[Headline graphic: St. Gertrude Catholic Church (Chicago, Illinois), April 2020 (Photo by: Paul R. Burley; Used under the CCA-Share Alike 4.0 International license.)

Data used in this article can be found on GITHUB

By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, October 14, 2020)

In August I posted an article discussing the importance of culture in modeling cross-national variation in coronavirus case and fatality rates. Its basic premise was that some cultures are more amenable to the individual-level behavioral changes (e.g., wearing masks and social distancing) needed to stunt the spread of the virus (i.e., East Asian collectivist cultures), while other cultures are more prone to spreading the virus (i.e., American individualism).

One reader suggested another culturally-based explanation for some of the cross-national variation in coronavirus cases, particularly among European nations: Catholicism.

My initial reaction was that the suggestion was plausible given that Belgium, France, Italy, Spain, and Mexico are majority-Catholic countries (see Figure 1) and were among the countries with the highest infection and deaths rates at that time.

Figure 1: Percentage of Catholics in European and other selected countries

But why would Catholic countries be more susceptible to the coronavirus? Catholicism is being confounded with more logical causal factors, I surmised. For example, Catholic-majority countries in Southern Europe are generally poorer than Northern European countries. It is also true that practicing Catholics tend to be older (a subgroup more vulnerable to the coronavirus) and have slightly larger household sizes; but, when I included country-level measures for GDP per capita, median age and average size of household in my statistical models, none came close to statistical significance.

I subsequently dismissed Catholicism as a likely factor in explaining the spread of the coronavirus, despite the prima facie evidence in its favor. [If 30 years of statistical modeling has taught me anything, don’t get too attached to seemingly plausible explanations and theories.]

However, a few days ago a former colleague sent of me a link to a 2016 study published by the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI): Race, Religion, and Political Affiliation of Americans’ Core Social Networks, by Daniel Cox, Juhem Navarro-Rivera, and Robert P. Jones, Ph.D.

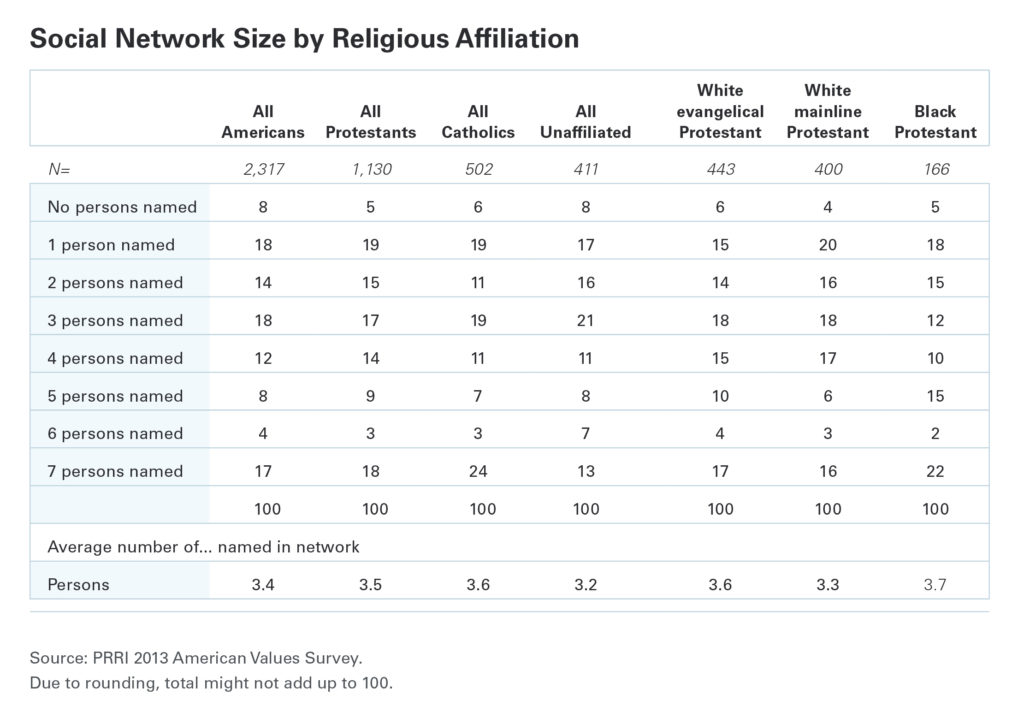

The study took an in-depth look at Americans’ closest personal relationships and found that the average American (n = 2,317) has 3.4 people in their close social network (see Figure 2), with Black protestants (n = 166) having the most (3.7 people) and the religiously unaffiliated having the least (3.2 people). Catholics (n = 502) reported 3.6 people in their close social network.

