-Left, Moderate Liberal, and Strong Liberal.

The attitudinal and policy items used for the cluster analysis are listed in Appendix A below.

While my naming convention confounds the two distinct concepts of partisanship (Republican-Democrat) and ideology (Conservative-Liberal), it is important to emphasize that this attitudinal segmentation is based solely on policy attitudes and opinions.

Figure 1a: The Six Policy Clusters

Figure 1b: The Six Policy Clusters by Self-described Ideology

In December 2018, a month after the Democrats regained the U.S. House in the midterm elections, strong and moderate liberals far outnumbered strong and moderate conservatives (40 percent to 27 percent, respectively). The largest policy clusters were the Center-Left (22%, 50.6 million people) and Strong Liberal (21%. 48.3 million people) segments, and the smallest were the Strong Conservative (14%, 32.2 million people), Moderate Conservative (13%, 29.9 million people), and the Center-Right (11%, 25.3 million people).

The center of American politics may contain 76 million Americans. Even if only 40 percent vote (as in 2016), that represents about 30 million people.

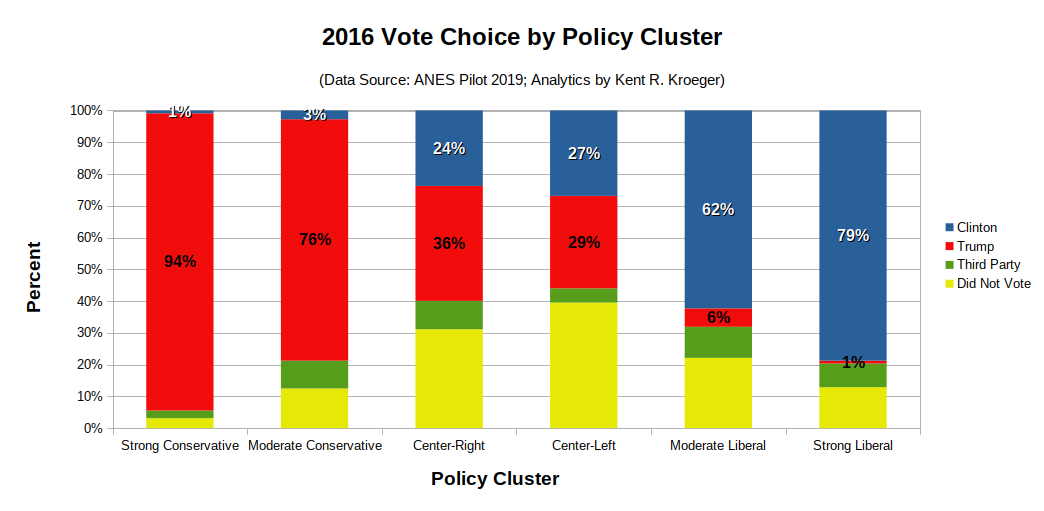

Figure 2: The Six Policy Clusters by 2016 Presidential Vote Choice

Figure 2 (above) vividly shows why Hillary Clinton lost to Donald Trump. Though her policy-related base was probably larger than Trump’s at the time, she was unable to keep their loyalty. Only 79 percent of Strong Liberals voted for Clinton compared to the 94 percent of Strong Conservatives who voted for Trump. A similar picture emerges with Moderate Liberals and Moderate Conservatives.

More interesting, perhaps, is what happened with those Americans with hard to categorize policy views (i.e., Center-Right and Center-Left). The majority of both segments voted, but while the Center-Left was evenly divided between Trump and Clinton, the Center-Right decisively preferred Trump over Clinton (36% to 24%, respectively).

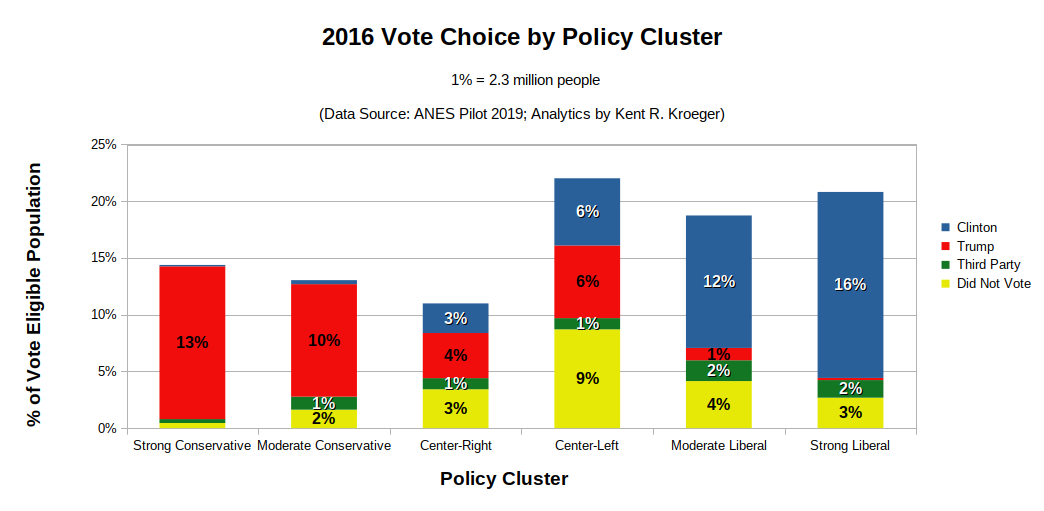

If we account for the different sizes of these six policy clusters, we can infer from Figure 3 that there were enough Trump voters among the Center-Left that had Clinton persuaded one-sixth of them to vote for her instead of Trump, she would have gained around 2 million additional votes.

Remember she lost the Electoral College by around 70,000 votes in a handful of key states (MI, PA, WI).

Figure 3: The Size of the Six Policy Clusters and their 2016 Presidential Vote Choice

While many factors in 2016 assembled to create the perfect anti-Clinton storm, a contributing ingredient was her inability, in contrast to Trump, to attract voters in the political center.

Clinton’s failure is evident in the volumes implied in Figure 3:

- Around 2 million Moderate Liberals voted for Trump.

- Around 14 million Center-Left voters voted for Trump.

- Around 4 million Moderate Liberals voted Third Party.

- Around 4 million Strong Liberals voted Third Party.

Who is in the political center?

As Drutman found, categorizing the political center is not easy. They are a motley blend of various social backgrounds and attitudes. The center is far from homogeneous. But, according to data from the ANES 2019 Pilot Study, centrists do stand out from the other policy clusters across a number of key demographic measures.

Compared to the other policy segments, the two center clusters are younger, more female, less educated, and living in lower-income households (see Appendix B below for the detailed demographic charts).