Figure 2: Social Network Sizes by Religious Affiliation (Source: PRRI)

More discriminating is the percentage of respondents with more than seven people in their close social network. Twenty-four percent of Catholics reported seven or more people in their social network, more than any other religious affiliation.

Coincidently, as I began to search for cross-national data on social network sizes (I found little), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) posted in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report a case study about a family reunion in June-July 2020 where 20 family members from five households, including one teen exposed to SARS-CoV-2 prior to the reunion, spent three weeks at a vacation retreat.

Subsequently, 11 family members contracted the coronavirus.

“There is increasing evidence that children and adolescents can efficiently transmit SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19),” says the CDC report. “This investigation provides evidence of the benefit of physical distancing as a mitigation strategy to prevent SARS-CoV-2 transmission. None of the six family members who maintained outdoor physical distance without face masks during two visits to the family gathering developed symptoms.”

While these findings aren’t surprising, it highlights a possible causal mechanism for linking cultural characteristics prevalent among Catholic families with the spread of the coronavirus.

The Data

In studying the relationship of Catholic-majority countries to the spread of the coronavirus, I controlled for other factors that should correlate with cross-national differences:

- National-level COVID-19 testing frequency per capita (Johns Hopkins University – CSSE),

- National-level suppression and mitigation (S&M) policies (Oxford’s Stringency Index), and

- Health care system quality and capacity (OECD health statistics).

I obtained data on the percentage of Catholics in 40 highly-developed countries from Catholic-Hierarchy.org (see Figure 1). For the summary measure of health care system quality I created an additive index based on three health care system components relevant to the treatment of COVID-19: (1) the number of nurses per 1,000 people, (2) the number of hospital bed per 1,000 people), and the percentage of the country’s population with medical insurance (public or private). All three health care sub-measures were converted to z-scores before creating the index score. The health care system quality index scores for each country can be seen in the Appendix (see Figure A.1).

Finally, the national-level suppression and mitigation policy daily index scores (Oxford’s Stringency Index) were averaged within each country over a period from January 20 to April 30, 2020. The intent was to assess whether stringent S&M policies early in the pandemic were effective in reducing the cumulative number of COVID-19 cases (as of October 11, 2020). The Stringency Index scores for each country can be seen in the Appendix (see Figure A.2).