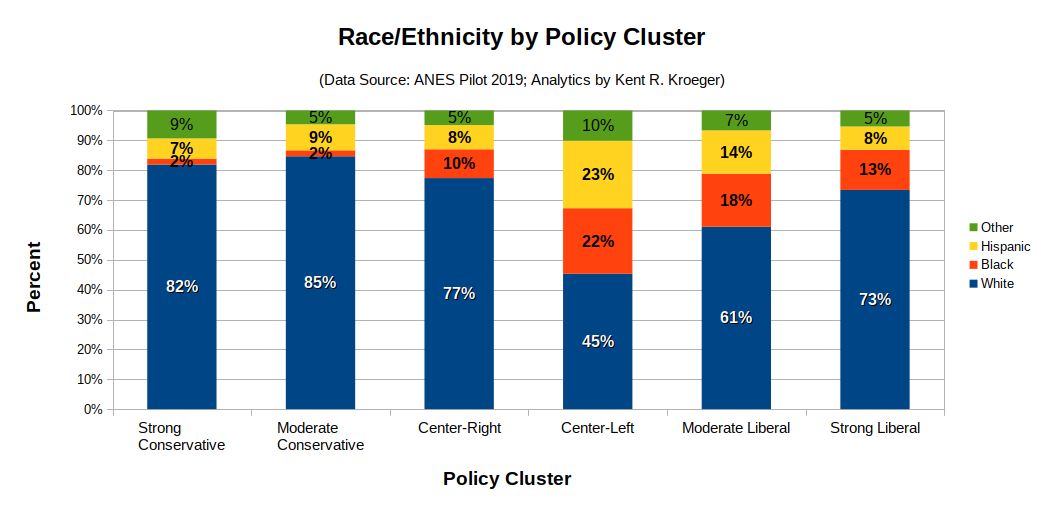

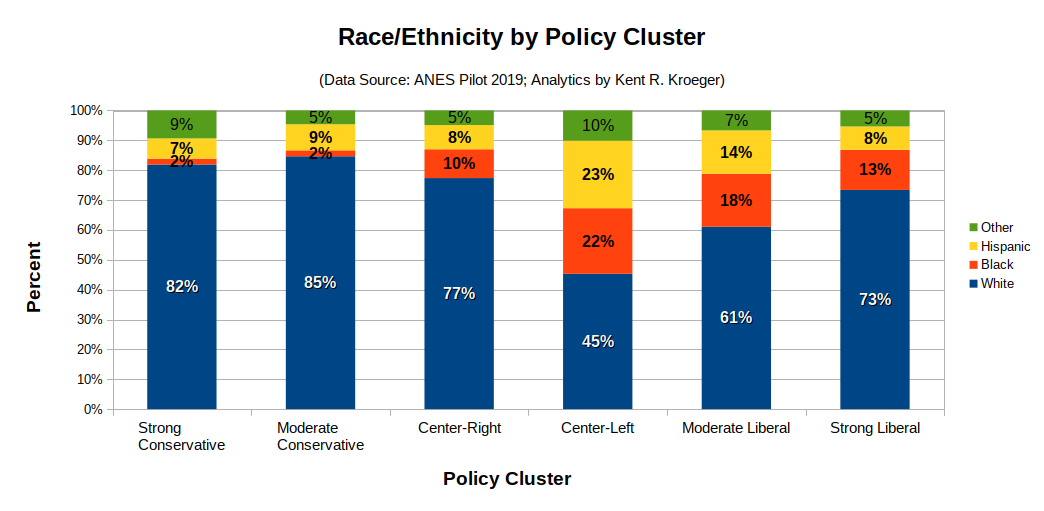

The two center clusters do, however, differ substantially from each other on race/ethnic composition (see Figure 4). Fifty-five percent of Center-Left members are non-white, compared to only 23 percent of the Center-Right.

Figure 4: The Six Policy Clusters by Race/Ethnicity

The Center-Left is racially and ethnically diverse, and the Center-Right much less so (though the Center-Right is the most diverse of the three right-of-center clusters).

Notable also is that the three left-of-center clusters are substantially more diverse in terms of race/ethnicity than the three right-of-center clusters. There should be no doubt among political operatives that the growing racial/ethnic diversity of the American population currently works in the favor of the Democratic Party. But, as I will show next, that conclusion must include a recognition that there are policy issues—should they become election drivers—that could driver Center-Right voters to the left and, vice versa, drive Center-Left voters to the right.

The Democrats have been ceding the Center to the GOP

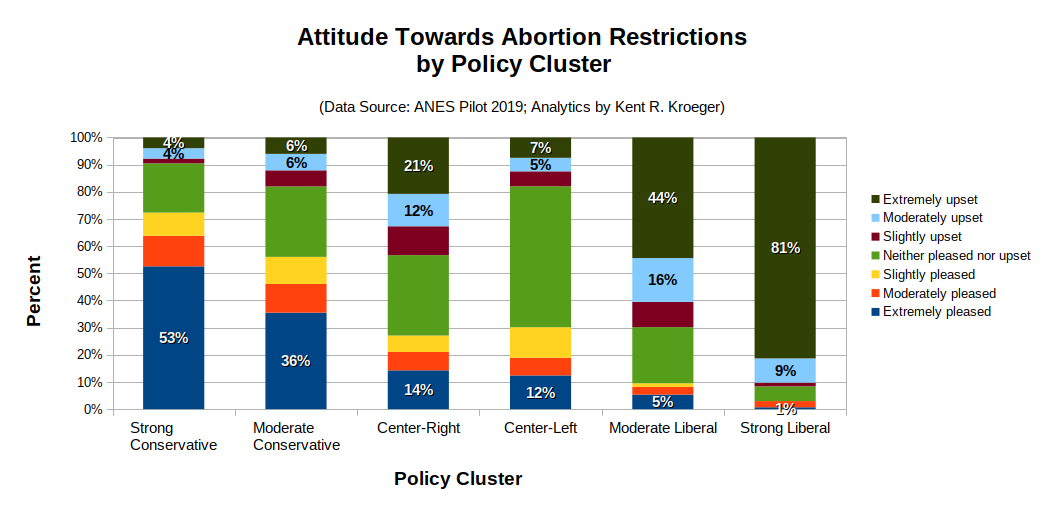

Arguably, at least since the 1990s, establishment leaders for both the Democrats and Republicans have eschewed compromise on their party’s core issues. For the Democrats, no issue is as central to the party’s ideology as abortion rights.

Prior to the 2016 campaign, Democratic Party platforms and presidential candidates had generally argued for making abortions “safe, legal, and rare.” With the 2016 and 2020 campaigns, however, the Democratic Party platform dropped that rhetorical pretense and opted, instead, for an uncompromising view of abortion rights:

“Democrats believe that every woman should be able to access high-quality reproductive health care services, including safe and legal abortion…

…Democrats oppose and will fight to overturn federal and state laws that create barriers to women’s reproductive health and rights. We will repeal the Hyde Amendment, and protect and codify Roe v. Wade.”

In practical terms, the national Democrats believe an abortion should face restrictions no greater than that for getting a tooth pulled. The national Republicans, for their part, have been consistently anti-abortion since the Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v Wade ruling.

As for the Republicans, among their ideological blind spots, no issue activates their lizard brain faster than the concept of universal, single-payer health care.

‘Socialized medicine!’ the GOP cries anytime even modest health care reform measures–such as Obamacare–are considered in Congress. Obamacare–a reform whose core idea is to unleash the IRS on Americans who refuse to buy health insurance–is to ‘socialized medicine’ what former New Jersey Governor Chris Christie is to Olympic pole vaulting.

Given how polarized party leaders are on these two issues–abortion and universal health care–it is surprising the Democrats are choosing to ignore a large number of people they may be losing at election time because they are not consistently marketing their candidates to the political center.

For example, the 2016 Clinton campaign may have lost two million potential votes for failing to appeal more aggressively to Center-Right voters on abortion rights. According to data from the ANES 2019 Pilot Study, 33 percent of Center-Right say they would be at least “moderately upset” if abortion restrictions were increased (see Figure 5). That translates to 8.3 million people in a segment where only 6.1 million voted for Clinton in 2016.

Figure 5: The Six Policy Clusters by Attitudes Towards Abortion Restrictions

The Democrats make a similar mistake with the political center on universal health care (e.g., Bernie Sanders’ Medicare-for-All proposal). Thirty-two percent (i.e., over 8 million) Center-Right Americans at least moderately support Medicare-for-All (see Figure 5). That’s a higher level of support than among Center-Left Americans.

Figure 6: The Six Policy Clusters by Attitudes Towards Medicare-for-All

But wouldn’t a Medicare-for-All appeal by the Democrats turn off some of their core supporters? Of course that is the risk–which is why persuasion still matters in American campaigns. Sometimes, to win elections, candidates need to lead their base as they try to expand their electoral coalition beyond their base.

It’s called strategic adjustment.