The Linear Model

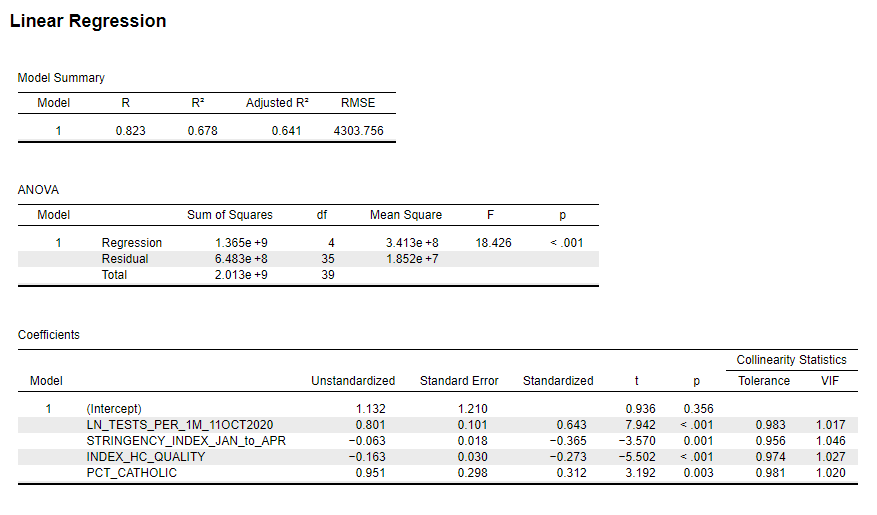

Figure 3 shows the linear model output for this four-variable model. All four variables were statistically significant and in the expected direction. National testing levels appear most strongly associated with the relative number of COVID-19 cases (i.e., more testing = more positive cases) with a standardized Beta coefficient (β) of 0.643, followed by stringency measures (β = -0.365), percentage Catholic (β = 0.312), and the health care system quality index (β = -0.273). [Given the small sample sample size (n = 40), take these differences in parameter estimates with a grain of salt.]

Overall, this simple, four-variable model explains almost two-thirds of the variance in COVID-19 cases per capita for the 40 countries in the sample.

Figure 3: Linear Model Predicting Number of COVID-19 Cases per 1M People for 40 Selected Countries (Regression model was weighted by population; Data sources: Johns Hopkins University – CSSE, Oxford University, OECD, Catholic-Hierarchy.org; Analytics by Kent R. Kroeger)