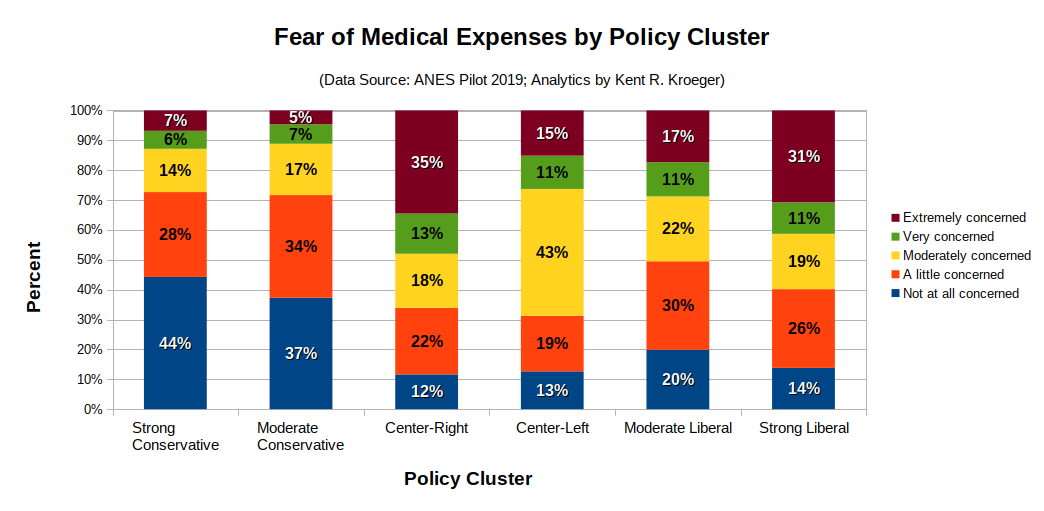

Given that health care is perennially among the most important issues to voters at election time, consider the vote potential squandered by the Democrats when they spend more time defending private health insurers and pharmaceutical companies than advocating for guaranteed, affordable universal health care. According to the ANES 2019 Pilot Study data, 48 percent of Center-Right Americans are at least “very” concerned about future medical expenses–the highest level of any of the six policy clusters (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: The Six Policy Clusters by Fear of Medical Expenses

And, conversely, the Republicans jeopardize their own electoral competitiveness when the continue to oppose universal health care proposals favored by almost half of Center-Right Americans.

Final Thoughts

Let me preface my last comments on the American political center by emphasizing what is NOT meant by “making appeals to the political center.”

Centrist voters are not necessarily attracted to centrist candidates or ideas. Quite the opposite, the research suggests they are more motivated by emotional appeals than specific policy ideas; such that, namby-pamby, wishy-washy “middle-of-the-road” rhetoric is not the optimal path for gaining centrist support.

That psychological reality, however, has not produced policy outcomes in the best interests of most voters, according to Achen and Bartels.

But their conclusion is just a sophisticated, data-driven form of ‘victim-blaming.’

Ideologically hard-to-classify Americans (“centrists”) aren’t intellectually lazy, they just have more important things to worry about than partisan politics—things like affordable health care, housing, and education, etc.

It is not surprising to me that political strategists and pundits find centrists frustrating. They don’t fit it neat little boxes, which is why Get-Out-The-Vote (GOTV) tactics are far more appealing to them than any meaningful efforts at persuasion.

Unfortunately, the fundamental mistake political strategists make when they advocate for GOTV strategies at the expense of appeals to the political center is the assumption that voters can be owned by a political party more easily than they can be persuaded.

It is a recipe for disaster, for it also assumes political parties and campaigns are static, non-strategic actors.

If the 2016 presidential campaign taught us anything, it is that parties and candidates can make substantive and abrupt strategic adjustments for a net political gain (Trump’s call in the 2016 election for renegotiating international trade agreements, closing down tax loopholes for hedge fund managers and ending America’s forever-wars are prime examples of this type of ideological flexibility). [Yes, I know Trump failed spectacularly on two of those promises, and it may cost him dearly in the 2020 election.]

The Democrats may not own the African-American or Hispanic vote going forward. Its a dangerous assumption that, while not likely to backfire in 2020, could easily do so in subsequent elections, especially if the GOP can demonstrate the level of ideological flexibility our current president did in 2016.

Ignoring the America’s political center is always a bad idea.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: nuqum@protonmail.com

or DM me on Twitter at: @KRobertKroeger1

APPENDIX A:

Attitudinal and Policy Items used for Cluster Analysis

APPENDIX B:

Demographic Characteristics of Policy Segments

It should be noted that probability-based margin of error calculations with the ANES 2019 Pilot Study are not applicable given the non-probability sampling methods used to recruit the YouGov national online panel. If YouGov’s online panel had been selected on a probability basis, the effective sample size in the ANES 2019 Pilot Study (n = 2,453) would have a margin of error of ±2 percentage points at the total sample level.

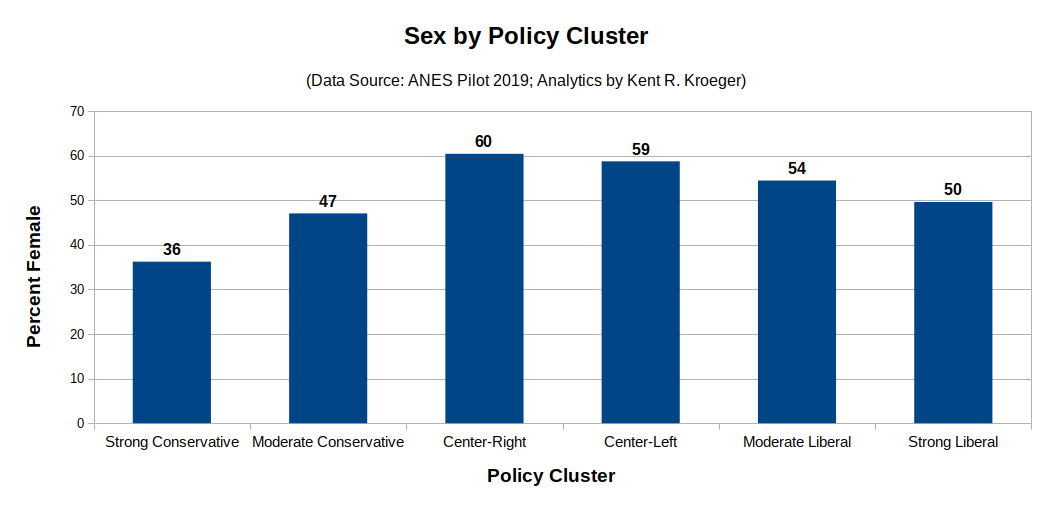

The two center policy clusters skew more female than the other policy clusters. Sixty percent of U.S. adults in the Center-Right are female, compared to just 36 percent within the Strong Conservative cluster and 47 percent within the Moderate Conservative cluster (see Figure B.1).

Figure B.1: The Six Policy Clusters by Sex

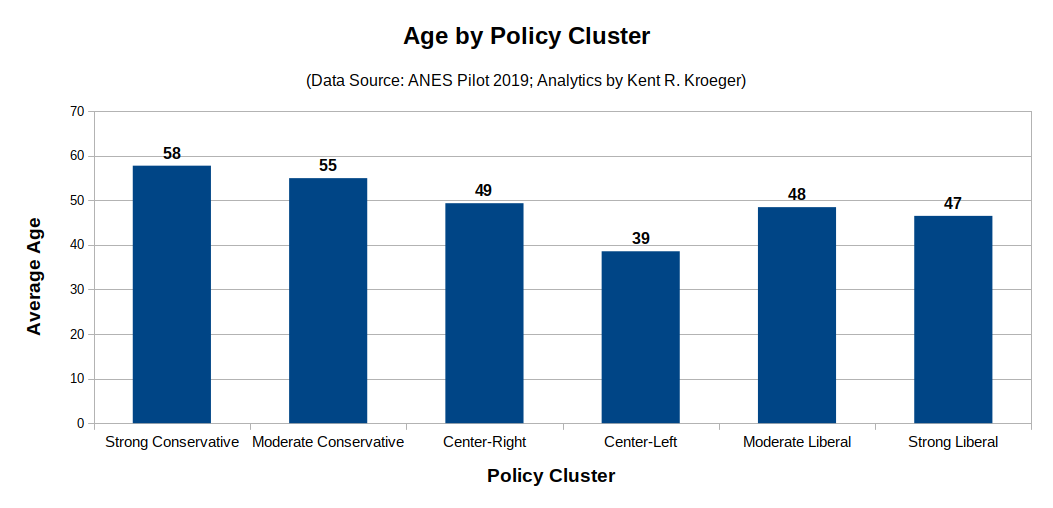

The two center clusters are more similar to the Strong and Moderate Liberal clusters in terms of average age, with members of the Center-Left being particularly young at an average age of 39 years old (see Figure B.2). Not surprisingly, the two most conservative clusters are also the oldest.