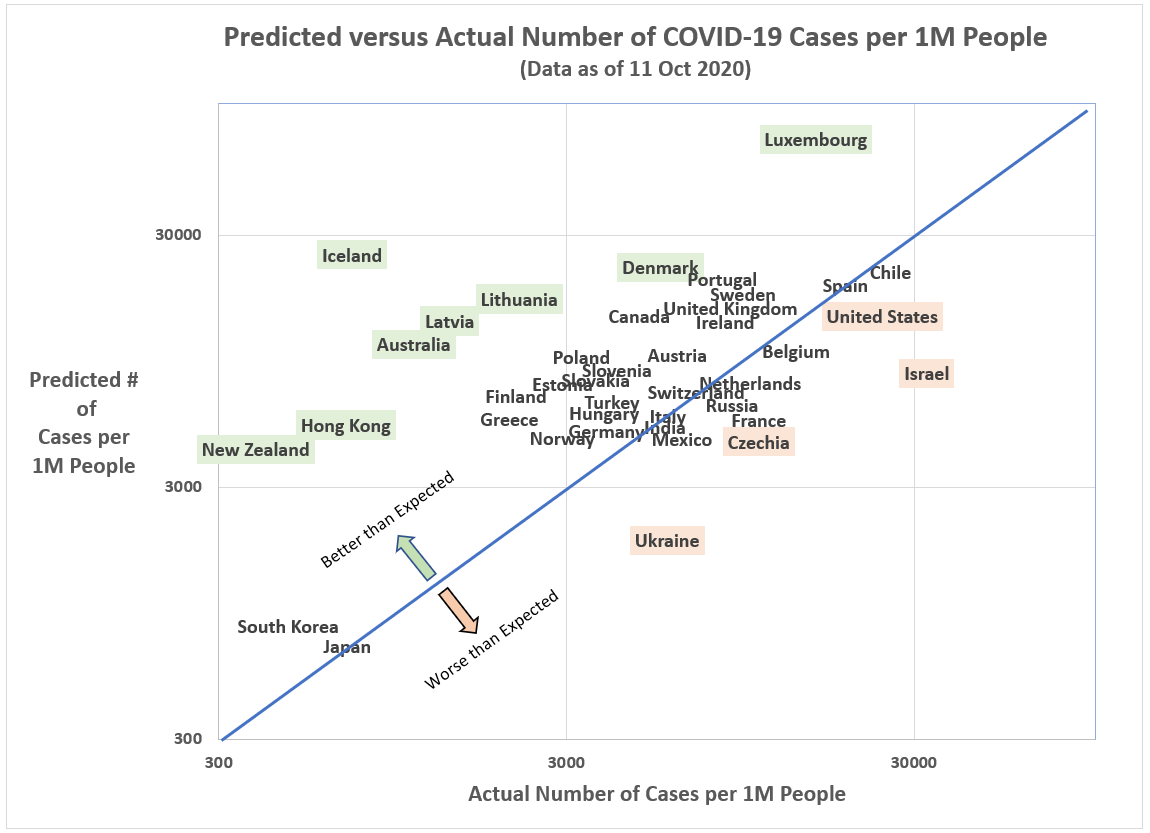

When we plot the 40 countries in our sample by their model prediction and actual values, some interesting outliers appear. Among those countries with relatively fewer COVID-19 cases per capita than predicted by the model, New Zealand, Hong Kong (not a country!), Iceland, Australia, Latvia, Lithuania, Denmark and Luxembourg stand out. Apparently, in controlling the coronavirus, it helps to either be a highly-controlled border (particularly an island) or a Baltic state.

On the not-so-good list–that is, more COVID-19 cases per capita than otherwise predicted by the model–are countries like Ukraine, Czechia, Israel and the U.S.

Figure 4: Predicted versus Actual Number of COVID-19 Cases per 1M People (Data sources: Johns Hopkins University – CSSE, Oxford University, OECD, Catholic-Hierarchy.org; Analytics by Kent R. Kroeger)

I admit that this model is too simple and static. In the real world, parameter estimates are themselves variable over time, not to mention that data quality (e.g., measurement error by a country’s statistical office) limits our ability to explain much of the nation-level variation.

Variables that once had a strong relationship in my early models of the coronavirus (namely, population density), have ceased to show statistical significance. Likewise, S&M policies that were once insignificant or significant in an unexpected direction (e.g., lockdown policies), now appear significant in the expected direction. According to this latest model, stringent suppression and mitigation measures work when they are adopted early in a pandemic.

Still, there are countries like Japan that have not enforced draconian S&M measures, yet have effectively controlled the spread of the coronavirus.

Culture matters, such that, in the cases of Japan and South Korea, whose histories include significant periods of authoritarian rule, citizens appear much more compliant with strict coronavirus measures regarding the wearing of masks and social distancing. In contrast is the United States where a significant percentage of the population puts a high premium on individualism and personal freedom.

There is no simple policy solution for this virus, but there is concrete evidence that culture is a significant factor in explaining how well nations are handling the pandemic. Culture can either work with for or against national efforts to control this virus.

In the above model, countries with a higher percentage of Catholics have, all else equal, a relatively higher level of coronavirus cases. I suspect this statistical relationship is driven by Catholicism’s generally larger, closer family networks. But I’m using aggregate data to explain nation-level outcomes. To understand what is really going within Catholic populations and the coronavirus, individual-level data is needed.

Furthermore, there is anecdotal evidence that religion affiliations other than Catholicism are significant factors in other countries with respect to the coronavirus. In Israel, a significant number of COVID-19 cases can be linked to the ultra-Orthodox Hasidic community’s participation in large-group religious activities. Similar religious activities in the U.S. have also been linked to cluster outbreaks of COVID-19, including a Houston, Texas Catholic Church which experienced a major cluster outbreak of COVID-19.

Is it large, tightly-knit social networks or large-group gatherings driving a seemingly a high incidence rate of coronavirus cases in countries with large Catholic populations?

Or perhaps singling out Catholicism altogether, as I’ve done here, is a mistake? Maybe it is something about groups of people congregating for any reason that is the true causal factor at play? [Who in the hell in Texas thought filling up Kyle Field stadium with 24,700 fans at the Texas A&M-Florida game last weekend was a good idea?]

What is irrefutable in my view is that there is no threat to humans more addressable at the individual-level than a viral pandemic.

Wash your hands. Wear a mask. And keep your distance.

How hard is that? It shouldn’t take a president (or any leader) setting a good example to inspire such simple and effective behavior by a country’s citizens. The end of this pandemic is in our own hands.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: nuqum@protonmail.com

or DM me on Twitter at: @KRobertKroeger1

APPENDIX:

Figure A.1: Health Care System Quality Index

Figure A.2: Stringency Index (Daily Avg. from January 20 to April 30, 2020)