Figure B.2: The Six Policy Clusters by Age Groups

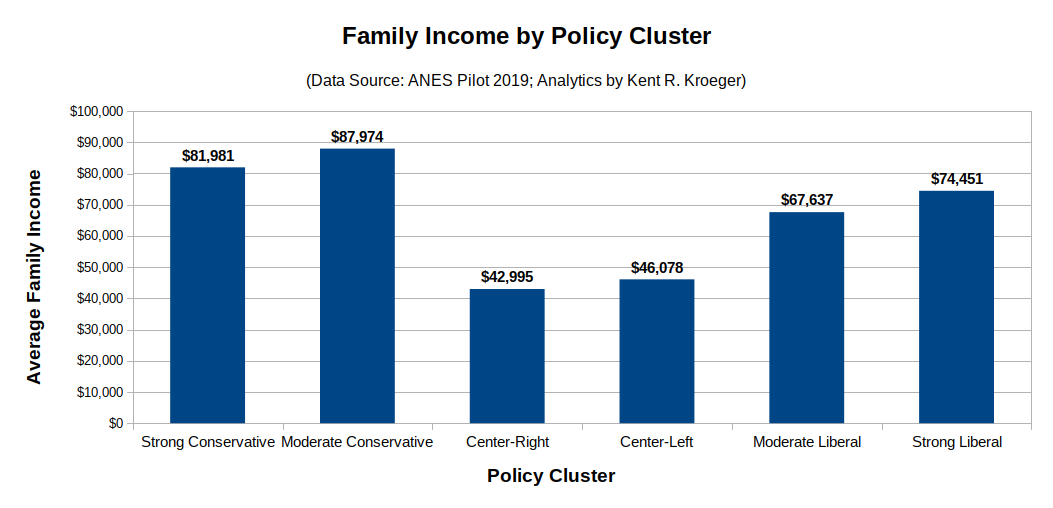

The wealthiest clusters are the Strong and Moderate Conservative clusters, both averaging over $80,000 annually for family incomes (see Figure B.3). Conversely, Center-Right and Center-Left clusters have the lowest annual family incomes ($42,995 and $46,078, respectively).

Figure B.3: The Six Policy Clusters by Annual Family Income

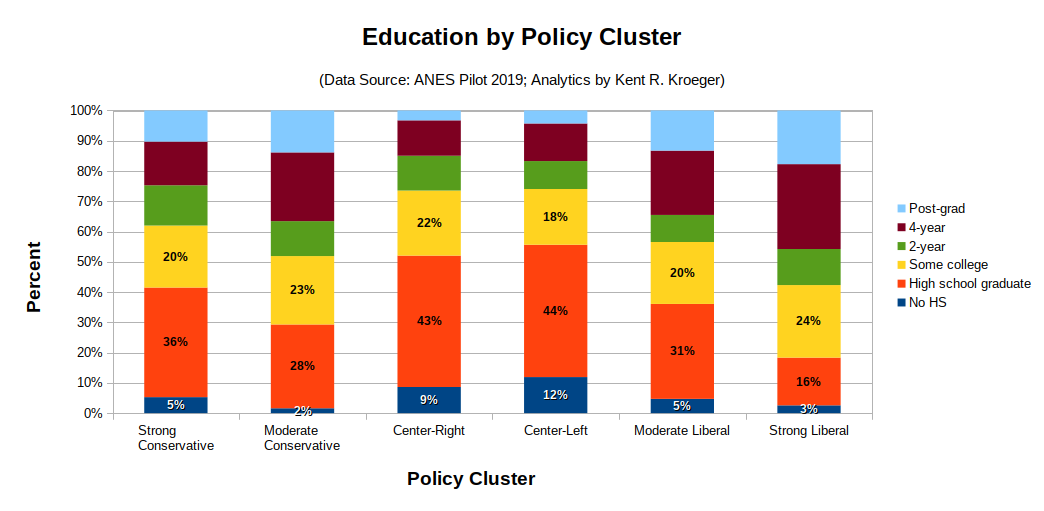

As seen in Figure B.4, the Strong Liberal cluster is more educated (45% with at least a 4-year college degree), followed by Moderate Conservatives (35%), Moderate Liberals (33%) and Strong Conservatives (24%). Less than 20 percent of members in the two center clusters have at least a 4-year college degree.

Figure B.4: The Six Policy Clusters by Education

While the two center clusters are similar in age, gender, education and income, they differ in their race/ethnicity composition (see Figure B.5). Over 50 percent of Center-Left members are non-white, compared to only 22 percent of Center-Right members. The least diverse clusters are the Strong Conservatives and Moderate Conservatives (17% and 15% non-white, respectively).

Figure B.5: The Six Policy Clusters by Race/Ethnicity Categories